How Should I Act?: Shakespeare and the Theatrical Code of Conduct Ann E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

45477 ACTRA 8/31/06 9:50 AM Page 1

45477 ACTRA 8/31/06 9:50 AM Page 1 Summer 2006 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists ACTION! Production coast to coast 2006 SEE PAGE 7 45477 ACTRA 9/1/06 1:53 PM Page 2 by Richard We are cut from strong cloth Hardacre he message I hear consistently from fellow performers is that renegotiate our Independent Production Agreement (IPA). Tutmost on their minds are real opportunities for work, and We will be drawing on the vigour shown by the members of UBCP proper and respectful remuneration for their performances as skilled as we go into what might be our toughest round of negotiations yet. professionals. I concur with those goals. I share the ambitions and And we will be drawing on the total support of our entire member- values of many working performers. Those goals seem self-evident, ship. I firmly believe that Canadian performers coast-to-coast are cut even simple. But in reality they are challenging, especially leading from the same strong cloth. Our solidarity will give us the strength up to negotiations of the major contracts that we have with the we need, when, following the lead of our brothers and sisters in B.C. associations representing the producers of film and television. we stand up and say “No. Our skill and our work are no less valuable Over the past few months I have been encouraged and inspired than that of anyone else. We will be treated with the respect we by the determination of our members in British Columbia as they deserve.” confronted offensive demands from the big Hollywood companies I can tell you that our team of performers on the negotiating com- during negotiations to renew their Master Agreement. -

March 23 Cd Releases

MARCH 23 CD RELEASES The 13th Floor Elevators The Complete Singles Collection Abscess Dawn of Inhumanity Absolute Ensemble Absolute Zawinul Airscape Now & Then Mose Allison The Way of the World Alter Bridge Live From Amsterdam S.A. Andree There's a Fault Ara Ara Autechre Oversteps Ball Greezy 305 Barren Earth The Curse of the Red River Dame Shirley Bassey Performance Chuck Berry Have Mercy: His Complete Chess Recordings 1969-1974 Big Jeff Bess Tennessee Home Brew Bettie Serveert Pharmacy of Love Justin Bieber My World 2.0 The Bird and the Bee Interpreting the Masters Vol. 1 Bluesmasters Featuring Mickey Thomas - Bluesmasters Featuring Mickey Thomas Joe Bonamassa Black Rock Graham Bonnet The Day I Went Mad Bonobo Black Sands Bright Eyes & Neva Dinova One Jug of Wine, Two Vessels Archie Bronson Outfit Coconut Brotha Lynch Hung Dinner and a Movie Harold Budd & Clive Wright Little Windows Can Unlimited Edition Ben Cantelon Running After You Chanela Flamenco Latino Nat King Cole & His Trio Rare Radio Tranascriptions Ken Colyer's Jazzmen Somewhere Over the Rainbow Ron Contour & Factor Saffron The Courteeners Falcon David Davidson Beautiful Strings Dbridge & Instra-Mental Fabriclive 50 Dead Meadow Three Kings (CD/DVD) Decemberadio Live Paul Dianno The Living dead The Dillinger Escape Plan Option Paralysis Disturbed The Sickness 10th Anniversary Edition DJ Clay Let 'Em Bleed DJ Virtual Vault In Trance We Trust 15 DMX Mixtape Fats Domino Essential Hits & Early Recordings Jimmy Donley The Shape You Left Me In Double Dagger Masks EP The Dreamers – John Zorn IPOS: The Book of Angels VOl. 14 Drink Up Buttercup Born and Thrown on a Hook Dunkelbunt Morgenlandfahrt Jimmy Edwards Love Bug Crawl Jack Elliott At Lansdowne Studios, London F. -

God As a Totalitarian Figure in Milton's Paradise Lost

God as a totalitarian figure in Milton's Paradise Lost Levak, Helena Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:073970 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti - nastavnički smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti - nastavnički smjer Helena Levak Bog kao totalitarni vladar u Miltonovom Izgubljenom raju Diplomski rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Borislav Berić Osijek, 2017 Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti - nastavnički smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti - nastavnički smjer Helena Levak Bog kao totalitarni vladar u Miltonovom Izgubljenom raju Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: teorija i povijest književnosti Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Borislav Berić Osijek, 2017 J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double -

A Zeitgeist Films Release Theatrical Booking Contact: Festival Booking and Publicity Contact

Theatrical Booking Festival Booking and Contact: Publicity Contact: Clemence Taillandier / Zeitgeist Films Nadja Tennstedt / Zeitgeist Films 212-274-1989 x18 212-274-1989 x15 [email protected] [email protected] a zeitgeist films release act of god a film by Jennifer Baichwal Is being hit by lightning a random natural occurrence or a predestined event? Accidents, chance, fate and the elusive quest to make sense out of tragedy underpin director Jennifer Baichwal’s (Manufactured Landscapes) captivating new work, an elegant cinematic meditation on the metaphysical effects of being struck by lightning. To explore these profound questions, Baichwal sought out riveting personal stories from around the world—from a former CIA assassin and a French storm chas- er, to writer Paul Auster and improvisational musician Fred Frith. The philosophical anchor of the film, Auster was caught in a terrifying and deadly storm as a teenager, and it has deeply affected both his life and art: “It opened up a whole realm of speculation that I’ve continued to live with ever since.” In his doctor brother’s laboratory, Frith experiments with his guitar to demonstrate the ubiquity of electricity in our bodies and the universe. Visually dazzling and aurally seductive, Act of God singularly captures the harsh beauty of the skies and the lives of those who have been forever touched by their fury. DIRECTOR’S NOTES I studied philosophy and theology before turning to documentary and, in some ways, the questions I was drawn to then are the ones I still grapple with now, although in a different context. Two of these, which specifically inform this film, are the relationship between meaning and randomness and the classical problem of evil. -

A JOURNEY from THIS WORLD to the NEXT by Henry Fielding

1 A JOURNEY FROM THIS WORLD TO THE NEXT By Henry Fielding INTRODUCTION Whether the ensuing pages were really the dream or vision of some very pious and holy person; or whether they were really written in the other world, and sent back to this, which is the opinion of many (though I think too much inclining to superstition); or lastly, whether, as infinitely the greatest part imagine, they were really the production of some choice inhabitant of New Bethlehem, is not necessary nor easy to determine. It will be abundantly sufficient if I give the reader an account by what means they came into my possession. Mr. Robert Powney, stationer, who dwells opposite to Catherine-street in the Strand, a very honest man and of great gravity of countenance; who, among other excellent stationery commodities, is particularly eminent for his pens, which I am abundantly bound to acknowledge, as I owe to their peculiar goodness that my manuscripts have by any means been legible: this gentleman, I say, furnished me some time since with a bundle of those pens, wrapped up with great care and caution, in a very large sheet of paper full of characters, written as it seemed in a very bad hand. Now, I have a surprising curiosity to read everything which is almost illegible; partly perhaps from the sweet remembrance of the dear Scrawls, Skrawls, or Skrales (for the word is variously spelled), which I have in my youth received from that lovely part of the creation for which I have the tenderest regard; and partly from that temper of mind which makes men set an immense value on old manuscripts so effaced, bustoes so maimed, and pictures so black that no one can tell what to make of them. -

Toy Cars Down Steep Slopes By: Caitlin Turnage

Toy Cars Down Steep Slopes By: Caitlin Turnage CHARACTER NAME BRIEF DESCRIPTION AGE GENDER CATHY Home owner 45 Female JACK Cathy's adventurous son 24 Male RAINY Cathy's diseased son 29 Male AMY Married to Rainy 27 Female SYNOPSIS: Cathy is a mother who has shoved her children out of her house with a tendency to hoard. However, when she's diagnosed with Huntington's disease she understands it's time to change--and time to move, but she can't do it without her estranged sons help. When the boys return, they have to come to terms with their mother's hereditary disease, and their own death sentence. PRODUCTION HISTORY: Staged Reading at the University of Houston Act I SCENE 1 Interior of a manufactured home in Mississippi. The home has been encased in brick to make it a permanent residence. In the main bedroom, shelves line the walls with various knickknacks. The room has a distinct theme of childhood whimsy. The room is somewhere between a collector’s haven and a hoarder’s hovel; it’s organized chaos. On one side of the bed is a piled collection of ceramic dish-ware. In another corner of the room are toy cars, some of them still in their shiny packages stacked high on top of each other. Coloring books and stickers and different objects with toy car or race car themes also litter this mountain. Along the back wall surrounding the bed is a book case lined with journals of all sizes and shapes. The journals on the left hand side are untouched and pristine, while the journals on the right side are worn and battered like someone’s tossed them around. -

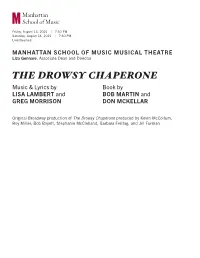

THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR

Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag, and Jill Furman Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag and Jill Furman Evan Pappas, Director Liza Gennaro, Choreographer David Loud, Music Director Dominique Fawn Hill, Costume Designer Nikiya Mathis, Wig, Hair, and Makeup Designer Kelley Shih, Lighting Designer Scott Stauffer, Sound Designer Megan P. G. Kolpin, Props Coordinator Angela F. Kiessel, Production Stage Manager Super Awesome Friends, Video Production Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi, Rebecca Prowler, Jensen Chambers, Johnny Milani The Drowsy Chaperone is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com STREAMING IS PRESENTED BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT WITH MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL (MTI) NEW YORK, NY. All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com WELCOME FROM LIZA GENNARO, ASSOCIATE DEAN AND DIRECTOR OF MSM MUSICAL THEATRE I’m excited to welcome you to The Drowsy Chaperone, MSM Musical Theatre’s fourth virtual musical and our third collaboration with the video production team at Super Awesome Friends—Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi and Rebecca Prowler. -

Open 2-Katherine Oneill Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES ABERRATION KATHERINE O’NEILL SPRING 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Creative Writing with honors in Creative Writing Reviewed and approved* by the following: Thomas Noyes Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing Thesis Supervisor/ Honors Adviser George Looney Professor of English and Creative Writing Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This thesis explores the writing process using a critical preface to analyze the work of the thesis, discuss the creative process, and discuss the author’s approach to the process. The thesis also includes a full length novel to demonstrate the craft and a bibliography that lists inspiration texts along with research. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 ...................................................................................................................... 12 Chapter 3 ...................................................................................................................... 16 Chapter 4 ...................................................................................................................... 20 Chapter 5 ...................................................................................................................... 28 Chapter -

Productions in Ontario 2007

PRODUCTION IN ONTARIO with assistance from Ontario Media Development Corporation 2007 www.omdc.on.ca You belong here FEATURE FILMS - THEATRICAL BLINDNESS EATING BUCCANEERS Company: Rhombus Media (Blindness) Inc. Producers: Mark Montefiore, Jennifer Mesich Producers: Niv Fichman, Sonoko Sakai, Executive Producers: Bill Keenan, ADORATION Andrea Barata Ribeiro Tracy Keenan Company: Ego Film Arts Executive Producers: Gail Egan, Director: Bill Keenan Producers: Atom Egoyan, Simone Urdl, Simon Channing Williams Writer: Bill Keenan Jennifer Weiss Director: Fernando Meirelles Production Manager: Adili Yahel Executive Producers: Robert Lantos, Writer: José Saramago D.O.P.: Wesley Legge Michele Halbertstadt, Laurent Petin Production Manager: Ivan Teixeira Key Cast: Peter Keleghan, Leah Pinsent, Director: Atom Egoyan D.O.P.: Cesar Charlone Neil Crone, Jeff White, Shanon Beckner, Production Designer: Phillip Baker Key Cast: Julianne Moore, Mark Ruffalo, Steven McCarthy D.O.P.: Paul Sarossy Sandra Oh, Don McKellar Shooting Dates: 8/1/2007 - 9/30/2007 Key Cast: Rachel Blanchard, Scott Speedman, Shooting Dates: 7/24/2007 - 10/15/2007 Devon Bostick FLASH OF GENIUS Shooting Dates: 9/17/2007 - 10/19/2007 CRY OF THE OWL Company: Spyglass Entertainment/ Company: Sienna Films Productions XI Inc. Universal Pictures Productions AMERICAN PIE PRESENTS: Producer: Julia Sereny, Jennifer Kawaja Producers: Gary Barber, Roger Birnbaum, BETA HOUSE Executive Producers: Steve Ujlaki, Michael Lieber David Thompson, Jamie Laurenson, Executive Producers: Miles Dale, Company: -

Rumors ~ by Badsquirrel Disclaimers: This Is an Original Work of Fiction

~ Rumors ~ by BadSquirrel Disclaimers: This is an original work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, places or events is a complete and total accident. I only wish I knew these women and the town of Edgewater. In fact, if you know them, e-mail me at once. Content warning: There will be angst, sex, a little rough language and rampant lesbianism. If this is not your cup of tea, don't drink it. If you are not old enough to read this, you will be soon. This will still be here when you are older. If you live in a place where this is not legal...lock the door and have at it. Note: There is Spanish spoken in this story. I do not speak Spanish. Oh sure, I can count to ten if I'm not interrupted and I'm pretty sure I can order eggs, but Lord knows how they'll be served to me. Since I don't speak Spanish and didn't want to ask any of the very straight manly men at my day job to help me out, I used a free on-line translation service. I was so proud of myself. What did I know? It looked like Spanish. So I submitted the story. Turns out my translations bore about the same relation to Spanish as an omelet does to eggs. (I seem to keep bringing up eggs. Maybe I'm ovulating.) Anyway, I bow down to Webwarrior for unscrambling my omelet of Spanish, and Bardeyes for sending me the translations and letting me work them into the story. -

Mack Wilds Afterhours Clean Version Free Download Snoop Dogg's Albums, Ranked

mack wilds afterhours clean version free download Snoop Dogg's albums, ranked. Snoop Dogg first landed on the music world’s radar as Dr. Dre’s preferred collaborator on 1992’s The Chronic , and since then, he has unleashed solo albums and collaborative joints that have taken him to the top of the hip-hop world and always dancing on the fringes of pop music. In honor of his fine new album Bush , which is in stores Tuesday, here’s a deeply scientific ranking of Snoop’s albums, from worst to first. 14. Doggumentary (2011) The title for this album was originally batted around as some variation on Doggystyle 2 , and it’s fortunate that cooler heads prevailed to jettison that name, as Doggumentary has no business associating with Snoop’s finest work. It takes the form of a lot of his latter-day outings, but for some reason the chemistry is all wrong. As I noted in my review of Snoop’s latest album Bush , he’s pretty much the same on every release (which is to say there’s a baseline of quality work at the outset), and it’s up to his collaborators to tease out greater levels of his ineffable Snoopness. Just about everybody strikes out on Doggumentary , even though the list of guests includes Kanye West, Gorillaz, R. Kelly, Wiz Khalifa, Willie Nelson, and peaking-at-the-time T-Pain. Doggumentary is the longest album in Snoop’s catalog, and it feels even longer. 13. Tha Doggfather (1996) In the three years between Snoop’s breakout debut Doggystyle and the follow-up, the dude crammed in an awful lot of living: He became estranged from mentor Dr. -

Analyze This

Analyze This Dir: Harold Ramis, USA, 1999 A review by George Larke, University of Sunderland It's parody time again for the gangster genre. Just in case we were tempted into taking the films too seriously, we are reminded that the cinematic gangster and his surroundings are essentially cliché forms. Analyze This, directed by Harold Ramis and starring Robert De Niro and Billy Crystal, takes the post-classical fashion of masculine angst popular in the gangster film from The Godfather (1972) to Donnie Brasco (1995) and mercilessly laughs at it. Ramis, who previously directed another comedy success, Groundhog Day (1993), wrote the script along with Peter Tolan and Kenneth Lonergan. At first glance, the film invites comparison to another gangster parody, Mad Dog and Glory (1993) wherein De Niro played against type, as the "nobody" schmuck, while Bill Murray played the mobster. That film did not work very well. De Niro cannot play the schmuck opposite a comedy gangster it stretches imagination and parody too far. For Analyze This, switching the roles and replacing Murray with Billy Crystal has produced a more fitting character balance. Mob boss, Paul Vitti (De Niro), is suffering from a severe case of "work-related stress". The biggest meeting of New York crime bosses since the Appalachian gathering of 1957 is imminent. He's just witnessed the assassination of one of his best friends and certain associates are suggesting he was involved in ordering it. The panic attacks are getting worse and it's affecting his work in a set-piece interrogation and assassination scene he cannot pull the trigger, much to his henchman's and, more pointedly, the victim's disgust.