The Small World of a Big Western

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syndication's Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults

Syndication’s Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults An E-Score Analysis of Awareness and Affinity Among Adults 18-34 March 2007 BEHAVIORAL EMOTIONAL “Engagement happens inside the consumer” Joseph Plummer, Ph.D. Chief Research Officer The ARF Young Adults Have An Emotional Bond With The Stars Of Syndication’s Sitcoms • Personalities connect with their audience • Sitcoms evoke a wide range of emotions • Positive emotions make for positive associations 3 SNTA Partnered With E-Score To Measure Viewers’ Emotional Bonds • 3,000+ celebrity database • 1,100 respondents per celebrity • 46 personality attributes • Conducted weekly • Fielded in 2006 and 2007 • Key engagement attributes • Awareness • Affinity • This Report: A18-34 segment, stars of syndicated sitcoms 4 Syndication’s Off-Network Stars: Beloved Household Names Awareness Personality Index Jennifer A niston 390 Courtney Cox-Arquette 344 Sarah Jessica Parker 339 Lisa Kudrow 311 Ashton Kutcher 297 Debra Messing 294 Bernie Mac 287 Matt LeBlanc 266 Ray Romano 262 Damon Wayans 260 Matthew Perry 255 Dav id Schwimme r 239 Ke ls ey Gr amme r 229 Jim Belushi 223 Wilmer Valderrama 205 Kim Cattrall 197 Megan Mullally 183 Doris Roberts 178 Brad Garrett 175 Peter Boyle 174 Zach Braff 161 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. Eric McCormack 160 Index of Average Female/Male Performer: Awareness, A18-34 Courtney Thorne-Smith 157 Mila Kunis 156 5 Patricia Heaton 153 Measures of Viewer Affinity • Identify with • Trustworthy • Stylish 6 Young Adult Viewers: Identify With Syndication’s Sitcom Stars Ident ify Personality Index Zach Braff 242 Danny Masterson 227 Topher Grace 205 Debra Messing 184 Bernie Mac 174 Matthew Perry 169 Courtney Cox-Arquette 163 Jane Kaczmarek 163 Jim Belushi 161 Peter Boyle 158 Matt LeBlanc 156 Tisha Campbell-Martin 150 Megan Mullally 149 Jennifer Aniston 145 Brad Garrett 140 Ray Romano 137 Laura Prepon 136 Patricia Heaton 131 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. -

Everybody Loves Raymond” Let’S Shmues--Chat

THANKSGIVING WITH THE CAST OF “EVERYBODY LOVES RAYMOND” LET’S SHMUES--CHAT The Yiddish word for “turkey” is “indik.” “Dankbar” is the Yiddish word for “thankful.” By MARJORIE GOTTLIEB WOLFE 46 “milyon” turkeys are eaten each Thanksgiving. Turkey consumption has increased 104% since 1970. And 88% of Americans surveyed by the National Turkey Federation eat turkey on this holiday. Marie Barone (Doris Roberts) is devoted to making sure her boys are well-fed. She gets her adult children back with food. It’s like a culinary hostage trade-off. Marie wants Debra, her daughter-in-law, to be a better cook. She calls her “cooking-challenged” and thinks that she should live directly opposite Zabar’s. Marie want the children to have better food. She says, “A mother’s love for her sons is a lot like a dog’s piercing bark: protective, loyal, and impossible to ignore. Many episodes of “Everybody Loves Raymond” dealt with Thanksgiving. Grab a #2 pencil and see if you can identify which of the following story lines is real or fabricated. Good luck. EPISODE 1. Thanksgiving has arrived. Marie is on a “diete.” She has just returned from a residential treatment facility for weight (“vog”) loss at Duke University in North Carolina. It was an expensive (“tayer”) program. The lockdown began: Low-Fat, No-Sugar (“tsuker”), No Taste foods, and 750 calories a day. (That’s the equivalent of a slice of chocolate cake.) One woman in the program sent herself “Candygrams” each week (“vokh”). Doris eats very little (“a bisl”) at the Thanksgiving table, but as she is preparing to leave Debra’s house, she asks for a little leftover turkey and apple (“epl”) chutney. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’S Impact on the Western

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’s Impact on the Western Jacob A. Williams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Claudia Gorbman E. Joseph Sharkey Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Section I The Anti-Hero: Newborn or Reborn Hero? 4 Section II A Greek Tradition: Violence as Catharsis 11 Section III The Theseus Theory 21 Section IV A Modern Greek Tale: The Outlaw Josey Wales 31 Section V The Euripides Effect: Bringing the Audience on Stage 40 Section VI The Importance of the Western Myth 47 Section VII Conclusion: The Immortality of the Western 49 Bibliography 53 Sources Cited 62 i Dedication To my wife and children, whom I cherish every day: To Brandy, for always being the one person I can always count on, and for supporting me through this entire process. You are my love and my life. I couldn’t have done any of this without you. To Andrew, for always being so responsible, being an awesome big brother to your siblings, and always helping me whenever I need you. You are a good son, and I am proud of the man you are becoming. To Tristan, for always being my best friend, and my son. You never cease to amaze and inspire me. Your creativity exceeds my own. To Gracie, for being my happy “Pretty Princess.” Thank you for allowing me to see the world through the eyes of a nature-loving little girl. -

{PDF EPUB} the Elephants by Georges Blond the Elephants by Georges Blond

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Elephants by Georges Blond The Elephants by Georges Blond. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 6607bc654d604edf • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Sondra Locke: a charismatic performer defined by a toxic relationship with Clint Eastwood. S ondra Locke was an actor, producer, director and talented singer. But it was her destiny to be linked forever with Clint Eastwood, whose partner she was from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s. She was a sexy, charismatic performer with a tough, lean look who starred alongside Eastwood in hit movies like The Outlaw Josey Wales, The Gauntlet, Every Which Way But Loose (in which she sang her own songs — also for the sequel Any Which Way You Can) and Bronco Billy. But the pair became trapped in one of the most notoriously toxic relationships in Hollywood history, an ugly, messy and abusive overlap of the personal and professional — a case of love gone sour and mentorship gone terribly wrong. -

'Pale Rider' Is Clint Eastwood's First Western Film Since He Starred in and Directed "The Outlaw Josey Wales" in 1976

'Pale Rider' is Clint Eastwood's first Western film since he starred in and directed "The Outlaw Josey Wales" in 1976. Eastwood plays a nameless stranger who rides into the gold rush town of LaHood, California and comes to the aid of a group of independent gold prospectors who are being threatened by the LaHood mining corporation. The independent miners hold claims to a region called Carbon Canyon, the last of the potentially ore-laden areas in the county. Coy LaHood wants to dredge Carbon Canyon and needs the independent miners out LaHood hires the county marshal, a gunman named Stockburn with six deputies, to get the job done. What neither LaHood nor Stockburn could possibly have taken into consideration is the appearance of the enigmatic horseman and the fate awaiting them. This study guide attempts to place 'Pale Rider' within the Western genre and also within the canon of Eastwood's films. We would suggest that the work on Film genre and advertising are completed before students see 'Pale Rider'. FILM GENRE The word "genre" might well be unfamiliar to you. It is a French word which means "type" and so when we talk of film genre we mean type of film. The western is one particular genre which we will be looking at in detail in this study guide. What other types of genre are there in film? Horror is one. Task One Write a list of all the different film genres that you can think of. When you have done this, try to write a list of genres that you might find in literature. -

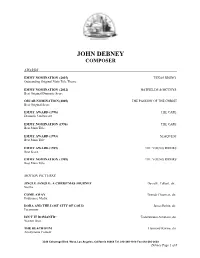

John Debney Composer

JOHN DEBNEY COMPOSER AWARDS EMMY NOMINATION (2015) TEXAS RISING Outstanding Original Main Title Theme EMMY NOMINATION (2012) HATFIELDS & MCCOYS Best Original Dramatic Score OSCAR NOMINATION (2005) THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST Best Original Score EMMY AWARD (1996) THE CAPE Dramatic Underscore EMMY NOMINATION (1996) THE CAPE Best Main Title EMMY AWARD (1993) SEAQUEST Best Main Title EMMY AWARD (1989) THE YOUNG RIDERS Best Score EMMY NOMINATION (1989) THE YOUNG RIDERS Best Main Title MOTION PICTURES JINGLE JANGLE: A CHRISTMAS JOURNEY David E. Talbert, dir. Netflix COME AWAY Brenda Chapman, dir. Endurance Media DORA AND THE LOST CITY OF GOLD James Bobin, dir. Paramount ISN’T IT ROMANTIC Todd Strauss-Schulson, dir. Warner Bros. THE BEACH BUM Harmony Korine, dir. Anonymous Content 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Debney Page 1 of 6 JOHN DEBNEY COMPOSER MOTION PICTURES (continued) BRIAN BANKS Tom Shadyac, dir. Gidden Media THE GREATEST SHOWMAN Michael Gracey, dir. Fox BEIRUT Brad Anderson, dir. Warner Bros. HOME AGAIN Hallie Meyers-Shyer, dir. Open Road Films THE JUNGLE BOOK Jon Favreau, dir. Disney ICE AGE: COLLISION COURSE Mike Thurmeier, dir. Fox MOTHER’S DAY Garry Marshall, dir. Open Road Films LEAGUE OF GODS Koan Hui, dir. Asia Releasing THE YOUNG MESSIAH Cyrus Nowrasteh, dir. Focus Features THE SPONGEBOB MOVIE: SPONGE OUT OF WATER Paul Tibbitt, dir. Paramount Pictures THE COBBLER Thomas McCarthy, dir. Voltage Pictures DRAFT DAY Ivan Reitman, dir. Summit Entertainment WALK OF SHAME Steven Brill, dir. Lakeshore Entertainment ELIZA GRAVES Brad Anderson, dir. Millennium Films CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR (theme) Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum, dir. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Everybody Loves Christmas! Free

FREE EVERYBODY LOVES CHRISTMAS! PDF Andrew Davenport | 16 pages | 09 Sep 2013 | BBC Children's Books | 9781405908641 | English | London, United Kingdom "Everybody Loves Raymond" All I Want for Christmas (TV Episode ) - IMDb From Coraline to ParaNorman check out some of our favorite family-friendly movie picks to watch this Halloween. See the full gallery. All Ray wants for Christmas is a little loving from his wife, and he's willing to try anything and everything to have his holiday wish come true. After having planned a time and day to make love in advance, Debra cancels it. Ray wonders why Debra is never "in Everybody Loves Christmas! mood". While working at Giants Stadium, Ray complains to his buddy Andy. But Andy, being single, doesn't have any advice. So they both ask a co-worker Erin for advice Ray then tries to use Erin's advice Everybody Loves Christmas! Debra. But by Everybody Loves Christmas! time Debra is finally in the mood, it just so happens to be Christmas morning. So instead of having sex, they have to put up with Everybody Loves Christmas! family for the holiday. Looking for something to watch? Choose an adventure below and discover your next favorite movie or TV show. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Full Cast and Crew. Release Dates. Official Sites. Company Credits. Technical Specs. Plot Summary. Plot Keywords. Parents Guide. External Sites. User Reviews. User Ratings. External Reviews. Metacritic Reviews. Photo Gallery. Trailers and Videos. Crazy Credits. Alternate Versions. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Widescreen Weekend 2010 Brochure (PDF)

52 widescreen weekend widescreen weekend 53 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (70MM) REMASTERING A WIDESCREEN CLASSIC: Saturday 27 March, Pictureville Cinema WINDJAMMER GETS A MAJOR FACELIFT Dir. Stanley Kubrick GB/USA 1968 149 mins plus intermission (U) Saturday 27 March, Pictureville Cinema WIDESCREEN Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, Leonard Rossiter, Ed Presented by David Strohmaier and Randy Gitsch Bishop and Douglas Rain as Hal The producer and director team behind Cinerama Adventure offer WEEKEND During the stone age, a mysterious black monolith of alien origination a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at how the Cinemiracle epic, influences the birth of intelligence amongst mankind. Thousands Now in its 17th year, the Widescreen Weekend Windjammer, was restored for High Definition. Several new and of years later scientists discover the monolith hidden on the moon continues to welcome all those fans of large format and innovative software restoration techniques were employed and the re- which subsequently lures them on a dangerous mission to Mars... widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, mastering and preservation process has been documented in HD video. Regarded as one of the milestones in science-fiction filmmaking, Cinerama and IMAX – and presents an array of past A brief question and answer session will follow this event. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey not only fascinated audiences classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. This event is enerously sponsored by Cinerama, Inc., all around the world but also left many puzzled during its initial A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. release. More than four decades later it has lost none of its impact. -

Tv Land Loves “Raymond”

TV LAND LOVES “RAYMOND” TV Land PRIME Locks Up The Exclusive Primetime Broadcast Rights For “Everybody Loves Raymond” Additional Acquisitions for 2010 Include “Boston Legal,” “Home Improvement” and “The Nanny” New York, NY, October 6, 2009 – TV Land has landed the primetime broadcast rights for the Emmy® Award-winning comedy, “Everybody Loves Raymond,” from CBS Television Distribution beginning June 2010, it was announced today by Larry W. Jones, president, TV Land. The winner of 15 Emmy® Awards, “Everybody Loves Raymond” ran in primetime for nine seasons, totaling 212 episodes and will premiere in TV Land PRIME, the network’s primetime programming block designed to appeal to the attitudes, life stage and interests of people in their 40s. Additionally, the network announced three other new acquisitions to hit the airwaves in 2010: “Boston Legal,” “Home Improvement” and “The Nanny.” “‘Everybody Loves Raymond’ is one of TV’s quintessential comedies, and we are thrilled to have the Barones join the TV Land family,” stated Jones. “‘Raymond,’ ‘Boston Legal,’ ‘Home Improvement’ and ‘The Nanny’ all speak to our audience of forty-somethings in different ways. From an office-based dramedy to family-oriented comedies, the themes and relationships in these series continue to make us laugh.” These four acquisitions represent a continued commitment to build TV Land PRIME, the network’s primetime programming destination dedicated to 40-somethings – a vibrant group with unmatched purchasing power and living in the most dynamic stage of their lives with relationships at work, with family and with friends all thriving. All of the programming in TV Land PRIME is hand-picked to appeal to the attitudes, life stage and interests of this important demo.