Baking for Biodiversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Household Auction- 840 N

09/30/21 06:16:31 Household Auction- 840 N. 10th Street Sacramento - February 9 Auction Opens: Fri, Feb 5 2:07pm PT Auction Closes: Tue, Feb 9 6:30pm PT Lot Title Lot Title B0131 Lodge Dutch Oven B0190 Nespresso Vertuo Next & Aeroccino3 B0132 Tire Chains B0191 Shark IQ Robot B0133 Veggie 5-Blade Spiralizer B0192 Brew Cordless Glass Electric Kettle B0134 Taylor Digital Scale B0193 Wireless Pet Containment System B0135 Dutch Oven B0194 Glass Jug B0136 Dutch Oven B0195 Glass Jug B0137 Dutch Oven B0196 Electric Rotisserie Air Fryer Oven B0138 3-Tier Rolling Cart B0197 Shark Rocket B0139 Nespresso Vertuo NEXT B0198 Shark Wandvac B0140 Reverse Osmosis Water Storage Tank B0199 Cuisinart Ice Cream Maker B0141 Prepworks Baker's Storage Set B0200 Ovitus Foot massager B0142 Prepworks Baker's Storage Set B0201 Foot massager B0143 Sodastream Fizz one Touch B0203 Foot Spa Massager with Heat Bubbles and B0144 PowerXL Grill Air Fryer Combo Vibration B0145 Cuisinart Ice Cream Maker B0204 Kicker Comp B0146 Cuisinart Ice Cream Maker B0205 Rubbermaid Food Container B0147 Dutch Oven Minor Damage B0206 Tripod Floor Lamp B0148 Sunbeam Microwave Oven B0207 Convection Electric Oven B0149 Gourmia Digital Air Fryer B0208 Saddle Counter Stoo B0150 Sharper Image Tranquility Spa Sound Soother B0209 newair Oil Filled Personal Heater B0151 Homedics Total Comfort Plus Ultrasonic B0210 Ninja Air Fry Oven Humidifier B0211 Air Fryer B0152 Gourmia Digital Air Fryer B0212 Safe B0153 Cookware B0213 Nouveau Glass Cake Stand B0154 Hamilton Beach Coffee Maker B0214 Hamilton Beach -

New Innovations from Calphalon Help Home Cooks to Get Better Results in the Kitchen

New Innovations from Calphalon Help Home Cooks to Get Better Results in the Kitchen October 25, 2019 Calphalon Introduces New Appliances, Cookware, Bakeware, and Cutlery BOCA RATON, Fla., Oct. 25, 2019 /PRNewswire/ -- Calphalon, a leader in premium cookware, bakeware, cutlery and small kitchen appliances, is introducing a new assortment of products designed to achieve better culinary results in the kitchen. These new high performance products allow at-home chefs to create exceptional recipes with precision and satisfaction. The new assortment features the durable construction and precise craftsmanship consumers expect from Calphalon, along with elevated aesthetics that home chefs will be excited to show off on countertops. The new Calphalon offerings range from $59.99 - $299.99 and are available nationwide both in stores and online at a variety of retailers. Details of each new product can be found below: The Calphalon ClassicTM Nonstick Cookware with No-Boil-Over Insert Set ($299.99) contains innovative BPA-free silicone no-boil-over inserts that put a stop to messy spills when making pasta, rice, potatoes, and beans—giving you the freedom to focus on other tasks while cooking. The BPA-free silicone inserts recirculate boiling water back into the pot to prevent messy boil-over spills. The 14-piece PFOA-free set includes 8-inch fry pan, 10-inch fry pan, 12-inch fry pan with cover, 1.5-quart sauce pot with cover, 2.5-quart sauce pot with cover and no-boil-over insert, 3-quart sauté pan with cover, 6-quart stock pot with cover and no-boil-over insert. -

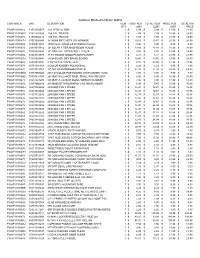

Container Upc Description Item Qty Cost Per Unit Total

Container Manifest for Order: 369054 CONTAINER UPC DESCRIPTION ITEM COST PER TOTAL ITEM PRICE PER TOTAL ITM QTY UNIT COST UNIT PRICE FWAP113W682 81972502047 1:64 HITCH & TOW 1 $ 5.99 $ 5.99 $ 11.99 $ 11.99 FWAP113W5DV 81972502089 1:64 S.D. TRUCKS 1 $ 7.99 $ 7.99 $ 14.99 $ 14.99 FWAP113W67V 81972502212 1:64 S.D. TRUCKS 1 $ 7.99 $ 7.99 $ 14.99 $ 14.99 FWAP113W67H 87519500340 10' 3000# RATCHETX 2PK ORANGE 1 $ 10.15 $ 10.15 $ 20.99 $ 20.99 FWAP113W685 07934611457 1000 PIECE CHARLES WYSOCKI PUZZLE 1 $ 5.40 $ 5.40 $ 9.99 $ 9.99 FWAP113W672 09333513342 12" SOLAR 3 TIER MUSHROOM HOUSE 1 $ 13.88 $ 13.88 $ 34.99 $ 34.99 FWAP113W67J 75745608650 16" ANALOG LATTICE WALL CLOCK 1 $ 5.70 $ 5.70 $ 14.99 $ 14.99 FWAP113W685 68049153579 17.75" ROUND WOOD PLANK PLANTER 1 $ 6.31 $ 6.31 $ 21.99 $ 21.99 FWAP113W67H 72901609484 18X24 BLACK DRY ERASE BOARD 1 $ 10.45 $ 10.45 $ 23.99 $ 23.99 FWAP113W66V 04892919987 2 3/4" WHITE 500PK TEES 4 $ 6.35 $ 25.40 $ 17.99 $ 71.96 FWAP113W67Y 03314904169 2 COLOR KNOBBY ROUND BALL 1 $ 2.28 $ 2.28 $ 4.99 $ 4.99 FWAP113W672 09333513763 20" SOLAR MUSHROOM STATUE 1 $ 32.38 $ 32.38 $ 69.99 $ 69.99 FWAP113W66W 03857668428 2018 AYCOLOR POP POCKET WM PLANNER W/BU 1 $ 3.80 $ 3.80 $ 7.99 $ 7.99 FWAP113W68D 03857634709 2019EAT-A-GLANCE ARIEL SMALL W/M SENZO P 1 $ 8.50 $ 8.50 $ 16.99 $ 16.99 FWAP113W677 03857641209 2019EAT-A-GLANCE SMALL WEEKLY PLANNER 1 $ 7.00 $ 7.00 $ 13.99 $ 13.99 FWAP113W676 03857660389 2019EMEAD TYPOGRAPHY LRG WM PLANNER 1 $ 5.45 $ 5.45 $ 10.99 $ 10.99 FWAP113W66U 04601342292 20IN BOX FAN 3 SPEED 1 $ 12.47 $ 12.47 -

Download Mod

download mod dst Don’t Starve: Pocket Edition MOD APK 1.19.2 (Unlocked All Characters) If you want to try all characters of Don’t Starve: Pocket Edition, please download the MOD version via the links below the article. Introduce about Don’t Starve: Pocket Edition. Don’t Starve: Pocket Edition is a survival simulator game set in a mysterious wasteland. Now, fans of mobile games will be able to sink into a world filled with gloom – where you must use the best qualities to protect yourseft. Join Don’t Starve: Pocket Edition and prove to evil demons that you are ready for all difficulties, hardships and fears. Monsters lurking in the dark, hungry and cold can make you fall down at any moment. The storyline. Wilson is a young scientist. Besides the scientific works, he regularly participates in expeditions in new lands. One time, he accidentally got lost in the wild. The landscape here is very murky, and there seems to be no way out. Faced with problems such as extreme weather, food shortages and near-dangers, what will Wilson do to survive until he finds his way home? Challenge your ability to survive in the wild. Don’t Starve: Pocket Edition takes you to a wild world, where conditions are harsh and dangers that can leave you down at any moment. And as the title says, your goal is to help Wilson keep his mental health in a stable state. So, how to do that? You move around in the map, looking for sources of food and water. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

PEPPER MILLS a Comparitive Analysis of DESIGN Written by NIKKI PINNEY for DI91: Design Studies FORM + FUNCTION

PEPPER MILLS a comparitive analysis of DESIGN written by NIKKI PINNEY for DI91: design studies FORM + FUNCTION September 17, 2012 INTRODUCTION AESTHETIC ANALYSIS In this analysis, I compare and contrast the form and function two pepper mills, one a burr-style crank grinder (Figure 1), the other a spring-loaded push grinder (Firgure 2). I hand-cranked spring-loaded contextualize their structural and aesthetic distinction by examining the history of pepper mill use and display in the home. Finally,drawing from my observations and judgments of Lightweight; the two objects’ features, I offer suggestions for an iteration of their design. WEIGHT Solid; not heavy but not VS easily knocked over by lightweight a brush of the hand Light tan and beige Clear with COLOR striations; silver VS semi-transparent dark orange; silver Curvy hourglass figure Cylindrical with smooth SHAPE with tapered middle; VS but not rounded edges offset crank handle Approx. 5.5 inches by 3 Approx. 4 inches by 1 SIZE inches; crank reaches VS inch add’l inch MATERIALS Wood and metal VS Plastic and metal Small “Mr. Dudley” logo TEXT on the gear, not None Fig. 1: burr-style crank grinder Fig. 2: spring-loaded push grinder VS immediately visible Smooth, polished; slight Mostly smooth encase- TEXTURE natural speckling of VS ment; spring presents a BACKGROUND wood grain at touch tactile contrast The history of pepper mills and pepper shakers, were and Knoppy has been handed down becoming a mainstay on Hoffman, who boast a The hand-cranked pepper mill is The cylindrical, linear shape of the like so many recipes; American kitchen tables collection of 600 grinders made from rich materials which, spring-loaded pepper mill is sug- approximations are de (Western Illinois Museum, (Suqi, 2012), the premise of along with its size, contribute to a gestive of modern design, as are rigeur. -

Collective Trademarks and Artisanship in Michoacán, Mexico

INTERNATIONAL PHD IN LAW AND SOCIETY “RENATO TREVES” Regulating Signifiers: Collective Trademarks and Artisanship in Michoacán, Mexico Lucero Ibarra Rojas Supervisors: Sol Picciotto Luigi Cominelli 1 INDEX Acknowledgements 3 Glossary 6 Introduction 8 1. Culture in México's colonial history and Michoacán's artisanal sector 17 1.1 México: historical space in construction 20 1.2 Pinpointing Michoacán 30 2. The turn toward intellectual property for Michoacán 42 2.1 Methodology 44 2.2 Indigenous cultural expressions and the limitations of Intellectual 48 Property 2.3 Problems and inspirations: where it all began 52 2.4 Intellectual property in the technocratic agenda: the rightist project 63 2.5 The artisanship in Michoacán’s law 69 2.6 Intellectual property in the pluricultural agenda: the leftist project 81 3. The implementation of the Collective Trademarks public policy 90 3.1 Negotiating Collective Trademarks 92 3.2 The integration of a pilot project 100 3.3 CASART trade marketing Michoacán 108 3.4 Heterogeneity within the state 115 REGULATING SIGNIFIERS: COLLECTIVE TRADEMARKS AND ARTISANSHIP IN MICHOACÁN, MEXICO | Lucero Ibarra Rojas 2 4. Collective Trademarks through the shifts in Michoacán’s public 118 administration 4.1 The changes in the CASART administration and its effects for 121 Collective Trademarks 4.2 The SEDECO’s involvement with Collective Trademarks 129 4.3 The Collective Trademarks in Michoacán’s PRI administration 137 4.4 The heterogeneity of the state and the political field 140 5. Living the collective trademarks: The meaning of collective trademarks 143 for Michoacán’s communities 5.1 Methodological approach 145 5.2 Where did the trademarks go? 152 5.3 Persisting with Collective Trademarks 162 5.4 Intellectual property and epistemic hegemonies 171 5.5 Counter Hegemonic possibilities 180 Conclusions 188 References 197 REGULATING SIGNIFIERS: COLLECTIVE TRADEMARKS AND ARTISANSHIP IN MICHOACÁN, MEXICO | Lucero Ibarra Rojas 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Truly there is no idea that comes from nothing, or creation endeavour that involves a single mind. -

Global Journal of Engineering Science And

[Ngabea, 2(8): August 2015] ISSN 2348 – 8034 Impact Factor- 3.155 GLOBAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCE AND RESEARCHES DESIGN, FABRICATION AND PERFORMANCE EVALUATION OF A MAGNETIC SIEVE GRINDING MACHINE S.A Ngabea*1, W.I Okonkwo*1 and J.T Liberty2 *1Department of Bioresource Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State 2Department of Crop Production and Protection, Federal University Dutsin-ma, Katsina State ABSTRACT The use of grinding machine is one of the simplest methods of processing agricultural raw materials alternative to the traditional methods of grain/tuber processing using stone, mortar and pestle. However, machines constructed using metal plates results in tearing and wearing away of the materials of construction. The effect of this is the contamination of the processed foodstuff. This is known to have negative health implications when accumulated and consumed in large quantities. In this study, a magnetic sieve grinding machine was designed, constructed and the performance evaluation undertaken in order to remove the toxic metal filing contaminants that cause the health hazard in food when consumed. The machine consists of a 0.04m3 capacity hopper, a machine housing, a blower with 13.35m/s air speed, a cyclone, set of hammers that effect the size reduction of the materials been fed, 12cm width rotor pulley, a shaft of 50cm in length and a magnetic sieve that separate metal filings from the grounded food stuff. The machine is powered by a 5.96 kW diesel engine. Performance evaluation showed that 10.5g of the machine parts were worn out after 10hours of grinding. The throughput capacity and the efficiency of the machine are 600kg/hr and 87.5% respectively. -

AE 304 Physical Properties of Agrucultural Products (3 Units)

LANDMARK UNIVERSITY, OMU-ARAN DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL AND BIOSYSTEMS ENGINEERING Code: ABE 512 Title: Processing & Storage of Agricultural Products Credit: 3 Properties and characteristics of agricultural materials in relation to their Processing and handling methods. Physical, mechanical, rheological, thermal, electrical and chemical properties. Introduction to agricultural product processing, Ambient temperature processing Materials cleaning, sorting and grading techniques. Size reduction and mixing, Processing by application of heat. Handling methods. Storage requirement of agricultural products. Properties and Characteristics of Agricultural Materials Physical Properties of Agricultural Products: Shape size, volume, surface area, density, porosity, colour and appearance are some of the physical characteristics which are important in many problems associated with design of specific machine or analysis of the behavior of the product in handling of the material. When studying physical properties of Agricultural products by considering either bulk or individual units of the material it is important to have an accurate estimate of these properties which may be considered as engineering parameters for that product. Shape and size: In a physical object shape and size are inseparable and both are generally necessary if the object is to be satisfactorily described. In defining the size the three principal dimensions namely the length, width and thickness (major, minor intermediate diameter) are measured to a given accuracy. a b c The principal dimensions are measured using different methods such as photographic enlarger, millimeter scale, a shadow graph, tracing of projected area or by the use of micrometer. The major minor and intermediate diameter of an object can be measured by projection of each sample using photographic enlarger. -

Business Relations, Identities, and Political Resources of the Italian

European Review of History Revue européenne d’histoire Volume 23 Number 3 June 2016 CONTENTS—SOMMAIRE DOSSIER: Business Relations, Identities, and Political Resources of the Italian Merchants in the Early-Modern Spanish Monarchy / Relations commerciales, identités et ressources politiques des marchands italiens dans la Monarchie espagnole à l’époque moderne GUEST EDITORS: Catia Brilli and Manuel Herrero Sánchez The business relations, identities and political resources of Italian merchants in the early-modern Spanish monarchy: some introductory remarks Manuel Herrero Sánchez 335 Tuscan merchants in Andalusia: a historiographical debate Angela Orlandi 347 A Genoese merchant and banker in the Kingdom of Naples: Ottavio Serra and his business network in the Spanish polycentric system, c.1590–1620 Yasmina Rocío Ben Yessef Garfia 367 Looking through the mirrors: materiality and intimacy at Domenico Grillo’s mansion in Baroque Madrid Felipe Gaitán Ammann 400 Small but powerful: networking strategies and the trade business of Habsburg-Italian merchants in Cadiz in the second half of the eighteenth century Klemens Kaps 427 Coping with Iberian monopolies: Genoese trade networks and formal institutions in Spain and Portugal during the second half of the eighteenth century Catia Brilli 456 I. ARTICLES—ARTICLES Politics of place: political representation and the culture of electioneering in the Netherlands, c.1848–1980s Harm Kaal 486 A regionalisation or long-distance trade? Transformations and shifts in the role of Tana in the Black Sea trade in -

2009.10月月月hiphop,R&B 621 曲

2009.10 月月月月月月月月HIPHOP,R&B 621 曲曲曲、曲、、、1.6 日日日、日、、、4.63 GB 名名名名名名 アアアアアアアアアアアアアア アアアアアアアアアア BPM Outta Control (133 Bpm) Baby Bash Feat. Pitbull Funkymix 127 Sweet Dreams (128 Bpm) Beyonce Funkymix 127 Wasted (77 Bpm) Gucci Mane Feat. Oj Da Juiceman Funkymix 127 Whatcha Say (Part 1) (72 Bpm) Jason Derulo Funkymix 127 Whatcha Say (Part 2) (138 Bpm) Jason Derulo Funkymix 127 Run This Town (85 Bpm) Jay Z Feat. Rihanna And Kanye West Funkymix 127 Now Im That Bitch (Xxx) (123 Bpm) Livvi Franc Feat. Pitbull Funkymix 127 Now Im That Chick (123 Bpm) Livvi Franc Feat. Pitbull Funkymix 127 Trickn (138 Bpm) Mullage Funkymix 127 Number 1 (138 Bpm) R. Kelly Feat. Keri Hilson Funkymix 127 He Aint Wit Me Now (108 Bpm) Rich Girl Funkymix 127 Shake My (125 Bpm) Three 6 Mafia Feat. Kalenna Funkymix 127 Forever (79 Bpm) Drake Ft Kanye' West, Lil' Wayne & Eminem Funkymix 128 Drop it Low (88 Bpm) Ester Dean & Chris Brown Funkymix 128 Get Involved (122 Bpm) Ginuwine Ft Timbaland & Missy Elliott Funkymix 128 Replay (91 Bpm) I-Yaz Funkymix 128 Digital Girl (107 Bpm) Jamie Foxx Ft Drake & the-Dream Funkymix 128 Empire State of Mind (87 Bpm) Jay-Z Ft Alicia Keys Funkymix 128 Give it All U Got (125 Bpm) Lil' Jon Ft Kee Funkymix 128 LOL :) (78 Bpm) Trey Songz Ft Gucci Mane & Soulja Boy Funkymix 128 5 Star (77 Bpm) Yo Gotti Funkymix 128 Written On Her 125bpm Birdman Ft Jay Sean Future Heat Vol 9 Meet Me Halfway [PB Remix] 132bpm Black Eyed Peas Future Heat Vol 9 Unusual You 124bpm Britney Spears Future Heat Vol 9 Switch 120bpm Ciara Future Heat Vol 9 On To You 124bpm -

Pdf, 544.91 KB

00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Three gavel bangs.] 00:00:01 Jesse Host Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman podcast. I'm Bailiff Jesse Thorn. We're in chambers this week, clearing the docket! How are you, Judge Hodgman? 00:00:11 John Host I'm freezing! [Laughs.] It's—winter really happened! [Jesse laughs quietly.] Here in Brooklyn, New York. It's really happening now, finally. And of course as I record from my office, and rather than have a proper heating system, my office instead has a giant hairdryer stuck in the wall... [Both laugh.] A loud hot air machine that just blows hot air in your face until your lips turn to corn husks. [Jesse laughs.] Not good for podcast recording so I had to, you know, turn that off, and now I'm cold! But I can't complain. I mean, I—I'm doing it, but I shouldn't. 'Cause everything's great! How are you, Jesse? 00:00:50 Jesse Host I'm doing okay. I too could use a midwinter celebration. A little break. Something special to remind me that spring is just around the corner. Can you think of anything? 00:01:06 John Host Uh, let's... take the day off. [Both laugh.] 00:01:10 Jesse Host Welp! That's it for this week's Judge John Hodgman podcast! [Both laugh.] We're gonna go take naps! 00:01:16 John Host Let's go fly to Curaçao! [Jesse laughs.] Uh, no! I mean, it's—it—you know, we need a little something to get us over the darkness of the post-holiday season.