Studying Smartphone Usage: Lessons from a Four-Month Field Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Tertainment and Value to the Low SES Users

Tales of 34 iPhone Users: How they change and why they are different Ahmad Rahmati1, Clayton Shepard1, Chad Tossell2, Mian Dong1, Zhen Wang1, Lin Zhong1, Philip Kortum2 1 Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, 2 Department of Psychology Technical Report TR-2011-0624, Rice University, Houston, TX Abstract trolled demographics and carefully designed interaction with them over the course of the study. Instead of trying to We present results from a longitudinal study of 34 iPh- represent a broad demography of smartphone users, we one 3GS users, called LiveLab. LiveLab collected unprece- chose to focus on a very specific user population, college dented usage data through an in-device, programmable students of similar age, but with different socioeconomic logger and several structured interviews with the partici- backgrounds. This strict selection allows us to gain deep pants throughout the study. We have four objectives in insight in to the behaviour of this population, as well as writing this paper: (i) share the findings with the research discover the unadulterated influence of socioeconomic sta- community; (ii) provide insights guiding the design of tus on usage. Our unique access to the participants further smartphone systems and applications; (iii) demonstrate the allows us to gain otherwise impossible insights into the power of prudently designed longitudinal field studies and data collected by the in-device logger. the power of advanced research methods; and (iv) raise important questions that the research community can help Third, LiveLab is the first publicly reported study of answer in a collaborative, multidisciplinary manner. iPhone users with in-device usage logging. Prior work has studied usage of Android and Windows Mobile based We show how the smartphone usage changes over the smartphones with in-device logging. -

Mobiliųjų Telefonų Modeliai, Kuriems Tinka Ši Programinė Įranga

Mobiliųjų telefonų modeliai, kuriems tinka ši programinė įranga Telefonai su BlackBerry operacinė sistema 1. Alltel BlackBerry 7250 2. Alltel BlackBerry 8703e 3. Sprint BlackBerry Curve 8530 4. Sprint BlackBerry Pearl 8130 5. Alltel BlackBerry 7130 6. Alltel BlackBerry 8703e 7. Alltel BlackBerry 8830 8. Alltel BlackBerry Curve 8330 9. Alltel BlackBerry Curve 8530 10. Alltel BlackBerry Pearl 8130 11. Alltel BlackBerry Tour 9630 12. Alltel Pearl Flip 8230 13. AT&T BlackBerry 7130c 14. AT&T BlackBerry 7290 15. AT&T BlackBerry 8520 16. AT&T BlackBerry 8700c 17. AT&T BlackBerry 8800 18. AT&T BlackBerry 8820 19. AT&T BlackBerry Bold 9000 20. AT&T BlackBerry Bold 9700 21. AT&T BlackBerry Curve 22. AT&T BlackBerry Curve 8310 23. AT&T BlackBerry Curve 8320 24. AT&T BlackBerry Curve 8900 25. AT&T BlackBerry Pearl 26. AT&T BlackBerry Pearl 8110 27. AT&T BlackBerry Pearl 8120 28. BlackBerry 5810 29. BlackBerry 5820 30. BlackBerry 6210 31. BlackBerry 6220 32. BlackBerry 6230 33. BlackBerry 6280 34. BlackBerry 6510 35. BlackBerry 6710 36. BlackBerry 6720 37. BlackBerry 6750 38. BlackBerry 7100g 39. BlackBerry 7100i 40. BlackBerry 7100r 41. BlackBerry 7100t 42. BlackBerry 7100v 43. BlackBerry 7100x 1 44. BlackBerry 7105t 45. BlackBerry 7130c 46. BlackBerry 7130e 47. BlackBerry 7130g 48. BlackBerry 7130v 49. BlackBerry 7210 50. BlackBerry 7230 51. BlackBerry 7250 52. BlackBerry 7270 53. BlackBerry 7280 54. BlackBerry 7290 55. BlackBerry 7510 56. BlackBerry 7520 57. BlackBerry 7730 58. BlackBerry 7750 59. BlackBerry 7780 60. BlackBerry 8700c 61. BlackBerry 8700f 62. BlackBerry 8700g 63. BlackBerry 8700r 64. -

Understanding Human-Battery Interaction on Mobile Phones

Understanding Human-Battery Interaction on Mobile Phones Ahmad Rahmati, Angela Qian, and Lin Zhong Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering Rice University, Houston, TX 77005 {rahmati, qangela, lzhong}@rice.edu ABSTRACT human users deal with limited battery lifetime, which we call Mobile phone users have to deal with limited battery lifetime human-battery interaction (HBI). Human-battery interaction is a through a reciprocal process we call human-battery interaction reciprocal process. On one hand, modern mobile phones provide (HBI). We conducted three user studies in order to understand users with indicators of the battery charge level, as well as user HBI and discover the problems in existing mobile phone designs. interfaces for changing power-saving settings, such as display The studies include a large-scale international survey, a one- brightness reduction. We refer to these indicators and user month field data collection including quantitative battery logging interfaces collectively as the battery interface. On the other hand, and qualitative inquiries from ten mobile phone users, and human users can react to the dropping battery charge level by structured interviews with twenty additional mobile phone users. changing the power-saving settings, altering usage patterns, and We evaluated various aspects of HBI, including charging charging the phone. behavior, battery indicators, user interfaces for power-saving Understanding HBI will provide valuable insight into the settings, user knowledge, and user reaction. We find that mobile effectiveness of the battery interface, and how mobile users deal phone users can be categorized into two types regarding HBI and with limited battery lifetime, prioritize and make tradeoffs. often have inadequate knowledge regarding phone power Knowledge regarding HBI will essentially help design better characteristics. -

RIFF Box JTAG - Original

GSM-Support ul. Bitschana 2/38, 31-420 Kraków, Poland mobile +48 608107455, NIP PL9451852164 REGON: 120203925 www.gsm-support.net RIFF Box JTAG - original RIFF Box JTAG is a new device from Rocker Team. There are no other device with so many complex functions supported. As always, Rocker team released something unique and outstanding. The devices suits most of user needs, although is aimed at advanced developers who need to debug their own embedded code. (Or reverse someone’s else ). Unique scripting support, GDB Server for IDA real time debugging, Trace32 scripts compatibility and high quality hardware will be on Your service. Our R&D Team is ready to serve our valued customers as well as our tech support staff. RIFF JTAG firmware supports following features at the moment: ARM7/ARM9/ARM11 PXA3xx, PXA270, Cortex-A8, OMAP850, Cortex-A9 Dual cores support; Multiple devices on JTAG chain are supported, thus TAP number selection is available; Any custom voltage level selection from range ~1.4V to 3.3V TCK/Adaptive clocking selection Halt core (NRST is not changed) Reset core (NRST is applied before halt) Direct Read memory (by 8/16/32-bit bytes/half-words/words) Direct Write memory (by 8/16/32-bit bytes/half-words/words) Access to the control registers of ARM core (coprocessor 15) Program code breakpoints Run core Custom scripting and DCC loader support (trace32 compatible) Custom GDB Server Available I/O pins detection !Unique feature offered only by RIFF JTAG Currently supported memory controllers are: OneNAND Memory (connected directly -

Point&Connect: Intention-Based Device Pairing for Mobile Phone Users

Point&Connect: Intention-based Device Pairing for Mobile Phone Users Chunyi Peng1, Guobin Shen1, Yongguang Zhang1, Songwu Lu2 1Microsoft Research Asia, Beijing, 100190, China 2Univ. of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA {chunyip,jackysh,ygz}@microsoft.com, [email protected] ABSTRACT Point&Connect (P&C) offers an intuitive and resilient device pair- ing solution on standard mobile phones. Its operation follows the simple sequence of point-and-connect: when a user plans to pair her mobile phone with another device nearby, she makes a simple hand gesture that points her phone towards the intended target. The system will capture the user’s gesture, understand the target selec- tion intention, and complete the device pairing. P&C is intention- based, intuitive, and reduces user efforts in device pairing. The Figure 1: Motivating scenario main technical challenge is to come up with a simple system tech- nique to effectively capture and understand the intention of the user, and pick the right device among many others nearby. It should fur- 1. INTRODUCTION ther work on any mobile phones or small devices without relying In recent years, mobile phones have become increasingly popu- on infrastructure or special hardware. P&C meets this challenge lar. This has led to many new applications such as file swapping, with a novel collaborative scheme to measure maximum distance music sharing, and collaborative gaming, where nearby users en- change based on acoustic signals. Using only a speaker and a mi- gage in spontaneous wireless data communications through their crophone, P&C can be implemented solely in user-level software mobile phone Bluetooth or WiFi interfaces. -

Field Test Modes

NOT E: Signal strength, measured in decibels (dB), is expressed as a negative number. On certain phones, the number may show as positive in test mode. In such cases, convert it to negative. For example, 60 dB is actually -60 dB. The higher the number, the stronger the signal. Thus, -60 dB is a stronger signal than -75 dB. Contact Repeaterstore Technical Support Department at 800-761-3041 if you have questions, or if you need assistance with the test mode of your cell phone. FIELD TEST MODES Apple iPhone Kyocera 2035, 2135, 2235, 2255, 5135 In phone mode dial *3001#12345#* then press CALL. Press 111111 (six ones). Select OPTIONS and press MENU (the upper right- The Field Test Screen will appear. Select “Cell Information.” hand star button) or OK to select it. Select DEBUG and press MENU or OK. Signal Strength is on the top line after RX-. Frequency follows FQ and is based Enter field debug code, 111111 or 000000 (six ones or zeros) or 040793. on the channel number (i.e. 100-200 is 800 MHz and 500-700 is 1900MHz). Scroll down to DEBUG SCREEN and press MENU or OK. Scroll to BASIC and The top line displays information about the tower you are using. The lines press MENU or OK. The signal strength is the last number on the 1 st line. below display info about your neighboring towers. To exit the field test, select CLOSE and press MENU or OK. Kyocera K9, 47, 414, 424, 434, 484, 494, 1135, 2325, 2345, 3225 Audiovox 8615 Press 111111 (six ones). -

Context-Sensitive Energy-Efficient Wireless Data Transfer

Context-for-Wireless: Context-Sensitive Energy-Efficient Wireless Data Transfer Ahmad Rahmati and Lin Zhong Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering Rice University, Houston, TX 77005 {rahmati, lzhong}@rice.edu ABSTRACT Keywords Ubiquitous connectivity on mobile devices will enable numerous Energy-efficient wireless, multiple wireless interfaces, context- new applications in healthcare and multimedia. We set out to for-wireless check how close we are towards ubiquitous connectivity in our daily life. The findings from our recent field-collected data from 1. INTRODUCTION an urban university population show that while network Emerging mobile applications in healthcare and multimedia availability is decent, the energy cost of network interfaces poses demand ubiquitously available wireless network connectivity. a great challenge. Based on our findings, we propose to leverage Despite of the wide deployment of 2.5G & 3G cellular networks the complementary strength of Wi-Fi and cellular networks by and an increasing number of Wi-Fi hot-spots, it is still an open choosing wireless interfaces for data transfers based on network question how close we are towards achieving ubiquitous condition estimation. We show that an ideal selection policy can connectivity in our everyday life. In this work, we present our more than double the battery lifetime of a commercial mobile findings from our recent field collected data about wireless phone, and the improvement varies with data transfer patterns and network availability and energy cost, and investigate context- Wi-Fi availability. based Wi-Fi estimation for energy-efficient wireless data transfer. We formulate the selection of wireless interfaces as a As a reality check and case study, we gathered field data statistical decision problem. -

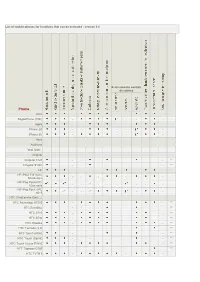

List of Mobile Phones for Functions That Can Be Activated - Version 5.4

List of mobile phones for functions that can be activated - version 5.4 Scaricamento contatti da rubrica Phone Amoi SkypePhone (TRE) - - - - Apple iPhone 2G - - - - - iPhone 3G - - - - Asus Audiovox Vedi Qtek... Cingular Cingular 8125 - - - ** Cingular SYNC - - - ** HP HP iPAQ 514 Voice - - - - - Messenger HP iPaq Pocket PC - - -* - - - - - - 63xx serie HP iPaq Pocket PC -* - - -* - - 6515 HTC (Vedi anche Qtek....) HTC Advantage X7500 - - ** HTC Excalibur - - - ** HTC S710 - - ** HTC S730 - - ** HTC Shadow - - ** HTC Tornado (2.0) ** HTC Touch (Alltel) - - - ** HTC Touch (Sprint) - - - - ** HTC Touch Cruise P3650 - - ** HTC Typhoon C500 ** HTC TyTN II - - - HTC Wizard ** Qteck/HTC P3300 - - - - - - - Qteck/HTC Touch Diamond - - - i-Mate Vedi Qtek LG LG CU500 - - ** LG KE850 - - - - - - - - LG KE850 Prada - - - ** LG KG800 (Chocolate) - - - - - - - - ** LG KS20 - - ** LG KU990 - - - ** LG KU800 - - - - - - - - - ** LG Shine (CU720) N N N ** LG Trax (CU575) N N N N N N ** LG U8550 - - - - -* LG U880 - - - - - - - - LG U900 - - - - - - - - Motorola Motorola A830/ - - - - A835 Motorola A1000 - - - - -* - Motorola A1200 Ming N ** Motorola E1000 - Motorola E398 - - - Motorola i615 N ** Motorola i880 N ** Motorola KRZR K1 - Motorola MPX220 - - - - - - Motorola RAZR2V9/ KRZR K3/ RAZR V3xx/ RAZR - MaxxV6 Motorola RAZR V3i/V3r ** Motorola RAZR V3t ** Motorola RAZR V6 Maxx ** Motorola RIZR Z3 - Motorola ROKR E6 N N ** Motorola Sidekick Slide N N N N ** Motorola SLVR L6 - Motorola SLVR L7 - Motorola U9 N N ** Motorola RAZR V3 - - Motorola V8 - - Motorola -

Kinh Nghiem Uprom Dong May HTC V.07.10.07

Kinh nghi ệm uprom dòng máy HTC: b ắt ñầu t ừ ñâu? Mở ñầu: Sau khi mua máy Pocket PC phone, ñiều ñầu tiên là tôi lao vào các di ễn ñàn ñể tìm thông tin, m ột m ặt là tìm hi ểu v ề ph ần m ềm dùng trên PPC m ặc khác là tìm hi ểu v ề chuy ện UPROM nó ra làm sao?. Tuy nhiên, sau khi ñọc m ột lo ạt các thông tin, tôi b ắt ñầu th ấy có 2 ñiều ñáng s ợ. 1. Sợ là vì b ỏ ti ền ra mua máy khoảng 10-12 tri ệu ñồng nh ưng sau khi ham vui UPROM xong thì máy thành “c ục g ạch” ch ặn gi ấy ñen ngòm mà không bi ết ph ải làm sao? Vậy mà sau khi ki ếm ñủ thông tin thì tôi v ẫn còn s ợ. 2. Cái s ợ th ứ 2: là ñã có ñủ thông tin, nh ưng ña s ố bài vi ết ch ỉ mô t ả b ằng ch ữ là chính mà không có hình ảnh. Cái này nó gi ống nh ư là h ọc sinh ti ểu h ọc nghe th ầy giáo mô t ả “con trâu” nh ưng ch ưa bao gi ờ th ấy con trâu ra làm sao?. ðiều này th ật s ự ñáng s ợ. Tuy nhiên sau m ột h ồi tìm ki ếm, thì c ũng có m ột s ố di ễn ñàn h ọ mô t ả vi ệc upROM b ằng hình ảnh, ñiều này th ật s ự h ữu ích cho nh ững ng ười m ới b ắt ñầu. -

How-To Install Any 2.X ROM in a CID-Locked G3 Or G4 Wizard

How-to install any 2.x ROM in a CID-Locked G3 or G4 Wizard. Disclaimer THE PROCEDURE I’M GOING TO EXPLAIN DEALS WITH ROM ‘COOKING’ AND THUS IT MAY CAUSE SEVERE DATA LOSS OR EVEN IRREMEDIABLY DAMAGE YOUR DEVICE! THE AUTHOR, NOR EVERY OTHER PERSON INVOLVED (E.G. THE ROM TOOLS DEVELOPERS), SHALL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY MALFUNCTIONS OR DAMAGES THIS PROCEDURE MAY CAUSE. USERS MUST AGREE TO THE TERMS OF THIS DISCLAIMER BEFORE THEY GO ON READING. Introduction This guide was written to answer all the e-mails and private messages I’ve received since I wrote on the Forum that I was successfully able to install an Italian ROM on a CID-Locked, English, G4 Wizard. Installing any 2.x ROM in a CID locked Wizard (either G3 or G4) is actually possible and I’ll show you how to do. I’d like to make clear that either the procedure you’re going to read or the tools we’ll use HAVE NOT BEEN INVENTED/CREATED/PROGRAMMED BY ME!!! So, if you’ll succeed in installing a new ROM on your device, it is not me you’ll have to thank. Credits for this How-To must go to the smart and brilliant developers that populate our Forum. Thank you all guys!!! Glossary (in order of importance) Forum: the greatest forum ever made: http://forum.xda-developers.com/front_page.php HTC Wizard: Wizard (or Prodigy) is the codename of a Windows Mobile Phone made by HTC and sold with many different names all around the world: XDA Mini S; MDA Vario; Qtek 9100; I-Mate K-Jam; Dopod 838; Cingular 8125; T-Mobile MDA; VPA Compact II; SPV M3000. -

Supported Devices

Scotia Mobile Banking Supported Mobile Devices (Applies for Mobile Banking services offered in the Caribbean) Scotia Mobile supports a wide variety of mobile devices, in this list you can find some of the most common Mobile Devices Manufacturers; there may be some other Devices supported that are not included in the list. HTC Apple LG Nokia Samsung Google Motorola Blackberry Sony Ericsson MANUFACTURER MODEL Apple All Mobile Devices Google All Mobile Devices DoCoMo Pro Series HT-02A HTC MP6950SP htc smart HTC HTC 2125 HTC MTeoR HTC Snap HTC 3100 (Star Trek) HTC Nexus One HTC Snap/Sprint S511 HTC 6175 HTC Nike HTC Sprint MP6900SP HTC 6277 HTC O2 XDA2Mini HTC ST20 HTC 6850 HTC P3300 HTC T8290 HTC 6850 Touch Pro HTC P3301/Artemis HTC Tattoo HTC 8500 HTC P3350 HTC Tilt 2 HTC 8900/Pilgrim/Tilt HTC P3400i (Gene) HTC Tornado HTC 8900b HTC P3450 HTC Touch HTC 9090 HTC P3451 (Elfin) HTC Touch 3G T3232 HTC ADR6300 HTC P3490/Diamond HTC Touch Cruise HTC Android Dev Phone 1 HTC P3600 Trinity HTC Touch Cruise (T4242) HTC Apache HTC P3651 HTC Touch Diamond HTC Artist HTC P3700/Touch Diamond HTC Touch Diamond2 (T5353) HTC P3702/Touch HTC Atlas Diamond/Victor HTC Touch HD HTC Breeze HTC P4000 HTC Touch HD T8285 HTC Touch Pro (T7272/TyTn HTC Cingular 8125 HTC P4350 III) HTC Cleo HTC P4351 HTC Touch Pro/T7373 HTC Corporation Touch2 HTC P4600 HTC Touch Viva HTC Dash HTC P5310BM HTC Touch_Diamond HTC Dash 3G (Maple) HTC P5500 HTC TouchDual HTC Desire HTC P5530 (Neon) HTC TyTN HTC Dream HTC P5800 (Libra) HTC TyTN II HTC Elf HTC P6500 HTC v1510 HTC Elfin HTC -

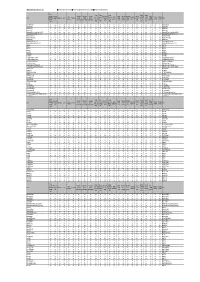

Bluetooth Firmware Version 1.43 Yes = Feature Is

Bluetooth firmware Version 1.43 yes = Feature is supported and confirmed. n o = Feature is not supported by the Kenwood Bluetooth Module. n /a = Feature is not supported by the Phone. Phone Pick-up Refuse Hang-up Enable to Enable to connection Pick-up and Phonebook SIM contacts Call register Switch call in Display Phonebook Phonebook Enable to Enable to Reject second call second call active call in Display Phonebook use AVRCP read SMS Enable to Notify about Phone to KENWOOD hang-up a Dial number Redial Private mode automatic automatic automatic three way network transfer - transfer - use A2DP read SMS Phone incoming call in three way in three way three way battery level transfer - all Target from SIM send SMS new SMS Bluetooth call synchronisation synchronisation synchronisation calling level one by one selection profile from phone calling calling calling profile card Model BenQ-Siemens CL71 no yes yes yes no no n/a n/a n/a no n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a yes yes yes n/a n/a n/a n/a no n/a BenQ-Siemens CL71 Blackberry 7105t yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes n/a n/a n/a n/a yes yes n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a no n/a Blackberry 7105t Blackberry 7130g yes yes yes yes yes yes yes n/a n/a yes yes yes yes yes yes n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a no n/a Blackberry 7130g Blackberry 7290 yes yes yes yes yes yes no n/a n/a yes yes yes yes yes yes n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a no n/a Blackberry 7290 Blackberry 8100 Pearl - Tmobile /Rom Ver.4.2.0.42 yes yes yes yes yes no yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes n/a n/a n/a n/a no n/a Blackberry 8100 Pearl