Concordia Theological Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Theology of Creation Lived out in Christian Hymnody

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-1-2014 A Theology of Creation Lived Out in Christian Hymnody Beth Hoeltke Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/phd Part of the Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hoeltke, Beth, "A Theology of Creation Lived Out in Christian Hymnody" (2014). Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation. 58. https://scholar.csl.edu/phd/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A THEOLOGY OF CREATION LIVED OUT IN CHRISTIAN HYMNODY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Department of Doctrinal Theology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Beth June Hoeltke May 2014 Approved by Dr. Charles Arand Advisor Dr. Kent Burreson Reader Dr. Erik Herrmann Reader © 2014 by Beth June Hoeltke. All rights reserved. Dedicated in loving memory of my parents William and June Hoeltke Life is Precious. Give it over to God, our Creator, and trust in Him alone. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

Lutherans for Lent a Devotional Plan for the Season of Lent Designed to Acquaint Us with Our Lutheran Heritage, the Small Catechism, and the Four Gospels

Lutherans for Lent A devotional plan for the season of Lent designed to acquaint us with our Lutheran heritage, the Small Catechism, and the four Gospels. Rev. Joshua V. Scheer 52 Other Notables (not exhaustive) The list of Lutherans included in this devotion are by no means the end of Lutherans for Lent Lutheranism’s contribution to history. There are many other Lutherans © 2010 by Rev. Joshua V. Scheer who could have been included in this devotion who may have actually been greater or had more influence than some that were included. Here is a list of other names (in no particular order): Nikolaus Decius J. T. Mueller August H. Francke Justus Jonas Kenneth Korby Reinhold Niebuhr This copy has been made available through a congregational license. Johann Walter Gustaf Wingren Helmut Thielecke Matthias Flacius J. A. O. Preus (II) Dietrich Bonheoffer Andres Quenstadt A.L. Barry J. Muhlhauser Timotheus Kirchner Gerhard Forde S. J. Stenerson Johann Olearius John H. C. Fritz F. A. Cramer If purchased under a congregational license, the purchasing congregation Nikolai Grundtvig Theodore Tappert F. Lochner may print copies as necessary for use in that congregation only. Paul Caspari August Crull J. A. Grabau Gisele Johnson Alfred Rehwinkel August Kavel H. A. Preus William Beck Adolf von Harnack J. A. O. Otteson J. P. Koehler Claus Harms U. V. Koren Theodore Graebner Johann Keil Adolf Hoenecke Edmund Schlink Hans Tausen Andreas Osiander Theodore Kliefoth Franz Delitzsch Albrecht Durer William Arndt Gottfried Thomasius August Pieper William Dallman Karl Ulmann Ludwig von Beethoven August Suelflow Ernst Cloeter W. -

Lutheran Layout II

What’s New Welcome to Our Catalog Marty Haugen . .4-5 John Ferguson . .6 Taizé . .7 Liturgies . .8-9 New Releases for a New Millennium from GIA Herman Stuempfle books . .10 Hymn Resources . .11 A glorious choral festival as Instrumental Music . .12 only John Ferguson can create Order Form . .13 with the St. Olaf Cantorei... Choral Music . .14-18 Organ/Piano Music . .19 A Thousand Ages: A Celebration of Hope...page 6 Psalms . .20 Ars Antiqua Choralis . .21 Part of the Soli Deo Gloria Iona . .22 Collection... Reprint License . .23 Come Let Us Sing for Joy: A Morning Prayer Service and To our Lutheran customers: Beneath the Tree of Life, an In October 1999, the historic signing of the Concordat between the ecumenical communion service Roman Catholic Church and several Lutheran church bodies reminded us by Marty Haugen...pp. 4-5 again of the common heritage which many denominations share, and of the desire to work toward even greater cooperation in the future.Today, as For worship leaders, in the past, it seems as though the church is always undergoing a process composers...anyone looking of reformation. The past twenty-five years have seen many worshiping for inspirational texts... communities search for meaningful and useful ways to worship. The task of doing worship has never been more challenging or more interesting Awake Our Hearts to Praise! than it is today. The Hymns of Herman GIA offers an incredible diversity of resources for worship and Stuempfle...page 10 music—from choral works of the old masters to modern settings of the psalms, from Gregorian chant to contemporary instrumental works, from Take a look at our choral and hymn concertato settings to gospel-style music. -

Oh Come, Let Us Worship! Page 2

O Come, Let Us Worship! Rev. Mark E. DeGarmeaux 1995 Synod Convention Essay A Study in Lutheran Liturgy and Hymnody I. The Church Service II. The Church Song Christian music on earth is nothing but a foretaste of or a Prelude to everlasting life, since here we only intone and sing the Antiphons until through temporal death we sing the Introit and the Sequence, and in everlasting life the true Completory and the Hymns in all eternity. Nikolaus Selnecker I. The Church Service O come, let us sing to the LORD Let us make a joyful noise to the Rock of our salvation. Let us come before His presence with thanksgiving Let us make a joyful noise to Him with psalms. For the LORD is the great God And the great King above all gods. In His hand are the deep places of the earth; The heights of the hills are His also. The sea is His, for He made it; And His hands formed the dry land. O come, let us worship and bow down Let us kneel before the LORD our Maker. For He is our God, And we are the people of His pasture, And the sheep of His hand. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost; as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, forevermore. Amen. (Psalm 95, the Venite from the Office of Matins) God created our world perfect and in harmony with Himself and His holiness. All the earth was to serve man and glorify God, so "let everything that has breath praise the LORD" (Psalm 150:6). -

The New Song Never Ends Hymns, Songs, & Spiritual Songs

The New Song Never Ends Hymns, Songs, & Spiritual Songs Scott M. Hyslop The New Song Never Ends Hymns, Songs, & Spiritual Songs Scott M. Hyslop For my parents James and Marlys Hyslop “I was glad when they said unto me, let us go into the house of the Lord” Psalm 122 The New Song Never Ends Hymns, Songs, & Spiritual Songs Scott M. Hyslop Printed on recycled and acid-free paper The New Song Never Ends: Hymns, Songs, & Spiritual Songs Copyright © 2017 Selah Publishing Co., Inc., Pittsburgh, Pa. 15227 www.selahpub.com All rights reserved. All pieces in this collection are under copyright protection of the copyright holder listed with each hymn. Permission must be obtained from the copyright holder to reproduce—in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise—what is included in this book. All of the hymns included may be used by congregations enrolled in the C.C.L.I., LicenSing, or OneLicense.net programs. Typeset and printed in the United States of America. First edition 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 20 19 18 17 Catalog no. 125-052 Foreword The last half of the 20th-century and the early years of the 21st-century have seen a remarkable outpouring of new hymns, psalms, and spiri- tual songs—both texts and music. It is an outpouring quite unprece- dented since the time of Pietism in the late 17th- and early 18th- centu- ries, and the periods of revival in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Scott M. Hyslop’s collection The New Song Never Ends: Hymns, Songs, & Spiritual Songs is one of the most recent and more interesting com- pilations to appear. -

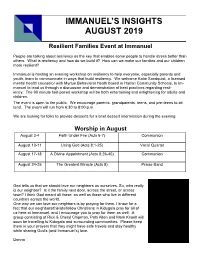

Immanuel's Insights August 2019

IMMANUEL’S INSIGHTS AUGUST 2019 Resilient Families Event at Immanuel People are talking about resiliency as the key that enables some people to handle stress better than others. What is resiliency and how do we build it? How can we make our families and our children more resilient? Immanuel is hosting an evening workshop on resiliency to help everyone, especially parents and youth, learn to communicate in ways that build resiliency. We welcome Katie Sandquist, a licensed mental health counselor with Myrtue Behavioral Heath based in Harlan Community Schools, to Im- manuel to lead us through a discussion and demonstration of best practices regarding resil- iency. The 90 minute fast-paced workshop will be both entertaining and enlightening for adults and children. The event is open to the public. We encourage parents, grandparents, teens, and pre-teens to at- tend. The event will run from 6:30 to 8:00 p.m. We are looking for folks to provide desserts for a brief dessert intermission during the evening. Worship in August August 3-4 Faith Under Fire (Acts 6-7) Communion August 10-11 Using God (Acts 8:1-25) Vocal Quartet August 17-18 A Divine Appointment (Acts 8:26-40) Communion August 24-25 The Greatest Miracle (Acts 9) Praise Band God tells us that we should love our neighbors as ourselves. So, who really is our neighbor? Is it the family next door, across the street, or across town? I think God meant all those, as well as those who live in different countries across the world. -

St. Matthew's Lutheran

St. Matthew’s Lutheran The First Sunday After Christmas Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod December 26 & 27, 2020 766 West Wabasha Street, Winona MN 55987 Church Phone: 507.452.2085 “Peace on Earth” School Phone: 507.454.3083 www.stmatthewswinona.org WELCOME www.facebook.com/stmatthewswinona Welcome and thank you for joining us for worship today! In our service we gather be- fore our gracious God to offer him our worship and praise. We assemble to hear God’s holy and powerful Word. Through this Word, God strengthens our faith and brings us ever closer to our eternal home. PRAYER BEFORE WORSHIP Dear God, let your Word shine in our hearts by your Holy Spirit. Make it so bright and warm that we always find our comfort and joy in it. Amen. Out of courtesy for your fellow worshipers please also silence all electronic devices. OUR FACILITIES A restroom is located in the Mother’s Room at the back of church and also in the church basement. There is also a handicapped accessible restroom in the back of church. Ask an usher for help and directions. The members of St. Matthew’s believe that families should be allowed to worship together. If the need arises, we have an audio-equipped children’s room just outside of the church doors to your left. If you need anything during the service, please feel free to ask an usher. Pastor Matthew Schoell 1.507.615.0012 OUR COMMUNION PRACTICE [email protected] St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church still observes the biblical practice of close communion. -

Download Master List As A

2/14/19 THESES AND DISSERTATIONS RELATED TO HYMNOLOGY MASTER LIST A Aalders, Cynthia Yvonne. “To Express the Ineffable: The Problems of Language and Suffering in the Hymns of Anne Steele (1717-1778).” Th.M., Regent College, 2007. Abbott, Rebecca L. “‘What? Bound for Canaan’s Coast?’: Songs of Pilgrimage in the American Church.” M.A., Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, 2002. Abbott, Rebecca Nelson. “Developing a Curriculum of Spiritual Formation for Children Through the Hymns of Charles Wesley at First United Methodist Church, Georgetown, Kentucky.” D.W.S., Robert E. Webber Institute for Worship Studies, 2010. Abee, Michele. “‘Journey into the Square’: A Geographical Perspective of Sacred Harp.” M.A., University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2012. Abels, Paul Milford. “An Ecumenical Manual of Song for Young Churchmen.” S.M.M., Union Theological Seminary, 1965. Adams, Gwen E. “A Historical-Analytical Study of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Canonic Variations on the Christmas Hymn ‘Von Himmel Hoch, Da Komm’ Ich Her.’” M.M., Yale University, 1978. Adams, Nelson Falls. “The Musical Sources for John Wesley's Tunebooks: The Genealogy of 148 Tunes.” S.M.D., Union Theological Seminary, 1973. Adams, Robert Alvin. “The Hymnody of the Church of God (1885-1980) as a Reflection of that Church's Theological and Cultural Changes.” D.M.A., Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1980. Adekale, Elizabeth. “Christian Hymnody: Its Influence on African American Spirituals and Contemporary Christian Music.” M.A., Northeastern Illinois University, 2014. Adell, Marian Young. “Mystery–Body Lost, Body Found: The Decline, Loss and Recovery of the Body of Christ in Methodist Worship.” Ph.D., Drew University, 1994. -

Download a PDF File

Full list of hymlyrics available at http://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/hymnlyrics2/ The Three Kings of Cologne-Eugene Field Three Kings from Out the Orient-Thomas Brown Three in One, and One in Three-Gilbert Rorison Forty Days Thy Seer of Old-Jackson Mason The Ninety and Nine-Elizabeth Clephane As Above the Darkest Storm Cloud-Daniel Howard Are All the Foes of Sion Fools-Isaac Watts And Am I Only Born to Die-Charles Wesley Among th'Assemblies of the Great-Isaac Watts At All Times Praise the Lord-John Howson ca Abba, Father! We Approach Thee-James Deck Abide Not in the Realm of Dreams-William Burleigh Abide with Me(Perkins)-Kate Perkins Abide with Me(Lyte)-Henry Lyte Abide with Us, the Day Is Waning-Caspar Boye Abiding in Jesus-Minnie Enlow Abide in Me, O Lord-Harriet Stowe Abiding, Oh, So Wondrous Sweet-Charles Root Abide with Me(Dietrich)-Emma Dietrich Abide in Thee-Joseph Smith Able to Deliver-Fanny Crosby Able to Save-Richard Venting Alas! By Nature How Depraved-John Newton Abode of Peace-Agata Rosenius Above the Hills of Time-Thomas Tiplady Above the Clear Blue Sky-John Chandler Above the Bright Blue-Charles Pollock Above the Starry Spheres-From the Latin Above Yon Clear Blue Sky-Mary Bourdillon Absent from Flesh! O Blissful Thought-Isaac Watts Abundant Fields of Grain Shall Wave-The Psalter And Can It Be That I Should Gain-Charles Wesley Accepted in the Beloved-Civilla Martin Accept Him Today-Howard Hastings According to Thy Gracious Word-James Montgomery At the Cross, Her Station Keeping-From the Latin And Can I Yet Delay-Charles -

JULY 2019 Westport Presbyterian Church Kansas City, Missouri

THE DIAPASON JULY 2019 Westport Presbyterian Church Kansas City, Missouri Cover feature on pages 22–23 PHILLIP TRUCKENBROD CONCERT ARTISTS ANTHONY & BEARD ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO PETER RICHARD CONTE CONTE & ENNIS DUO LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD MARTIN JEAN HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE LOUPRETTE & GOFF DUO ROBERT MCCORMICK BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAéL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN ROBIN & LELEU DUO BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH JOSHUA STAFFORD THOMAS GAYNOR 2016 2017 LONGWOOD GARDENS ST. ALBANS WINNER WINNER IT’S ALL ABOUT THE ART ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ 860-560-7800 ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚͬWŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Tenth Year: No. 7, Responses to our digitization project request Whole No. 1316 I have been amazed that several of our readers have gener- JULY 2019 ously responded to my request to provide missing copies of vin- Established in 1909 tage magazines for use in our digitization project. At this time, Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 it appears we have fi lled in many of these gaps, and we are 847/954-7989; [email protected] acquiring copies of many issues dating back to the 1930s. Please www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, stay tuned for further updates on this important endeavor to the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music make our website one of the world’s fi nest for organ and church Our cover feature this month is Pasi Organbuilders Opus music research! Visit www.thediapason.com often! The website 24, recently completed for Westport Presbyterian Church, CONTENTS is continuously updated with news, events, and more. -

The Community of St. Philip at Worship Trinity Sunday June 7, 2020

The Community of St. Philip at Worship Trinity Sunday June 7, 2020 Voluntary Dieu est simple — Les Trois sont Un Olivier Messiaen (God is simple — The Three are One) (1908–1992) from Méditations sur le mystère de la Sainte Trinité (1969) (Meditations on the mystery of the Holy Trinity) Opening Sentences Hymn 393 (see last page) O Day of Rest and Gladness ES FLOG EIN KLEINS WALDVÖGELEIN Prayer of Confession Gracious God, our sins are too heavy to carry, too real to hide, and too deep to undo Forgive what our lips tremble to name, what our hearts can no longer bear, and what has become for us a consuming fire of judgment. Set us free from a past that we cannot change; open to us a future in which we can be changed; and grant us grace to grow more and more in your likeness and image; through Jesus Christ, the light of the world. silent prayer Holy One, in your mercy. Hear our prayer. Declaration of Forgiveness Believe the Good News. In Jesus Christ we are forgiven. Response Words of Peace In Christ, God is reconciling the whole world, and God is entrusting to us the message of reconciliation. We are ambassadors for Jesus Christ. God’s appeal is being made through us. Peace be with you. Peace be with all. Prayer for Illumination Gospel Reading Matthew 28:16-20 Solo Laus Trinitatis | Praise to the Trinity Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) O praise be to you Holy Trinity resounding jubilation and life of all that is. To our Mother Great Creator of all things living and of life itself. -

Reformation 500

REFORMATION 500 As we kicked off the year of the Reformation’s 500th anniversary, Living Lutheran began a series in which we highlighted 500 items about the Reformation and its spirit and impact. Over the course of 10 issues, we explored 500 unique aspects of the Reformation, beginning with 50 wide-ranging quotes. These lists were not meant as an all-encompassing compendium of everything essential to the Reformation and its theology, but rather as a glimpse of the variety of ways the movement that Martin Luther sparked in 1517 would influence the history of the world. Contents 50 Reformation quotes 2 50 Reformation sites 7 50 Reformation figures 11 50 Reformation artworks 16 50 Reformation publications 21 50 things you may not know about Luther 26 50 things you may not know about the Reformation 31 50 things Luther taught that you may not know 36 50 Reformation hymns 41 50 ways the Reformation still impacts pastors 46 VOICES OF FAITH • LIVINGLUTHERAN.ORG • 2017 REFORMATION 500 50 Reformation quotes As we kick off the year of the Reformation’s 500th anniversary, Living Lutheran begins a series in which we’ll highlight 500 items about the Reformation and its spirit and impact. Over the course of the next 10 issues, we’ll explore 500 unique aspects of the Reformation, beginning this month with 50 wide-ranging quotes. This list is not meant as an all-encompassing compendium of everything essential to the Reformation and its theology, but rather as a glimpse of the variety of ways the movement that Martin Luther sparked in 1517 would influence the history of the world.