Cologne Regional Court in the Name of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nafissatou Thiam

INTERVIEW NAFISSATOU Nafissatou “Nafi” Thiam captured the World’s imagination by winning the 2016 Rio heptathlon THIAM gold medal and became the youngest ever heptathlon Olympic CAREER HIGHLIGHTS champion. She knows how to deliver on the day: her Olympic 2018 Won gold medal in the heptathlon at the gold medal came after achieving European Championship in Berlin personal best performance in five of the seven disciplines. This 2017 IAFF Female World Athlete of the Year is even more remarkable as it 2017 Gold medal in the heptathlon at London was her first Olympics! She was World Championship a flag bearer for Belgium at the 2017 Won gold medal in the pentathlon at the European Indoor Championship in Olympic closing ceremony and Belgrade continued her dominance on the world stage by winning the World 2016 Olympic gold medal in the heptathlon at Rio Olympic Games Championships and European indoor and outdoor titles. 2013 European Athletics Junior Championships in Rieti, gold medal in the heptathlon Not only is Nafi a brilliant athlete but she is also pursuing a degree in Geography at the University of Liege, Belgium. She was the Is it tough to be an elite athlete today? IAAF female athlete of the year in I think it has never been an easy job being an elite athlete. It always has – and always will - require a lot of work and sacrifice, but I guess 2017 and still is UNICEF Goodwill nowadays, with all the new technology and knowledge, there is a lot to assist athletes to reach their full (physical and mental) Ambassador for her country. -

Place Competition Cou Ntry Date Part. Score P.S. Place Result Score R.S

Cou Part. P.S. Result R.S. W.R. Comp. Place Competition Date ntry Score Place Score Place Score Score 29 AUG 1 Weltklasse, Zürich SUI 8810 1 87191 3 0 96001 2019 AG Memorial Van Damme, 06 SEP 2 BEL 8630 2 86603 7 0 95233 Boudewijnstadion, Bruxelles 2019 30 JUN 3 Prefontaine Classic, Palo Alto, CA USA 7980 4 87229 2 0 95209 2019 MO 12 JUL 4 Herculis, Stade Louis II, Monaco 7580 7 87298 1 120 94998 N 2019 05 JUL 5 Athletissima, Pontaise, Lausanne SUI 8080 3 86883 6 0 94963 2019 Müller Anniversary Games, Olympic 21 JUL 6 GBR 7635 6 86973 4 0 94608 Stadium, London 2019 Meeting de Paris, Stade Charléty, 24 AUG 7 FRA 7290 8 86968 5 0 94258 Paris 2019 Golden Gala - Pietro Mennea, Stadio 06 JUN 8 ITA 7820 5 86259 8 0 94079 Olimpico, Roma 2019 03 MAY 9 IAAF Diamond League, Doha QAT 7070 12 85682 9 0 92752 2019 IAAF Diamond League, SS, 18 MAY 10 CHN 7150 10 85311 10 0 92461 Shanghai 2019 13 JUN 11 Bislett Games, Bislett, Oslo NOR 7105 11 85146 12 0 92251 2019 Meeting International Mohammed MA 16 JUN 12 VI D'Athletisme, Prince Moulay 6855 13 85174 11 0 92029 R 2019 Abdellah, Rabat 18 AUG 13 Müller Grand Prix, Birmingham GBR 6450 14 84646 13 0 91096 2019 BAUHAUS-galan, Olympiastadion, 30 MAY 14 SWE 7160 9 83564 20 0 90724 Stockholm 2019 Gyulai István Memorial Hungarian HU 09 JUL 15 GP, Bregyó Athletic Center, 6260 15 83969 17 0 90229 N 2019 Székesfehérvár The Match Europe v USA, Dinamo 10 SEP 16 BLR 5655 16 84455 16 0 90110 National Olympic Stadium, Minsk 2019 2019 Nanjing World Challenge, 21 MAY 17 CHN 5450 17 84532 14 0 89982 Olympic Stadium, Nanjing 2019 01 SEP 18 ISTAF, Olympiastadion, Berlin GER 4430 18 84499 15 0 88929 2019 Golden Spike, Mestský Stadion, 20 JUN 19 CZE 4160 19 83951 18 0 88111 Ostrava 2019 ORLEN Memoriał Janusza 16 JUN 20 POL 3725 20 82780 23 0 86505 Kusoci ńskiego, Chorzów 2019 Paavo Nurmi Games, Paavo Nurmi, 11 JUN 21 FIN 3690 21 82636 25 0 86326 Turku 2019 08 JUN 22 Racers Grand Prix, Kingston JAM 2810 26 83006 21 0 85816 2019 23 Spitzen Leichtathletik, Luzern SUI 09 JUL 2925 24 82726 24 0 85651 Cou Part. -

Athletics Kenya Calendar of Events 2017-2018

ATHLETICS KENYA / IAAF CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR THE YEAR 2017/2018 SEASON. NOVEMBER 2017 2nd Athletics Kenya Anti-Doping Sensitization Day All Counties KEN 4th 1st Athletics Kenya Cross Country Series Nairobi KEN 4th Baringo Half Marathon Kabarnet KEN 5th Marathon des Alpes-Maritimes Nice Cannes Nice FRA 5th TSC New York Marathon New York USA 11th 2nd Athletics Kenya Cross Country Series Sotik KEN 11th Tegla Loroupe 10Km Peace Run Kapenguria KEN 12th Saitama International Marathon Saitama JPN 12th BLOM BANK Beirut Marathon Beirut LBN 12th Shangai International Marathon Shanghai CHN 12th Vodafone Istanbul Marathon Istanbul TUR 12th Kass Marathon Eldoret KEN 17th - 18th 1st A.K Track & Field Competition Moi Stadium KEN Kisumu 19th Semi- Marathon de Boulogne Billancourt Christian Granger Boulogne FRA 19th Maraton Valencia Trinidad Alfonso Valencia ESP 19th Airtel Delhi Half Marathon Delhi IND 25th Tusky’s Mattress Wareng Cross Country Eldoret KEN 25th 3rd A.K Cross Country Series Nyandarua TTC KEN 26th Marathon du Gabon GAB 26th Firenze Marathon Firenze ITA DECEMBER 2017 1st World Aids Marathon Kisumu KEN 1st - 2nd 2nd A.K Track & Field Competition Kisii KEN 3rd 71st Fukuoka International Open Marathon Championships Fukuoka JPN 3rd Standard Chartered Marathon Singapore Singapore SIN 6th AK Gala Nairobi KEN 9th 4th A.K Cross Country Series Iten KEN 10th Imenti 15Km Road Race Meru KEN 10th Guangzhou Marathon Guangzhou CHN 15th - 16th 3rd A.K Track & Field Competition Machakos KEN 17th Safaricom Kisumu City National Marathon Kisumu KEN 17th Shenzhen -

Lucy Wangui Kabuu (KEN) DOB: 24 Mar 1984

Lucy Wangui Kabuu (KEN) DOB: 24 Mar 1984 Personal Bests : Half marathon: 1:06:09 (2013); Marathon: 2:19:34 (2012); 10000m: 30:39.96 (2008) 5000m: 14:33.49 (2008) International Championships Highlights: 5000m: 3rd in 2006 CWG (Commonwealth Games) 10000m: 1st in 2006 CWG; 9 th in 2004, 7 th in 2008 Olympics Cross Country: 5 th in 2005 World Cross Country Championships Half Marathon: 4th in 2014 World Half Marathon Championships Marathon: 24 th in 2013 World Championships Progressions : Year 5000m 10000m Half Marathon Marathon 2015 1:08:51 2:20:21 2014 1:08:37 2:24:16 2013 32:44.1 1:06:09 2:44:06 2012 15:45.8 2:19:34 2011 1:07:04 2010 2009 2008 14:33.49 30:39.96 2007 14:57.55 31:32.52 Marathon career Time Race Place Date 2:20:21 Dubai 3rd 23 Jan 2015 2:24:16 Tokyo 3rd 23 Feb 2014 2:44:06 WC – Moskva 24 th 10 Aug 2013 2:22:41 Chicago 3rd 7 Oct 2012 2:23:12 London 5th 22 Apr 2012 Personal Best 2:19:34 Dubai 2nd 27 Jan 2012 DNF Osaka DNF (pace) 28 Jan 2007 2015 Results Date Race Distance Place Time 13 Sept Copenhagen Half Marathon – Kobenhavn Half marathon 3rd 1:08:51 28 Mar Sportisimo Prague Half Marathon – Praha Half marathon 6th 1:10:25 23 Jan Dubai Marathon Marathon 3rd 2:20:21 2014 Results Date Race Distance Place Time 23 Nov Delhi Half marathon Half marathon 6th 1:10:10 28 Sept Carrera La Mujer – Bogota 12Km 4th 34:43 31 May Freihofer’s Run for Women’s 5K – Albany 5Km 1st 15:21 18 May World 10K – Bangalore 10Km 1st 31:46 29 Mar World Half Marathon Championships – Kobenhavn Half marathon 4th 1:08:37 23 Feb Tokyo Marathon Marathon 3rd 2:24:16 -

IAAF DIAMOND LEAGUE MEETINGS 2016 Status Requirements and Regulations

IAAF DIAMOND LEAGUE MEETINGS 2016 Status Requirements and Regulations 1. General Principles 1.1 The IAAF Diamond League shall include the best invitational outdoor athletics meetings in the world. 1.2 Regulations governing the IAAF Diamond League shall be issued to the IAAF Diamond League Meeting Organisers (the Organiser) and may be amended every year by the IAAF, in agreement with Diamond League AG. 1.3 The precise requirements are defined hereunder. 1.4 Meeting Directors agree to respect all Rules, Regulations and decisions taken by the General Assembly of the Diamond League AG. 1.5 At least one person from the host country National Federation, selected in agreement with the Organising Committee, must be co-opted onto the Organising Committee for liaison purposes. 1.6 The IAAF Diamond League Calendar 2016 can be found in Appendix 1. 1.7 Formal Application for an IAAF Permit shall be submitted as follows: on the appropriate Application Form; countersigned by the Meeting Director and the host National Federation; by the deadline set by the IAAF. 1.8 No application shall be considered if Diamond League requirements were not met in 2015 and/or if they are not guaranteed for 2016. 2. Evaluation & Reporting 2.1 All IAAF Diamond League Meetings will undergo an annual evaluation on all aspects of their organisation following the system agreed by the Diamond League AG: level of the athletes competing, attendance of spectators; respect of these regulations; respect of all other IAAF and Diamond League Regulations (such as Television Production and Graphic Branding Guidelines); respect of the financial commitments towards the athletes; conduct of anti-doping measures; technical conduct of the competition; services provided to the athletes; Diamond League concept and office support; media services. -

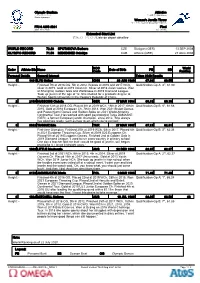

Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste De Départ Détaillée

Olympic Stadium Athletics オリンピックスタジアム 陸上競技 / Athlétisme Stade olympique Women's Javelin Throw 女子やり投 / Lancer de javelot - femmes FRI 6 AUG 2021 Final Start Time 20:50 決勝 / Finale Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste de départ détaillée WORLD RECORD 72.28 SPOTAKOVA Barbora CZE Stuttgart (GER) 13 SEP 2008 OLYMPIC RECORD 71.53 MENENDEZ Osleidys CUB Athens (GRE) 27 AUG 2004 NOC World Order Athlete Bib Name Code Date of Birth PB SB Ranking Personal Details General Interest Tokyo 2020 Results 1 1481 LYU Huihui CHN 26 JUN 1989 67.98 66.55 3 Height: - Finished 7th at 2016 OG, 5th in 2012. Bronze at 2019 and 2017 WCh, Qualification-Gp A: 3rd, 61.99 silver in 2015. Gold at 2019 Asian Ch. Silver at 2018 Asian Games. Won at Shanghai, Golden Gala and Weltklasse in 2019 Diamond League. Took up javelin at the age of 12. She studied for a graduate degree at Wuhan Sports University in the People's Republic of China. 2 2108 HUSSONG Christin GER 17 MAR 1994 69.19 69.19 2 Height: - Finished 12th at 2016 OG. Placed 4th at 2019 WCh, 16th in 2017, 6th in Qualification-Gp B: 8th, 61.68 2015. Gold at 2018 European Ch, 7th in 2014. Won 2021 Bislett Games and Paavo Nurmi Games and Golden Spike on 2021 World Athletics Continental Tour. Has worked with sport psychologist Tanja DAMASKE (GER), a former European javelin champion, since 2012. 'She always has good tips ready, such as how to act when you're excited.' 3 3662 TUGSUZ Eda TUR 27 MAR 1997 67.21 62.31 27 Height: - First-time Olympian. -

1 Athletics Kenya and International Calendar Of

ATHLETICS KENYA AND INTERNATIONAL CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR THE YEAR 2016/2017 SEASON. NOVEMBER 2016 5th 1st A.K Cross Country Series Nairobi KEN 5th Baringo Half Marathon Kabarnet KEN 6th TSC New York Marathon New York USA 6th Shangai International Marathon Shanghai CHN 12th Tegla Loroupe 10Km Peace Run Kapenguria KEN 12th 2nd A.K Cross Country Series Trans-Mara KEN 13th KASS Marathon Eldoret KEN 13th Saitama International Marathon Saitama JPN 13th Marathon des Alpes-Maritimes Nice Cannes Nice FRA 13th Cross de Atapuerca -IAAF Cross Country Permit Meetings Burgos ESP 13th Vodafone Istanbul Marathon Istanbul TUR 13th BDL Beirut Marathon Beirut LIB 19th 3rd Premium A.K Cross Country Series Nyandarua TTI KEN 20th Semi- Marathon de Boulogne Billancourt Christian Granger Boulogne FRA 20th Maraton Valencia Trinidad Alfonso Valencia ESP 20th Airtel Delhi Half Marathon Delhi IND 26th Tusky’s Mattress Wareng Cross Country Eldoret KEN 27th Cross Internacional de la Constitucion de Alcobendas -IAAF Alcobendas ESP Cross Country Permit Meetings DECEMBER 2016 1st World Aids Marathon Kisumu KEN 3rd 4th Premium A.K Cross Country Series Iten KEN 4th 70th Fukuoka International Open Marathon Championships Fukuoka JPN 4th Standard Chartered Marathon Singapore Singapore SIN 6th Campaccio-International Cross Country-IAAF Cross San Giorgio su ITA Country Permit Meetings Legnano 8th A.K Gala Nairobi KEN 11th Imenti 15Km Road Race Nkubu - Meru KEN 10th 5th Athletics Kenya Cross Country Series Kapsokwony KEN 11th Guangzhou Marathon Guangzhou CHN 14th IAAF Antrim -

2019 Media Guide

2 IAAF DiaMOND LEAGUE MEdia GUidE CONTENTS 3......................... Introduction 2019 IAAF Diamond League 4......................... Basic information – how it works, points, prize money 6......................... Calendar 7......................... Event disciplines 9......................... Host broadcasters Past seasons 10....................... Diamond Trophy winners (2010-2018) 19....................... IAAF Diamond League statistics (2010-2018) 32....................... TV reach 33....................... 2018 review Useful information 37....................... Contact details – DL AG, IAAF, IMG, meeting organisers and press chiefs 44....................... Media accreditation 3 IAAF DiaMOND LEAGUE MEdia GUidE INTRODUCTION Welcome to the 2019 season of the IAAF Diamond League. Now in its 10th year, the 2019 series will be the first that will conclude just weeks before a global championships. Athletes earn points in the first 12 meetings to qualify for two finals. As part of the overall US$8million in prize money available across the series, the finals offer a prize purse of US$3.2 million. $100,000 is at stake in each of the 32 Diamond disciplines, including $50,000 for each winner along with a stunning Diamond Trophy and a wildcard entry to the IAAF World Athletics Championships Doha 2019. In 2018, 360 million viewers from across 161 countries spanning all six continents worldwide watched the world’s top athletes compete in the IAAF Diamond League, an increase of about 78 million on the previous year. Further emphasising the IAAF Diamond League’s global credentials, athletes from 83 different countries took part in the 2018 season, with 34 of them producing winners across the series. The 2019 IAAF Diamond League – which takes place in Africa, Asia, Europe and North America – will set the scene for the world’s third-largest sporting event. -

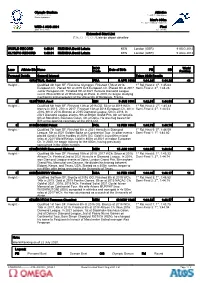

Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste De Départ Détaillée

Olympic Stadium Athletics オリンピックスタジアム 陸上競技 / Athlétisme Stade olympique Men's 800m 男子800m / 800 m - hommes WED 4 AUG 2021 Final Start Time 21:05 決勝 / Finale Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste de départ détaillée WORLD RECORD 1:40.91 RUDISHA David Lekuta KEN London (GBR) 9 AUG 2012 OLYMPIC RECORD 1:40.91 RUDISHA David Lekuta KEN London (GBR) 9 AUG 2012 NOC World Lane Athlete Bib Name Code Date of Birth PB SB Ranking Personal Details General Interest Tokyo 2020 Results 1 1978 TUAL Gabriel FRA 9 APR 1998 1:44.28 1:44.28 48 Height: - Qualified 4th from SF. First-time Olympian. Finished 17th at 2018 1st Rd, Heat 2: 3rd, 1:45.63 European Ch. Placed 5th at 2019 U23 European Ch. Placed 9th at 2017 Semi-Final 2: 3rd, 1:44.28 Junior European Ch. Finished 9th at 2021 Herculis Diamond League event. Placed 9th at 2019 Meeting de Paris. In 2019, he began studying mechanics and energetics at the University of Bordeaux, France. 2 1225 TUKA Amel BIH 9 JAN 1991 1:42.51 1:44.53 3 Height: - Qualified 6th from SF. Finished 12th at 2016 OG. Silver at 2019 WCh, 1st Rd, Heat 2: 2nd, 1:45.48 bronze in 2015, 27th in 2017. Finished 13th at 2018 European Ch, 4th in Semi-Final 3: 2nd, 1:44.53 2016, 6th in 2014. Bronze at 2015 Diamond League, 5th in 2016. In 2021 Diamond League events, 9th at British Grand Prix, 8th at Herculis, 6th at Stockholm Bauhaus Galan, 4th at Doha. -

IAAF DIAMOND LEAGUE MEETINGS 2018 Status Requirements and Regulations

IAAF DIAMOND LEAGUE MEETINGS 2018 Status Requirements and Regulations 1. General Principles 1.1 The IAAF Diamond League shall include the best invitational outdoor athletics meetings in the world. 1.2 Regulations governing the IAAF Diamond League shall be issued to the IAAF Diamond League Meeting Organisers (the Organiser) and may be amended every year by the IAAF, in agreement with Diamond League AG. 1.3 The precise requirements are defined hereunder. 1.4 Meeting Directors agree to respect all Rules, Regulations and decisions taken by the General Assembly of the Diamond League AG. 1.5 At least one person from the host country National Federation, selected in agreement with the Organising Committee, must be co-opted onto the Organising Committee for liaison purposes. 1.6 The IAAF Diamond League Calendar 2018 can be found in Appendix 1. 1.7 Formal Application for an IAAF Permit shall be submitted as follows: on the appropriate Application Form; countersigned by the Meeting Director and the host National Federation; by the deadline set by the IAAF. 1.8 No application shall be considered if Diamond League requirements were not met in 2017 and/or if they are not guaranteed for 2018. 2. Evaluation & Reporting 2.1 All IAAF Diamond League Meetings will undergo an annual evaluation on all aspects of their organisation following the system agreed by the Diamond League AG: level of the athletes competing, attendance of spectators; respect of these regulations; respect of all other IAAF and Diamond League Regulations (such as Television Production and Graphic Branding Guidelines); respect of the financial commitments towards the athletes; conduct of anti-doping measures; technical conduct of the competition; services provided to the athletes; Diamond League concept and office support; media services. -

To Download the 2015 IAAF Diamond League Media Guide (5.4Mb Pdf)

1 IAAF Diamond League 2015 media guide Contents 2......................... Introduction Diamond Race 3......................... Basic information – how it works, points, prize money 5......................... Diamond Race winners (2010-2014) 10....................... Diamond Race all-time statistics (2010-2014) 21....................... Competition review 2014 36....................... TV audiences 2015 season 37....................... Calendar 38....................... Event disciplines 40....................... Host broadcasters 41....................... Preview 42....................... Contact details – DL AG, IAAF, IMG, meeting organisers and press chiefs 48....................... Media accreditation 2 IAAF Diamond League 2015 media guide Introduction Welcome to the 2015 season of the IAAF Diamond League. During its first five seasons, the IAAF Diamond League has captured the public’s imagination like no other non-championship athletics competition. Spread across Asia, Europe, the Middle East and the USA, the 14-meeting series includes a competition programme of 32 events representing virtually the full spectrum of Olympic track and field disciplines, and offers a total of 8 million US dollars in prize money. At the core of the IAAF Diamond League is the Diamond Race with athletes battling season long to accumulate points in each of the 32 event disciplines to win a 40,000 USD cash prize, a spectacular Diamond Trophy and, having shown season-long consistency, the unchallenged honour of being their event’s world No.1. With the creation of the IAAF Diamond League in 2009, we set We look forward to working together in the next years to further out to reinvent the one-day meeting structure of our sport, to enhance the status, visibility and reach of athletics’ premier global bring clarity to the top tier of international invitational competition non-championship competition. -

World Athletics List of International Competitions 2020

World Athletics List of International Competitions 2020 For the purposes of Anti-Doping Rule 1.8 (b), the following competitions to be held in 2020 shall be considered as International Competitions (sorted by type of competition). Please note that for World Athletics Label Road Races, only Athletes with Platinum, Gold, Silver and Bronze status (as determined by World Athletics) are considered as International-Level Athletes under World Athletics Anti-Doping Rules. WORLD ATHLETICS SERIES 2020 OCT 17 World Athletics Half Marathon Championships Gdynia, POL WORLD ATHLETICS INDOOR TOUR 2020 JAN 25 New Balance Indoor Grand Prix Boston, USA 31 Indoor Meeting Karlsruhe Karlsruhe, GER FEB 04 15. Intl PSD Bank Meeting Dusseldorf Dusseldorf, GER 08 ORLEN Copernicus Cup Torun, POL 15 Müller Indoor Grand Prix Glasgow, UK 19 Meeting Hauts-de-France Pas-de-Calais Liévin, FRA 21 Villa de Madrid Madrid, ESP WORLD ATHLETICS CROSS COUNTRY PERMITS 2020 San Giorgio su JAN 06 63° Campaccio International Cross Country Legnano, ITA 12 77° Elgoibar Juan Muguerza Memorial Cross-Country Elgoibar, ESP 19 XXXVIII Cross Internacional de Italica Sevilla, ESP 26 88th Cinque Mulini San Vittore Olona, ITA FEB 02 43° Almond Blossom Cross Country Albufeira, POR TBC TBC Cross de Atapuerca Burgos, ESP TBC TBC Cross Internacional de Soria Soria, ESP TBC TBC Cross Internacional de la Constitucion Alcobendas, ESP DIAMOND LEAGUE 2020 JUN 11 Impossible Games Oslo, NOR JUL 09 Inspiration Games Zurich, SUI AUG 14 Herculis Monaco, MON AUG 23 Bauhaus-Galan Stockholm, SWE SEP 02 Athletissima