Medieval Deer Parks in the Lidar Study Area Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement to Agenda Agenda Supplement for Cabinet, 04/10

Public Document Pack JOHN WARD East Pallant House Head of Finance and Governance Services 1 East Pallant Chichester Contact: Graham Thrussell on 01243 534653 West Sussex Email: [email protected] PO19 1TY Tel: 01243 785166 www.chichester.gov.uk A meeting of Cabinet will be held in Committee Room 1 at East Pallant House Chichester on Tuesday 4 October 2016 at 09:30 MEMBERS: Mr A Dignum (Chairman), Mrs E Lintill (Vice-Chairman), Mr R Barrow, Mr B Finch, Mrs P Hardwick, Mrs G Keegan and Mrs S Taylor SUPPLEMENT TO THE AGENDA 9 Review of Character Appraisal and Management Proposals for Selsey Conservations Area and Implementation of Associated Recommendations Including Designation of a New Conservation Area in East Selsey to be Named Old Selsey (pages 1 to 12) In section 14 of the report for this agenda item lists three background papers: (1) Former Executive Board Report on Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work - 8 September 2009 (in the public domain). (2) Representation form Selsey Town Council asking Chichester District Council to de-designate the Selsey conservation area (3) Selsey Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Proposals January 2007 (in the public domain). These papers are available to view as follows: (1) is attached herewith (2) has been published as part of the agenda papers for this meeting (3) is available on Chichester District Council’s website via this link: http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5298&p=0 http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5299&p=0 Agenda Item 9 Agenda Item no: 8 Chichester District Council Executive Board Tuesday 8th September 2009 Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work 1. -

South Downs Way Challenge…Virtually Week 3 –Buriton To

South Downs Way Challenge…Virtually Week 3 –Buriton to Cocking Hill ... 11 miles. Last week our walk took us from Exton to the eastern edge of the QE2 Country Park and Buriton, approx 24 miles from the start. Keep doing your steps in front of the TV, and this week let’s go from march around the block and prepare to walk from Buriton to Cocking Hill. We start uphill initially, along a small lane that then follows the undulating line of the escarpment overlooking Harting to the north. We've walked five miles to Harting Hill and from here we descend the grassy slope into the valley and then the footpath climbs steeply up to the fort at Beacon Hill. The fort was first built in the Bronze Age (8th Century BC to 6th Century BC), and updated during the Iron Age. Alternatively, following the bridlepath, we can traverse the hill, climbing more gently but eventually reaching the other side just beneath the summit of Beacon Hill. A slight incline then, the only way is down, sweeping into another timeless valley, then steeply up a chalky track through the trees. As you near the top of Philliswood Down look out for the memorial to a German pilot who was shot down and died here, on the very first day of the Battle of Britain on 13 August 1940. Just beyond and a sharp left turn takes us past the The Devil's Jumps, the best example of a Bronze Age barrow formation in Sussex. According to Wikipedia, “The Devil's Jumps are a group of five large bell barrows situated on the South Downs 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) south-east of Treyford in the county of West Sussex in southern England. -

13742 the London Gazette, Ist November 1977 Home Office

13742 THE LONDON GAZETTE, IST NOVEMBER 1977 CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENTS Black Notley Parish Council and People. Bleasby, People of COM(77) 483 FINAL Bletchingley Women's Institute. R/2347/77. Commission communication to the Council on Blockley Parish Council. the energy situation in the Community and in the world. Borley, People of Boughton Aluph and Eastwell, People of COMMISSION DOCUMENT DEPOSITED SEPARATELY Boys' Brigade. R/2131/77. Letter of amendment to the preliminary draft Brackley, People of general budget of the European Communities for 1978. Bracknell Development Corporation. Bracknell District Council. COM(77) 467 FINAL Braintree District Council and People. R/2361/77. Report from the Commission to the Council on Braunstone, People of the application to exported products of Council Regula- Breadsall, People of tion (EEC) No. 2967/76 laying down common standards Brighton Corporation. for the water content of frozen and deep-frozen chickens, British Association of Accountants and Auditors. hens and cocks. British Bottlers Institute. British Constitution Defence.Committee (Liverpool). COM(77) 443 FINAL British Dental Association. R/2355/77. Commission communication to the Council on 'British Medical Association. improving co-ordination of national economic policies. British Optical Association. COM(77) 473 FINAL British Railways Board. Bromesberrow Parish Council. R/23 87/77. Report on the opening, allocation and manage- Bromley Corporation. ment of the Community tariff quota in 1977 for frozen Brook, Milford Sandhills, Witley and Wormley, People of beef and veal. Broxtowe District Council. COM(77) 494 FINAL Buckingham Town Council. R/2473/77. Annual Report on the economic situation in the Burnham-on-Sea and Highbridge Town Council. -

CDAS – Chairman's Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We Still Plan to Do the Geophysical Survey at Fishbourne Once

CDAS – Chairman’s Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We still plan to do the geophysical survey at Fishbourne once the weather improves and the field starts to dry out. Coastal Monitoring Following the visit to Medmerry West in January we made a visit to Medmerry East. Recent storms had made a big change to the landscape. As on our last visit to the west side it was possible to walk across the breach at low tide. Some more of the Coastguard station has been exposed. However one corner has now disappeared. It was good that Hugh was able to create the 3D Model when he did. We found what looks like a large fish trap with two sets of posts running in a V shape, each arm being about 25 metres long. The woven hurdles were clearly visible. Peter Murphy took a sample of the timber in case there is an opportunity for radiocarbon dating. We plan to return to the site in March to draw and record the structure. When we have decided on a date for this work I will let Members know. Condition Assessment – Thorney Island The annual Condition Assessment of the WW2 sites on Thorney Island will be on Tuesday 10th March, meeting at 09:30 at the junction of Thorney Road and Thornham Lane (SU757049). If you would like to join us and want to bring a car onto the base you need to tell us in advance, so please email the make, model, colour and registration number of your car to [email protected] by Friday 6 March. -

Planning Committee Reports Pack And

Public Document Pack JOHN WARD East Pallant House Director of Corporate Services 1 East Pallant Chichester Contact: Sharon Hurr on 01243 534614 West Sussex Email: [email protected] PO19 1TY Tel: 01243 785166 www.chichester.gov.uk A meeting of Planning Committee will be held virtually on Wednesday 31 March 2021 at 9.30 am MEMBERS: Mrs C Purnell (Chairman), Rev J H Bowden (Vice-Chairman), Mr G Barrett, Mr R Briscoe, Mrs J Fowler, Mrs D Johnson, Mr G McAra, Mr S Oakley, Mr R Plowman, Mr H Potter, Mr D Rodgers, Mrs S Sharp and Mr P Wilding AGENDA 1 Chairman's Announcements Any apologies for absence which have been received will be noted at this stage. The Planning Committee will be informed at this point in the meeting of any planning applications which have been deferred or withdrawn and so will not be discussed and determined at this meeting. 2 Approval of Minutes (Pages 1 - 10) The minutes relate to the meeting of the Planning Committee held on 3 March 2021. 3 Urgent Items The chairman will announce any urgent items that due to special circumstances will be dealt with under agenda item 8 (b). 4 Declarations of Interests (Pages 11 - 12) Details of members’ personal interests arising from their membership of parish councils or West Sussex County Council or from their being Chichester District Council or West Sussex County Council appointees to outside organisations or members of outside bodies or from being employees of such organisations or bodies. Such interests are hereby disclosed by each member in respect of agenda items in the schedule of planning applications where the Council or outside body concerned has been consulted in respect of that particular item or application. -

Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions

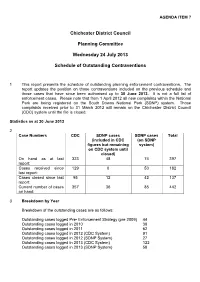

AGENDA ITEM 7 Chichester District Council Planning Committee Wednesday 24 July 2013 Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions 1 This report presents the schedule of outstanding planning enforcement contraventions. The report updates the position on those contraventions included on the previous schedule and those cases that have since been authorised up to 30 June 2013. It is not a full list of enforcement cases. Please note that from 1 April 2012 all new complaints within the National Park are being registered on the South Downs National Park (SDNP) system. Those complaints received prior to 31 March 2012 will remain on the Chichester District Council (CDC) system until the file is closed. Statistics as at 30 June 2013 2 Case Numbers CDC SDNP cases SDNP cases Total (included in CDC (on SDNP figures but remaining system) on CDC system until closed) On hand as at last 323 48 74 397 report: Cases received since 129 0 53 182 last report: Cases closed since last 95 12 42 137 report: Current number of cases 357 36 85 442 on hand: 3 Breakdown by Year Breakdown of the outstanding cases are as follows: Outstanding cases logged Pre- Enforcement Strategy (pre 2009) 44 Outstanding cases logged in 2010 38 Outstanding cases logged in 2011 62 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (CDC System) 91 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (SDNP System) 27 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (CDC System) 122 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (SDNP System) 58 4 Performance Indicators Financial Year 2013-2014 CDC Area Only a Acknowledge complaints within 5 days of receipt 92 -

Surrey Feet of Fines 1558-1760 Courtesy of Findmypast

Feet of Fines – Worcester references plus William Worcester publications: http://www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk Abstracts of Feet of Fines: Introduction The aim of this project is to provide abstracts of the medieval feet of fines that have not yet been published, for the period before 1509. A list of published editions, together with links to the abstracts on this site, can be found here. Alternatively, the abstracts can be searched for entries of interest. Background In the late 12th century a procedure evolved for ending a legal action by agreement between the parties. The agreement was known as a final concord (or fine). Originally this was a means of resolving genuine disputes, but by the middle of the 13th century the fine had become a popular way of conveying freehold property, and the legal action was usually a fictitious one, initiated with the cooperation of both parties. This procedure survived until the 1830s. Originally, each party would be given a copy of the agreement, but in 1195 the procedure was modified, so that three copies were made on a single sheet of parchment, one on each side and one at the foot. The copies would then be separated by cutting the parchment along indented (wavy) lines as a precaution against forgery. The right and left hand copies were given to the parties and the third copy at the foot was retained by the court. For this reason the documents are known as feet of fines. The following information is available online: Court of Common Pleas, General Eyres and Court of King's Bench: Feet of Fines Files, Richard I - Henry VII (to 1509) and Henry VIII - Victoria (from 1509) (descriptions of class CP 25 in The National Archives online catalogue) Land Conveyances: Feet of Fines, 1182-1833 (National Archives information leaflet) [Internet Archive copy from August 2004] CP 25/1/45/76, number 9. -

The London Gazette, 17 April, 1925

2620 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 17 APRIL, 1925. Boad from the Angmering—Clapham road Gatehouse Lane from the Midhurst—Peters- near Avenals Farm to the Arundel—Worthing field road at Cumberspark Wood via Gatehouse road about 600 yards east of the Woodman's to the road junction at Terwick Common about Arms. 200 yards west of Dangstein Lodge. Boad from South Stoke to the bridge over Boad from the Midhurst—Petersfield road the Biver Arun at Off ham including the branch near Lovehill Farm via Dumpford House and to the Black Babbit towards Offham Hanger. Nye Wood House to the Bogate—Bogate Broadmark Lane, Bustington, from the road Station road near Sandhill House. junction about 400 yards east of the Church Torberry Lane from the South Harting— to .the sea. Petersfield road at Little Torberry Hill to the Greyhound Inn. Boad from the South Harting—Petersfield Rural District of Horsham. road at the county boundary at Westons via Boad from the Horsham—Cowfold road near Byefield Cottages to the road junction at Newells Pond via Prings Farm, Peartree Cor- Brickkiln; Copse near Bival Lodge. ner and Stonehouse Farm to its junction with Garbitts Lane, Bogate, from the Midhurst— the Belmoredean—Partridge Green road at Petersfield road to the Bogate—Bogate Station Danefold Corner. road. Boad from tha road junction near Park Farm Boad from the Midhurst—Petersfield road at about 1$ miles north of Horsham via Lang- Fyning to the road junction at Terwick Com- hurst and Friday Street to the Clark's Green— mon about 200 yards west of Dangstein Lodge. -

The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond

T H A M E S V A L L E Y AARCHAEOLOGICALRCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment by Tim Dawson Site Code PLR12/80 (TQ 1793 7520) The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment for Renworth Homes (Southern) Ltd In support of a detailed planning application and Conservation Area Consent application for the erection of three new townhouses, with car parking and conversion of existing school building for six residential units with car parking by Tim Dawson Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code PLR 12/80 AUGUST 2012 Summary Site name: The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Grid reference: TQ 17925 75200 Site activity: Desk-based heritage assessment Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Tim Dawson Site code: PLR 12/80 Area of site: c.0.12ha Summary of results: The Old School lies in an area of high archaeological potential with finds and features dating from the Palaeolithic period onwards being discovered nearby. Richmond itself was an important centre with its royal palace dating from the medieval period. While construction of the school in 1870 is likely to have disturbed at least the most shallow archaeological deposits, the area under the playground is less likely to have been truncated allowing for the preservation of archaeologically sensitive layers. It is anticipated that it will be necessary to provide further information about the archaeological potential of the site from field observations, in order to draw up a scheme to mitigate the impact of the proposed residential development on any below-ground archaeological deposits if necessary. -

This Report Updates Planning Committee Members on Current Appeals and Other Matters

South Downs National Park Planning Committee Report of the Director Of Planning and Environment Services Schedule of Planning Appeals, Court and Policy Matters Date between 21/06/2019 and 19/07/2019 This report updates Planning Committee members on current appeals and other matters. It would be of assistance if specific questions on individual cases could be directed to officers in advance of the meeting. Note for public viewing via Chichester District Council web siteTo read each file in detail, including the full appeal decision when it is issued, click on the reference number (NB certain enforcement cases are not open for public inspection, but you will be able to see the key papers via the automatic link to the Planning Inspectorate). * - Committee level decision. 1. NEW APPEALS SDNP/18/06032/LIS Burton Mill, Burton Park Road, Barlavington, GU28 0JR - Duncton Parish Council Replacement of all existing windows with new double glazed units and revised frame design and reveal an obscured window. Case Officer: Beverley Stubbington Written Representation SDNP/18/06483/FUL East Marden Farm, Wildham Lane, East Marden, Marden Parish Council Chichester, West Sussex, PO18 9JE - Replacement of former agricultural buildings with 3 no. dwellings for tourism use. Case Officer: John Saunders Written Representation SDNP/18/05093/LDE Buryfield Cottage, Sheepwash, Elsted, Midhurst, West Elsted and Treyford Parish Sussex, GU29 0LA - Existing lawful development Council certificate for occupation of a dwellinghouse without complying with an agricultural occupancy condition. Case Officer: John Saunders Informal Hearing 2. DECIDED SDNP/18/01754/FUL Spindles East Harting Street East Harting Petersfield West Harting Parish Council Parish Sussex GU31 5LY - Replacement 1 no. -

The Earlier Parks Charles I's New Park

The Creation of Richmond Park by The Monarchy and early years © he Richmond Park of today is the fifth royal park associated with belonging to the Crown (including of course had rights in Petersham Lodge (at “New Park” at the presence of the royal family in Richmond (or Shene as it used the old New Park of Shene), but also the Commons. In 1632 he the foot of what is now Petersham in 1708, to be called). buying an extra 33 acres from the local had a surveyor, Nicholas Star and Garter Hill), the engraved by J. Kip for Britannia Illustrata T inhabitants, he created Park no 4 – Lane, prepare a map of former Petersham manor from a drawing by The Earlier Parks today the “Old Deer Park” and much the lands he was thinking house. Carlile’s wife Joan Lawrence Knyff. “Henry VIII’s Mound” At the time of the Domesday survey (1085) Shene was part of the former of the southern part of Kew Gardens. to enclose, showing their was a talented painter, can be seen on the left Anglo-Saxon royal township of Kingston. King Henry I in the early The park was completed by 1606, with ownership. The map who produced a view of a and Hatch Court, the forerunner of Sudbrook twelfth century separated Shene and Kew to form a separate “manor of a hunting lodge shows that the King hunting party in the new James I of England and Park, at the top right Shene”, which he granted to a Norman supporter. The manor house was built in the centre of VI of Scotland, David had no claim to at least Richmond Park. -

54880 Shripney Road Bognor.Pdf

LEC Refrigeration Site, Shripney Rd Bognor Regis, West Sussex Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Ref: 54880.01 esxArchaeologyWessex November 2003 LEC Refrigeration Site, Shripney Road, Bognor Regis, West Sussex Archaeological Desk-based Assessment Prepared on behalf of ENVIRON UK 5 Stratford Place London W1C 1AU By Wessex Archaeology (London) Unit 701 The Chandlery 50 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7QY Report reference: 54880.01 November 2003 © The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited 2003 all rights reserved The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 LEC Refrigeration Site, Shripney Road, Bognor Regis, West Sussex Archaeological Desk-based Assessment Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background...................................................................................1 1.2 The Site........................................................................................................1 1.3 Geology........................................................................................................2 1.4 Hydrography ..............................................................................................2 1.5 Site visit.......................................................................................................2 1.6 Archaeological and Historical Background.............................................2 2 PLANNING AND LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND .....................................8