Report Business Tenancies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lex 100 P014-024 Winners.Qxp 17/08/2007 15:08 Page 14

Lex 100 p014-024 Winners.qxp 17/08/2007 15:08 Page 14 Job satisfaction How would you rate your overall job satisfaction? Lex 100 winners 1 Farrer & Co 9.10 2 Harbottle & Lewis LLP 9.00 Analysis = McDermott Will & Emery UK LLP 9.00 This important category is topped this year by Farrer & Co in what’s = Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom (UK) LLP 9.00 been a highly impressive overall performance – the firm appears in every single one of our Lex 100 5 Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP 8.75 Winners tables, often near the top, the first firm to do so. So why is this 6 Covington & Burling LLP 8.71 mid-sized London firm so popular with trainees? It certainly sounds a fun place 7 Latham & Watkins 8.67 to work and offers six seats in a wide variety of practice areas. There’s a strong 8 Ashfords 8.63 bond between current trainees, who praise the ‘great people and great mix of work’, ‘unique atmosphere’ and ‘sheer breadth of training = Stephens & Scown 8.63 opportunities’. Media boutique Harbottle & Lewis comes next. Trainees here feel they have ‘considerably 10 Bristows 8.60 better quality work than peers, better experience and more exposure’. Then, as last year, there’s a strong showing = Shoosmiths 8.60 by five US firms: McDermott Will & Emery, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, Cleary Gottlieb, Covington & 12 Browne Jacobson LLP 8.58 Burling and Latham & Watkins. These firms have not been offering training contracts for that long in London and all have 13 Birketts 8.50 limited intakes. -

Roisin Higgins QC

Advocates Library, Parliament House, Edinburgh, EH1 1RF Telephone: 0131 226 2881 Facsimile : 0131 225 3642 DX ED 549302, Edinburgh 36, LP3 Edinburgh 10 Roisin Higgins QC Year of Call: 2000 Year of Silk: 2015 [email protected] 07739 639083 Professional Career to date Devil Masters: Ian Duguid QC, W James Wolffe QC. 2015: Year of silk 2000: Year of call September 1997 - September 1999:Solicitor, McGrigors (Edinburgh office), Commercial Litigation Department September 1995 - September 1997:Trainee Solicitor, Maclay Murray & Spens (Edinburgh and London offices). Training included experience in commercial litigation, commercial property, venture capital, and mergers and acquisitions. Education & Professional Qualifications Lord Reid Scholarship: (1999-2000) LLB (Hons), Dip LP, University of Glasgow (1990-1995) Areas of Expertise Commercial Contracts Commercial Property Construction and Engineering Intellectual Property Rights Media Law Professional Experience Roisin practised as a solicitor for two years before calling to the Bar in 2000. Since then, she has pursued a practice in commercial litigation and has developed a particular specialism in intellectual property law. In that sphere, she has significant experience in: (i) pharmaceutical and medical patent disputes; (ii) oil and gas patent disputes; (iii) parallel importation of trade marked goods; (iv) trade mark protection for large businesses; (v) protection of copyright and design rights; (vi) broadcasting rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988; and (vi) providing advice to football clubs and cricket and rugby associations in relation to trade mark rights, image rights and rights in footage of sporting events. She is a door tenant at 8 New Square, Lincoln's Inn. Recent Cases East Dunbartonshire Council v Bett Homes Ltd. -

Trainee Handbook

THE QUEEN‟S UNIVERSITY OF BELFAST INSTITUTE OF PROFESSIONAL LEGAL STUDIES Trainee Handbook What you need to know about the day-to-day life of the Institute Please note that this Handbook should be read in conjunction with the „on-line‟ information regarding the course. Appendices 1 Regulations for the Postgraduate Diploma in Professional Legal Studies. 2 On-line Legal Resources available to Institute trainees. 3 University Student Anti-Bullying and Harassment Policy. 4 IPLS Procedure for Maintenance and Enhancement of Standards and Quality. 5 Fire Safety. 6 (a) Bar Programme Specification (b) Solicitor Programme Specification 2011-2012 Edition 2 Introduction Dear trainee, On behalf of all our staff may I welcome you to the Institute of Professional Legal Studies. We are delighted to have you join us here and we hope that you will gain much from your time at the Institute. We are all committed to providing you with the very best in vocational legal training. This handbook is intended to help you maximise your time at the Institute by providing easy access to most of the information which you will need about our policies and procedures. Along with the handbook you will find a certificate stating that you have read the handbook and that you will abide by our policies. You will be expected to sign this certificate when you enrol. Throughout your time at the Institute it will be assumed that you know the contents of the handbook and you may find that you encounter considerable difficulties if you do not. We look forward to working with you. -

Evaluation of the First Year of PRIME

Evaluation of the first year of PRIME November 2012 Authors: Kelly Kettlewell, Clare Southcott, Gill Featherstone, Eleanor Stevens and Caroline Sharp, National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER). For all media enquiries please contact: Guy Nicholls, Allen & Overy. Telephone: 020 3088 4176 Email [email protected] Published in November 2012 by the National Foundation for Educational Research, The Mere, Upton Park, Slough, Berkshire SL1 2DQ www.nfer.ac.uk © National Foundation for Educational Research 2012 Registered Charity No. 313392 ISBN 978-1-908666-36-9 How to cite this publication: Kettlewell, K., Southcott, C., Featherstone, G., Stevens, E. and Sharp, C. (2012). Evaluation of the First Year of PRIME. Slough: NFER. Contents Executive summary i Key findings from the first year of PRIME i Conclusion ii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 What is PRIME? 2 1.2 Who is eligible for a placement through PRIME? 2 2. What proportion of students met the PRIME criteria? 4 3. Recruitment and engagement 5 3.1 Who were the students on PRIME placements? 5 3.2 Awareness and access to the legal profession 6 3.3 How did firms, brokers and schools begin working together on PRIME? 7 3.4 How did representatives use the PRIME criteria to select students? 8 4. PRIME placements: content and satisfaction 10 4.1 How satisfied were students with PRIME? 10 4.2 How did firms structure their placements? 12 4.3 What activities did firms offer students? 12 4.4 How were schools involved in PRIME placements? 14 5. Impact on students 16 5.1 What impact have the placements had on students’ skills development? 16 5.2 What impact have the placements had on students’ knowledge and understanding? 18 5.3 What impact did the placements have on students’ future plans? 19 6. -

Europe - the Next Legal IT Frontier

The leader in legal technology news Issue 159 Europe - the next legal IT frontier Some UK legal IT suppliers are talking about breaking into the United States. Others are taking a crack at the Asia-Pacific market but if last week’s Lex Connect Europe event in Amsterdam was anything to go by, Continental Europe is the most promising marketplace of all. This view is echoed by Derk Kropholler, the vice president of sales at Solution 6 Europe, who predicts that the greatest growth in legal IT sales over the next couple of years will be in Continental Europe. Three factors are currently driving the European market. The first is the pending expansion of the EU, with law firms from the new accession states wanting to gear up so they can compete on an international basis. The second factor is a European-wide drift Buying trends - inertia away from local legacy systems vendors, to the big international rules OK ! suppliers - such as Elite and Solution 6 - who are perceived as the only ones who can provide the latest technologies. The Insider has completed its latest informal The third factor is the growing number of mid-sized European survey of legal IT buying trends. This commercial practices who believe they can carve a niche because confirms that the UK market is enjoying one the large UK and US-based multinational firms, who dominate of its busiest periods since the late 1990s but the top end of the market, do not really understand the region or there were some anomalous findings... the legal culture and are failing to provide the services European For example, our research found that businesses want. -

Report on Review of Contract Law: Formation, Interpretation, Remedies for Breach, and Penalty Clauses

(SCOT LAW COM No 252) Report on Review of Contract Law: Formation, Interpretation, Remedies for Breach, and Penalty Clauses report Report on Review of Contract Law: Formation, Interpretation, Remedies for Breach, and Penalty Clauses Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers under section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 March 2018 SCOT LAW COM No 252 SG/2018/34 The Scottish Law Commission was set up by section 2 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 (as amended) for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law of Scotland. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Lord Pentland, Chairman Caroline S Drummond David E L Johnston QC Professor Hector L MacQueen Dr Andrew J M Steven. The Chief Executive of the Commission is Malcolm McMillan. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. Tel: 0131 668 2131 Email: [email protected] Or via our website at https://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/contact-us/ NOTES 1. Please note that all hyperlinks in this document were checked for accuracy at the time of final draft. 2. If you have any difficulty in reading this document, please contact us and we will do our best to assist. You may wish to note that the pdf version of this document available on our website has been tagged for accessibility. 3. © Crown copyright 2018 You may re-use this publication (excluding logos and any photographs) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3; or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU; or email [email protected]. -

Short Report Template Release

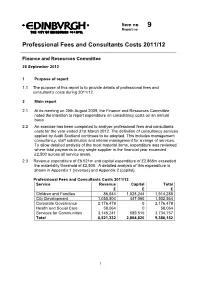

Item no Report no Professional Fees and Consultants Costs 2011/12 Finance and Resources Committee 25 September 2012 1 Purpose of report 1.1 The purpose of this report is to provide details of professional fees and consultant’s costs during 2011/12. 2 Main report 2.1 At its meeting on 25th August 2009, the Finance and Resources Committee noted the intention to report expenditure on consultancy costs on an annual basis. 2.2 An exercise has been completed to analyse professional fees and consultants costs for the year ended 31st March 2012. The definition of consultancy services applied by Audit Scotland continues to be adopted. This includes management consultancy, staff substitution and interim management for a range of services. To allow detailed analysis of the most material items, expenditure was reviewed where total payments to any single supplier in the financial year exceeded £2,500 across all service areas. 2.3 Revenue expenditure of £6.521m and capital expenditure of £2.865m exceeded the materiality threshold of £2,500. A detailed analysis of this expenditure is shown in Appendix 1 (revenue) and Appendix 2 (capital). Professional Fees and Consultants Costs 2011/12 Service Revenue Capital Total ££ £ Children and Families 86,044 1,828,244 1,914,288 City Development 1,055,504 447,060 1,502,564 Corporate Governance 2,176,479 0 2,176,479 Health and Social Care 58,064 0 58,064 Services for Communities 3,145,241 589,516 3,734,757 Total 6,521,332 2,864,820 9,386,152 1 2.4 Expenditure in 2010/11 was as follows: Professional Fees and Consultants Costs 2010/11 Service Revenue Capital Total ££ £ Children and Families 81,560 776,693 858,253 City Development 990,117 114,355 1,104,472 Corporate Governance 1,304,925 16,760 1,321,685 (formerly Corporate Services) Corporate Governance 315,785 0 315,785 (formerly Finance) Health and Social Care 135,902 0 135,902 Services for Communities 753,215 113,758 866,973 Total 3,581,504 1,021,566 4,603,070 2.5 Expenditure in 2009/10 totalled £5.8m, with revenue costs of £4.6m and capital costs of £1.2m being incurred. -

Nflow Identify Demand for DDS

The Orange Rag www.legaltechnology.com September’s big deals DLA pick Eclipse as market leader DLA Piper is to roll out an Eclipse Proclaim case management system to 150 users to handle defendant personal injury work. DLA’s CIO Daniel Pollick said “Proclaim stood out to us as a market leading offering, being best fit for ease of nFlow identify demand use, process management and integration with our strategic partners and case for DDS 2.0 referrers. The fact Eclipse is based in West On the strength of their current round-Britain roadshow, Yorkshire is an added bonus for us.” DDS vendor nFlow say they have been pleasantly surprised by the ‘overwhelmingly positive’ reception their Busy summer and big sites for AlphaLaw Version 5.0 second generation digital dictation system has AlphaLaw has reported a busy summer received. The primary aim of the roadshow was to show with wins at Cripps Harries Hall and the new v5.0, Microsoft .NET based system – which is Thring Townsend Lee & Pembertons for its currently being beta tested by a number of larger UK firms, Claim IT software. Other wins include including Burges Salmon – to existing nFlow customers. Freemans and Tanner & Taylor with its However nFlow sales & marketing director Rob Lancashire Vantage PMS, plus London firms Archers told the Insider the sessions had also helped initiate and Hafiz & Haque, as well as the London discussions “with a number of firms currently using office of Italian lawyers Studio Legal competing solutions, who are considering migrating to Lombardo with its Esprit software. nFlow v5.0. -

Financial Results 2016-2017: Change Gathers Pace Ashurst Tells Microsoft

aka ‘The Orange Rag’ Top stories in this issue… Enable partners with iManage as uncertainty hangs over Tikit TMS integration p2 Tech education in law – a call to arms p4 State of the Industry 2017: Financial Results p8 iManage ConnectLive: p16 Luminance’s CEO talks growth and international strategy p20 ‘Not Petya’: security investments are go p26 Pinsent Masons alternative legal services businesses Financial Results now contribute “well into the seven figures” as it expands its flexible legal resource business Vario into areas 2016-2017: Change including data protection. Mischon de Reya has over the past year developed its gathers pace own data extraction and visualisation tools within the real estate department and is doing significantly more work Revenue generated by alternative legal services may still with Contract Express to automate contracts, with plans to be a drop in the ocean for big City law firms but in 2016- share that data with clients for a fee. 17, that revenue notably became material for many firms, The innovative firm is about to launch its own brand with many having launched home-grown tech tools. management business and over the past year has launched In our report on page 8 we speak about the latest Mishcon Cyber Intelligence to gain an advantage in set of financial results to senior management at law firms litigation, as well as startup venture MDR LAB. including Clifford Chance, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Herbert Smith Freehills, Pinsent Masons, Macfarlanes and FINANCIAL RESULTS 2016-2017 CONTINUES ON P.2 Mishcon de Reya, all of which say are winning business as a result of new delivery models. -

Accounting Standards Committee 10

The Quoted Companies Alliance Annual Review 2008/09 The QCA works for small and mid- cap quoted companies in the UK and Europe to promote and maintain vibrant, healthy and liquid capital markets. 6 Kinghorn Street London EC1A 7HW Tel: 020 7600 3745 Fax: 020 7600 8288 [email protected] www.quotedcompaniesalliance.co.uk 1 Index QCA Officers and Advisors 3 About the Quoted Companies Alliance 4 Chairman’s Statement 5-6 Chief Executive’s Report 7-8 Treasurer’s Statement 9 Reports of the sub-committee chairmen: Accounting Standards Committee 10 Corporate Governance Committee 11 Legal Committee 12 Marketing and Recruitment Committee 13 Markets and Regulations Committee 14 NOMAD Committee 15 Share Schemes Committee 16 Tax Committee 17 Committee Members and Their Work 18-21 QCA Members 22-23 2 QCA Officers and Advisors President The Rt Hon Lord Strathclyde P.C. Chairman Donald Stewart, Faegre & Benson LLP Treasurer Fiona Kelsey, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP John Pierce (until 28 August 2009) Chief Executive Tim Ward (from 1 September 2009) Executive Committee (as of 30 June 2009) Andy Brough, Schroder Investment Management Ltd Paul Lee, Hermes Nigel Burton, Advanced Power AG Mark McBride, Utek Corporation Paul Clarke, Brookwell Limited (Deputy Chairman) Ash Mehta, Orchard Growth Partners Limited Rob Collins, Evolution Securities Katie Morris, Brewin Dolphin Securities Limited Jonathan Eardley, Share Resources Elaine New, Seven Arts Pictures plc Michael Higgins, KPMG Julian Palfreyman, Winterflood Securities Bob Holt, Mears Group -

Cec00591753 0001

From: Wyper, Heather [[email protected]] Sent: 23 March 201 O 16:53 To: Steven Bell Cc: Nolan, Brandon Subject: Report on certain contractual issues: privileged and confidential - prepared in contemplation of litigation Attachments: 1166_001.pdf; report on certain contractual issues.DOC SENT ON BEHALF OF BRANDON NOLAN Dear Steven I attach a copy of my letter and the report referred to therein. Three copies of the report will be delivered to tie tomorrow. Kind regards Brandon Brandon Nolan Partner for McGrigors LLP DDI Fax Mob .. '......c ··' -e ': ,•r ·;·.'. ..•r :g.· a. ·. ·.·r .·-'<,-. ~!}: , . i , · ·.·, ,.· ·· , · . • ·.- M. ' . ...,. ..-.- . .,._. ·. .. -. .-~ . -.- .· •'· •'• .·.- ·- .,,,•, ·. .... ·. ;, . -:- . -;, ... .··, ·... ·. -·. ....·...·. ··· ... ..........-.·. ···.. ·..··.. .... ... ...····. -·. .-·..,... .. ··-··...····- .··..-· .·· .·····-..·· .· ....····,·..··-..····.· .....·.·.·· -. ....-... ·. ..., _, . .,. ·. ·..- .. .. .. ...... , s,. ... ..... ... ..... ·• · .· , • .. .., • •.• .• • • •' · ,.',','•'•' -... ··· ··•·· ,•.·.•.· .. , •,• .•,·.· ','. .",'. ,· ·.-. •.· ' .'.' •, · ··.· -. ,. ,_-, ',' ·. ·' •., .. .•,•.· ··,• -· •....· .·...-·..- •,,•,•., •,• ·.• .•,•,• ..·.·, ",•, ....•.· .·.•,"' ......, ' , \' •.·,· ·.· ",•,•.· ',\, ..._.,..,.... ..· -·· ·.·· .·,· .·.·.....-....·.·.. ·.-.. •,- ..... ,.. ·.-·• . · . ·.- ' ·. -·... ....., .-..·._ .. ·. •.-. ·.•,·.·.·- · '· . _... '· ... ·. · ·. .: : . ' :. · ·. :·" -- ,:, :·, :-- .. ·--:-:. : ; W..W..YY..,f.D,Q9f.!9Q_[_~,_QQf.D ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• -

Finance Committee

McGrigors LLP Finance Committee Inquiry into methods of funding capital investment projects Submission from McGrigors LLP Introduction and Firm Profile McGrigors is a national commercial law firm with offices in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, London, Manchester and Belfast. We employ 458 people in our Scottish office as part of a total staff of 685 people, including 79 partners and over 300 lawyers across the UK. McGrigors advises clients, including national and multi-national organisations, in the public and private sectors on a wide range of commercial issues. Our Energy and Infrastructure and Project Finance teams have now advised on over 160 PPP projects which have reached financial close, having been involved in this process since the introduction of the private finance initiative. In the calendar year 2007 alone, we closed 14 PPP projects with a capital value of £1.5 billion, ranging from roads projects in Austria and Northern Ireland to hospital and schools projects throughout the United Kingdom. At present, we are advising on 20 projects in various stages of procurement with seven at the preferred bidder stage. Non Profit Distributing Structures One facet of our experience which is of particular relevance to the parliamentary enquiry into the funding of capital investment projects is our experience of advising throughout the United Kingdom on non-profit distributing infrastructure financings. The key aspect of the non-profit distributing structures ("NPDs") that have been used in Scottish PPP projects to date is that sponsors' returns over a specified threshold are passed back to the public sector by means of a charitable structure set up at the start of the project.