The Right's Reasons: Constitutional Conflict and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control Jonathan Will Mississippi College School of Law, [email protected]

Mississippi College School of Law MC Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Publications 2018 Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control Jonathan Will Mississippi College School of Law, [email protected] I. Glenn Cohen Harvard Law School, [email protected] Eli Y. Adashi Brown University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.mc.edu/faculty-journals Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons Recommended Citation 93 Ind. L. J. 499 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at MC Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of MC Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control* JONATHAN F. WILL, JD, MA, 1. GLENN COHEN, JD & ELI Y. ADASHI, MD, MSt Just three days prior to the inaugurationof DonaldJ. Trump as President of the United States, Representative Jody B. Hice (R-GA) introducedthe Sanctity of Human Life Act (H R. 586), which, if enacted, would provide that the rights associatedwith legal personhood begin at fertilization. Then, in October 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services releasedits draft strategicplan, which identifies a core policy of protectingAmericans at every stage of life, beginning at conception. While often touted as a means to outlaw abortion, protecting the "lives" of single-celled zygotes may also have implicationsfor the practice of reproductive medicine and research Indeedt such personhoodefforts stand apart anddistinct from more incre- mental attempts to restrictabortion that target the abortionprocedure and those who would perform it. -

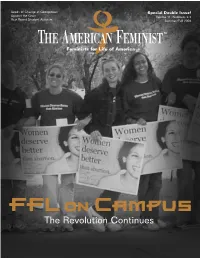

Summer-Fall 2004: FFL on Campus – the Revolution Continues

Seeds of Change at Georgetown Special Double Issue! Against the Grain Volume 11, Numbers 2-3 Year-Round Student Activism Summer/Fall 2004 Feminists for Life of America FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues ® “When a man steals to satisfy hunger, we may safely conclude that there is something wrong in society so when a woman destroys the life of her unborn child, it is an evidence that either by education or circumstances she has been greatly wronged.” Mattie Brinkerhoff, The Revolution, September 2, 1869 SUMMER - FALL 2004 CONTENTS ....... FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues 3 Revolution on Campus 28 The Feminist Case Against Abortion 2004 The history of FFL’s College Outreach Program Serrin Foster’s landmark speech updated 12 Seeds of Change at Georgetown 35 The Other Side How a fresh approach became an annual campus- Abortion advocates struggle to regain lost ground changing event 16 Year-Round Student Activism In Every Issue: A simple plan to transform your campus 38 Herstory 27 Voices of Women Who Mourn 20 Against the Grain 39 We Remember A day in the life of Serrin Foster The quarterly magazine of Feminists for Life of America Editor Cat Clark Editorial Board Nicole Callahan, Laura Ciampa, Elise Ehrhard, Valerie Meehan Schmalz, Maureen O’Connor, Molly Pannell Copy Editors Donna R. Foster, Linda Frommer, Melissa Hunter-Kilmer, Coleen MacKay Production Coordinator Cat Clark Creative Director Lisa Toscani Design/Layout Sally A. Winn Feminists for Life of America, 733 15th Street, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20005; 202-737-3352; www.feministsforlife.org. President Serrin M. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

Does the Fourteenth Amendment Prohibit Abortion?

PROTECTING PRENATAL PERSONS: DOES THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT PROHIBIT ABORTION? What should the legal status of human beings in utero be under an originalist interpretation of the Constitution? Other legal thinkers have explored whether a national “right to abortion” can be justified on originalist grounds.1 Assuming that it cannot, and that Roe v. Wade2 and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylva- nia v. Casey3 were wrongly decided, only two other options are available. Should preborn human beings be considered legal “persons” within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, or do states retain authority to make abortion policy? INTRODUCTION During initial arguments for Roe v. Wade, the state of Texas ar- gued that “the fetus is a ‘person’ within the language and mean- ing of the Fourteenth Amendment.”4 The Supreme Court rejected that conclusion. Nevertheless, it conceded that if prenatal “per- sonhood is established,” the case for a constitutional right to abor- tion “collapses, for the fetus’ right to life would then be guaran- teed specifically by the [Fourteenth] Amendment.”5 Justice Harry Blackmun, writing for the majority, observed that Texas could cite “no case . that holds that a fetus is a person within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.”6 1. See Antonin Scalia, God’s Justice and Ours, 156 L. & JUST. - CHRISTIAN L. REV. 3, 4 (2006) (asserting that it cannot); Jack M. Balkin, Abortion and Original Meaning, 24 CONST. COMMENT. 291 (2007) (arguing that it can). 2. 410 U.S. 113 (1973). 3. 505 U.S. 833 (1992). 4. Roe, 410 U.S. at 156. Strangely, the state of Texas later balked from the impli- cations of this position by suggesting that abortion can “be best decided by a [state] legislature.” John D. -

The Partisan Trajectory of the American Pro-Life Movement: How a Liberal Catholic Campaign Became a Conservative Evangelical Cause

Religions 2015, 6, 451–475; doi:10.3390/rel6020451 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article The Partisan Trajectory of the American Pro-Life Movement: How a Liberal Catholic Campaign Became a Conservative Evangelical Cause Daniel K. Williams Department of History, University of West Georgia, 1601 Maple St., Carrollton, GA 30118, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-678-839-6034 Academic Editor: Darren Dochuk Received: 25 February 2015 / Accepted: 3 April 2015 / Published: 16 April 2015 Abstract: This article employs a historical analysis of the religious composition of the pro-life movement to explain why the partisan identity of the movement shifted from the left to the right between the late 1960s and the 1980s. Many of the Catholics who formed the first anti-abortion organizations in the late 1960s were liberal Democrats who viewed their campaign to save the unborn as a rights-based movement that was fully in keeping with the principles of New Deal and Great Society liberalism, but when evangelical Protestants joined the movement in the late 1970s, they reframed the pro-life cause as a politically conservative campaign linked not to the ideology of human rights but to the politics of moral order and “family values.” This article explains why the Catholic effort to build a pro-life coalition of liberal Democrats failed after Roe v. Wade, why evangelicals became interested in the antiabortion movement, and why the evangelicals succeeded in their effort to rebrand the pro-life campaign as a conservative cause. Keywords: Pro-life; abortion; Catholic; evangelical; conservatism 1. -

Interactions Between the Pro-Choice and Pro-Life Social Movements Outside the Abortion Clinic Sophie Deixel Vassar College

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2018 Whose body, whose choice: interactions between the pro-choice and pro-life social movements outside the abortion clinic Sophie Deixel Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Deixel, Sophie, "Whose body, whose choice: interactions between the pro-choice and pro-life social movements outside the abortion clinic" (2018). Senior Capstone Projects. 786. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/786 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vassar College Whose Body, Whose Choice: Interactions Between the Pro-Choice and Pro-Life Social Movements Outside the Abortion Clinic A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Bachelor of Arts in Sociology By Sophie Deixel Thesis Advisors: Professor Bill Hoynes Professor Erendira Rueda May 2018 Deixel Whose Body Whose Choice: Interactions Between the Pro-Choice and Pro-Life Social Movements Outside the Abortion Clinic This project explores abortion discourse in the United States, looking specifically at the site of the abortion clinic as a space of interaction between the pro-choice and pro-life social movements. In order to access this space, I completed four months of participant observation in the fall of 2017 as a clinic escort at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Poughkeepsie, New York. I thus was able to witness (and participate in) firsthand the interactions between the clinic escorts and the anti-abortion protestors who picketed outside of the clinic each week. -

Abortion: Judicial and Legislative Control

ABORTION: JU3ICIAL AND LEGISLATIVE CONTROL ISSUE BRIEF NUMEER IB74019 AUTHOR: Lewis, Karen J. American Law Division Rosenberg, Morton American Law Division Porter, Allison I. American Law Division THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE MAJOR ISSUES SYSTEM DATE ORIGINATED DATE UPDATED FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CALL 287-5700 1013 CRS- 1 ISSUE DEFINITION In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Constitution protects a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy, Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, and that a State may not unduly burden the exercise of that fundamental right by regulations that prohibit or substantially limit access to the means of effectuating that decision, Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179. But rather than settling the issue, the Court's rwlings have kindled heated debate and precipitated a variety of governmental actions at the national, State and local levels designed either to nullify the rulings or hinder their effectuation. These governmental regalations have, in turn, spawned further litigation in which resulting judicial refinements in the law have been no more successful in dampening the controversy. Thus the 97th Congress promises to again be a forum for proposed legislation and constitutional amendments aimed at limiting or prohibiting the practice of abortion and 1981 will see Court dockets, including that of the Supreme Court, filled with an ample share of challenges to5State and local actions. BACKGROUND AND POLICY ANALYSIS The background section of this issue brief is organized under five categories, as follows: I. JUDICIAL HISTORY A. Development and Status of the Law Prior to 1973 B. -

Introducing Women's and Gender Studies: a Collection of Teaching

Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 1 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Collection of Teaching Resources Edited by Elizabeth M. Curtis Fall 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 2 Copyright National Women's Studies Association 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 3 Table of Contents Introduction……………………..………………………………………………………..6 Lessons for Pre-K-12 Students……………………………...…………………….9 “I am the Hero of My Life Story” Art Project Kesa Kivel………………………………………………………….……..10 Undergraduate Introductory Women’s and Gender Studies Courses…….…15 Lecture Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Jennifer Cognard-Black………………………………………………………….……..16 Introduction to Women’s Studies Maria Bevacqua……………………………………………………………………………23 Introduction to Women’s Studies Vivian May……………………………………………………………………………………34 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jeanette E. Riley……………………………………………………………………………...47 Perspectives on Women’s Studies Ann Burnett……………………………………………………………………………..55 Seminar Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Lynda McBride………………………..62 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jocelyn Stitt…………………………….75 Introduction to Women’s Studies Srimati Basu……………………………………………………………...…………………86 Introduction to Women’s Studies Susanne Beechey……………………………………...…………………………………..92 Introduction to Women’s Studies Risa C. Whitson……………………105 Women: Images and Ideas Angela J. LaGrotteria…………………………………………………………………………118 The Dynamics of Race, Sex, and Class Rama Lohani Chase…………………………………………………………………………128 -

The Effects of the Global Gag Rule on Democratic Participation and Political Advocacy in Peru, 31 Brook

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brooklyn Law School: BrooklynWorks Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 31 | Issue 3 Article 8 2006 The olitP ics of Gagging: The ffecE ts of the Global Gag Rule on Democratic Participation and Political Advocacy in Peru Rachael E. Seevers Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Rachael E. Seevers, The Politics of Gagging: The Effects of the Global Gag Rule on Democratic Participation and Political Advocacy in Peru, 31 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol31/iss3/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. THE POLITICS OF GAGGING: THE EFFECTS OF THE GLOBAL GAG RULE ON DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION AND POLITICAL ADVOCACY IN PERU I. INTRODUCTION he United States is one of the world’s largest donor countries to Tglobal family planning activities.1 The majority of its international grants to foreign providers come under the auspices of United States Aid for International Development (USAID) grants, making the United States an important player in global family planning.2 The 2001 reinstatement of the historically controversial “Mexico City Policy” attaches wide ranging aid conditionalities to the receipt of USAID funding, and effec- tively enables the United States to dictate the domestic and international family planning policies of recipient countries.3 Many of these funding restrictions relate to the provision of abortion services and counseling.4 In addition, some of the policy’s provisions are aimed at curtailing politi- cal advocacy for liberalized abortion regulation by foreign recipient non- governmental organizations (NGOs).5 The restrictions of the U.S. -

![The Silent Scream (1984), by Bernard Nathanson, Crusade for Life, and American Portrait Films [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3175/the-silent-scream-1984-by-bernard-nathanson-crusade-for-life-and-american-portrait-films-1-1573175.webp)

The Silent Scream (1984), by Bernard Nathanson, Crusade for Life, and American Portrait Films [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) The Silent Scream (1984), by Bernard Nathanson, Crusade for Life, and American Portrait Films [1] By: Zhang, Mark Keywords: Abortion [2] ultrasound [3] Bernard Nathanson [4] The Silent Scream is an anti-abortion [5] film released in 1984 by American Portrait Films, then based in Brunswick, Ohio. The film was created and narrated by Bernard Nathanson, an obstetrician and gynecologist from New York, and it was produced by Crusade for Life, an evangelical anti-abortion [5] organization [6]. In the video, Nathanson narrates ultrasound [7] footage of an abortion [5] of a twelve-week-old fetus [8], claiming that the fetus [8] opened its mouth in what Nathanson calls a silent scream during the procedure. As a result of Nathanson's anti-abortion [5] stance in the film, The Silent Scream contributed to the abortion [5] debate in the 1980s. From 1970 to 1972 Nathanson had directed in New York City, New York the Center for Reproductive and Sexual Health, which he called the largest abortion [5] facility in the western world at that time, and he claimed to help found the National Abortion Rights Action League in New York City. Though he had previously performed abortions, by 1982 Nathanson opposed the procedure, owing his changed stance to the technology of ultrasound [7], which allowed observation of fetuses during abortions. He created the film as a statement against abortion [5], stating that any form of violence should be opposed, including those against a fetus [8]. The Silent Scream begins in Nathanson's office, where he first informs the viewer that he is an obstetrician and a gynecologist and that he had previously performed thousands of abortions. -

Abortion at Or Over 20 Weeks' Gestation

Abortion At or Over 20 Weeks’ Gestation: Frequently Asked Questions Matthew B. Barry, Coordinator Section Research Manager April 30, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45161 Abortion At or Over 20 Weeks’ Gestation: Frequently Asked Questions Summary Legislation at the federal and state levels seeking to limit or ban abortions in midpregnancy has focused attention on the procedure and the relatively small number of women who choose to undergo such an abortion. According to the Guttmacher Institute, about 926,200 abortions were performed in 2014; 1.3% of abortions were performed at or over 21 weeks’ gestation in 2013. A 2018 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine study found that most women who have abortions are unmarried (86%), are poor or low-income (75%), are under age 30 (72%), and are women of color (61%). Stages of Pregnancy and Abortion Procedures A typical, full-term pregnancy spans 40 weeks, separated into trimesters: first trimester (week 1 through week 13), second trimester (week 14 through week 27), and third trimester (week 28 through birth). Abortion in the second trimester can be performed either by using a surgical procedure or by using drugs to induce labor. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2014 a surgical method was used for 98.8% of U.S. abortions at 14-15 weeks’ gestation, 98.4% at 16-17 weeks, 96.6% at 18-20 weeks, and 90.2% at 21 weeks or later. Proposed Legislation Related to Abortion Legislation in the 115th Congress, the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act (H.R. -

Early Abortion Exceptionalism

University of Pittsburgh School of Law Scholarship@PITT LAW Articles Faculty Publications 2021 Early Abortion Exceptionalism Greer Donley University of Pittsburgh School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, Fourteenth Amendment Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Recommended Citation Greer Donley, Early Abortion Exceptionalism, 107 Cornell Law Review, forthcoming (2021). Available at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles/404 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship@PITT LAW. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@PITT LAW. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Draft as of May 23, 2021 Early Abortion Exceptionalism Greer Donley Forthcoming in Vol. 107 of the Cornell Law Review Abstract: Restrictive state abortion laws garner a large amount of attention in the national conversation and legal scholarship, but less known is a federal abortion policy that significantly curtails access to early abortion in all fifty states. The policy limits the distribution of mifepristone, the only drug approved to terminate a pregnancy so long as it is within the first ten weeks. Unlike most drugs, which can be prescribed by licensed healthcare providers and picked up at most pharmacies, the Food and Drug Administration only allows certified providers to prescribe mifepristone, and only allows those providers to distribute the drug to patients directly, in person, not through pharmacies.