Volume II RISING to the TOP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Common Spelling Errors in Student's

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.5.Issue 3. 2017 Impact Factor 5.002 (COSMOS) http://www.rjelal.com; (July-Sept) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE OVERVIEW OF COMMON SPELLING ERRORS IN STUDENT’S EXAMINATION SCRIPTS IN COMMUNICATION SKILLS: A DISTURBING PHENOMENON IN TAMALE POLYTECHNIC, GHANA RAFIU AYINLA SULEIMAN (PhD) Tamale Polytechnic, P. O Box 3 e/r, School of Applied Arts, Department of Languages and Liberal Studies Tamale-Ghana [email protected] ABSTRACT The English Language has become the world’s most important language today with half a billion speakers – in science and technology, commerce, trade, in the arts and international diplomacy. This study, therefore, investigated common spelling errors in students communicative skills examination scripts which have unspeakable consequences on their academic performance and professional life with a view to arresting this deficiency. Kohler’s theory of Learning by Insight was adopted using survey and in-depth interviews. Five HND departments were purposively selected- Building Technology, Electrical/Electronics, Agricultural Engineering, Accounting and Information and Communication Technology. Three hundred and sixty scripts were randomly selected. In-depth interviews were conducted on this sample using convenience sampling technique. Majority (61%) of the students write poor spelling and most (75%) moderately performed low in examination as a result of inadequate qualified English teachers at the basic and Senior High Schools, student’s own attitude to English language learning and acquisition, improper use of method of teaching English, inadequate instructional materials coupled with lack of language laboratory for teaching English Language. -

The Leland Initiative: Africa Global Information Infrastructure Gateway Project (698-0565)

The Leland Initiative: Africa Global Information Infrastructure Gateway Project (698-0565) Strategic Objective 3: End-User Applications Internet for Development: Applications and Training School-to-School Partnership Ghana February 17 -18, 1997 Prepared for: United States Agency for International Development Africa Bureau, Office of Sustainable Development USAID/Accra Prepared by: Zoey Breslar United States Agency for International Development Policy and Program Coordination Center for Development Information and Evaluation Research and Reference Services Project operated by the Academy for Educational Development March 1997 Introduction The purpose of the Leland Initiative’s School-to-School Partnership program is to promote win-win partnerships between schools in Africa and the United States via the Internet. In African countries, this Initiative, in conjunction with the USAID mission’s bilateral funds, may assist schools in becoming aware of the academic uses of the Internet, and in acquiring the hardware and training needed to participate in the Partnership. The benefits of the Leland Initiative’s School-to-School Partnership are four-fold. First, it gives students a meaningful introduction to new technologies and provides them with the skills and the means to access resources previously unavailable due to high communications costs and limited communications technologies in Africa. Second, it aids faculty and administrators to enhance their skills and provides them with resources to further develop their curricula. Third, the dialogue and projects created through this Partnership will enrich the African resources available on the Internet, supplying much-needed information about Africa to the world. These are linkages essential to today’s global economy, the means by which Africa will leapfrog into the 21st century. -

PROFESSOR NKETIA BROCHURE FINAL PRINT FILE.Cdr

# v v Nketia Kwabena Celebrating a Legend Joseph Hanson Joseph Emeritus Professor Emeritus K K R R e e r r d d J J v v K K k k r r g Rg R e e O O 9 9 o o 0 0 J J J J 0 0 1921-2019 P P P P U U r r p p O O j j s s K K g g j j O O p p r U r U P P P P 0 0 J J J J 0 0 o o 9 9 O O e e R R g g r kr k K K v v J J d d r er e R R K K v v Emeritus Professor Joseph Hanson Kwabena Nketia Emeritus Professor Joseph Hanson Kwabena Nketia Officiating Ministers Rt. Rev. Prof. J.O.Y. Mante Moderator of the General Assembly of Presbyterian Church of Ghana (P.C.G.) Rev. Dr. Samuel Ayete-Nyampong Clerk of the General Assembly of P.C.G. Rev. Dr. Victor Oko Abbey Chairperson, Ga Presbytery Rev. Solomon Nii Mensah Adjei Clerk Ga Presbytery Rev. Daniel Amoako Nyarko Chairperson Ga West Presbytery Most Rev. Prof. Emmanuel Asante Former Presiding Bishop of the Methodist Church Ghana, Accra Rev. Prof. Asamoah- Gyadu President, Trinity Theological Seminary, Legon Rev. M.G. Anim-Tetey District Minister, Madina Rev. Capt. (GN) P. Adjei-Djan Director of Religious Affairs, Ghana Armed Forces Other Clergy Rev. Roy Asiamah Faith Congregation, Madina Rev. Dr. Martin Adu Obeng Redemption Congregation, Madina Rev. -

![[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 Prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 Prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 Prepared 03/03](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5636/ghanabib-1819-1979-prepared-23-11-2011-ghanabib-1980-1999-prepared-30-12-2011-ghanabib-2000-2005-prepared-03-03-6245636.webp)

[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 Prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 Prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 Prepared 03/03

[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 prepared 03/03/2012] [Ghanabib 2006 – 2009 prepared 09/03/2012] GHANAIAN THEATRE A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES A WORK IN PROGRESS BY JAMES GIBBS File Ghana. Composite on ‘Ghana’ 08/01/08 Nolisment Publications 2006 edition The Barn, Aberhowy, Llangynidr Powys NP8 1LR, UK 9 ISBN 1-899990-01-1 The study of their own ancient as well as modern history has been shamefully neglected by educated inhabitants of the Gold Coast. John Mensah Sarbah, Fanti National Constitution. London, 1906, 71. This document is a response to a need perceived while teaching in the School of Performing Arts, University of Ghana, during 1994. In addition to primary material and articles on the theatre in Ghana, it lists reviews of Ghanaian play-texts and itemizes documents relating to the Ghanaian theatre held in my own collection. I have also included references to material on the evolution of the literary culture in Ghana, and to anthropological studies. The whole reflects an awareness of some of the different ways in which ‘theatre’ has been defined over the decades, and of the energies that have been expended in creating archives and check-lists dedicated to the sister of arts of music and dance. It works, with an ‘inclusive’ bent, on an area that focuses on theatre, drama and performance studies. When I began the task I found existing bibliographical work, for example that of Margaret D. Patten in relation to Ghanaian Imaginative Writing in English, immensely useful, but it only covered part of the area of interest. -

School Aid 2013 / 2014

Ghana School Aid 2013 / 2014 Chairman’s Report Dr Judith Gillespie Smith, a GSA supporter and AKWAABA! committee member, has sadly had to resign Where has the past year gone? The annual recently due to ill health. Judith was with the general meeting of 2012 held at the John Adams Ghana Ministry of Agriculture based near to Hall brought together a group of supporters Kumasi and spent a little time in Accra. She from different backgrounds who have a specialised in the eradication of pests which passion towards giving the children of Ghana affected the crops which were grown in the opportunities of enjoying a good education. Ashanti Region, and the programme was to On that occasion we were fortunate enough destroy the parasites which caused so much to have Lord Paul Boateng, who gave his time damage to the farms. She was in Ghana from to address our meeting. Like all of us, Paul January 1961 to September 1964 and found shares our enthusiasm for the work we are her experiences most rewarding. She was for doing, especially in the Northern and Upper twelve years a staunch member of the Ghana regions. He is trying to identify a school in the Tamale district which would benefit from our support. Also present was my former colleague Nick Elam who is well known to our members in that he chaired the Caine Prize for African Literature which in the past has been awarded to Ghanaian writers. Both Paul and Nick emphasised how well educated a minority of Ghanaians have become and they are enthusiastic over the way we are creating openings for a few more. -

CELEBRATING REV. MRS. AYIKAILE ARYEETEY 10 to Greater Glory

1 CELEBRATING REV. MRS. AYIKAILE ARYEETEY AN AMAZING MUM, MORE PRECIOUS THAN JEWELS Miss J An epitome of love you were. Yours was a heart filled with pure gold Outflowing with love to all and sundry. Sacrificing so much for the good of others. Always ready to share other’s burdens. O such blessing to have you as our mother! Thank you Lord for the best mum of all. CELEBRATING REV. MRS. AYIKAILE ARYEETEY 2 Order of Service Officiating Ministers PART ONE 3. Vote of Thanks and Announcements: • Most Rev. G. N Kotey PRE-BURIAL SERVICE Elder Eddie Dsani Leader, The Church of 4. Benediction -Rev. Kweku Stephen Christ(SM) 1. Opening Hymn - MHB 1 5. Recessional Hymn / Choruses • Rev. Mrs. Gifty Kotey (O for a thousand tongues to The Church of Christ (SM) sing) PART THREE (Grave Side) • Rev. Kweku Stephen 2. File Past - MHB 525, 215, 73, The Church Of Christ (SM) 679, 628, 830, 831, 1. Hymn - MHB 235 (I know that my • Rev. Mrs. Grace Halm-Lutterodt 3. Opening Prayer Redeemer lives) The Church Of Christ (SM) 4. Biography/Tributes 2. Sentences & Exhortation: • Rev. Francis Pappoe 5. Hymn - MHB 251 Rev. Adotei E. Abrahams The Church Of Christ (SM) (Omnipotent Redeemer) / 3. Hymn/Chorus - MHB 976 (Now the • Rev. Adotei E. Abrahams Choruses labourer's task is o'er.) The Church Of Christ (SM) 6. Scripture Reading: 4. Committal & Prayer, Wreath Laying - Psalm 39: 4-13 Rev Adotei E. Abrahams In Attendance: 7. Worship: - MHB 34 5. Hymn - MHB 914 (God be with you • Rt. Rev. -

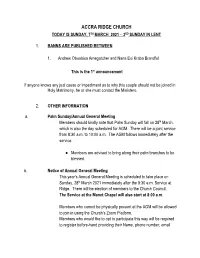

Week 1 Notice

ACCRA RIDGE CHURCH TH RD TODAY IS SUNDAY, 7 MARCH 2021 – 3 SUNDAY IN LENT 1. BANNS ARE PUBLISHED BETWEEN 1. Andrew Obuobisa Amegatcher and Nana Esi Kraba Brandful st This is the 1 announcement If anyone knows any just cause or impediment as to why this couple should not be joined in Holy Matrimony, he or she must contact the Ministers. 2. OTHER INFORMATION a. Palm Sunday/Annual General Meeting th Members should kindly note that Palm Sunday will fall on 28 March, which is also the day scheduled for AGM. There will be a joint service from 8:30 a.m. to 10:00 a.m. The AGM follows immediately after the service. ● Members are advised to bring along their palm branches to be blessed. b. Notice of Annual General Meeting This year’s Annual General Meeting is scheduled to take place on th Sunday, 28 March 2021 immediately after the 9:30 a.m. Service at Ridge. There will be election of members to the Church Council. The Service at the Manet Chapel will also start at 8:00 a.m. Members who cannot be physically present at the AGM will be allowed to join in using the Church’s Zoom Platform. Members who would like to opt to participate this way will be required to register before-hand providing their Name, phone number, email address and their Church Membership Number. On confirmation, Member will receive the link to join the meeting on the scheduled date. A message will be sent by SMS and to Church-related WhatsApp groups on this process. -

Ridge School Prospectus 2020.Cdr

RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS RCS PROSPECTUS, RULES ®ULATIONS NOT ONLY WITH OUR LIPS BUT IN OUR LIVES P. O. BOX 2316, ACCRA RIDGE CHURCH SCHOOL RIDGE CHURCH SCHOOL 1. HISTORY OF THE SCHOOL Proposals to establish the Ridge Church School were accepted by the congregation of the Accra Ridge Church at the Annual General Meeting on 23rd January 1955 and the Constitution of the church was amended to enable the Church Council to establish a school and to be responsible for its Management. An appeal for funds was launched and the generous response of members of the business community, the congregation and the services of honorary architects, quantity surveyors, consulting engineers and many other helpers enabled the council to build and open a school within two years. The foundation stone was laid on 26th October 1956 by the Rev. Arthur Collin Russell, C.M.G, the then Chairman of the Council and the School opened for the first time on 7th January 1957 with Mrs Ellen Stronge as Headmistress. To start with, there were only thirty three (33) children but numbers increased rapidly. The original buildings were extended in 1959, in 1961 and in 1966. A third stream was added in 1978 and the junior secondary school programme was initiated in 1987. The School started running the Kindergarten Two (KG 2) programme in September 2011 learners 3 RIDGE CHURCH SCHOOL 2. SCHOOL SITE AND BUILDINGS The School is situated on a quiet and shady site adjoining the Ridge Church at the junction of Gamel Abdul Nasser Avenue and Guinea Bissau Road. -

Ridge Church School

RIDGE CHURCH SCHOOL 1. HISTORY OF THE SCHOOL Proposals to establish the Ridge Church School were accepted by the congregation of the Accra Ridge Church at the Annual General Meeting on 23rd January 1955 and the Constitution of the church was amended to enable the Church Council to establish a school and to be responsible for its Management. An appeal for funds was launched and the generous response of members of the business community, the congregation and the services of honorary architects, quantity surveyors, consulting engineers and many other helpers enabled the council to build and open a school within two years. The foundation stone was laid on 26th October 1956 by the Rev. Arthur Collin Russell, C.M.G, the then Chairman of the Council and the School opened for the first time on 7th January 1957 with Mrs Ellen Stronge as Headmistress. To start with, there were only thirty three (33) children but numbers increased rapidly. The original buildings were extended in 1959, in 1961 and in 1966. A third stream was added in 1978 and the junior secondary school programme was initiated in 1987. The School started running the Kindergarten Two (KG 2) programme in September 2011. 2. SCHOOL SITE AND BUILDINGS The School is situated on a quiet and shady site adjoining the Ridge Church at the junction of Gamel Abdul Nasser Avenue and Guinea Bissau Road. While conveniently close to one of the main approaches to Accra from the North and East, it is far enough from main roads to be free from the noise and the danger of motor traffic to children. -

2016 Scripps National Spelling Bee Finalists

2016 SCRIPPS NATIONAL SPELLING BEE FINALISTS Speller No. 1, Erin Howard Adventure Travel, Birmingham, Alabama Age 12, 5th grade School: Mountain Gap P-8 School Hometown: Huntsville, Alabama, United States Erin thinks of herself as a very creative person. She enjoys creating her own worlds and putting them into writing and role-play games with friends, as well as composing and playing music on the piano. In fact, she won first place in the state of Alabama last year for her musical composition for the Parent Teacher Association's Reflections competition. If you can't find Erin at the piano or typing up a novella, you're sure to see her watching her favorite television show, Doctor Who. She considers herself a "huge nerd" because of her deep interests in science fiction, mythology and science. Erin wants to attend the Georgia Institute of Technology to take courses in biology and medicine. She dreams of becoming a pediatrician and joining the international organization M?decins Sans Fronti?res, or Doctors Without Borders.? Speller No. 5, Nicola Ferguson Arizona Educational Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona Age 14, 7th grade School: Sunrise Middle School Hometown: Phoenix, Arizona, USA At school, Nicola's favorite subjects are science and math, and she currently aspires to be a marine biologist. She also likes learning Mandarin. Nicola has been taking violin lessons and kung fu classes for many years. When she has free time, she enjoys spending time online at Khan Academy and YouTube. She also relishes reading. Some of her favorites are the Ranger's Apprentice series, The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and the Harry Potter novels.