Thoughts on Reading Radical Hope by Jonathan Lear by Alice Loyd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMAHDUS Vipu

ROMAHDUS ViPu Lokakuu 2014 1 Sisällys Lukijalle……………………………………………………… 2 1 Mikä romahdus?…………………………………………… 2 2 Romahduksen lajeista……………………………………… 6 3 Romahduksen vaiheista…………………………………… 15 4 Teoreetikkoja ja näkemyksiä……………………………… 17 5 Romahdus—maailmanloppu, apokalypsi, kriisi, utopia… 25 6 Romahdus ja selviytyminen………………………………. 29 7 Pitääkö romahdusta jouduttaa?…………………………… 44 8 Romahdus, tieto ja hallinta………………………………… 49 9 Romahdus ja politiikka…………………………………….. 53 2 Lukijalle Tämä teksti on osa pohdiskelua, jonka tarkoituksena on luoda pohjaa Vihreän Puolueen poliittiselle toiminnalle. Tekstin aiheena on jo monin paikoin ja tavoin alkanut teollisten sivilisaatioiden ja modernismin kehityskertomuksen romahdus. Tekstin ensimmäiset 8 lukua käsittelevät erilaisia teorioita, käsityksiä ja vapaampaankin ajatuksenlentoon nojaavia näkökulmia romahdukseen. Ne eivät siis missään nimessä edusta ViPun poliittisia käsityksiä tai tavotteita, vaan pohjustavat alustavia poliittisia johtopäätöksiä, jotka esitetään luvussa 9. Toisin sanoen luvut 1-8 pyörittelevät aihetta suuntaan ja toiseen ja luku 9 esittää välitilinpäätöksen, jonka on edelleen tarkoitus tarkentua ja elää tilanteen mukaan. Tätä romahdus-osiota on myös tarkoitus lukea muiden ViPun teoreettisten tekstien kanssa, niiden ristivalotuksessa. 1 Mikä romahdus? Motto: "Yhden maailman loppu on toisen maailman alku, yhden maailmanloppu on toisen maailmanalku." Moton sanaleikin tarkoitus on huomauttaa, että vaikka yhteiskunnan romahdus onkin yksilön ja ryhmän näkökulmasta vääjäämätön tapahtuma, johon -

Drumbeat: December 1, 2006

The Oil Drum | DrumBeat: December 1, 2006 http://www.theoildrum.com/story/2006/12/1/8307/71623 DrumBeat: December 1, 2006 Posted by threadbot on December 1, 2006 - 9:30am Topic: Miscellaneous [Update by Leanan on 12/01/06 at 2:10 PM EDT] House to vote on offshore drilling bill WASHINGTON - House Republicans agreed Friday to move a compromise offshore drilling bill passed by the Senate this summer that would open new territory in the Gulf Coast area to oil rigs and create a cash cow for nearby states. With time running out on the party's majority rule, GOP leaders decided to send the measure to the floor for a vote next week, Kevin Madden, a spokesman for Majority Leader John Boehner said. Energy industry: Give us something solid - Utility execs see carbon restrictions as inevitable, want regulations 'soon rather than later;' seek stability in oil markets; questions linger over nuclear power. Saudi Arabia was held up as a model example. John Roberts, an energy security specialist with Platts, the provider of energy information that sponsored the event, said the kingdom pledged $53 billion to expand its oil infrastructure. "They are putting their money where their mouth is," said Roberts. "They say they are increasing capacity, and there is no reason to think they won't. With other countries, it's much less clear." Stirling Newberry on the economy, peak oil, and global warming: The Other Future It isn't energy per se that is the problem, but the problem of recycling petrodollars and the marginal profits of energy. -

Michael: Welcome to This Episode of the Future Is Calling Us to Greatness

Michael: Welcome to this episode of The Future is Calling Us to Greatness. Today I’ll be talking with John Michael Greer, who is a peak oil writer, a blogger, actually, to be quite honest, of everyone that I’m interviewing in this series, I’ve not read anyone more deeply and more enthusiastically than John Michael. In face, my first introduction to him was just maybe eight months ago. I read The Ecotechnic Future. Richard Heinberg was the one that introduced me to that book. Then I listened to it. Fortunately it was available on audio. Then I’ve read several others of his books that I’ll talk about here. But John Michael, welcome to this podcast series, this interview series, on The Future is Calling Us to Greatness. John: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be on. Michael: So John Michael, could you begin just by sharing with our viewers and listeners a little bit about your own background, your accomplishments, and especially what you’re particularly passionate about or interested in at this time. John: Well, I reached adulthood at the end of the 1970’s, the early 1980’s, at the last time that American society was showing any signs of paying attention to the future or any future outside of Ronald Reagan’s distorted imaginations. I was at that time very heavily involved in what we used to call the appropriate tech movement. There’s a phrase that doesn’t get a lot of reference these days, but doing things like solar energy and wind power, but not taking over vast amounts of Nevada. -

Sustainability Leaders

new society publishers 2020 YEARS Sustainability Leaders Publishing Books for a World of Change 40 Years new society publishers is proud to be celebrating 40 years of activist, solutions-oriented publishing. From our roots in non-violent of Publishing civil disobedience training during the Vietnam war to today, with over for a World 500 books published — some across a dozen languages — we continue to bring positive solutions and cutting-edge ideas, to some of the most of Change troubling challenges of our time. Having never wavered from our mission to help build a just and ecologically sustainable society — placing planet and people before profit —we are proud to hold the highest environmental and social standards of any publisher in North America. With a dedicated community of changemakers and thought leaders, always working ahead of the curve, we look forward to another 40 years of bringing our readers books for a world of change. As the climate crisis accelerates and the coronavirus outbreak exposes the fragility of the just-in-time globalized, growth economy, we are focussed ever more on local resilience. Our Fall 2020 list is packed with practical books to get you started on building local capacity with how-to books on ecological land design, regenerative agriculture, and growing quality, nutritious local food – the very backbone of a resilient local economy. Yet resiliency is not all about food. We also offer tools for the deep inner work of personal transformation and methods for leveraging behavior change to build an inclusive society in which all voices are heard and all people can contribute. -

ICT After Fossil Fuels

Communications Information Technology After Fossil Fuels Wednesday, August 17, 2016 Speakers: Casey Hall directs Citizen's Engagement Lab's Climate Lab), Dr. Douglas RusHkoff, (author of THrowing Rocks at the Google Bus), RicHard HeinBerg (Post CarBon Institute), AsHer Miller (Post CarBon Institute) Contact Us: [email protected] Tweet Us: #renewablefuture WeBsite: OurRenewableFuture.org Monica Hello! ZacH An excellent, useful read! leslie [email protected] david An exciting topic, that is for sure! leslie #renewablefuture Lovis WHat is the role of B incorporation in creating the renewable/sustainable future? Jack THanks for opening this view of the Human predicament leslie CHeck out all the free reading and the in depth analysis AsHer mentioned Here: leslie www.ricHardHeinBerg.com leslie Http://www.rusHkoff.com/ leslie Http://engagementlab.org/people/casey-Harrell ZacH Your thougHts on How alternatives to the growth douBling down can enter the political reality would "Appropriate tecHnology reminds us that Before we cHoose our tools and tecHniques, we must first cHoose our dreams and values, for some tecHnologies serve them wHile others make them Craig unoBtainable" Tom Bender Looking Back it seems the only collective dreams and values centers on Silvia Can capitalism Be reformed to Be compatiBle with a living, livable planet? Can we Have a "well- Monica Can people de reformed to think in terms that are compatiBle with ecological Health, social respect ZacH You can. People can. Ben Capitalism to serve the planet... it's a Both/and. Mark THis is really Boring. WHat's the purpose Here? Economics Has Become the language of extinction as we give value to the very things that directly Craig undermine our and future generations well Being. -

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New

Advance Praise for The End of Growth Heinberg draws in the big three drivers of inevitable crisis—resource constraints, environmental impacts, and financial system overload—and explains why they are not individual challenges but one integrated system- ic problem. By time you finish this book, you will have come to two conclusions. First, we are not facing a re- cession—this is the end of economic growth. Second, this is not our children’s problem—it is ours. It’s time to get ready, and reading this book is the place to start. — PAUL GILDING, author, The Great Disruption, Former head of Greenpeace International Richard has rung the bell on the limits to growth. This is real. The consequences for economics, finance, and our way of life in the decades ahead will be greater than the consequences of the industrial revolution were for our recent ancestors. Our coming shift from quantity of con- sumption to quality of life is the great challenge of our generation—frightening at times, but ultimately freeing. — JOHN FULLERTON, President and Founder, Capital Institute Why have mainstream economists ignored environ- mental limits for so long? If Heinberg is right, they will 3/567 have a lot of explaining to do. The end of conventional economic growth would be a shattering turn of events—but the book makes a persuasive case that this is indeed what we are seeing. — LESTER BROWN, Founder, Earth Policy Institute and author, World on the Edge Heinberg shows how peak oil, peak water, peak food, etc. lead not only to the end of growth, and also to the beginning of a new era of progress without growth. -

The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-Peak World John Michael Greer

The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-Peak World John Michael Greer Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-Peak World John Michael Greer The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-Peak World John Michael Greer “[John Michael] Greer’s work is nothing short of brilliant. He has the multidisciplinary smarts to deeply understand our human dilemma as we stand on the verge of the inevitable collapse of industrialism. And he wields uncommon writing skills, making his diagnosis and prescription entertaining, illuminating, and practically informative. Not to be missed.”—Richard Heinberg, Senior Fellow, Post Carbon Institute and author of Peak Everything “There is a great deal of conventional wisdom about our collective ecological crisis out there in books. The enormous virtue of John Michael Greer’s work is that his wisdom is never conventional, but profound and imaginative. There’s no one who makes me think harder, and The Ecotechnic Future pushes Greer’s vision, and our thought processes in important directions.” —Sharon Astyk, farmer, blogger, and author of Depletion and Abundance and A Nation of Farmers “In The Ecotechnic Future, John Michael Greer dispels our fantasies of a tidy, controlled transition from industrial society to a post-industrial milieu. The process will be ragged and rugged and will not invariably constitute an evolutionary leap for the human species. It will, however, offer myriad opportunities to create a society that bolsters complex technology which at the same -

Trilithon E Journal of Scholarship and the Arts of the Ancient Order of Druids in America

Trilithon e Journal of Scholarship and the Arts of the Ancient Order of Druids in America Volume VI Winter Solstice, 2019 Copyright 2019 by the Ancient Order of Druids in America, Indiana, Pennsylvania. (www.aoda.org) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. ISBN-13: 978-1-7343456-0-5 Colophon Cover art by Dana O’Driscoll Designed by Robert Pacitti using Adobe® InDesign.® Contents Editor’s Introduction....................................................................................................I Letter from the New Grand Archdruid: Into the Future of AODA............................1 Dana O’Driscoll Urban Druidry: e Cauldron of the City..................................................................6 Erin Rose Conner Interconnected and Interdependent: e Transformative Power of Books on the Druid Path...........................................................................................................14 Kathleen Opon A Just City.................................................................................................................24 Gordon S. Cooper e City and the Druid.............................................................................................28 Moine -

Lessons from a Recent Home Retrofit

Implementing Plan C – conservation, curtailment and cooperation NewSolutionsNovember-December 2008 Number 15 Saving Energy the “Passive Way” – Lessons from a Recent Home Retrofit By Megan Quinn Bachman for reducing home energy use do not at Murphy and his wife Faith approach the 80 – 90 percent reduc- P Morgan of Community Solu- tion targets of the Passive Houses, tions knew a little about retrofitting nor do they even approach the efforts buildings for low-energy use when made during the 1970s energy crisis. they decided to turn their small 100- So-called “green building” and year-old carriage house into an artist’s energy efficiency programs for new homes like the U.S. Green Build- studio and apartment. ing Council’s Leadership in Energy After they learned how the new and Environmental Design (LEED) German “Passive House” concept can certification and the U.S. ENERGY reduce energy consumption in exist- STAR qualified homes only save, on ing buildings by up to 80 percent, average, about 25 – 30 percent of they decided to find out – and share the energy used in a typical building, with others – how much energy they according to Community Solutions. could save in their 1,000-square foot, Linda Wigington, a manager at two-story building, once used by Affordable Comfort, Inc., another horses and buggies. The Carriage House near completion (Photos: Faith Morgan) organization promoting deep energy “A Passive House is a very well- retrofits, said, “Recently much of insulated, virtually air-tight building the emphasis for low energy homes that is primarily heated by passive in the US has focused on expensive solar gain and by internal gains from mechanical and renewable systems, people [and] electrical equipment,” such as geothermal heat pumps and according to Katrin Klingenberg of solar photovoltaic arrays without the Urbana, Illinois-based Passive substantially reducing the energy load House Institute U.S. -

Transcript (PDF)

Michael: Richard, thank you so much for accepting my invitation to participate in this conversation series The Future is Calling Us to Greatness. Richard: Great. Happy to be talking with you. Michael: I knew that I wanted you to be part of this. I’ve been a fan of your work for a decade now, as you know. When I first read Powerdown I think was my first introduction. Have since read I think four of five of your books. Most recently actually I was thrilled to find that The End of Growth, actually you introduced me to another person who’s become a major person in my life in terms of intellectual ideas and that sort of thing, John Michael Greer. Richard: Great, yes. Michael: You recommended him in The End of Growth and I listen to audio books a lot. Then I checked him out and I’ve read a half a dozen of his books. I had a wonderful conversation with him in this series as well. Richard: Terrific, that’s great. Michael: Thank you for that. Let me just overview what we’re doing here. I specifically wanted to have conversations with people like yourself who get the big picture, who get the challenges coming down the pike and who are helping people to not just prepare for it in the negative sense but see the possibility that is inherent in this, what a postcarbon economy, what a 1 postcarbon world for example would look like, how to stay inspired to be in action in the face of huge challenges and that sort of thing. -

Pangaia #48 1 BBIMEDIA.COM CRONEMAGAZINE.COM SAGEWOMAN.COM WITCHESANDPAGANS.COM

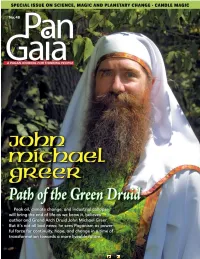

Winter ’08 PanGaia #48 1 BBIMEDIA.COM CRONEMAGAZINE.COM SAGEWOMAN.COM WITCHESANDPAGANS.COM Magazines that feed your soul and liven your spirits. Navigation Controls Availability depends on reader. Previous Page Toggle Next Page Bookmarks First Page Last Page ©2010 BBI MEDIA INC . P O BOX 678 . FOREST GROVE . OR 97116 . USA . 503-430-8817 PanGaia: A Pagan Journal for Thinking People SPECIAL SECTION: SCIENCE, MAGIC, AND PLANETARY CHANGE Peak Oil, Industrial Collapse, and What Pagans Can Do About It As members of the Pagan community in the first decade of the 21st century, we need to face up to the hard realities of a world in crisis. By John Michael Greer … 23 After the House of Straw: Pagan Perspectives on Peak Oil As a Neo-Pagan I’m accustomed to see in de- struction the potential for renewal. That could be the case for Peak Oil as well, but we must begin a transition to a saner, more sustainable way of life soon. In some respects, we Neo-Pagans — who keep close ties to the earth and will endure hard- ships to practice our faith — may thrive in this new time. By Burdock … 27 When the Wheel Wobbles: a Witch’s View of Climate Change After years of celebrating them, I’ve learned to appreciate the unique energy of the eight Sabbats. I’ve also learned to recognize the often subtle but always powerful shift in energy that occurs as one Sabbat passes into the next. But what would it be like if Beltaine no longer felt ON THE COVER: like Beltaine? By Treesong … 31 John Michael Greer — Path of the Green Druid Best known for his work in ceremonial magic and Why We Love the Apocalypse: Druidry, John Michael Greer also maintains a passion- Religious Roots of Peak Oil Doomerism ate interest in the environment. -

John Michael Greer

This document is online at: http://ratical.org/ratville/AoS/JMGreer102514.html Editor’s note: this transcript was made using the audio recording located inside: http://ifg.org/v2/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/. Left-mouse click the local copy here at – <IFG-JohnMGreer2014.mp3> – to download the mp3 file to your machine. This presentation of John Michael Greer was recorded at the International Forum on Globalization’s Techno-Utopianism & The Fate Of The Earth Teach-In held in New York City on October 25-26, 2014. John Michael Greer: False Promises IFG Teach-In: Techno-Utopianism & The Fate of the Earth Great Hall of the Cooper Union, New York City October 25, 2014 Introduction by Richard Heinberg Next I'm very happy to introduce my good friend John Michael Greer who describes himself as an historian of ideas which may just be a fancy way of saying he's a really smart and entertaining person. He's the author of 30 books including The Wealth of Nature: Economics as if Survival Mattered (2011) and one which is in the pipeline right now called After Progress: Reason and Religion at the End of the Industrial Age (2015) which I'm very much looking forward to. He's also the author of The Archdruid Report which is a weekly blog that I highly recommend you tune in to John's weekly musings. Happy to introduce John Michael Greer. Thank you Richard. The points that Dr. Huesemann has made are crucial to keep in mind. Because, of course, he’s quite correct.