Cerebral Phaeohyphomycosis—A Cure at What Lengths?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changes in Fungal Community Composition of Biofilms On

117: 59-77 Octubre 2016 Research article Changes in fungal community composition of biofilms on limestone across a chronosequence in Campeche, Mexico Cambios en la composición de la comunidad fúngica de biopelículas sobre roca calcárea a través de una cronosecuencia en Campeche, México Sergio Gómez-Cornelio1,4, Otto Ortega-Morales2, Alejandro Morón-Ríos1, Manuela Reyes-Estebanez2 and Susana de la Rosa-García3 ABSTRACT: 1 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Av. Ran- Background and Aims: The colonization of lithic substrates by fungal communities is determined by cho polígono 2A, Parque Industrial the properties of the substrate (bioreceptivity) and climatic and microclimatic conditions. However, the Lerma, 24500 Campeche, Mexico. effect of the exposure time of the limestone surface to the environment on fungal communities has not 2 Universidad Autónoma de Campe- been extensively investigated. In this study, we analyze the composition and structure of fungal commu- che, Departamento de Microbiología nities occurring in biofilms on limestone walls of modern edifications constructed at different times in a Ambiental y Biotecnología, Avenida subtropical environment in Campeche, Mexico. Agustín Melgar s/n, 24039 Campe- Methods: A chronosequence of walls built one, five and 10 years ago was considered. On each wall, three che, Mexico. surface areas of 3 × 3 cm of the corresponding biofilm were scraped for subsequent analysis. Fungi were 3 Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Ta- isolated by washing and particle filtration technique and were then inoculated in two contrasting culture basco, División Académica de Cien- cias Biológicas, Carretera Villahermo- media (oligotrophic and copiotrophic). The fungi were identified according to macro and microscopic sa-Cárdenas km 0.5 s/n, entronque a characteristics. -

Curvularia Keratitis*

09 Wilhelmus Final 11/9/01 11:17 AM Page 111 CURVULARIA KERATITIS* BY Kirk R. Wilhelmus, MD, MPH, AND Dan B. Jones, MD ABSTRACT Purpose: To determine the risk factors and clinical signs of Curvularia keratitis and to evaluate the management and out- come of this corneal phæohyphomycosis. Methods: We reviewed clinical and laboratory records from 1970 to 1999 to identify patients treated at our institution for culture-proven Curvularia keratitis. Descriptive statistics and regression models were used to identify variables associ- ated with the length of antifungal therapy and with visual outcome. In vitro susceptibilities were compared to the clini- cal results obtained with topical natamycin. Results: During the 30-year period, our laboratory isolated and identified Curvularia from 43 patients with keratitis, of whom 32 individuals were treated and followed up at our institute and whose data were analyzed. Trauma, usually with plants or dirt, was the risk factor in one half; and 69% occurred during the hot, humid summer months along the US Gulf Coast. Presenting signs varied from superficial, feathery infiltrates of the central cornea to suppurative ulceration of the peripheral cornea. A hypopyon was unusual, occurring in only 4 (12%) of the eyes but indicated a significantly (P = .01) increased risk of subsequent complications. The sensitivity of stained smears of corneal scrapings was 78%. Curvularia could be detected by a panfungal polymerase chain reaction. Fungi were detected on blood or chocolate agar at or before the time that growth occurred on Sabouraud agar or in brain-heart infusion in 83% of cases, although colonies appeared only on the fungal media from the remaining 4 sets of specimens. -

Curvulin and Phaeosphaeride a from Paraphoma Sp. VIZR 1.46 Isolated from Cirsium Arvense As Potential Herbicides

molecules Article Curvulin and Phaeosphaeride A from Paraphoma sp. VIZR 1.46 Isolated from Cirsium arvense as Potential Herbicides Ekaterina Poluektova 1, Yuriy Tokarev 1 , Sofia Sokornova 1 , Leonid Chisty 2, Antonio Evidente 3 and Alexander Berestetskiy 1,* 1 All-Russian Institute of Plant Protection, Podbelskogo 3, 196608 Pushkin, Russia; [email protected] (E.P.); [email protected] (Y.T.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Research Institute of Hygiene, Occupational Pathology and Human Ecology, Federal Medical Biological Agency, p/o Kuz’molovsky, 188663 Saint-Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] 3 Department of Chemical Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Complesso Universitario Monte S. Angelo, Via Cintia 4, 80126 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-(812)-4705110 Received: 8 October 2018; Accepted: 25 October 2018; Published: 28 October 2018 Abstract: Phoma-like fungi are known as producers of diverse spectrum of secondary metabolites, including phytotoxins. Our bioassays had shown that extracts of Paraphoma sp. VIZR 1.46, a pathogen of Cirsium arvense, are phytotoxic. In this study, two phytotoxically active metabolites were isolated from Paraphoma sp. VIZR 1.46 liquid and solid cultures and identified as curvulin and phaeosphaeride A, respectively. The latter is reported also for the first time as a fungal phytotoxic product with potential herbicidal activity. Both metabolites were assayed for phytotoxic, antimicrobial and zootoxic activities. Curvulin and phaeosphaeride A were tested on weedy and agrarian plants, fungi, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and on paramecia. Curvulin was shown to be weakly phytotoxic, while phaeosphaeride A caused severe necrotic lesions on all the tested plants. -

Pdf 550.92 K

Trends Phytochem. Res. 1(4) 2017 207-214 ISSN: 2588-3631 (Online) ISSN: 2588-3623 (Print) Trends in Phytochemical Research (TPR) Trends in Phytochemical Research (TPR) Volume 1 Issue 4 December 2017 © 2017 Islamic Azad University, Shahrood Branch Journal Homepage: http://tpr.iau-shahrood.ac.ir Press, All rights reserved. Original Research Article Isolation and identification of growth promoting endophytic fungi from Artemisia annua L. and its effects on artemisinin content Mir Abid Hussain1^, Vidushi Mahajan1,2^, Irshad Ahmad Rather1, Praveen Awasthi1, Rekha Chouhan1, Prabhu Dutt1, Yash Pal Sharma3, Yashbir S. Bedi1,2 and Sumit G. Gandhi1,2, 1Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine (CSIR-IIIM), Council of Scientific and Industrial esearch,R Canal Road, Jammu-180001, India 2Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research, Anusandhan Bhawan, 2 Rafi Marg, New Delhi-110 001, India 3Post Graduate Department of Botany, University of Jammu, Jammu and Kashmir, India ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone, is a well-known antimalarial drug isolated from Received: 03 July 2017 Artemisia annua L. (Asteraceae). Semi-synthetic derivatives of artemisinin like arteether, Revised: 31 August 2017 artemether, artesunate, etc. have also been explored for antimalarial as well as other Accepted: 11 October 2017 pharmacological activities. Endophytes are microorganisms which reside inside the living ePublished: 09 December 2017 tissues of host plants and can form symbiotic, parasitic or commensalistic relationship depending on the climatic conditions and host genotype. In this study, endophytic fungi KEYWORDS were isolated from the leaves of A. annua and were identified using the conventional as well as molecular taxonomic methods. Endophytes were identified as: Colletotrichum Acremonium persicum gloeosporioides, Cochliobolus lunatus, Curvularia pallescens and Acremonium persicum. -

Monograph on Dematiaceous Fungi

Monograph On Dematiaceous fungi A guide for description of dematiaceous fungi fungi of medical importance, diseases caused by them, diagnosis and treatment By Mohamed Refai and Heidy Abo El-Yazid Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University 2014 1 Preface The first time I saw cultures of dematiaceous fungi was in the laboratory of Prof. Seeliger in Bonn, 1962, when I attended a practical course on moulds for one week. Then I handled myself several cultures of black fungi, as contaminants in Mycology Laboratory of Prof. Rieth, 1963-1964, in Hamburg. When I visited Prof. DE Varies in Baarn, 1963. I was fascinated by the tremendous number of moulds in the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, Netherlands. On the other hand, I was proud, that El-Sheikh Mahgoub, a Colleague from Sundan, wrote an internationally well-known book on mycetoma. I have never seen cases of dematiaceous fungal infections in Egypt, therefore, I was very happy, when I saw the collection of mycetoma cases reported in Egypt by the eminent Egyptian Mycologist, Prof. Dr Mohamed Taha, Zagazig University. To all these prominent mycologists I dedicate this monograph. Prof. Dr. Mohamed Refai, 1.5.2014 Heinz Seeliger Heinz Rieth Gerard de Vries, El-Sheikh Mahgoub Mohamed Taha 2 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. 30. The genus Rhinocladiella 83 2. Description of dematiaceous 6 2. 31. The genus Scedosporium 86 fungi 2. 1. The genus Alternaria 6 2. 32. The genus Scytalidium 89 2.2. The genus Aurobasidium 11 2.33. The genus Stachybotrys 91 2.3. The genus Bipolaris 16 2. -

Fungal Allergy and Pathogenicity 20130415 112934.Pdf

Fungal Allergy and Pathogenicity Chemical Immunology Vol. 81 Series Editors Luciano Adorini, Milan Ken-ichi Arai, Tokyo Claudia Berek, Berlin Anne-Marie Schmitt-Verhulst, Marseille Basel · Freiburg · Paris · London · New York · New Delhi · Bangkok · Singapore · Tokyo · Sydney Fungal Allergy and Pathogenicity Volume Editors Michael Breitenbach, Salzburg Reto Crameri, Davos Samuel B. Lehrer, New Orleans, La. 48 figures, 11 in color and 22 tables, 2002 Basel · Freiburg · Paris · London · New York · New Delhi · Bangkok · Singapore · Tokyo · Sydney Chemical Immunology Formerly published as ‘Progress in Allergy’ (Founded 1939) Edited by Paul Kallos 1939–1988, Byron H. Waksman 1962–2002 Michael Breitenbach Professor, Department of Genetics and General Biology, University of Salzburg, Salzburg Reto Crameri Professor, Swiss Institute of Allergy and Asthma Research (SIAF), Davos Samuel B. Lehrer Professor, Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA Bibliographic Indices. This publication is listed in bibliographic services, including Current Contents® and Index Medicus. Drug Dosage. The authors and the publisher have exerted every effort to ensure that drug selection and dosage set forth in this text are in accord with current recommendations and practice at the time of publication. However, in view of ongoing research, changes in government regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to drug therapy and drug reactions, the reader is urged to check the package insert for each drug for any change in indications and dosage and for added warnings and precautions. This is particularly important when the recommended agent is a new and/or infrequently employed drug. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated into other languages, reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, microcopy- ing, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Culture Inventory

For queries, contact the SFA leader: John Dunbar - [email protected] Fungal collection Putative ID Count Ascomycota Incertae sedis 4 Ascomycota Incertae sedis 3 Pseudogymnoascus 1 Basidiomycota Incertae sedis 1 Basidiomycota Incertae sedis 1 Capnodiales 29 Cladosporium 27 Mycosphaerella 1 Penidiella 1 Chaetothyriales 2 Exophiala 2 Coniochaetales 75 Coniochaeta 56 Lecythophora 19 Diaporthales 1 Prosthecium sp 1 Dothideales 16 Aureobasidium 16 Dothideomycetes incertae sedis 3 Dothideomycetes incertae sedis 3 Entylomatales 1 Entyloma 1 Eurotiales 393 Arthrinium 2 Aspergillus 172 Eladia 2 Emericella 5 Eurotiales 2 Neosartorya 1 Paecilomyces 13 Penicillium 176 Talaromyces 16 Thermomyces 4 Exobasidiomycetes incertae sedis 7 Tilletiopsis 7 Filobasidiales 53 Cryptococcus 53 Fungi incertae sedis 13 Fungi incertae sedis 12 Veroneae 1 Glomerellales 1 Glomerella 1 Helotiales 34 Geomyces 32 Helotiales 1 Phialocephala 1 Hypocreales 338 Acremonium 20 Bionectria 15 Cosmospora 1 Cylindrocarpon 2 Fusarium 45 Gibberella 1 Hypocrea 12 Ilyonectria 13 Lecanicillium 5 Myrothecium 9 Nectria 1 Pochonia 29 Purpureocillium 3 Sporothrix 1 Stachybotrys 3 Stanjemonium 2 Tolypocladium 1 Tolypocladium 2 Trichocladium 2 Trichoderma 171 Incertae sedis 20 Oidiodendron 20 Mortierellales 97 Massarineae 2 Mortierella 92 Mortierellales 3 Mortiererallales 2 Mortierella 2 Mucorales 109 Absidia 4 Backusella 1 Gongronella 1 Mucor 25 RhiZopus 13 Umbelopsis 60 Zygorhynchus 5 Myrmecridium 2 Myrmecridium 2 Onygenales 4 Auxarthron 3 Myceliophthora 1 Pezizales 2 PeZiZales 1 TerfeZia 1 -

Phialemonium Obovatum Keratitis After Penetration Injury of the Cornea

Korean J Ophthalmol 2012;26(6):465-468 http://dx.doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2012.26.6.465 pISSN: 1011-8942 eISSN: 2092-9382 Case Report Phialemonium obovatum Keratitis after Penetration Injury of the Cornea Kwon Ho Hong1, Nam Hee Ryoo2, Sung Dong Chang1 1Department of Ophthalmology, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea Phialemonium keratitis is a very rare case and we encountered a case of keratitis caused by Phialemonium obo- vatum (P. obovatum) after penetrating injury to the cornea. This is the first case report in the existing literature. A 54-year-old male was referred to us after a penetration injury, and prompt primary closure was performed. Two weeks after surgery, an epithelial defect and stromal melting were observed near the laceration site. P. obo- vatum was identified, and then identified again on repeated cultures. Subsequently, Natacin was administered every two hours. Amniotic membrane transplantation was performed due to a persistent epithelial defect and impending corneal perforation. Three weeks after amniotic membrane transplantation, the epithelial defect had completely healed, but the cornea had turned opaque. Six months after amniotic membrane transplantation, visual acuity was light perception only, and corneal thinning and diffuse corneal opacification remained opaque. Six months after amniotic membrane transplantation, visual acuity was light perception only, and corneal thin- ning and diffuse corneal opacification remained. Key Words: Corneal ulcer, Fungi, Phialemonium obovatum Members of the Phialemonium genus are dematiaceous Case Report fungi, which are known as causative fungi for opportunis- tic infection in immunocompromised hosts. -

Australia Biodiversity of Biodiversity Taxonomy and and Taxonomy Plant Pathogenic Fungi Fungi Plant Pathogenic

Taxonomy and biodiversity of plant pathogenic fungi from Australia Yu Pei Tan 2019 Tan Pei Yu Australia and biodiversity of plant pathogenic fungi from Taxonomy Taxonomy and biodiversity of plant pathogenic fungi from Australia Australia Bipolaris Botryosphaeriaceae Yu Pei Tan Curvularia Diaporthe Taxonomy and biodiversity of plant pathogenic fungi from Australia Yu Pei Tan Yu Pei Tan Taxonomy and biodiversity of plant pathogenic fungi from Australia PhD thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands (2019) ISBN: 978-90-393-7126-8 Cover and invitation design: Ms Manon Verweij and Ms Yu Pei Tan Layout and design: Ms Manon Verweij Printing: Gildeprint The research described in this thesis was conducted at the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Ecosciences Precinct, 41 Boggo Road, Dutton Park, Queensland, 4102, Australia. Copyright © 2019 by Yu Pei Tan ([email protected]) All rights reserved. No parts of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any other forms by any means, without the permission of the author, or when appropriate of the publisher of the represented published articles. Front and back cover: Spatial records of Bipolaris, Curvularia, Diaporthe and Botryosphaeriaceae across the continent of Australia, sourced from the Atlas of Living Australia (http://www.ala. org.au). Accessed 12 March 2019. Taxonomy and biodiversity of plant pathogenic fungi from Australia Taxonomie en biodiversiteit van plantpathogene schimmels van Australië (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 9 mei 2019 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Yu Pei Tan geboren op 16 december 1980 te Singapore, Singapore Promotor: Prof. -

Glimpses of Antimicrobial Activity of Fungi from World

Journal on New Biological Reports 2(2): 142-162 (2013) ISSN 2319 – 1104 (Online) Glimpses of antimicrobial activity of fungi from World Kiran R. Ranadive 1* Mugdha H. Belsare 2, Subhash S. Deokule 2, Neeta V. Jagtap 1, Harshada K. Jadhav 1 and Jitendra G. Vaidya 2 1Waghire College, Saswad, Pune – 411 055, Maharashtra, India 2Department of Botany, University of Pune, Pune (Received on: 17 April, 2013; accepted on: 12 June, 2013) ABSTRACT As we all know that certain mushrooms and several other fungi show some novel properties including antimicrobial properties against bacteria, fungi and protozoan’s. These properties play very important role in the defense against several severe diseases caused by bacteria, fungi and other organisms also. In the available recent literature survey, many interesting observations have been made regarding antimicrobial activity of fungi. In particular this study shows total 316 species of 150 genera from 64 Fungal families (45 Basidiomycetous and 21 Ascomycetous families {6 Lichenized, 15 Non-Lichenized and 3 Incertae sedis)} are reported so far from world showing antibacterial activity against 32 species of 18 genera of bacteria and 22 species of 13 genera of fungi. This data materialistically adds the hidden potential of these reported fungi and it also clears the further line of action for the study of unknown medicinal fungi useful in human life. Key Words: Fungi, antimicrobial activity, microbes INTRODUCTION Fungi and animals are more closely related to one In recent in vitro study, extracts of more than 75 another than either is to plants, diverging from plants percent of polypore mushroom species surveyed more than 460 million years ago (Redecker 2000). -

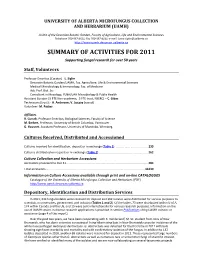

University of Alberta Microfungus Collection and Herbarium (Uamh)

UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA MICROFUNGUS COLLECTION AND HERBARIUM (UAMH) A Unit of the Devonian Botanic Garden, Faculty of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences Telephone 780‐987‐4811; Fax 780‐987‐4141; e‐mail: [email protected] http://www.uamh.devonian.ualberta.ca SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES FOR 2011 Supporting fungal research for over 50 years Staff, Volunteers Professor Emeritus (Curator) ‐ L. Sigler Devonian Botanic Garden/UAMH, Fac. Agriculture, Life & Environmental Sciences Medical Microbiology & Immunology, Fac. of Medicine Adj. Prof. Biol. Sci. Consultant in Mycology, PLNA/UAH Microbiology & Public Health Assistant Curator (.5 FTE Non‐academic, .5 FTE trust, NSERC) – C. Gibas Technicians (trust): ‐ A. Anderson; V. Jajczay (casual) Volunteer‐ M. Packer Affiliates R. Currah, Professor Emeritus, Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science M. Berbee, Professor, University of British Columbia, Vancouver G. Hausner, Assistant Professor, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg Cultures Received, Distributed and Accessioned Cultures received for identification, deposit or in exchange (Table 1) ....................................... 233 Cultures distributed on request or in exchange (Table 2)............................................................ 262 Culture Collection and Herbarium Accessions Accessions processed to Dec 31. .................................................................................................. 284 Total accessions....................................................................................................................... -

Taxonomic Re-Examination of Nine Rosellinia Types (Ascomycota, Xylariales) Stored in the Saccardo Mycological Collection

microorganisms Article Taxonomic Re-Examination of Nine Rosellinia Types (Ascomycota, Xylariales) Stored in the Saccardo Mycological Collection Niccolò Forin 1,* , Alfredo Vizzini 2, Federico Fainelli 1, Enrico Ercole 3 and Barbara Baldan 1,4,* 1 Botanical Garden, University of Padova, Via Orto Botanico, 15, 35123 Padova, Italy; [email protected] 2 Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection (IPSP-SS Torino), C.N.R., Viale P.A. Mattioli, 25, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Torino, Viale P.A. Mattioli, 25, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Biology, University of Padova, Via Ugo Bassi, 58b, 35131 Padova, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.F.); [email protected] (B.B.) Abstract: In a recent monograph on the genus Rosellinia, type specimens worldwide were revised and re-classified using a morphological approach. Among them, some came from Pier Andrea Saccardo’s fungarium stored in the Herbarium of the Padova Botanical Garden. In this work, we taxonomically re-examine via a morphological and molecular approach nine different Rosellinia sensu Saccardo types. ITS1 and/or ITS2 sequences were successfully obtained applying Illumina MiSeq technology and phylogenetic analyses were carried out in order to elucidate their current taxonomic position. Only the Citation: Forin, N.; Vizzini, A.; ITS1 sequence was recovered for Rosellinia areolata, while for R. geophila, only the ITS2 sequence was Fainelli, F.; Ercole, E.; Baldan, B. recovered. We proposed here new combinations for Rosellinia chordicola, R. geophila and R. horridula, Taxonomic Re-Examination of Nine R. ambigua R.