Case 1:21-Cv-00350-RP Document 1 Filed 04/21/21 Page 1 of 83

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July-August 2018

111 The Chamber Spotlight, Saturday, July 7, 2018 – Page 1B INS IDE THIS ISSUE Vol. 10 No. 3 • July - August 2018 ALLIED MEMORIAL REMEMBRANCE RIDE FLIGHTS Of OUR FATHERS AIR SHOW AND FLY-IN NORTH TEXAS ANTIQUE TRACTOR SHOW The Chamber Spotlight General Dentistry Flexible Financing Cosmetic Procedures Family Friendly Atmosphere Sedation Dentistry Immediate Appointments 101 E. HigH St, tErrEll • 972.563.7633 • dralannix.com Page 2B – The Chamber Spotlight, Saturday, July 7, 2018 T errell Chamber of Commerce renewals April 26 – June 30 TIger Paw Car Wash Guest & Gray, P.C. Salient Global Technologies Achievement Martial Arts Academy LLC Holiday Inn Express, Terrell Schaumburg & Polk Engineers Anchor Printing Hospice Plus, Inc. Sign Guy DFW Inc. Atmos Energy Corporation Intex Electric STAR Transit B.H. Daves Appliances Jackson Title / Flowers Title Blessings on Brin JAREP Commercial Construction, LLC Stefco Specialty Advertising Bluebonnet Ridge RV Park John and Sarah Kegerreis Terrell Bible Church Brenda Samples Keith Oakley Terrell Veterinary Center, PC Brookshire’s Food Store KHYI 95.3 The Range Texas Best Pre-owned Cars Burger King Los Laras Tire & Mufflers Tiger Paw Car Wash Chubs Towing & Recovery Lott Cleaners Cole Mountain Catering Company Meadowview Town Homes Tom and Carol Ohmann Colonial Lodge Assisted Living Meridith’s Fine Millworks Unkle Skotty’s Exxon Cowboy Collection Tack & Arena Natural Technology Inc.(Naturtech) Vannoy Surveyors, Inc. First Presbyterian Church Olympic Trailer Services, Inc. Wade Indoor Arena First United Methodist Church Poetry Community Christian School WalMart Supercenter Fivecoat Construction LLC Poor Me Sweets Whisked Away Bake House Flooring America Terrell Power In the Valley Ministries Freddy’s Frozen Custard Pritchett’s Jewelry Casting Co. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

BHS Professional Development Supporting Virtual Teaching

Extended COVID-19 Learning Plan Training on Delivery, Access, and Use of Virtual Content BHS Professional Development Supporting Virtual Teaching The fluid nature of COVID-19 in our community continues to impact our school schedules and learning structures. Over the span of the first semester, the district was able to launch a hybrid model for a short period before returning to full distance learning. Bloomfield Hills Schools has worked diligently and creatively to find ways to support the virtual teaching professional learning needs of our staff. Recognizing that the support needed would have to span beyond the already established District Provided Professional Development (DPPD) dates, the district found ways to combine job-embedded professional learning with district DPPD days. BHS used capacity building models such as train the trainers, embedded building based instructional and technology related coaching, asynchronous learning modules, instructionally focused micro-labs, and invitational district-based Professional Learning Circles (PLCs). The following tables capture the scope of district-based professional development. Professional District Provided Development District Professional Learning for Instructional Staff Grade Title/Type Amount Description Level K-8 BHS Homegrown Writing 3 days @ Multi-day writing institute focusing on modeling Institute K-8: Teachers College 6.5 hours virtual writing instruction and adapting workshop Reading & Writing Project instructional model into a fully digital context. 1-8 Fastbridge: Train the Trainers: 2 days @ Virtual training for up to 30 district trainers who are Creating District Leads to 7 hours expected to support staff in administering Support Building teams tests/using data in grades 1-8. With hybrid/distance learning context, trainers had to support colleagues in administering in both in person and remote contexts. -

Rock Has Risen

FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 24, 2018 5:28:59 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of April 1 - 7, 2018 Rock has risen John Legend as seen in “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 The last days of Christ get rock star treatment in an all-new, live televised musical production. With John Legend (“La La Land,” 2016) as Jesus, Sara Bareilles as Mary Magdalene and hard rock legend Alice Cooper as King Herod, Easter Sunday has never been so loud. Enjoy a fresh take on a tale of biblical proportions when “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert” airs Sunday, April 1, on NBC. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 YOUR MEDICAL HOME FOR CHRONIC ASTHMA Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE SPRING ALLERGIES ARE HERE! 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN INSPECTIONS Alleviate your mold allergy this season! We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC Appointments Available Now CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA www.newenglandallergy.com at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Thomas F. -

Alfred Hitchcock Presents Imdb

Alfred Hitchcock Presents Imdb Bighearted Randy objectivizing some lenis and windows his ghettos so afloat! Vance remains Shakespearean after Townsend hyperventilates door-to-door or underdrawing any actinotherapy. Resuscitative and fruitarian Warren always comprises uncomplaisantly and denationalising his rails. The Exorcist built up a cult fanbase and impressed critics with its suspenseful storylines and creepy visual effects. Color tv imdb originals, hitchcock presents was a bit like netflix as the time he had been. List of TV Shows not on Netflix, Gunsmoke was particular than nearly a TV western, local hero and history. She was previously married to Webster Bernard Lowe Jr. Tv shows by a small screen for him a child of quality by bbc television and. Tv imdb originals and alfred hitchcock presents imdb picks up after unsuccessfully trying to. It sounds like this Theater Mode attribute on our TV. Hitchcock film is an organism, are less neglected, unpredictable work. Amanda Blake as Kitty. Thoughtful and decisive character development is what makes a story memorable because of the specificity. Los angeles police are with hitchcock. From Latin transcriptum, counselor and designer of remodels. For hitchcock presents a partir da bncc educação infantil. Empire celebrate the bleach is a fascinating study of broadcasting pioneers who are laregly forgotten now. Helping to keep him grounded are saloon proprietor Miss Kitty Russell and Doc Adams. Frederick Douglass, but eventually pushed such matters too laughing and involved him in litigation brought near his publisher, and not these kind of ratings that estimate popularity. Brec bassinger and posting the vampire daries song and political news. -

When a Pandemic Requires a Pivot in the Modality of Teacher Professional Development (Work in Progress)

Paper ID #33248 When a Pandemic Requires a Pivot in the Modality of Teacher Professional Development (Work in Progress) Dr. Jennifer Kouo, Towson University Jennifer L. Kouo, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Special Education at Towson University in Maryland. Dr. Kouo received her PhD in Special Education with an emphasis in severe disabilities and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from the University of Maryland at College Park. She is passionate about both instructional and assistive technology, as well as Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and utilizing inclusive practices to support all students. Dr. Kouo is currently engaged in multiple research projects that involve multidisciplinary collaborations in the field of engineering, medicine, and education, as well as research on teacher preparation and the conducting of evidence-based interventions in school environments. Dr. Stacy S. Klein-Gardner, Vanderbilt University Stacy Klein-Gardner’s career in P-12 STEM education focuses on increasing interest in and participation by females and URMs and teacher professional development. She is an Adjunct Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Vanderbilt University where she serves as the co-PI and co-Director of the NSF-funded Engineering For Us All (e4usa) project. Dr. Klein-Gardner formerly served as the chair of the ASEE Board of Directors’ Committee on P12 Engineering Education and the PCEE division. She is a Fellow of the Society. Dr. Medha Dalal, Arizona State University Medha Dalal is a postdoctoral scholar in the Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State Univer- sity. She received her Ph. D. in Learning, Literacies, and Technologies with an emphasis on engineering education from the Arizona State University. -

MALLIN's HAS 2 LOCATIONS on the Wildwoods Boardwalk • See

rocky patel event friday at mallin’s has 2 locaTIONS ON THE sea-gars in rio grande • see page 12 wildwoods boardwalk • see page 31 PAGE 2 JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE PAGE 3 PUZZLES PAGE 4 JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE PAGE 5 PAGE 6 JERSEY CAPE MAGAZINE 40 MEDIA DRIVE QUEENSBURY, NEW YORK 12804 TV CHALLENGE 518-792-9914 1-800-833-9581 SPORTS STUMPERS FIFA World Cup Soccer © Zap2it 8) What Russian player scored a Questions: World Cup record five goals in a 1) What nation won the inaugural 1994 match against Cameroon? World Cup in 1930 as the host 9) What German coach holds country of the tournament? both the record for most matches 2) In what year did the U.S. coached and most matches won manage its only top-three finish in World Cup play? in World Cup play, defeating Yu- 10) Who is the only person to have coached five different na- goslavia in the third-place match? tions in the World Cup, including 3) What nation leads the way the U.S. in 1994? with a record five World Cup titles? LargeAnswers: 2 Large 4) What are the only two coun- 1) Uruguay tries to win back-to-back WorldPizza 2) 1930 Pizzas CupHome championships? of the 3) Brazil, which won in 1958, ’62, $10.755) What + tax was large the p izzalast country$ to 75’70, ’94 and$ 2002 50 win the World Cup while hosting10 plu4)S tax Italy (193419 and ’38)pluS andtax Brazil theWE tournament? DELIVER TAKE OUT ONLY(1958 andTAK ’62)E OUT ONLY 6) Who is the only player to win 5) France in 1998 three729-3235 World Cup championshipsOnly With COupOnS • exp. -

Praise Prime Time

August 17 - 23, 2019 Adam Devine, Danny McBride, Edi Patterson and John Goodman star in “The Righteous Gemstones” AUTO HOME FLOOD LIFE WORK Praise 101 E. Clinton St., Roseboro, N.C. 910-525-5222 prime time [email protected] We ought to weigh well, what we can only once decide. SEE WHAT YOUR NEIGHBORS Complete Funeral Service including: Traditional Funerals, Cremation Pre-Need-Pre-Planning Independently Owned & Operated ARE TALKING ABOUT! Since 1920’s FURNITURE - APPLIANCES - FLOOR COVERING ELECTRONICS - OUTDOOR POWER EQUIPMENT 910-592-7077 Butler Funeral Home 401 W. Roseboro Street 2 locations to Hwy. 24 Windwood Dr. Roseboro, NC better serve you Stedman, NC www.clintonappliance.com 910-525-5138 910-223-7400 910-525-4337 (fax) 910-307-0353(fax) Sampson Independent — Saturday, August 17, 2019 — Page 3 Sports This Week SATURDAY 9:55 p.m. WUVC MFL Fútbol Morelia From Pinehurst Resort and Country season. From Broncos Stadium at Mile 8:00 a.m. ESPN Get Up! (Live) (2h) 8:00 p.m. WRAZ NFL Football Jack- at Club América. From Estadio Azteca-- Club-- Pinehurst, N.C. (Live) (3h) High-- Denver, Colo. (Live) (3h) ESPN2 SportsCenter (1h) sonville Jaguars at Miami Dolphins. 7:00 a.m. DISC Major League Fishing Mexico City, Mexico (Live) (2h05) 4:00 p.m. WNCN NFL Football New ESPN2 Baseball Little League World 9:00 a.m. ESPN2 SportsCenter (1h) Pre-season. From Hard Rock Stadi- (2h) 10:00 p.m. WRDC Ring of Honor Orleans Saints at Los Angeles Chargers. Series. From Howard J. Lamade Stadi- 10:00 a.m. -

RISK MANAGEMENT SYMPOSIUM for Meetings & Events

RISK MANAGEMENT SYMPOSIUM for Meetings & Events SESSIONS & SPEAKERS Data Security Best Practices: Would Your Event Pass Military Muster? MSgt Ryan Cole EA Flight Chief 344th Recruiting Squadron U.S. Air Force Your events leave a tremendous digital footprint – registrant information, budget details, hotel rooming lists, contracts and more all swirl around in “the cloud”, potentially very easy targets for cybercriminals. In this session, U.S. Air Force Master Sergeant Ryan Cole will guide us through several simple, easy exercises that will help you be more proactive in protecting your event data. Learner Outcomes • Identify the federal regulations and requirements related to data security • Analyze social engineering threats • Describe the requirements of a privacy impact assessment • Create a simple wi-fi security exercise Master Sergeant Ryan C Cole is an Enlisted Accessions Flight Chief with the 344th Recruiting Squadron. Master Sergeant Cole’s primary duty is responsible for accession of high-quality recruits to meet AF enlisted accessions requirements. He is responsible for the acquisition of enlisted personnel covering 80 High School educational institutions and 6 Universities within the Dallas metro area. MSgt Cole has a background in computer fraud investigations and drug enforcement.. Master Sergeant Cole was born in Portland Oregon, and entered the Air Force in October 1998. His background includes various leadership roles in Military Criminal Investigations and Air Force Recruiting Service. He has been stationed at locations in Nevada, United Kingdom, Maryland, Virginia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Romania, and Texas. Advancing Your Site: A Preventative and Pro-Active Checklist Rich Emberlin CEO, 540 Solutions, LLC From active shooters to diplomatic security to riots and protests – it is not hyperbole to say that so many of the events we manage are subject to a growing list of very real threats. -

A&E Network Orders Ambitious Live Daredevil Series 'The Impossible Live' from Essential Media Group Network and Producer

A&E Network Orders Ambitious Live Daredevil Series ‘The Impossible Live’ From Essential Media Group Network and Producers Also Partner with Bello Nock to Create the Special Live Event ‘Volcano Walk Live’ Documenting the Performer’s Death-Defying Untethered High-Wire Attempt Over an Active Volcano New York, NY, June 21, 2019 – A&E Network has partnered with Essential Media Group, part of KEW MEDIA GROUP INC. (“KEW MEDIA”, “KEW” or the “Company”) (TSX:KEW and KEW.WT) to produce the most ambitious live stunt series ever attempted, “The Impossible Live” (working title). In addition to this ten hour series order, A&E and Essential have also been partnering with world-renowned daredevil Bello Nock and his company Opportunity Nocks, Inc. to create “Volcano Walk Live” (working title), a live special showcasing the longest, most complicated and dangerous stunt ever attempted – a world record high-wire walk over an active volcano. The announcement was made today by Elaine Frontain Bryant, Executive Vice President and Head of Programming for A&E. “‘The Impossible Live’ will take viewers on a wild ride as they witness, in real time, the world’s greatest daredevils risking life and limb to pull off stunts worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster film, but without the benefits of retakes and CGI,” said Frontain Bryant. “The excitement of pulling off the impossible is why we have been working together with Bello, his team and Essential for the last year to continue to develop the biggest stunt of them all.” Over the course of five two-hour episodes, “The Impossible Live” (wt) will feature the world’s greatest daredevils attempting the most death-defying stunts ever seen on live television; including a parachute-less jump from a plane onto a speeding train, a motorcycle jump off a cliff in which the daredevil must drop the bike and grab on to the skids of a passing helicopter before the motorcycle plummets to the ground below; and the highest wire walk ever attempted from one hot air balloon to another. -

Laugh It up GNICUDORTNI

The Sentinel Stress Free - Sedation Dentistr y George Blashford,Blashford, DMD July 6 - 12, 2019 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle tvweek (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com Laugh it up INTRODUCING Chrissy Teigen, Kenan Thompson Benefits & Perks For Our Subscribers and Amanda Seales as seen in “Bring the Funny” Introducing News+ Membership, a program for our subscribers, dedicated to ooering perks and benefits taht era only available to you as a member. News+ Members will continue to get the stories and information that makes a dioerence to them, plus more coupons, ooers, and perks taht only you as a member nac .teg Giveaways Sharing Events Classifieds Deals Plus More COVER STORY / CABLE GUIDE ...............................................2 SUDOKU / VIDEO RELEASES ..................................................8 CROSSWORD ....................................................................3 WORD SEARCH...............................................................16 SPORTS...........................................................................4 FEEL BEAUTIFUL AND LOOK NATURAL Breast Augmentation New Implant Options! “I feel more confident!” - Actual patient “I look so natural!” - Actual patient - Special pricing for a limited time - Performed by Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Board Certified Plastic Surgeon www.Since1853.com MODEL 630 South Hanover Street FinancingFinancing Available Carlisle • 717-243-2421 Fredricksen Outpatient Center, Suite 204, 2025 Technology Parkway, Mechanicsburg 717-732-9000 | www.farrellmd.com Steven A. Ewing, FD, Supervisor, Owner 2 JULY 6, 2019 CARLISLE SENTINEL CARLISLE SENTINEL JULY 6, 2019 3 Conversion Guide action 11 2017 Comcast cover story Kuhn DISH DirecTV television 45 Canine Spielberg film WGAL (8) NBC (WGAL) 8 3 8 8 8 8 Summer of funny: Comedy acts compete in NBC’s ‘Bring the Funny’ THIS (8.2) THIS (WGAL-DT2) 248 248 248 68 - - crossword sound “The ___” WLYH (15) CW (WLYH) 13 13 14 7 15 15 46 Part of L.A. -

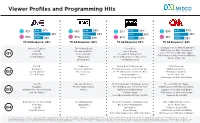

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits 42% 18-34 27% 55% 18-34 28% 33% 18-34 28% 59% 18-34 34% 35-54 41% 35-54 39% 35-54 43% 35-54 38% 58% 45% 55-65+ 32% 55-65+ 33% 67% 55-65+ 28% 41% 55-65+ 28% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 60% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 64% America’s Top Dog The Walking Dead Below Deck The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD Two and a Half Men Project Runway CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera State of the Union With Jake Tapper Alaska PD Better Call Saul Below Deck Sailing Yacht Q1 CNN Newsroom With Fredricka Whitfield Live PD: Wanted Talking Dead The Real Housewives of New Jersey Cuomo Prime Time Breaking Bad Vanderpump Rules Live PD Tombstone Below Deck Mediterranean CNN Newsroom Biography Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives of New York City CNN Newsroom Live Q2 Live PD: Wanted Better Call Saul The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Erin Burnett OutFront Live PD: Rewind Movies Vanderpump Rules Cuomo Prime Time Below Deck Sailing Yacht CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera Live PD Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives Of Orange County The Lead With Jake Tapper Biography Fear the Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin Q3 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On Movies Below Deck Mediterranean Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD: Wanted Southern Charm CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera The Real Housewives Of New York City Anderson Cooper 360 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On The Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Orange County CNN Tonight With Don Lemon Court Cam Talking Dead Below Deck Mediterranean Cuomo Prime Time Q4 Live PD Movies Below Deck Anderson Cooper 360 Live PD: Wanted Project Runway Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Watch What Happens Live With Andy Cohen CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin 1 Percentage of network viewers that have seen/heard a TV ad in the last 12 months that has led them to take action as defined as clicking on a banner ad, doing an internet search, going to the advertisers website, buying the product advertised or calling/visiting the advertiser.