Faculty of Social Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Quality Family Health Through Adult Education Programme in Udenu, Enugu State

Promoting Quality Family Health Through Adult Education Programme in Udenu, Enugu State Matthias U. Agboeze, Michael O. Ugwueze, Maryrose N. Agboeze and Vincent N. Agbogo Department of Adult Education and Extra-Mural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Key words: Family health, adult education, health Abstract: Quality family health is the condition in which education, household hygiene family members are able to effectively carry out their duties or responsibilities in the society. Health education programme help individual members of a family to improve household hygiene so as to achieve quality family health. The objective of this study was to assess the extent adult education programmes could promote quality family health in Udenu Local Government Area of Enugu state. Descriptive survey design was used for the study. The 288 respondents from the 3 Adult Education Centers and 1 College of Education in Udenu Local Government Area of Enugu state were used for the study. The study was guided (2) research questions. The data collected from the research questions were analyzed using mean score. Instrument for data collection: A 14 item questionnaire was used to collect data for the study. The instrument was validated by three experts. Cronbach Alpha technique was used to establish the reliability before administrating the instrument to the respondents. Corresponding Author: Reliability co-efficient of 0.85 was obtained. The Michael O. Ugwueze findings, among others were that health education could Department of Adult Education and Extra-Mural Studies, improve household hygiene for achieving quality family University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria health byimproves the skill of family members on water purification processes such as chlorination. -

Prospects of Extension Services in Improving Brood and Sell Poultry Production Among Farmers in Enugu State, Nigeria

CopyrightEnvironmental © Evangeline Mbah CRIMSON PUBLISHERS C Wings to the Research Analysis & Ecology Studies ISSN 2578-0336 Review Article Prospects of Extension Services in Improving Brood and Sell Poultry Production among Farmers in Enugu State, Nigeria Jiriko R, Mbah EN* and Amah NE Department of Agricultural Extension and Communication, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Evangeline Mbah, Department of Agricultural Extension and Communication, Nigeria Submission: June 06, 2018; Published: December 21, 2018 Abstract The paper analyzed prospects of extension services in improving brood and sell poultry production among farmers in Enugu State, Nigeria. Structured interview schedule was used to collect data from a sample of fourty (40) respondents. Data were analyzed using frequency, percentage and mean scores. Results of the study showed that they were dominated by young, educated people that have acquired some experience and were extension systems and the prospects observed were still below standard of extension expectations of the recent times in some rural areas of Nigeria. Theable respondentsto finance the were small-scale highly constrained enterprise bywith high high cost net of economicfeeds and returns.raw materials The study (85.0%), further poor revealed extension a gap agents in the contact information (65.0%), service inadequate delivery drugs of Agricultural Development Programme (ADP) should integrate the activities of brood and sell poultry farmers into its programmes by providing the techniquesand veterinary involved services to contact (65.0%), farmers. high infestation Efforts of governmentof diseases (60.0%)of Enugu and State difficulty are highly in procurementneeded in subsidizing of quality the stocks inputs (62.5%). to farmers It was in orderconcluded to ensure that optimum productivity. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Assessment of Youths Involvement in Self-Help Community Development Projects in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State By

i ASSESSMENT OF YOUTHS INVOLVEMENT IN SELF-HELP COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN NSUKKA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF ENUGU STATE BY EZEMA MARCILLINUS CHIJIOKE PG/M.ED/11/58977 DEPARTMENT OF ADULT EDUCATION AND EXTRA-MURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA AUGUST, 2014. 2 ASSESSMENT OF YOUTHS INVOLVEMENT IN SELF-HELP COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN NSUKKA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF ENUGU STATE BY EZEMA MARCILLINUS CHIJIOKE PG/M.ED/11/58977 DEPARTMENT OF ADULT EDUCATION AND EXTRA-MURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA ASSOC. PROF (MRS.) F.O. MBAGWU (SUPERVISOR) AUGUST, 2014. 3 TITLE PAGE Assessment of Youths Involvement in Self-Help Community Development Projects in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State 4 APPROVAL PAGE This project has been approved for the Department of Adult Education and Extra-Mural Studies University of Nigeria, Nsukka. By _________________ _________________ Assoc. Prof (Mrs) F.O. Mbagwu Prof. P.N.C. Ngwu Supervisor Head of Department _______________ ________________ Internal Examiner External Examiner ________________________ Prof. IK. Ifelunni Dean Faculty of Education 5 CERTIFICATION Ezema M.C is a postgraduate student in the Department of Adult Education and Extra-Mural Studies with Registration Number PG/M.Ed/11/58977 and has satisfactorily completed the requirements for the course and research work for the degree of Masters in Adult Education and Community Development. The work embodied in this project is original and has not been submitted in part or full for any other diploma or degree of this university or any other university. ___________________ ___________________ Ezema, Marcillinus Chijioke Assoc. Prof (Mrs) F.O. Mbagwu Student Supervisor 6 DEDICATION This research work is dedicated to God Almighty for his mercy and protection to me throughout the period of writing this project. -

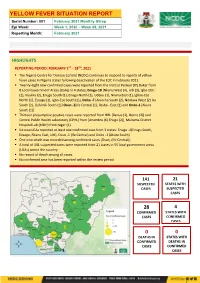

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021 HIGHLIGHTS REPORTING PERIOD: FEBRUARY 1ST – 28TH, 2021 ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) continues to respond to reports of yellow fever cases in Nigeria states following deactivation of the EOC in February 2021. ▪ Twenty -eight new confirmed cases were reported from the Institut Pasteur (IP) Dakar from 8 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in 4 states; Enugu-18 [Nkanu West (4), Udi (3), Igbo-Etiti (2), Nsukka (2), Enugu South (1), Enugu North (1), Udenu (1), Nkanu East (1), Igboe-Eze North (1), Ezeagu (1), Igbo-Eze South (1)], Delta -7 [Aniocha South (2), Ndokwa West (2) Ika South (2), Oshimili South (1)] Osun -2[Ife Central (1), Ilesha - East (1) and Ondo-1 [Akure South (1)] ▪ Thirteen presumptive positive cases were reported from NRL [Benue (2), Borno (2)] and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) from [Anambra (6) Enugu (2)], Maitama District Hospital Lab (MDH) from Niger (1) ▪ Six new LGAs reported at least one confirmed case from 3 states: Enugu -4(Enugu South, Ezeagu, Nkanu East, Udi), Osun -1 (Ife Central) and Ondo -1 (Akure South) ▪ One new death was recorded among confirmed cases [Osun, (Ife Central)] ▪ A total of 141 suspected cases were reported from 21 states in 55 local government areas (LGAs) across the country ▪ No record of death among all cases. ▪ No confirmed case has been reported within the review period 141 21 SUSPECTED STATES WITH CASES SUSPECTED CASES 28 4 -

Gender and Rural Economic Relations: Ethnography of the Nrobo of South

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2632-279X.htm Gender and Gender and rural economic rural economic relations: ethnography of the relations Nrobo of South Eastern Nigeria Ugochukwu Titus Ugwu Department of Sociology/Anthropology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Received 22 July 2020 Revised 30 November 2020 Accepted 13 December 2020 Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this study is to examine gender and rural economic relations of the Nrobo of Southeastern Nigeria. Specifically, the study was designed to examine the subsistence strategies, gendered role patterns and gender gaps in economic relations of the Nrobo. Design/methodology/approach – This study used ethnographic methods of participant observation – adopting chitchatting and semi-structured interviews. Also, focus group discussion (FGD) was used to cross- check the validity of data from the other instrument. Findings – This study found among other things, that although there is still verbal expression of gendered roles division, it does not mirror what actually obtains in society, except bio-social roles. Ideological superiority of men reflects the patrilineal kinship arrangement of society. Theoretically, some of the hypotheses of gender inequality theory were disputed for lack of adequate explanation of gender and economic relations in an egalitarian-reflected society such as Nrobo. Originality/value – This study, to the best of my knowledge, is the first attempt to ethnographically examine gender and economic relations among this group. As such it adds to the corpus of ethnographies on the Igbo of Southeastern Nigeria. Keywords Gender, Gender inequality, Ethnographic method, Gender and economic relations, Rural economic relations, Southeastern Nigeria, Gendered role patterns Paper type Research paper Introduction Issues of gender inequality have been extensively explored in relation to contemporary Western and non-Western multicultural societies. -

Niger Delta Budget Monitoring Group Mapping

CAPACITY BUILDING TRAINING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT & SHADOW BUDGETING NIGER DELTA BUDGET MONITORING GROUP MAPPING OF 2016 CAPITAL PROJECTS IN THE 2016 FGN BUDGET FOR ENUGU STATE (Kebetkache Training Group Work on Needs Assessment Working Document) DOCUMENT PREPARED BY NDEBUMOG HEADQUARTERS www.nigerdeltabudget.org ENUGU STATE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) COMMISSION S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Teaching and Learning 40,000,000 Enugu West South East New Materials in Selected Schools in Enugu West Senatorial District 2 Construction of a Block of 3 15,000,000 Udi Ezeagu/ Udi Enugu West South East New Classroom with VIP Office, Toilets and Furnishing at Community High School, Obioma, Udi LGA, Enugu State Total 55,000,000 FGGC ENUGU S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Construction of Road Network 34,264,125 Enugu- North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Enugu South 2 Construction of Storey 145,795,243 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Building of 18 Classroom, Enugu South Examination Hall, 2 No. Semi Detached Twin Buildings 3 Purchase of 1 Coastal Bus 13,000,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East Enugu South 4 Completion of an 8-Room 66,428,132 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Storey Building Girls Hostel Enugu South and Construction of a Storey Building of Prep Room and Furnishing 5 Construction of Perimeter 15,002,484 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Fencing Enugu South 6 Purchase of one Mercedes 18,656,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Water Tanker of 11,000 Litres Enugu South Capacity Total 293,145,984 FGGC LEJJA S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. -

Wellhead Protection and Quality of Well Water in Rural Communities of Udenu L.G.A of Enugu State, South Eastern Nigeria

International Journal of Geology, Agriculture and Environmental Sciences Volume – 5 Issue – 3 June 2017 Website: www.woarjournals.org/IJGAES ISSN: 2348-0254 Wellhead Protection and Quality of Well Water in Rural Communities of Udenu L.G.A of Enugu State, South Eastern Nigeria Obeta Michael Chukwuma1, Mamah Kingsley Ifeanyichukwu2 1Hydrology and Water Resources Unit,Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka Phone No = +2348132974076 2Environmental Management Unit, Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka phone +2348069271894 Abstract: Well water contamination is a major public health problem in rural Nigeria. To explore the impact of wellhead protection on well water quality and to identify possible well water contaminants, water samples were collected from twenty (ten protected and ten unprotected) wells in ten rural communities of Enugu state, southeastern Nigeria. Ten physico-chemical and bacteriological water quality parameters including Total coliform count, Escherichia coli, pH, Temperature, Ec, Turbidity, Nitrate, Chloride TDS, and Sulphate were analyzed. The values returned from the analysis of protected and unprotected well water samples were compared with each order and with WHO (2011) benchmark for drinking water. Results obtained indicated that studied wells exhibits high variations in the physico-chemical and bacteriological properties of the water samples. However, bacterial contamination in well water samples was more serious in the unprotected wells; as the Escherichia coli was detected in all samples from the unprotected wells. Contamination by physical and chemical parameters is not a serious problem in the study area. The result of the study has shown that capping is a major factor influencing bacterial contamination levels in well water of the study area. -

ANALYSIS of the PERCEPTIONS of MOTHERS on HYGIENE FACTORS AFFECTING DIARRHEA OCCURRENCE in ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA. Nwachukwu, M. C

International Journal of Public Health, Pharmacy and Pharmacology Vol. 4, No.4, pp.25-38, November 2019 Published by ECRTD-UK Print ISSN: (Print) ISSN 2516-0400 Online ISSN: (Online) ISSN 2516-0419 ANALYSIS OF THE PERCEPTIONS OF MOTHERS ON HYGIENE FACTORS AFFECTING DIARRHEA OCCURRENCE IN ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA. Nwachukwu, M. C, Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. [email protected]. Uchegbu, S. N, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus. [email protected] Okoye, C. O, Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Owing to the fact that perceptions of mothers on the hygiene factors affecting diarrhea occurrence contribute to their level of hygiene practice which may affect the incidence of diarrhea within the families, there arises the need to analyze the perception of mothers on these hygiene factors in Enugu State. The methodology adopted for the study was longitudinal survey design. Schedules were used to collect data on diarrhea among children 0-5 years from seven District Hospitals representing District Health Boards from 2007 to 2016 while questionnaire was used to collect data in respect of perceptions of mothers on hygiene factors. A total of 1110 questionnaire were administered and 1106 collected. Analysis of variance ANOVA was conducted and the study found that the perceptions of mothers on hygiene factors affecting diarrhea occurrence differ very significantly amongst the study locations (p = 0.000). Furthermore, using multiple comparison tests to detect and rank the mothers perception in the different study locations, Enugu District Health Board has the highest perception, followed by Agbani and Udi District Health Boards. -

Herbal Medicines: Alternatives to Orthodox Medicines in Ezeagu and Nsukka Communities in Enugu State, Nigeria

HERBAL MEDICINES: ALTERNATIVES TO ORTHODOX MEDICINES IN EZEAGU AND NSUKKA COMMUNITIES IN ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA Isife, Chima Theresa (Mrs.) Institute for Development Studies, Enugu Campus, University of Nigeria, Nsukka Mobile: +234-806-798-5288, Email: [email protected] Abstract Reports show that in-patient and out-patient hospital attendance declined from 45,000 in 1980 to just 25,000 in 1985. This work sought to establish the factors responsible for the dwindling patronage. A total of 255 respondents were randomly selected for the survey that used questionnaire to elicit information. Data were analyzed using simple frequencies and percentage tables. The Chi-square test was used to test the hypotheses. Findings revealed, among others, that the most common ailment in these communities is malaria, use of herbs is common in these communities, reasons for use of herbs depend on the nature of the ailment, belief in herbal option is widespread, males are more inclined to the use of herbs than women, using herbal medicine is believed to be less expensive than orthodox medicine, hospital/health centres are widely known to be available within less than 1km. Recommendations include creating awareness on efficacy of herbal medicines in order to encourgae their use, facilitating the formation of clusters among herbal practitioners for collective impact, enhancing sustainability of the commendable indigenous health practices, and craetion of databank for herbal use, healer skills and cultural resources in Nigeria. Introduction Health is an important and reoccurring issue for reason that health care delivery forms a very individuals, communities, and nations. The important aspect of any nation’s policy. -

6B JASR July 2016

JOURNAL OF APPLIED SCIENCES RESEARCH ISSN: 1819-544X Published BY AENSI Publication EISSN: 1816-157X http://www.aensiweb.com/ JASR 2016 January; 12(1): pages 49-54 Open Access Journal Poverty Alleviation and Women Cooperative Societies in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria 1Eucharia Nchedo Aye, 2Theresa Olunwa Oforka, 3Victoria Lucy Eze, 4Chiedu Eseadi 1Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. 2Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. 3Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. 4Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. Received 12 January 2016; Accepted 26 January 2016; published 28 January 2016 Address For Correspondence: Eucharia Nchedo Aye, Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected]. Copyright © 2016 by authors and American-Eurasian Network for Scientific Information (AENSI Publication). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ABSTRACT Background: Women participation in cooperative societies has been receiving serious attention in developmental circles in recent time. Moreover, in different parts of the world, cooperatives and other collective forms of economic and social enterprise have shown themselves as being distinctly beneficial to improving women’s social and economic capacities. Objective: This study aimed at examining extent women partake in the poverty alleviation and women cooperative societies in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria. Methodology: The study adopted a descriptive survey research design. All the 46 women cooperative societies and 1,380 members of the 46 registered women cooperative societies in Nsukka local government constitute the study. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694