P O E M M E M O Ir S to R Y 2 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

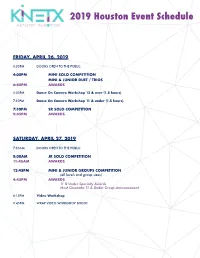

2019 Houston Event Schedule

2019 Houston Event Schedule FRIDAY, APRIL 26, 2019 3:30PM DOORS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC 4:00PM MINI SOLO COMPETITION MINI & JUNIOR DUET / TRIOS 6:45PM AWARDS 5:00PM Dance On Camera Workshop 12 & over (1.5 hours) 7:30PM Dance On Camera Workshop 11 & under (1.5 hours) 7:30PM SR SOLO COMPETITION 9:45PM AWARDS SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 2019 7:30AM DOORS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC 8:00AM JR SOLO COMPETITION 11:45AM AWARDS 12:45PM MINI & JUNIOR GROUPS COMPETITION (all levels and group sizes) 4:45PM AWARDS 11 & Under Specialty Awards Most Cinematic 11 & Under Group Announcement 6:15PM Video Workshop 9:45PM WRAP VIDEO WORKSHOP SHOOT 2019 Houston Event Schedule SUNDAY, APRIL 28, 2019 7:30AM DOORS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC 8:00AM TEEN SOLO COMPETITION (brief intermission) 11:45AM TEEN & SENIOR DUET / TRIOS 12:45PM AWARDS 1:30PM TEEN & SENIOR GROUP COMPETITION (all levels and group sizes) 3:45PM AWARDS 12 & Over Specialty Awards Most Cinematic 12 & Over Group Announcement 4:45PM MOST CINEMATIC JR GROUP VIDEO SHOOT (1 hour) 5:50PM MOST CINEMATIC SR GROUP VIDEO SHOOT (1 hour) 7:00PM That’s A Wrap! KINETIX: ARTISTRY IN MOTION APRIL 26 - 28, 2019 HOUSTON REGIONALS THE STAFFORD CENTRE FRIDAY, APRIL 26, 2019 START TIME: 4:00PM MINI SOLO COMPETITION MINI & JUNIOR DUET/TRIO COMPETITION 1 4:00 PM OH SO QUIET Solo Mini Showcase Musical 7–8 Gemma Riffel Enrich Theater Gymnastics and Dance Academy 2 4:02 PM HONEY HONEY Solo Mini Showcase Open 5–6 Hayes Hudspeth Living Art Dance Company 3 4:05 PM BOOGIE FEET Solo Mini Competitive Jazz 5–6 Myla Blanchard Amber Blanchard's School of Dance -

Avicii Stories Mp3, Flac, Wma

Avicii Stories mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Stories Country: Europe Style: House, Euro House, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1242 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1196 mb WMA version RAR size: 1484 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 335 Other Formats: AAC DMF XM APE WMA MOD MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Waiting For Love 1 3:51 Vocals – Simon Aldred Talk To Myself 2 3:56 Producer – Carl Falk Vocals – Sterling Fox Touch Me 3 3:06 Vocals – Celeste Waite Ten More Days 4 4:06 Vocals – Zak Abel For A Better Day 5 3:36 Vocals, Producer [Additional] – Alex Ebert Broken Arrows 6 3:53 Producer – Carl Falk Vocals – Zac Brown True Believer 7 4:48 Vocals, Piano – Chris Martin City Lights 8 6:29 Vocals – Jonas Wallin, Noonie Bao Pure Grinding 9 Co-producer – Albin Nedler, Kristoffer FogelmarkVocals – Earl St. Clair, Kristoffer 2:52 Fogelmark Sunset Jesus 10 4:25 Producer [Additional] – Dhani LennevaldVocals – Sandro Cavazza Can't Catch Me 11 3:59 Vocals – Matisyahu, Wyclef Jean Somewhere In Stockholm 12 3:23 Vocals – Daniel Adams-Ray Trouble 13 2:52 Vocals – Wayne Hector Gonna Love Ya 14 3:35 Producer – Dhani LennevaldVocals – Sandro Cavazza Credits Producer – Arash Pournouri (tracks: 2, 6, 8, 14), Tim Bergling Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0602547573001 Label Code: LC 01846 Matrix / Runout: 06025 475 730-0 01 * 53822358 Made in Germany by EDC A Mastering SID Code: IFPI LV26 Mould SID Code: IFPI 0118 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Stories (14xFile, MP3, none Avicii PRMD none -

Avicii Stories Album Full Download FULL LINK Download Avicii – Stories 2015

avicii stories album full download FULL LINK Download Avicii – Stories 2015. mp3 320 kbps Avicii - Stories Avicii - Stories Download [Free] (Album) Avicii - Stories[Album] 320 kbps Stories Album Leak Download Stories - Avicii Album [Download] Avicii - Stories Leaked Album Avicii - Stories .Zip Download Stories - Avicii .RAR Download Avicii - Stories (2015) download Avicii - Stories has it leaked? Avicii - Stories zip Avicii - Stories rar Avicii - Stories Full Album REVIEW Stories - Avicii HOT. NEW Album Avicii - Stories Album leak Stories where download? Avicii - Stories2015 download Avicii - Stories télécharger Avicii - Stories album mp3 download Avicii - Stories Album leaks Avicii - The Days (feat. Robbie Williams) mp3 download Avicii - The Nights (feat. RAS) mp3 download Avicii - Waiting for Love (feat. Simon Aldred) mp3 download Avicii - Can’t Love You Again (feat. Tom Odell) mp3 download Avicii - For a Better Day (feat. Alex Ebert) mp3 download Avicii - What Would I Change It To (feat. AlunaGeorge) mp3 download Avicii - Heaven (feat. Simon Aldred) | Tim Bergling & Chris Martin mp3 download Avicii - City Lights (feat. Noonie Bao) mp3 download Avicii - Can’t Catch Me (feat. Wyclef Jean & Matisyahu) mp3 download Avicii - Love to Fall (feat. Tom Odell) mp3 download Avicii - No Pleasing a Woman (feat. Billie Joe Armstrong) mp3 download Avicii - Million Miles (feat. LP) mp3 download Avicii - Ten More Days (feat. Bon Jovi) mp3 download Avicii - I Lost My Black Hole (feat. Daniel Adams-Ray) mp3 download Avicii - I’m Still In Love With Your Ghost (feat. Daniel Adams-Ray) mp3 download Avicii - True Believer (feat. Milky Chance) mp3 download Avicii - Touch Me (feat. Audra Mae) mp3 download Avicii - Broken Arrows (feat. -

Poet Nickole Brown Speaks at SOA (5) • Learn the REAL Truth About Thanksgiving (18) • an Update on Fashion and Costume Design (9) • Meet Ms

Applause Volume 17, Number 3 School of the Arts, North Charleston, SC December 2015 soa-applause.com • Check out Wordfest and Yallfest (4) • Poet Nickole Brown speaks at SOA (5) • Learn the REAL truth about Thanksgiving (18) • An update on Fashion and Costume Design (9) • Meet Ms. Godwin, Mr. Morrow, Ms. Baker, and Ms. Scott (10-12) Page 2 Patrons December 2015 SAPPHIRE Rhoda Ascanio & Mark Lazzaro PEARL James and Jennifer Moriarty Colleen Aponte Patrick Burns AMETHYST Curtis Caldwell The Allardice Family Cameron Frye Alan Brehm Alexandra Hepburn Kimberly Zerbst GARNET Fred Horton Sue Bennett TOPAZ Kristina Kerr Debra Benson David Bundy Emily Lanter Brenda Brooks Dr. Shannon Cook Christian Leprettre Bethany Crawford The Doran Family Abby LeRoy Debbie Dekle Sylvia Edwards Ann Marie Fairchild Fiona Lewis Sarah Fitzgerald Kimberly Hood Ari Levine Ginger and Heather Snook Gus and Wendy Molony Collin Lloyd Marcellus Holt Ron and Valerie Paquette Sharon Mahoney Doug Horres Brett Johnson Katy Richardson Zois Manaris Dr. Jane Zazzaro Lassiter and Keith and Dawn Rizer Logan Matthews Dr. Kerry Lassiter Rosie Skylar Moore Rosamond Lawson Tyson Smith Sterling Moore Cynthia Pate Nancy Rickson TURQUOISE Porter Moore Sean Scapellato Tracey Castle Dashaad Noisetle Kevin Short Daniel and Linda Cline Will Schmitt Debbie Summey Jacob Fairchild Bill Smyth David Seim Sylvia Watkins The Gadson Family Hunter Simes Eyamba Williams Beth Webb Hart Anonymous Zack Shirley Kathy Horres Alex Simpson Basil Kerr PERIDOT Nolan Tecklenburg Anonymous Stacy LeBrun Laura Smith Payton Woodall Christine Bednarczyk Kirk Lindgren Thank you Applause Anonymous Antoinette Green Kaci Martin patrons for your Brian Johnson Abbey Reeves generosity! Cheyenne Koth Holly Rizer If you would like to become a Lynn Kramer Sheryl Sabol patron, please e-mail Dr. -

Pure and Alloy Magnesium from Canada and Pure Magnesium from China

Pure and Alloy Magnesium From Canada and Pure Magnesium From China Investigation Nos. 701-TA-309-A-B and 731-TA-696 (Second Review) Publication 3859 July 2006 U.S. International Trade Commission COMMISSIONERS Daniel R. Pearson, Chairman Shara L. Aranoff, Vice Chairman Jennifer A. Hillman Stephen Koplan Deanna Tanner Okun Charlotte R. Lane Robert A. Rogowsky Director of Operations Staff assigned Fred Fischer, Investigator Jeremy Wise, Investigator Vincent DeSapio, Industry Analyst Robert Hughes, Economist Ioana Mic, Economist Charles Yost, Accountant Jonathan Engler, Attorney Peter Sultan, Attorney Steven Hudgens, Statistician George Deyman, Supervisory Investigator Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov Pure and Alloy Magnesium From Canada and Pure Magnesium From China Investigation Nos. 701-TA-309-A-B and 731-TA-696 (Second Review) Publication 3859 July 2006 Inv. No. 701-TA-309-A-B and 731-TA-696 (Second Review) Pure and Alloy Magnesium CONTENTS Page Determinations and Views of the Commission ...................................... 1 Determinations ............................................................. 1 Views of the Commission..................................................... 3 Views of Chairman Pearson and Commissioners Okun and Lane ................... 6 Views of Vice Chairman Aranoff and Commissioners Hillman and Koplan ........... 34 Part I: Introduction and overview -

America's Cup Sailing

America’s Cup Sailing: Biomechanics and conditioning for performance in grinding Simon Pearson BSc & MHSc (Hons) A thesis submitted to the Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Attestation of authorship ......................................................................................................... 10 Candidate contributions to co-authored papers ................................................................... 11 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 12 Ethical approval .......................................................................................................... 12 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Research publications resulting from this doctoral thesis .................................................. 14 Chapter 1 ................................................................................................................................... 17 Introduction and rationalisation (Preface) ............................................................................. 17 Background ................................................................................................................. 17 Structure ..................................................................................................................... 17 Chapter -

“Pure Grinding” Och “For a Better Day”

2015-09-03 13:46 CEST AVICII GÖR SIN REGI-DEBUT MED VIDEOS TILL SINGLARNA “PURE GRINDING” OCH “FOR A BETTER DAY” Med två amerikanska Grammy nomineringar och pris på American Music Awards gör superstjärnan Avicii sin regidebut idag med världspremiären för två videos till “For A Better Day” och “Pure Grinding,” den nya dubbel-singeln från hans kommande album STORIES, som släpps 2 oktober på PRMD/Universal. “For A Better Day” http://Avicii.lnk.to/FABDYoutube / http://Avicii.lnk.to/FABDVevo “Pure Grinding” http://Avicii.lnk.to/PureGrindingYoutube / http://Avicii.lnk.to/PureGrindingVevo “Alla låtar innehåller en story som jag ville berätta,” säger Avicii, och fortsätter sitt berättande med sina två filmiska videos. Båda är regisserade av Levan Tsikurishvili och Tim Bergling och spelades in i Ungern under sommaren. Båda är actionspäckade med underliggande sociala teman. I videon till “For A Better Day” medverkar skådespelaren Krister Henriksson, mest känd för huvudrollen i TV-serien “Wallander”. Videon belyser trafficking som är en internationell tragedi. Avicii, säger att han vill att hans musik ska ha en mening utöver förmågan att underhålla. “Löftet om ett bättre liv någon annanstans gör familjer och barn till fångar hos några av de mest avskyvärda människorna i världen. Jag hoppas kunna bidra till att lyfta frågan och skapa debatt, speciellt nu när ofantliga mängder människor är på flykt från krigshärjade länder.” Besök UNICEF.org för mer information. Till "Pure Grinding," som Billboard magazine kallar “a refreshing slice of swing funk whose guitar licks and sax lines fit seamlessly into the producer's tasteful trap-inspired beats,” kommer en video som är en rolig och actionfylld gangster-saga som påminner om en modern Sergio Leone-western. -

Music Library

TITLE ARTIST Anywhere 112 ft Lil Z Cupid 112 Hot & Wet 112 ft Ludacris Line Dance Mix 112 Na Na Na 112 ft Supercat Only You 112 ft Notorious B.I.G. Tonight 112 U Already Know 112 What If 112 All I Want 702 Get It Together 702 Where My Girls At 702 Hold On Loosely .38 Special 96 Tears ? & The Mysterians Everything Good Is Bad 100 Proof (Aged In Soul) Somebody's Been Sleeping In My Bed 100 Proof Aged In Soul Envy Me 147Calboy 2 Dollar Bill 2 Chainz ft. Lil Wayne & E-40 Birthday Song 2 Chainz ft Kanye West Bounce 2 Chainz ft Lil Wayne Crack 2 Chainz Fork 2 Chainz I'm Different 2 Chainz Money In The Way 2 Chainz No Lie 2 Chainz ft Drake Proud 2 Chainz ft YG n Offset U Da Realest 2 Chainz Watch Out 2 Chainz Where U Been 2 Chainz Wiggle It 2 In A Room Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew Me So Horny 2 Live Crew Pop That Coochie 2 Live Crew We Want Some P***y 2 Live Crew A Lot 21 Savage ft. J. Cole All About U 2Pac ft. Nate Dogg & Top Dogg All Eyez On Me 2Pac Baby Don't Cry 2Pac & The Outlawz Better Dayz 2Pac Brenda's Got A Baby 2Pac California Love 2Pac ft. Dr Dre Can't C Me 2pac ft George Clinton Changes 2Pac Cradle To The Grave 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Do For Love 2Pac Gangsta Party 2Pac Hail Mary 2Pac ft The Outlawz High Till I Die 2Pac Hit 'Em Up 2Pac ft Outlawz How Do U Want It 2Pac ft K-Ci n JoJo How Long Will They Mourn Me 2Pac I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac ft Danny Boy I Get Around 2Pac ft Digital Underground If I Die 2Nite Tupac It's A Gangsta Party (Remix) 2Pac ft Snoop Dogg Keep Ya Head Up 2Pac Last Muthaf***a Breathin' Tupac My Block 2Pac Never Had A Friend Like Me Tupac Only God Can Judge Me Tupac Picture Me Rollin' Tupac Run Tha Streetz Tupac Skandalouz 2Pac Smile Tupac ft Scarface So Many Tears 2Pac Street Fame 2Pac To Live & Die In L.A. -

Printer Access for the Modern Age All Students to Have Access to On-Campus 3-D Printers PAGE 7 Another 3D Printer

Wednesday, September 2, 2015 Volume 124, No. 17 • collegian.com THE STRIP 3D Printing is now more available to all students at CSU. Now that we can all use it, here are some things we would make: COLLEGIAN FILE PHOTO Plates. So that you never have to do the dishes ever again. #Unsustainable Printer access for the modern age All students to have access to on-campus 3-D printers PAGE 7 Another 3D Printer. It’s like being the a**hole who asks the genie for more wishes. OPINION ENTERTAINMENT NEWS Confl ict HeyDay ASCSU A segway... Colorado Never mind, a resolution Feature bunch of segways Tips to avoid Representative for the people Chic boutique Jeni Arndt to who hand out the drama in your for all your Collegian. They will relationships this speak in senate chase you. They will household needs chamber fi nd you. You will semester opens in FoCO take a paper. Wednesday PAGE 4 PAGE 12 PAGE 2 2 Wednesday, September 2, 2015 | The Rocky Mountain Collegian collegian.com ON THE OVAL FORT COLLINS FOCUS OFF THE OVAL Colorado Not enough Representative evidence to charge Jeni Arndt to speak former University at ASCSU Senate of Central Florida Wednesday student in rape case Members of the Associat- ORLANDO, Fla. _ A ed Students of Colorado State former University of Central University are encouraging Florida student will not be student input on city policies by charged with a crime after bringing local politicians to the he was accused of raping a CSU campus. student he met at a Sigma Nu Colorado Representative fraternity party. -

Beautiful Heartbeat Avicii Free Mp3 Download Beautiful Heartbeat Avicii Free Mp3 Download

beautiful heartbeat avicii free mp3 download Beautiful heartbeat avicii free mp3 download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67e2d136edcbcb08 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. VA — Pacha Ibiza Summer 2016 CD1. MP3 is a digital audio format without digital rights management (DRM) technology. Because our MP3s have no DRM, you can play it on any device that supports MP3, even on your iPod! KBPS stands for kilobits per second and the number of KBPS represents the audio quality of the MP3s. Here's the range of quality: 128 kbps = good, 192 kbps = great, 256 kbps = awesome and 320 kbps = perfect. Customer reviews (1) Write a review. Be warned: Continuous mix. iTunes compatible. Listen on your iPhone. 24/7 support. Burn CDs' Your own albums. Welcome bonus. More free music. About. Statistics. Artists: 241647 Albums: 703373 Tracks: 7922655 Storage: 61381 GB. Legend Series – This Is Avicii. Legend! This time, we are talking about the one and only AVICII. -

Dance Charts Monat 12 / Jahr 2015

Dance Charts Monat 12 / Jahr 2015 Pos. VM Interpret Titel Label Punkte +/- Peak Wo 1 1 FELIX JAEHN FEAT. POLINA BOOK OF LOVE UNIVERSAL 5005 0 1 4 2 94 SIGALA SWEET LOVIN' SONY 4187 +92 2 2 3 2 ROBIN SCHULZ FEAT. FRANCESCO YATES SUGAR WARNER 4077 -1 1 6 4 123 ROBIN SCHULZ & J.U.D.G.E. SHOW ME LOVE TONSPIEL 4007 +119 4 2 5 3 CALVIN HARRIS & DISCIPLES HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE SONY 3270 -2 2 6 6 5 SIGALA EASY LOVE SONY 3058 -1 5 4 7 28 DAVID GUETTA FEAT. SIA & FETTY WAP BANG MY HEAD WARNER 2705 +21 7 2 8 15 GLASPERLENSPIEL GEILES LEBEN UNIVERSAL 2588 +7 8 4 9 8 ROCKSTROH FEAT. MICHAEL FRIEDA SOMMERSPROSSEN ROCKSTROH MUSIC 2541 -1 8 3 10 4 OMI HULA HOOP ULTRA / SONY 2385 -6 4 4 11 54 SDP FEAT. ADEL TAWIL ICH WILL NUR DASS DU WEIßT [B-CASE UNIVERSAL 2286 +43 11 2 REMIX] 12 12 SEAN FINN CAN YOU FEEL IT NITRON MUSIC 2052 0 12 3 13 135 ANDREW SPENCER & BROOKLYN BOUNCE DON'T STOP MENTAL MADNESS RECORDS 1902 +122 13 2 14 9 HARDWELL & ARMIN VAN BUUREN OFF THE HOOK REVEALED / ARMADA 1825 -5 9 4 15 10 LOST FREQUENCIES FEAT. JANIECK DEVY REALITY ARMADA / KONTOR 1559 -5 2 7 16 21 STEREOACT FEAT. KERSTIN OTT DIE IMMER LACHT TOKA BEATZ 1521 +5 16 5 17 JASON PARKER FEAT. JOHNNY D NIGHTSHIFT SOUNDS UNITED 1401 0 17 1 18 65 DJ KATCH FEAT. GREG NICE, DJ KOOL & THE HORNS WARNER 1395 +47 18 2 DEBORAH LEE 19 DJ TONKA SHE KNOWS YOU (UPDATE) WARNER 1383 0 19 1 20 7 FAITHLESS INSOMNIA 2.0 (AVICII REMIX) MUSICAL FREEDOM 1378 -13 3 5 21 58 NAXWELL LIVING ON VIDEO SOUNDS UNITED 1376 +37 21 2 22 78 FITCH N STILO WENN ICH ANKOMM ROCKSTROH MUSIC 1336 +56 22 2 23 16 BEATA MARIA MAGDALENA PASSION & DIVINE 1322 -7 16 3 24 84 PRINCE AMAHO FREEDOM POPYA! / PULSIVE MEDIA 1285 +60 24 2 25 27 DJ COMBO FEAT. -

Ellsworth American : March 31, 1865

office in peters- block. teIims_$2,00 PER YEAR in advance. DEVOTED TO POLITICS, LITERATURE -A-ISTD GEISTER-AL NEWS. * MARCH 1865. VOL. XI::: TO. 11 BY SAWYER & BURR. ELLSWORTH, MAINE, FRIDAY, 31, • _____ Little Starlight. Court'/'’ mud I laughing, and turning to fly yourse’f. Yah, yah! Use a awlul Anil as we went away, I saw his DUS FOR SALE. the cuts, I is.” taclie tremble perceptibly. Cauls. soon after the first of those terri- Major. It wa^ were §tt$inf$!3 on and “1 do not know,” was the a briefer with Star- There three members of fllUE subscriber koeps constantly hand, ble Wilderness battles of last that really reply. Upon acquaintance regular A. lor sale, spring “Ask the if he will and I should have smiled at the serio- C who died ibe death in that DAVIS A IOBD, God Save our President. little made his monkey fight light, Company Starlight appcaranccamong comic manner these sentiments but I think not one of wholesale and retail dealers in Oakum, which side he favors.” in which skirmish, them Tar, Pilch, uo. of were enunciated but as it was. I shud- was mourned with a sineerer STEEL » and a good stock BT FRANCIS DE I1AES JANVIER. I put the ; deeper, HARDWARE, IRON AND. Now have you any idea who little Star- question. Mast “Do Union all the time, snore!” was dered at the of which sorrow than was Little One 41 N’o. 4 Main Street, Ki.Lawor.Tn. Hemp and Manilla Cordage, Hoops, I. was? from his ro- intensity passion Starlight.