Optimizing Skin and Coat Condition in the Dog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T O Have and Maintain a Good, Strong, Healthy Corded

o have and maintain a good, strong , healthy corded When bathing a fully corded coat, one must allow time for T coat there are several things that must come the bath, the rinsing (which can take longer than the actual together .. .. Genetics, nutrition, health of the dog and care bathing) and, of course, drying. Always put the given by the owner(s). shampoo into lukewarm water first... being sure it is mixed well ..then add the dog . (Only use as much shampoo as is There are many types of corded Puli coats ... thick and lush, absolutely necessary to get the job done. Too much and sparse and wispy, wiry, soft, black, gray, white, etc. the suds will be impossible to get rid of.) With a fully corded However, it must be understood that not all Puli coats are coat, it can take some time for the cords to get completely created equal. Genetics play a huge part in determining wet. As the cords float to the top , keep pushing them down what type of coat a particular dog will have at maturity. into the water. With the dog lying in the tub, I continually However, it is up to the owner to see to it that the dog is pour the soapy water over the dog .. being careful not to get kept free of parasites, is fed a well balanced diet, gets the water in the eyes/ears/mouth ... squeezing the coat like plenty of exercise and keeps his dog as clean as possible. one would a sweater. This process can take up to fifteen Often the best advice comes from the individual breeder. -

Dog Coat Colour Genetics: a Review Date Published Online: 31/08/2020; 1,2 1 1 3 Rashid Saif *, Ali Iftekhar , Fatima Asif , Mohammad Suliman Alghanem

www.als-journal.com/ ISSN 2310-5380/ August 2020 Review Article Advancements in Life Sciences – International Quarterly Journal of Biological Sciences ARTICLE INFO Open Access Date Received: 02/05/2020; Date Revised: 20/08/2020; Dog Coat Colour Genetics: A Review Date Published Online: 31/08/2020; 1,2 1 1 3 Rashid Saif *, Ali Iftekhar , Fatima Asif , Mohammad Suliman Alghanem Authors’ Affiliation: 1. Institute of Abstract Biotechnology, Gulab Devi Educational anis lupus familiaris is one of the most beloved pet species with hundreds of world-wide recognized Complex, Lahore - Pakistan breeds, which can be differentiated from each other by specific morphological, behavioral and adoptive 2. Decode Genomics, traits. Morphological characteristics of dog breeds get more attention which can be defined mostly by 323-D, Town II, coat color and its texture, and considered to be incredibly lucrative traits in this valued species. Although Punjab University C Employees Housing the genetic foundation of coat color has been well stated in the literature, but still very little is known about the Scheme, Lahore - growth pattern, hair length and curly coat trait genes. Skin pigmentation is determined by eumelanin and Pakistan 3. Department of pheomelanin switching phenomenon which is under the control of Melanocortin 1 Receptor and Agouti Signaling Biology, Tabuk Protein genes. Genetic variations in the genes involved in pigmentation pathway provide basic understanding of University - Kingdom melanocortin physiology and evolutionary adaptation of this trait. So in this review, we highlighted, gathered and of Saudi Arabia comprehend the genetic mutations, associated and likely to be associated variants in the genes involved in the coat color and texture trait along with their phenotypes. -

Stopping the Scales, Greasiness and Odor of Seborrhea in Shelter and Foster Home Dogs

Stopping the Scales, Greasiness and Odor of Seborrhea in Shelter and Foster Home Dogs Webcast Transcript May 2015 This transcript has been automatically generated and may not be 100% accurate. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Maddie’s Institute® programming is the audio. [Beginning of Audio] Lynne Fridley: Good evening everyone. Thank you for being here for the third installment in our webcast series on dermatology, "Stopping the Scales, Greasiness, and Odor of Seborrhea in Shelter and Foster Home Dogs.” I'm Lynne Fridley, Program Manager for Maddie's Institute®. Our speaker tonight is Dr. Karen Moriello, a clinical professor of veterinary dermatology at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin—Madison, where she's been a faculty member since 1986. Before we start, let's talk about a few housekeeping items. Please take a look at the left side of your screen where you'll see a Q and A window. That's where you'll ask questions during the presentation. Don't hold them until the end. Questions asked in the last few minutes will probably not be processed in time for a response. If you need help with your connection, during the presentation, you can click on the help widget on the bottom of your screen. The green file widget contains the presentation handout and a printable certificate of attendance for people attending this live event. So be sure to download, save, and print. For veterinarians and vet techs, your certificate of attendance will be emailed within two weeks of this presentation. -

The Dog Buyer's Guide

THE DOG BUYER’S GUIDE The Society for Canine Genetic Health and Ethics www.koiranjalostus.fi Foreword The main purpose of the A dog is a living creature We hope you will find this guidebook is to provide and no one can guarantee that guide useful in purchasing help for anyone planning your dog will be healthy and your dog! the purchase of his or her flawless. Still, it pays to choose first dog. However, it can be a breeder who does his best useful for anyone planning to guarantee it. We hope this to get a dog. Our aim is to guide will help you to actively help you and your family to and critically find and process choose a dog that best suits information about the health, your needs and purposes. characteristics and behaviour of the breed or litter of your Several breeds seem to be choice. plagued with health and character problems. The This guide has been created, Finnish Society for Canine written and constructed by Genetic Health and Ethics the members of the HETI (HETI) aims to influence society: Hanna Bragge, Päivi dog breeding by means of Jokinen, Anitta Kainulainen, information education. Our Inkeri Kangasvuo, Susanna aim is to see more puppies Kangasvuo, Tiina Karlström, born to this world free of Pertti Kellomäki, Sara genetic disorders that would Kolehmainen, Saija Lampinen, deteriorate their quality of life Virpi Leinonen, Helena or life-long stress caused by, Leppäkoski, Anna-Elisa for example, defects in the Liinamo, Mirve Liius, Eira nervous system. Malmstén, Erkki Mäkelä, Katariina Mäki, Anna Niiranen, The demand of puppies is Tiina Notko, Riitta Pesonen, one of the most important Meri Pisto koski, Maija factors that guides the dog Päivärinta, Johanna Rissanen, breeding. -

About Cooper

DISCOVER ALL ABOUT COOPER The results are in! Let's take a look at what the DNA told us about Cooper's ancestry... © 2019 Mars, Incorporated and its Affiliates. COOPER'S BREED BY PERCENTAGE 75% Great Pyrenees 25% Golden Retriever Exciting news, the results are in! Here’s what makes Cooper so unique. Using the data generated from Cooper’s DNA, our sophisticated computer algorithm performed over 17 million calculations! What you see here is Cooper's ancestry by percentage. GREAT PYRENEES THEY HAVE EXISTED FOR SEVERAL MILLENNIA. Intelligent, watchful, and generally calm dogs. Great Pyrenees seem to enjoy dog sports such as agility, tracking and competitive obedience as well as hiking, backpacking and carting. Independent spirit but responds well to a reward-based approach to training involving treats or favorite toys. Can be standoffish and wary with strangers and has a tendency to bark. Height 25 - 27 in Weight (show) 80 - 120 lb Weight (pet) 66 - 138 lb DID YOU KNOW? Rumor has it this breed is so old they are literally fossilized. Certainly many agree that they have existed for several millennia, possibly even dating as far back as 1800 BC. Their assumed direct ancestors include the Kuvasz, the Maremma Sheepdog and the Anatolian Shepherd. Eventually the breed was brought to Europe, and the Pyrenees mountains, where they were renowned as great herders. During the 1600s, Louis XIV declared these gentle and affectionate souls to be the Royal Dog of France. They were first brought to America in the early 19th century but numbers fell significantly after that. -

Winter-Proof Your Pooch

POOCH NEWS Edition 08 / 2012 1.866.933.5111 www.ThePoochMobile.us Winter-Proof Your Pooch Ice Melt When dogs go outside they can pick up rock salt, ice, and chemical ice melt in the pads of Winter can be Medicated shampoos and other treatments can their feet. Wipe their feet and check their legs such a beautiful alleviate some itching while also helping to treat and belly to ensure it is ice and chemical free. time of year infections. Supplements rich in Omega 3 fatty Dry them off when they come inside. They will and a fun acids may also help to maintain a dog’s healthy quickly get used to this routine and it will also time to spend skin. keep your house cleaner. with the entire family, both Humidifiers can be especially helpful in homes Senior Pets indoors and with ducted or fan forced heaters that tend to Senior pets need some extra TLC during the out. However be especially drying to a dog’s skin. cold weather days. Their joints may become the winter can Talk with your Pooch Mobile operator today super sensitive and tender. Eliminate as many affect our dogs about the unique range of Pooch Mobile dog stairs as possible in your home or walk behind just as much as it can affect us, especially on shampoos. Pooch Mobile shampoos are soap them when they climb stairs or hills in case they those cold and dreary days when the outdoors free, hypoallergenic and PH balanced for dog’s slip. Keep their bedding in a warm, draft free is less than inviting for walks and playtime. -

Best in Grooming Best in Show

Best in Grooming Best in Show crownroyaleltd.net About Us Crown Royale was founded in 1983 when AKC Breeder & Handler Allen Levine asked his friend Nick Scodari, a formulating chemist, to create a line of products that would be breed specific and help the coat to best represent the breed standard. It all began with the Biovite shampoos and Magic Touch grooming sprays which quickly became a hit with show dog professionals. The full line of Crown Royale grooming products followed in Best in Grooming formulas to meet the needs of different coat types. Best in Show Current owner, Cindy Silva, started work in the office in 1996 and soon found herself involved in all aspects of the company. In May 2006, Cindy took full ownership of Crown Royale Ltd., which continues to be a family run business, located in scenic Phillipsburg, NJ. Crown Royale Ltd. continues to bring new, innovative products to professional handlers, groomers and pet owners worldwide. All products are proudly made in the USA with the mission that there is no substitute for quality. Table of Contents About Us . 2 How to use Crown Royale . 3 Grooming Aids . .3 Biovite Shampoos . .4 Shampoos . .5 Conditioners . .6 Finishing, Grooming & Brushing Sprays . .7 Dog Breed & Coat Type . 8-9 Powders . .10 Triple Play Packs . .11 Sporting Dog . .12 Dilution Formulas: Please note when mixing concentrate and storing them for use other than short-term, we recommend mixing with distilled water to keep the formulas as true as possible due to variation in water make-up throughout the USA and international. -

Grooming a Welsh Springer Spaniel for Pet Or Show by Sandy Roth

Grooming A Welsh Springer Spaniel For Pet Or Show By Sandy Roth Webmaster Note: This article was published in "The Starter Barks", Volume 45, Issue 2, June 2008. If you are fortunate enough to get your Welshie as a puppy you can gently expose the new puppy to the many facets of grooming. By spending 5 minutes a day over several weeks you can have your puppy begging to be groomed. We all know how much Welshies love to eat – just refer to the last issue of the STARTER BARKS. With the use of some tasty morsels and very encouraging words, the puppy can learn to love being groomed. This article will explain how to get a puppy accustomed to being groomed, how to groom a pet Welshie, how to handle that fluffy neutered coat and some tips on grooming the show dog from my perspective. These are only my observations of grooming and there are many other innovative ways to groom and present a dog for pet or show. Just as there are different ways to handle dogs in the show ring to look their best, there are different opinions on how to groom a Welshie. I am continually learning and I invite you to share your opinions on grooming. The best presentation of the dog, according to the breed standard, should be foremost in our discussion and not what the fad of the year is. The goal in grooming for all my dogs is for health and cleanliness. Grooming the Puppy Puppies may balk at the idea of being groomed, but if you do a little each day and reward the puppy for its efforts of staying on the grooming table for five minutes, you will be pleased with the results for years to come. -

Grooming 101 for Pet Owners

Grooming 101 for Pet Owners Regular grooming keeps your dog clean, healthy and manageable, as well as preventing yeast infections caused by matted hair, periodontal disease caused by uncared for teeth, ear infections from excessive buildup of wax, dirt and bacteria, etc. This article covers basic at-home grooming and ways to make the process more pleasant for everyone involved. How often should I brush my dog? Initially, you will want to start by brushing your puppy or dog every day to get him/her accustomed to the process. Start small, but do a little bit every day. Do quit because he or she doesn’t like it – or they never will. With repetition, your dog will learn to tolerate the grooming and enjoy the attention. Once your dog is accustomed to being groomed the frequency at which you brush will be determined by the length of your dog’s coat. Dogs with thick coats will need to be brushed 2-3 times per week, while dogs with long hair will likely require daily grooming to avoid tangling and matting. You will be most successful with home grooming, if you elevate your dog off of the floor. Use a table, counter, washer or dryer that has a non-slip bath mat on it. This takes away the dogs leverage and makes them uncomfortable and less likely to struggle, and puts less strain on your back from bending over. What type of brush or comb should I use? Wire Pin Brush – this brush is the best to use on medium to long hair dogs, or those with curly coats. -

Dog Breeds Volume 5

Dog Breeds - Volume 5 A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Russell Terrier 1 1.1 History ................................................. 1 1.1.1 Breed development in England and Australia ........................ 1 1.1.2 The Russell Terrier in the U.S.A. .............................. 2 1.1.3 More ............................................. 2 1.2 References ............................................... 2 1.3 External links ............................................. 3 2 Saarloos wolfdog 4 2.1 History ................................................. 4 2.2 Size and appearance .......................................... 4 2.3 See also ................................................ 4 2.4 References ............................................... 4 2.5 External links ............................................. 4 3 Sabueso Español 5 3.1 History ................................................ 5 3.2 Appearance .............................................. 5 3.3 Use .................................................. 7 3.4 Fictional Spanish Hounds ....................................... 8 3.5 References .............................................. 8 3.6 External links ............................................. 8 4 Saint-Usuge Spaniel 9 4.1 History ................................................. 9 4.2 Description .............................................. 9 4.2.1 Temperament ......................................... 10 4.3 References ............................................... 10 4.4 External links -

Ancol Sizing Guide

Size Guides Choosing the One Size Collars Collar Size 1 Collar Size 2 Collar Size 3 correct dog collar To fit sizes 20-26cm To fit sizes 26-31cm To fit sizes 28-36cm Bichon Frise Dachshund Cairn Terrier Ancol are the only company to offer this Chihuahua (miniature) Dachshund Shih Tzu Jack Russell Poodle (miniature) system of collar sizing to help your staff and Yorkshire Terrier Pekingese Welsh Corgi your customers select and identify the correct collar for their dog. Collar Size 4 Collar Size 5 Collar Size 6 The Ancol system uses the breed of dog as a guideline but To fit sizes 35-43cm To fit sizes 39-48cm To fit sizes 45-54cm also includes a special tape, which converts accurately to Beagle Cocker Spaniel Afghan Hound Cavalier K. Charles Poodle (standard) Border Collie the correct neck size. Collars are sized from 1-9, which Pug Saluki Boxer makes recognition and remembering the size a lot easier. West Highland Springer Spaniel Dalmation The Ancol collars are adjustable in all cases so that a fair Collar Size 7 Collar Size 8 Collar Size 9 degree of flexibility exists between the sizes. The adjustability of the collar means that for every dog To fit sizes 50-59cm To fit sizes 55-63cm To fit sizes 65-74cm there will be at least two collar sizes that will be acceptable Bassett German Shepherd Bloodhound Dobermann Gordon Setter Bull Mastiff and of comfortable fit. Pointer Great Dane St. Bernard Weimaraner Labrador Rottweiler Product labels highlight the size and clearly differentiates the collars from leads when on display. -

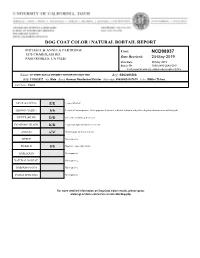

Dog Coat Color / Natural Bobtail Report Ncd98937

DOG COAT COLOR / NATURAL BOBTAIL REPORT MICHAEL & ANGELA PARTRIDGE Case: NCD98937 1575 CHAROLAIS RD. Date Received: 24-May-2019 PASO ROBLES, CA 93446 Print Date: 30-May-2019 Report ID: 7399-2480-2685-5011 Verify report at www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/myvgl/verify.htm Name: CH SHORTALES & CORONET WITH OR WITHOUT YOU Reg: SS02265506 DOB: 11/14/2017 Sex: Male Breed: German Shorthaired Pointer Microchip: 956000010167615 Color: White / Ticked Call Name: Cisco MC1R (E LOCUS) E/E 2 copies of black BROWN (TYRP1) b/b 2 copies of brown present - black pigment (if present) is diluted to brown, red/yellow dogs have brown noses and foot pads DILUTE (MLPH) D/D Full color, no dilute gene present DOMINANT BLACK K/K 2 copies of dominant black are present AGOUTI at/at Homozygous for black-and-tan MERLE Not requested. PIEBALD S/S Dog has 2 copies of piebald. HARLEQUIN Not requested. NATURAL BOBTAIL Not requested. DOBERMAN OCA Not requested. PANDA SPOTTING Not requested. For more detailed information on Dog Coat Color results, please go to: www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/services/coatcolordog.php Dog Coat Color / Fur Type Results with Explanations MC1R - All Variants BROWN (TYRP1) Em/Em - 2 copies of mask - dog has mask B/B - Does not carry brown - cannot have brown offspring. Em/E - 1 copy of mask and 1 copy of black - dog has mask and carries black B/b - 1 copy of brown present - carrier. Em/e - 1 copy of mask and 1 copy of red/yellow - dog has mask and carries b/b - 2 copies of brown present - black pigment (if present) is diluted red/yellow/cream to brown, red/yellow dogs have brown noses and foot pads.