2 – Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

FICTIONAL NARRATIVE WRITING RUBRIC 4 3 2 1 1 Organization

FICTIONAL NARRATIVE WRITING RUBRIC 4 3 2 1 1 The plot is thoroughly Plot is adequately The plot is minimally The story lacks a developed Organization: developed. The story is developed. The story has developed. The story plot line. It is missing either a interesting and logically a clear beginning, middle does not have a clear beginning or an end. The organized: there is clear and end. The story is beginning, middle, and relationship between the exposition, rising action and arranged in logical order. end. The sequence of events is often confusing. climax. The story has a clear events is sometimes resolution or surprise confusing and may be ending. hard to follow. 2 The setting is clearly The setting is clearly The setting is identified The setting may be vague or Elements of Story: described through vivid identified with some but not clearly described. hard to identify. Setting sensory language. sensory language. It has minimal sensory language. 3 Major characters are well Major and minor Characters are minimally Main characters are lacking Elements of Story: developed through dialogue, characters are somewhat developed. They are development. They are Characters actions, and thoughts. Main developed through described rather than described rather than characters change or grow dialogue, actions, and established through established. They lack during the story. thoughts. Main dialogue, actions and individuality and do not change characters change or thoughts. They show little throughout the story. grow during the story. growth or change during the story. 4 All dialogue sounds realistic Most dialogue sounds Some dialogue sounds Dialogue may be nonexistent, Elements of Story: and advances the plot. -

REFERENCE DOCUMENT Containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE

REFERENCE DOCUMENT containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE The Lagardère group is a global leader in content publishing, production, broadcasting and distribution, whose powerful brands leverage its virtual and physical networks to attract and enjoy qualifi ed audiences. The Group’s business model relies on creating a lasting and exclusive relationship between the content it offers and its customers. It is structured around four business divisions: • Books and e-Books: Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion, and Foodservice: Lagardère Travel Retail • Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage: Lagardère Active • Sponsorship, Content, Consulting, Events, Athletes, Stadiums, Shows, Venues and Artists: Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945: at the end of World 1986: Hachette regains 26 March 2003: War II, Marcel Chassagny founds control of Europe 1. Arnaud Lagardère is appointed Matra (Mécanique Aviation Managing Partner of TRAction), a company focused 10 February 1988: Lagardère SCA. on the defence industry. Matra is privatised. 2004: the Group acquires 1963: Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 December 1992: a portion of Vivendi Universal becomes Chief Executive Publishing’s French and following the failure of French Offi cer of Matra, which Spanish assets. television channel La Cinq, has diversifi ed into aerospace Hachette is merged into Matra and automobiles. to form Matra-Hachette, 2007: the Group reorganises and Lagardère Groupe, a French around four major institutional 1974: Sylvain Floirat asks partnership limited by shares, brands: Lagardère Publishing, Jean-Luc Lagardère to head is created as the umbrella Lagardère Services (which the Europe 1 radio network. company for the entire became Lagardère Travel Retail ensemble. -

Stephen Colbert's Super PAC and the Growing Role of Comedy in Our

STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE BY MELISSA CHANG, SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS ADVISER: CHRIS EDELSON, PROFESSOR IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS UNIVERSITY HONORS IN CLEG SPRING 2012 Dedicated to Professor Chris Edelson for his generous support and encouragement, and to Professor Lauren Feldman who inspired my capstone with her course on “Entertainment, Comedy, and Politics”. Thank you so, so much! 2 | C h a n g STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE Abstract: Comedy plays an increasingly legitimate role in the American political discourse as figures such as Stephen Colbert effectively use humor and satire to scrutinize politics and current events, and encourage the public to think more critically about how our government and leaders rule. In his response to the Supreme Court case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) and the rise of Super PACs, Stephen Colbert has taken the lead in critiquing changes in campaign finance. This study analyzes segments from The Colbert Report and the Colbert Super PAC, identifying his message and tactics. This paper aims to demonstrate how Colbert pushes political satire to new heights by engaging in real life campaigns, thereby offering a legitimate voice in today’s political discourse. INTRODUCTION While political satire is not new, few have mastered this art like Stephen Colbert, whose originality and influence have catapulted him to the status of a pop culture icon. Never breaking character from his zany, blustering persona, Colbert has transformed the way Americans view politics by using comedy to draw attention to important issues of the day, critiquing and unpacking these issues in a digestible way for a wide audience. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Fiction As Research Practice: Short Stories, Novellas, and Novels

Alberta Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 62.1, Spring 2016, 130-133 Book Review Fiction as Research Practice: Short Stories, Novellas, and Novels Patricia Leavy Walnut, CA: Left Coast Press Inc., 2013 Reviewed by: Frances Kalu University of Calgary Fiction as Research Practice: Short Stories, Novellas, and Novels introduces the reader to fiction-based research. In the first section, Patricia Leavy explores the genre by explaining its background and possibilities and goes on to describe how to conduct and evaluate fiction-based research. In the second section of the book, she presents and evaluates examples of fiction-based research in different forms including short stories and excerpts from novellas and novels written by different authors. The third and final section explains how fiction and fiction-based research can be used in teaching. Leavy clearly differentiates the term fiction-based research from arts- based research in order to project the emergent field in a clear light of its own. Babbie (2001) explains that just as qualitative research practice emerged as a means of explaining phenomena that could not be captured by quantitative scientific research, social research attempts to study and understand everyday life experiences. Within social research, arts-based research tries to represent phenomena studied aesthetically through various forms of art (Barone & Eisner, 2012). As a form of arts-based research, Leavy describes fiction-based research as a great way to explore “topics that can be difficult to approach” through fiction (p. 20). Topics include the intricacies of interactions in everyday life, race relations, and socio-economic class and its effects on human life. -

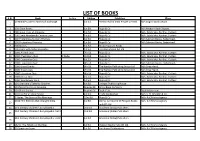

List of Books S.N

LIST OF BOOKS S.N. Book Author Edition Publisher Place 10 Minute Guide to Microsoft Exchange. 1st Ed. Prentic-Hall of India Private Limited. M/s English Book Depot 1 2 100 Great Books. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Modern Book Depote, 3 100 Great Lives of Antiquity. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 4 100 Great Nineteenth Century Lives. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 5 100 Pretentious Nursery Rhymes. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 6 100 Pretentious Proverbs. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 7 100 Stories. 1st Ed. Better Yourself Books 8 100 Years with Nobel Laureates. 1st Ed. I K International Pvt Ltd 9 1000 Animal Quiz. 7th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 10 1000 Chemistery Quiz. C Dube 3rd Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 11 1000 Economics Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 12 1000 Economics Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 13 1000 Great Events. 6th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 14 1000 Great Lives. 7th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 15 1000 Literature Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 16 1000 Orissa Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 17 1000 Wordpower Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 18 101 Grandma's Tales for Children. 1st Ed. Dhingra Publishing House 19 101 Moral Stories of Grandpa. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Great Historical Fiction Books at the Pleasanton Public Library

Dangerous Crossing by Stephen Krensky 1605 to 1750 1750 to 1830 Shelved in Children’s Moving Up Grades 2-5 Audiobook available Blood on the River: James Town 1607 Great Historical by Laurie Halse Anderson In 1778, ten-year-old Johnny Adams and his by Elisa Carbone Chains Grades 7-10 (320 p) Audiobook available father make a dangerous mid-winter voyage Grades 5-8 (237 p) from Massachusetts to Paris in hopes of Traveling to the New World in 1606 as the page to After being sold to a cruel couple in New York City, a slave named Isabel spies for the rebels during the gaining support for the colonies during the Fiction Books Captain John Smith, twelve-year-old orphan Samuel American Revolution. Collier settles in the new colony of James Town, where Revolutionary War. he must quickly learn to distinguish between friend and Hannah Pritchard: A Pirate of the Revolution at the foe. Fever, 1793 by Laurie Halse Anderson by Bonnie Pryor Grades 7-10 (251 p) Audiobook available Grades 5-7 (160 p) Historical Fiction Adventures series The Sacrifice by Kathleen B. Duble The year is 1793 and fourteen-year-old Matilda After her parents and brother are killed by Loyalists, Grades 6-9 (211 p) Cook finds herself in the middle of a struggle to fourteen-year-old Hannah leaves their farm and eventually, Pleasanton Two sisters, aged ten and twelve, are accused of keep herself and her loved ones alive in the midst disguised as a boy, joins a pirate ship that preys on other ships witchcraft in Andover, Massachusetts, in 1692 and await of the yellow fever epidemic. -

A Genre Is a Conventional Response to a Rhetorical Situation That Occurs Fairly Often

What is a genre? A genre is a conventional response to a rhetorical situation that occurs fairly often. Conventional does not necessarily mean boring. Instead, it means a recognizable pattern for providing specific kinds of information for an identifiable audience demanded by circumstances that come up again and again. For example, new movies open almost every week. Movie makers pay for advertising to entice viewers to see their movies. Genres have a purpose. While consumers may learn about a movie from the ads, they know they are getting a sales pitch with that information, so they look for an outside source of information before they spend their money. Movie reviews provide viewers with enough information about the content and quality of a film to help them make a decision, without ruining it for them by giving away the ending. Movie reviews are the conventional response to the rhetorical situation of a new film opening. Genres have a pattern. The movie review is conventional because it follows certain conventions, or recognized and accepted ways of giving readers information. This is called a move pattern. Here are the moves associated with that genre: 1. Name of the movie, director, leading actors, Sometimes, the opening also includes the names of people and companies associated with the film if that information seems important to the reader: screenwriter, animators, special effects, or other important aspects of the film. This information is always included in the opening lines or at the top of the review. 2. Graphic design elements---usually, movie reviews include some kind of art or graphic taken from the film itself to call attention to the review and draw readers into it.