Use of Simulators in Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSCASTLE BLOWHOLE No 60 Winter 2007 £1

BOSCASTLE BLOWHOLE No 60 Winter 2007 £1 photo Val Gill Basil and Jean Jose celebrate their Golden Wedding CONTENTS INCLUDE: Church & Chapel page 12 Pickwick Papers page 18 Post Office page 25 Useful Numbers page 35 Pete’s Peeps page 38 Martin’s Sporting Briefs page 42 Editorial Living in Boscastle over the noise of machinery and fed on the rebuilding of the south uncovered additional last few months has not up with the associated dust river bank [and] the final problems which have taken been without its difficulties &/or mud. tidying up across the whole time to overcome but the and inconvenience and The current forecast is that: area will be completed. streetscape work has proceeded in parallel...’ the next few months look ‘...all work should be ‘The Gateway Building like being equally chaotic. completed in the car park by is still forecast to be complete Hopefully by the next The seemingly never- 26 February [then] Carillion by mid January and…it Blowhole things will look ending regeneration works [will] relocate to a much is anticipated that work much better and life will continue apace (or not, as smaller establishment...close will continue through the start to return to normal it occasionally appears) and to the Gateway Building... Christmas period and may after three and a half difficult I am sure that most of us are Most reconstruction will be include some weekend years. working. heartily sick of the sight of completed before Easter and Wishing everyone a Merry heavy plant, hard hats and the last work scheduled will ‘The road closure continues Christmas and all good reflective jackets,������������tired of the be in the harbour and focussed ...Excavation of the trenchline wishes for a 2008 PA Boscastle Blowhole Team The editorial team reserves the right to edit, accept, or reject any material submitted for publication in the Blowhole. -

NNAS Lecture 1St February in the Town Close Auditorium, Norwich Castle Museum

NNAS Lecture 1st February in the Town Close Auditorium, Norwich Castle Museum. Dr Richard Maguire, Senior Lecturer in Public History, School of History, University of East Anglia, on the Cold War Anglia project. Once again the projection equipment let us down so Richard had to begin his lecture without illustrations but gallant efforts by Sophie Cabot eventually enabled the pictures to be shown. His theme was the culture of the Cold War and he gave a brief outline of the early UK weapons programme to combat the threat from Soviet Union bombers and to launch retaliatory attacks. He chose four locations to illustrate its effects on the landscape of East Anglia. (a) RAF Bawburgh nr. Norwich (b) RAF Feltwell (c) RAF Barnham nr. Thetford (d) RAF Orford Ness in Suffolk All of these were highly classified in their time, which means accurate details about them are still sketchy. Bawburgh This was a virgin site. pristine farmland, before it became part of a radar defence network, imposed by Government without being integrated into the local community. It altered centuries of agricultural use and the surrounding landscape. Whereas Bawburgh pre-WWII was in the middle of nowhere now it is adjacent to the A47 and filled in with development. The original station was part of the 1950s Rotor Radar System to modernise the United Kingdom’s radar defences. At one time 40 airforce personnel worked there but little is left except an underground bunker with a bungalow built over the top (a similar example exists at Trimmingham). The main guardhouse bungalow. Feltwell The airfield was part of a network built in the late 1930s with a curved array of hangers, similar in layout to many of the other RAF airfields of the period (for example RAF Marham, RAF Watton and RAF West Raynham). -

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

Types of Aircraft That Used RAF Church Fenton During 2012 and 2013

Air Command Secretariat Spitfire Block Headquarters Air Command Royal Air Force High Wycombe Ministry Buckinghamshire ' HP14 4UE of Defence Ref. 2015/07992 2 October 2015 Dear Thank you for your e-mail of 29 August 2015 asking for information about aircraft using RAF Church Fenton during 2012 and 2013. You requested the following information: "In relation to the information provided on the number of flights from the airfield I would be grateful if you could provide details on the types of aircraft that came in and out of the airfield. If you can provide this information I would be grateful if you could confirm if you are happy for this information to be released to a third party." I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. We have completed a search of our paper and electronic records for the information you have requested an.d I can confirm that information within the scope of your request is held. Please find attached at Annex· A, broken down by year, _a list of the different aircraft types that used RAF Church Fenton during 2012 and 2013. The list contains both military and civilian aircraft that used the station. You should note that in 2012 our records indicate that a glider and tug aircraft used RAF Church Fenton on a single day in 2012. However, the records do not indicate the type of the glider or tug aircraft. The Ministry of Defence is content for you pass on to a third party both the attached information and previous details of aircraft movements provided to you by the Flight Operations Manager at RAF Linton-on-Ouse. -

RAF Centre of Aviation Medicine Noise and Vibration Division

RAF Centre of Aviation Medicine Noise and Vibration Division RAF Henlow Bedfordshire SG16 6DN Tel:RAF 01462 851515 Ext 6051 Mil: 95381 6051 Fax: 01462 857657 Mil: 95381 Ext 6051 Email: [email protected] DSEA-CPA-Policy 1a Date: 15 MAY 2013 REPORT NUMBER: OEM/22/13 A REVIEW OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL NOISE IMPACT OF RAF CHURCH FENTON. Author: Max Glencross, Noise and Vibration Division, RAF CAM, RAF Henlow. References: A. RAFCAM Tasking Proforma file reference 0409100903. B. RAFCAM NVD Report OEM/17/01. C. Wimpey Report No: ER0325/07 dated Aug 89. INTRODUCTION 1. The Noise and Vibration Division (NVD) of the RAF Centre of Aviation Medicine (CAM) were tasked at Reference A by DSEA-CPA-Policy 1a to conduct a Noise Amelioration Scheme (Military) review of RAF Church Fenton. 2. A Noise Insulation Grant Scheme (NIGS) review of RAF Church Fenton was conducted in 2001 (Reference B). The most recent Environmental Noise Contours of RAF Church Fenton were produced in Feb 1989 (Reference C). The 2001 review found that the number of movements since 1989 had decreased and the conclusion was the 1989 contours were still relevant. 3. The survey conducted in 1989 included the Percival Jet Provost turbojet which was stationed at RAF Church Fenton in a training role for fast jet, multi-engine and rotary-wing aircraft pilots. In Apr 1992 the station closed and therefore the NIGS was suspended, but the airfield remained open as a relief landing ground for the Tucano turboprop aircraft operating from RAF Linton-on-Ouse. The Tucano replaced the Jet Provost. -

Robin Hood and Doncaster Sheffield Feasibility and Options Report

ATC Services Ltd. DONCASTER PIR Robin Hood and Doncaster Sheffield Feasibility and Options Report All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Liverpool John Lennon Airport. © 2015 Liverpool John Lennon Airport Doncaster PIR Page 1 of 46 Owner: TSM 3rd February 2015 ATC Services Ltd. DONCASTER PIR Executive Summary Robin Hood Airport Doncaster Sheffield (RHADS) is a regional airport that developed from a former Royal Air Force (RAF) base known as RAF Finningley. The first commercial flight at the Airport was in 2005. In 2006, RHADS submitted an application for controlled airspace (CAS) in order to provide protection to the commercial air transport (CAT) flights operating in and out of the airport, and to connect the airport to the adjacent airways structure. The Airport lies in a unique position virtually surrounded on all four sides by small Light and General Aviation (LA and GA) airfields. This made routing CAT under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), nominally under a Deconfliction Service (DS), extremely challenging. In 2008, the CAA approved Class D CAS for RHADS, which provided a Control Zone (CTR) and associated Terminal Control Areas (CTAs). The Airspace Change Proposal attracted objections from a variety of stakeholders, each staking a legitimate claim to continue to operate without the restrictions and control measures that CAS brings. The majority of those who objected removed their objection following further consultation with RHADS and the development of formal agreements. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

Draft Statement of Common Ground Doncaster Local Plan

Draft Statement of Common Ground Doncaster Local Plan Peel L&P, Doncaster Sheffield Airport Limited & Doncaster Council November 2020 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Strategic Policy 7 3. Doncaster Local Plan 13 4. Matters of Agreement 15 5. Matters of non-agreement 17 Signed: ……………………………………………………. Dated: …3rd November 2020…………………………… David Diggle, Planning Director, Turley On behalf of Peel L&P, Doncaster Sheffield Airport Limited (DSAL) Signed: …………………………………………………….. Dated: …4th November 2020…………………………… Scott Cardwell – Assistant Director for Development On behalf of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council David Diggle [email protected] Client Turley Our reference PEEM3116 3rd November 2020 1. Introduction 1.1 This Statement of Common Ground (SoCG) is between Peel L&P, Doncaster Sheffield Airport Limited (DSAL) and Doncaster Council (hereafter referred to collectively as “the parties”) and relates to the examination of the Doncaster Local Plan. The SoCG has been developed jointly by the parties. Overview 1.2 Doncaster Sheffield Airport (DSA) is located approximately 9km south east of Doncaster town centre and lies in close proximity to the settlements of Auckley – Hayfield Green. It is also closely related to Finningley to the east and Rossington to the west, which connects to DSA via the Great Yorkshire Way (GYW). The site is entirely within the administrative boundary of Doncaster Council. 1.3 Doncaster is located at the heart of the UK’s major motorway network, with connectivity to the A1, M1, M62 and Humber ports via the M18 and M180. DSA is directly connected to the M18 by the Great Yorkshire Way link road. The recent completion of GYW phase 2 has delivered a transformative improvement in access between the airport and the wider city region, resulting in an increased catchment of 5.53 million people1. -

The Cable November 2017

1993 - 2017 IUSS / CAESAR The Cable Official Newsletter of the IUSS CAESAR Alumni Association Alumni Association NOVEMBER 2017 ONE LAST DIRECTOR’S CORNER WARM GREETINGS TO ALL IUSS ALUMNI! Jim Donovan, CAPT, USN (Ret) Becky Badders, LCDR, USN (Ret) What an incredible “System” of Navy professionals and patriots I have come to be associated with over these past 45 years. And to Please allow me as your new Alumni think, we’re still organized and contributing! I have Association Director to introduce myself. I am been honored to be Director of the IUSS CAESAR Lieutenant Commander Rebecca “Becky (Harper)” Alumni Association for the past 10 years when I Badders, United States Navy (Retired), and I spent relieved Ed Dalrymple who held the post since its 1984 through 1997 as an IUSS Officer. Beginning inception for an amazing 15 years. Ed, you’re still with my Midshipman Cruise on USS John Rodgers my hero! DD 983 in CIC, I was fascinated by IUSS!! After I was commissioned, I served on temporary duty at But like all good things this too must come to an NOPF Dam Neck in the summer of 1984, attended end. It’s time for me to move on to allow someone FLEASWTRACEN in Norfolk, OWO training at else, someone with fresh ideas and experiences the Readiness Training Facility at Centerville Beach, opportunity to take over the helm of the IUSSCAA. CA (As part of the last officer class to pass through We have found that individual in LCDR Becky those illustrious doors) and then served my first Badders, USN (Ret). -

Design & Access Statement

Design & Access Statement Proposed Vulcan Hanger, Doncaster Sheffield Airport, Doncaster July 2017 Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson Revision History Rev. Date Initials Details * 31.07.2017 Initial Issue A 16.08.2017 Minor Updates Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson 2 s:\architecture\2016-247\reports\16247-a-pl_design and access statement.docx Scheme Information Scheme: Proposed Vulcan Hanger, Doncaster Sheffield Airport, Doncaster Applicant: RG Group Proposed Use: Vulcan Hanger Site Area: 0.8 hectares (8022m2) Introduction The site is located to the east of Hayfield Lane adjacent to the existing boundary of Doncaster Sheffield Airport (DSA). This application is submitted for full detailed planning approval. Site and Surroundings The site for the proposed hanger is adjacent to the boundary of DSA and is a site that was formerly within the airport boundary when it was RAF Finningley. The site contains an aircraft maintenance / refuelling stand that was historically used by the Vulcan Bombers. The site is located to the north of DSA and has a direct existing taxi way to the runway of DSA, which will allow the Vulcan access to the airport area. The site is accessed from Hayfield Lane with a short internal access road leading to the site. Located to the north of the site is a Water Facility and a Railway line, the east and south is DSA and to the west are further parts of the adjacent Water Facility and open fields, beyond those are commercial and residential properties. Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson 3 Apart from the existing aircraft stand, the site is grassed with the expecting of an existing Interceptor tank, which is being retained in the scheme. -

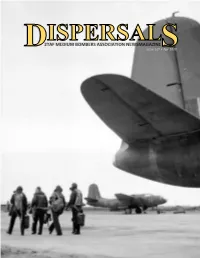

Dispersal 04/2020

1 2nd TACTICAL AIR FORCE MEDIUM BOMBERS ASSOCIATION Incorporating 88, 98, 107, 180, 226, 305, 320, & 342 Squadrons 137 & 139 Wings, 2 Group RAF MBA Canada Executive Chairman/Editor David Poissant 1980 Imperial Way, #402, Burlington, ON L7L 0E7 Telephone: 416-575-0184 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary/Treasurer Susan MacKenzie #2 - 14 Doon Drive, London, ON N5X 3P1 Telephone: 519-312-8300 E-mail: [email protected] Western Representative Lynda Lougheed PO Box 54 Spruce View, AB T0M 1V0 Telephone: 403-728-2333 E-mail: [email protected] Eastern Representative Darrell Bing 75 Baroness Close, Hammond Plains, NS B4B 0B4 Telephone: 902-463-7419 E-mail: [email protected] MBA United Kingdom Executive Secretary/Archivist Russell Legross 15 Holland Park Dr, Hedworth Estate, Jarrow, Tyne & Wear NE32 4LL Telephone: 0191 4569840 E-mail: [email protected] Treasurer Frank Perriam 3a Farm Way, Worcester Park, Surrey KT4 8RU Telephone: 07587 366371 E-mail: [email protected] Registrar John D. McDonald 35 Mansted Gardens, Romford, Essex RM6 4ED Telephone: 07778405022 Newsletter Editor Contact Sectretary (Russell Legross) MBA Executive - Australia Secretary Tricia Williams PO Box 304, Brighton 3186, Australia Telephone: +61 422 581 028 E-mail: [email protected] DISPERSALS is published three times per year. On our cover: The last crew to return from the last operational mission undertaken by No. 88 Squadron RAF prior to its disbandment, walk away from their Douglas Boston Mark IV, BZ405 'RH-E', at B50/Vitry-en-Artois, France. The crew are, (left to right); F/O J L Weston from Buenos Aires, F/O H Poole from Ilford, Essex, F/O B W Lawrence from Enfield, Middlesex, and F/S D Hack from Clevedon, Somerset.