Learning Non-Violent Social Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gamified Social Platform for Worldwide Gamers Whitepaper

Gamified Social Platform for Worldwide Gamers Whitepaper ENG Ver 2.0 Last updated July 2021 Whitepaper | Gamified Social Platform for Worldwide Gamers White Paper Ludena Protocol provides a gamified social platform for worldwide gamers The LDN token rewards users for platform engagement with fellow participants. Our 3 million strong commu- nity boasts the ultimate gamer-focused social ecosystem and offers the three major segments of the gaming industry exclusive benefits: Players Discover or upload helpful game strategies, hints and tricks and receive fair rewards for all kinds of engagement; Can easily find or sell rare and special game items in the world’s first fee-free virtual goods marketplace; Get matched with new friends to play fun and simple games with on Ludena’s 1:1 hyper casual gaming platform. Game Publishers Marketing dollars are targeted, no longer wasted, and result in real ROI effectiveness, through in-game purchases and driven player growth, due to our accumulated 1TB+ of user analytics and our 7 years of proven marketing successes. Indie Game Developers Our platform is an ideal solution for indie game developers, who want to reach a large audience, without paying exuberant commission fees, and who want to drive in-game spend, as our token economy design encourages. 1/47 ludenaprotocol.io | Copyright©2021. All rights reserved. Executive Summary | Gamified Social Platform for Worldwide Gamers Executive Summary Ludena Protocol is the first comprehensive gamified social platform, connecting gamers, from around the world, to a single application where they can play, trade and share all things gaming with one another. The Ludena Protocol team is made up of a group of professionals, who have been operating the 3 million user strong gaming social media application, 'GameTalkTalk,' for 7 years. -

Nordic Game Is a Great Way to Do This

2 Igloos inc. / Carcajou Games / Triple Boris 2 Igloos is the result of a joint venture between Carcajou Games and Triple Boris. We decided to use the complementary strengths of both studios to create the best team needed to create this project. Once a Tale reimagines the classic tale Hansel & Gretel, with a twist. As you explore the magical forest you will discover that it is inhabited by many characters from other tales as well. Using real handmade puppets and real miniature terrains which are then 3D scanned to create a palpable, fantastic world, we are making an experience that blurs the line between video game and stop motion animated film. With a great story and stunning visuals, we want to create something truly special. Having just finished our prototype this spring, we have already been finalists for the Ubisoft Indie Serie and the Eidos Innovation Program. We want to validate our concept with the European market and Nordic Game is a great way to do this. We are looking for Publishers that yearn for great stories and games that have a deeper meaning. 2Dogs Games Ltd. Destiny’s Sword is a broad-appeal Living-Narrative Graphic Adventure where every choice matters. Players lead a squad of intergalactic peacekeepers, navigating the fallout of war and life under extreme circumstances, while exploring a breath-taking and immersive world of living, breathing, hand-painted artwork. Destiny’s Sword is filled with endless choices and unlimited possibilities—we’re taking interactive storytelling to new heights with our proprietary Insight Engine AI technology. This intricate psychology simulation provides every character with a diverse personality, backstory and desires, allowing them to respond and develop in an incredibly human fashion—generating remarkable player engagement and emotional investment, while ensuring that every playthrough is unique. -

Casual Gaming

Casual gaming KW Cheng [email protected] VU Amsterdam January 28, 2011 Abstract Common elements in the design of casual games include [TRE10]: Casual games have started to get a large player - Rules and goals must be clear. base in the last decade. In this paper we are - Players need to be able to quickly reach profi- going to have a basic look at the technology in- ciency. volved in creating casual games, common game - Casual gameplay adapts to a players life and mechanics, and the influence of social media on schedule. casual games. - Game concepts borrow familiar content and themes from life. 1 Introduction 1.2 History In this paper we are going to look at how ca- sual games are being created. This will include The start of casual gaming began in 1990 when useful tools, and commonly used programming Microsoft started bundling Windows Solitaire with languages. The main part of this paper will look Windows. Many people were still getting used at some game mechanics which are at the core to the idea of using a mouse to navigate through of casual games. We will pick out some popular a graphical user interface. Microsoft used Win- games and look at which mechanics are crucial to dows Solitaire to train people to use the mouse a successful gameplay. We will also look at the and to soothe people intimidated by the operat- influence of how social media introduced more ing system. [LEV08] The reason why Windows people to casual games. Solitaire is successful is because it is accessible, you do not have to install anything, because it 1.1 What are casual games comes with your operating system. -

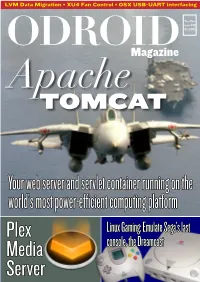

Apache TOMCAT

LVM Data Migration • XU4 Fan Control • OSX USB-UART interfacing Year Two Issue #22 Oct 2015 ODROIDMagazine Apache TOMCAT Your web server and servlet container running on the world’s most power-efficient computing platform Plex Linux Gaming: Emulate Sega’s last Media console, the Dreamcast Server What we stand for. We strive to symbolize the edge of technology, future, youth, humanity, and engineering. Our philosophy is based on Developers. And our efforts to keep close relationships with developers around the world. For that, you can always count on having the quality and sophistication that is the hallmark of our products. Simple, modern and distinctive. So you can have the best to accomplish everything you can dream of. We are now shipping the ODROID-U3 device to EU countries! Come and visit our online store to shop! Address: Max-Pollin-Straße 1 85104 Pförring Germany Telephone & Fax phone: +49 (0) 8403 / 920-920 email: [email protected] Our ODROID products can be found at http://bit.ly/1tXPXwe EDITORIAL his month, we feature two extremely useful servers that run very well on the ODROID platform: Apache Tom- Tcat and Plex Media Server. Apache Tomcat is an open- source web server and servlet container that provides a “pure Java” HTTP web server environment for Java code to run in. It allows you to write complex web applications in Java without needing to learn a specific server language such as .NET or PHP. Plex Media Server organizes your vid- eo, music, and photo collections and streams them to all of your screens. -

Dual-Forward-Focus

Scroll Back The Theory and Practice of Cameras in Side-Scrollers Itay Keren Untame [email protected] @itayke Scrolling Big World, Small Screen Scrolling: Neural Background Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Thalamus Relay sensory signals to the cerebral cortex (e.g. vision, motor) Amygdala Emotional reactions of fear and anxiety, memory regulation and conditioning "fight-or-flight" regulation Familiar visual patterns as well as pattern changes may cause anxiety unless regulated Vestibular System Balance, Spatial Orientation Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Natural image stabilizer Conflicting sensory signals (Visual vs. Vestibular) may lead to discomfort and nausea* * much worse in 3D (especially VR), but still effective in 2D Scrolling with Attention, Interaction and Comfort Attention: Use the camera to provide sufficient game info and feedback Interaction: Make background changes predictable, tightly bound to controls Comfort: Ease and contextualize background changes Attention The Elements of Scrolling Interaction Comfort Scrolling Nostalgia Rally-X © 1980 Namco Scramble © 1981 Jump Bug © 1981 Defender © 1981 Konami Hoei/Coreland (Alpha Denshi) Williams Electronics Vanguard -

Art Worlds for Art Games Edited

Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Vol 7(11): 41-60 http://loading.gamestudies.ca An Art World for Artgames Felan Parker York University [email protected] Abstract Drawing together the insights of game studies, aesthetics, and the sociology of art, this article examines the legitimation of ‘artgames’ as a category of indie games with particularly high cultural and artistic status. Passage (PC, Mac, Linux, iOS, 2007) serves as a case study, demonstrating how a diverse range of factors and processes, including a conducive ‘opportunity space’, changes in independent game production, distribution, and reception, and the emergence of a critical discourse, collectively produce an assemblage or ‘art world’ (Baumann, 2007a; 2007b) that constitutes artgames as legitimate art. Author Keywords Artgames; legitimation; art world; indie games; critical discourse; authorship; Passage; Rohrer Introduction The seemingly meteoric rise to widespread recognition of ‘indie’ digital games in recent years is the product of a much longer process made up of many diverse elements. It is generally accepted as a given that indie games now play an important role in the industry and culture of digital games, but just over a decade ago there was no such category in popular discourse – independent game production went by other names (freeware, shareware, amateur, bedroom) and took place in insular, autonomous communities of practice focused on particular game-creation tools or genres, with their own distribution networks, audiences, and systems of evaluation, only occasionally connected with a larger marketplace. Even five years ago, the idea of indie games was still burgeoning and becoming stable, and it is the historical moment around 2007 that I will address in this article. -

10 Bad Ass Games DONG 3

(Oldest to Newest) DONG 1: Top 6 Scariest The Cell: http://www.gameshed.com/Adventure-Games/The-Cell/play.html The House Horror: http://www.gamezhero.com/online-games/adventure-games/thehouse-horror.html exmortis: http://www.gameson.com.br/Jogos-Online/Terror/Exmortis.html Purgatorium: http://www.gameson.com.br/Jogos-Online/Terror/Purgatorium.html Bright in the Screen: http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view/469443 Closure: http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view/480006 DONG 2: 10 Bad ass games Dress-up Elf: http://www.badassflashgames.com/flash-arcade-game.php?gameid=34455&gamena... Mechanical Commando: http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view/475495 Fish like a man: http://www.i-am-bored.com/bored_link.cfm?link_id=55253 Zombie Tower Defense:http://666games.net/Violent/Flash/Play/620/Zombie_Tower_Defense_3.html Zombie Bites: http://www.hairygames.com/play-zombie-bites.html Zombie Golf Riot: http://www.addictinggames.com/zombiegolfriot.html Penguinz: http://www.kongregate.com/games/LongAnimals/penguinz Curious Weltling: http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view/390151 Tactical Assassin Substratum: http://armorgames.com/play/2500/tactical-assassin-substratum Gangsta Bean: http://www.addictinggames.com/gangstabean.html Kill Kar II: Revenge: http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view/519830 DONG 3: Make Harry and Herimone kiss and other online games Harry and Hermione: http://www.buzzfeed.com/ashleybaccam/harry-potter-kiss-game-battle Kill the pop-ups: http://www2.b3ta.com/realistic-internet-simulator/ I Don't Even Know: http://www.i-am-bored.com/bored_link.cfm?link_id=32676 -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle -

Game Developer Magazine

>> INSIDE: 2007 AUSTIN GDC SHOW PROGRAM SEPTEMBER 2007 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SAVE EARLY, SAVE OFTEN >>THE WILL TO FIGHT >>EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW MAKING SAVE SYSTEMS FOR CHANGING GAME STATES HARVEY SMITH ON PLAYERS, NOT DESIGNERS IN PANDEMIC’S SABOTEUR POLITICS IN GAMES POSTMORTEM: PUZZLEINFINITE INTERACTIVE’S QUEST DISPLAY UNTIL OCTOBER 11, 2007 Using Autodeskodesk® HumanIK® middle-middle- Autodesk® ware, Ubisoftoft MotionBuilder™ grounded ththee software enabled assassin inn his In Assassin’s Creed, th the assassin to 12 centuryy boots Ubisoft used and his run-time-time ® ® fl uidly jump Autodesk 3ds Max environment.nt. software to create from rooftops to a hero character so cobblestone real you can almost streets with ease. feel the coarseness of his tunic. HOW UBISOFT GAVE AN ASSASSIN HIS SOUL. autodesk.com/Games IImmagge cocouru tteesyy of Ubiisofft Autodesk, MotionBuilder, HumanIK and 3ds Max are registered trademarks of Autodesk, Inc., in the USA and/or other countries. All other brand names, product names, or trademarks belong to their respective holders. © 2007 Autodesk, Inc. All rights reserved. []CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2007 VOLUME 14, NUMBER 8 FEATURES 7 SAVING THE DAY: SAVE SYSTEMS IN GAMES Games are designed by designers, naturally, but they’re not designed for designers. Save systems that intentionally limit the pick up and drop enjoyment of a game unnecessarily mar the player’s experience. This case study of save systems sheds some light on what could be done better. By David Sirlin 13 SABOTEUR: THE WILL TO FIGHT 7 Pandemic’s upcoming title SABOTEUR uses dynamic color changes—from vibrant and full, to black and white film noir—to indicate the state of allied resistance in-game. -

Super Fish Quest: a Video Game

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-2-2012 Super Fish Quest: A Video Game Melissa Wiener Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Software Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Wiener, Melissa, "Super Fish Quest: A Video Game" (2012). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 87. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/87 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Super Fish Quest: A Video Game By Melissa Ann Wiener An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Scot Morse, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2012 Super Fish Quest 2 of 47 Abstract Video game design isn't just coding and random number generators. It is a complex process involving art, music, writing, programming, and caffeine, that should be approached holistically. The entire process can be intimidating to the uninitiated programmer, which is why I've written an all-inclusive guide to game design. With the creation of my own original video game, Super Fish Quest, as a model, I analyze each part of the design process, discuss the technical side of programming, and research how to raise money and publish a game as an independent game developer. -

The Revolutionary Potential of Independent Video Games

THE REVOLUTIONARY POTENTIAL OF INDEPENDENT VIDEO GAMES Delaney McCallum Art, Literature, and Contemporary European Thought Professors Isabelle Alfandary, Marc Crépon, and Michael Loriaux 10 December 2019 1 Introduction The definition of ‘video games’ has been hotly debated and contested since their creation - in this way, they are no different from any other human art form. In his book The Art of Video Games, media scholar Grant Tevinor characterizes video games as “interactive fictions.”1 There are two facets of this definition which require specific understanding. First, the word ‘interactive:’ this means that the audience or player of a video game communicates with a fictive scenario, whether it be a narrative or a form of physical simulation. This could take the form of clicking through web pages with a computer mouse. It could also mean performing a series of actions by pressing buttons on a controller in a certain order. In video games, some sort of transaction or communion with the player and the environment of the game takes place. The second crucial point of this definition is the word ‘fictions.’ Although this word is often used interchangeably with the word ‘narrative’ in modern game literature, there is an important distinction between the two that must be clarified. ‘Fictions’ as a category may include narratives, but this includes other constructions, from flight simulators to the landscapes created with virtual reality technology. For the purposes of this paper, I will be utilizing Tevinor’s definition of video games when I refer to specific examples and the medium as a whole. Another crucial contextualization of ensuing analysis is the interpretation of the difference between what is deemed ‘mainstream’ video games and ‘independent’ video games. -

Cave Story Ost Gravity

Cave story ost gravity click here to download Cave Story has a variety of interesting music (in org format) that was developed by Pixel through a program called OrgMaker. Pixel included a program called. Stream Cave Story 3D OST - Gravity by generallee21 from desktop or your mobile device. Cave Story Complete OST (Remastered). Top 10 Cave Story Music: Original, Remastered, New. Cave Gravity - Cave Story 3D Music Extended. Eyes Of. Download Link: www.doorway.ru?yngobyb72nc3r04 www.doorway.ru? c9f2zkq7a0w0f2p The Extended Version of Gravity. I DO NOT OWN THIS SONG, . DeceasedCrab, who did a Let's Play of Cave Story, says "Anyone who doesn't love the challenge in Cave Story+, with this song as the background music. the new version of Egg Corridor · Balrog's Theme · and Gravity with the drum track. Free Cave Story soundtracks, Cave Story MP3 downloads. Browse our great selection of Cave Story music. Unlimitted free downloads of your. Cave Story Tabs. Instrument. - Any -, Banjo, Bass Song Title sort icon · Game/ Anime · Tabber Gravity Guitar, Cave Story · Maximillian. Hero's End Guitar . md5sum: b3f1beed4ef7a7ce9cedccb. www.doorway.ru music/computer/microsoft/windows/www.doorway.ru Cave Story OST (Vinyl, LP, Album, Unofficial Release, Stereo) album Doukutsu Monogatari – Cave Story OST. Label: A3, Gravity, out Cave Story (Piano Selections) by Game Soundtrack Cat on Amazon Music. Cave Story Theme (Piano Version) Gravity (Cave Story) [Piano Version]. This music pack contains four variants of the Cave Story OST: Organya (Original) Gravity (Boss fight theme #1) peepee lol. Cemetery. Cave Story (Theme Song) Alpha Mix Plantation Version Steam Version, Alpha Mix, Plantation Gravity: Boss Battle (GBA) - The Spongebob Squarepants Movie.