Atari Games V. Nintendo: Does a Closed System Violate the Antitrust Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Video Game Consoles Introduction the First Generation

A History of Video Game Consoles By Terry Amick – Gerald Long – James Schell – Gregory Shehan Introduction Today video games are a multibillion dollar industry. They are in practically all American households. They are a major driving force in electronic innovation and development. Though, you would hardly guess this from their modest beginning. The first video games were played on mainframe computers in the 1950s through the 1960s (Winter, n.d.). Arcade games would be the first glimpse for the general public of video games. Magnavox would produce the first home video game console featuring the popular arcade game Pong for the 1972 Christmas Season, released as Tele-Games Pong (Ellis, n.d.). The First Generation Magnavox Odyssey Rushed into production the original game did not even have a microprocessor. Games were selected by using toggle switches. At first sales were poor because people mistakenly believed you needed a Magnavox TV to play the game (GameSpy, n.d., para. 11). By 1975 annual sales had reached 300,000 units (Gamester81, 2012). Other manufacturers copied Pong and began producing their own game consoles, which promptly got them sued for copyright infringement (Barton, & Loguidice, n.d.). The Second Generation Atari 2600 Atari released the 2600 in 1977. Although not the first, the Atari 2600 popularized the use of a microprocessor and game cartridges in video game consoles. The original device had an 8-bit 1.19MHz 6507 microprocessor (“The Atari”, n.d.), two joy sticks, a paddle controller, and two game cartridges. Combat and Pac Man were included with the console. In 2007 the Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame (“National Toy”, n.d.). -

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Patents and Monopolization: the Role of Patents Under Section Two of the Sherman Act Ramon A

Marquette Law Review Volume 68 Article 2 Issue 4 Summer 1985 Patents and Monopolization: The Role of Patents Under Section Two of the Sherman Act Ramon A. Klitzke Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Ramon A. Klitzke, Patents and Monopolization: The Role of Patents Under Section Two of the Sherman Act, 68 Marq. L. Rev. 557 (1985). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol68/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PATENTS AND MONOPOLIZATION: THE ROLE OF PATENTS UNDER SECTION TWO OF THE SHERMAN ACT RAMON A. KLITZKE* Section Two of the Sherman Act1 proscribes monopoliza- tion, a broad, ambiguous term that is susceptible of myriads of diverse interpretations in the complex world of business com- petition. Perceptions of monopolization as unlawful, anticom- petitive behavior vary widely, depending upon the various competitive methods utilized to achieve the monopolization. Some of these methods, such as the patent grant, are explicitly sanctioned by statutes and are therefore not unlawful. The patent grant, which is ostensibly a legal monopoly, 2 can be forged by its owner into a most powerful anticompetitive weapon that may be used to transcend the legal limits of its use. In numerous ways it may become a principal actor in the monopolization that is prohibited by Section Two. -

An Empirical Study of the Effects of Ex Ante Licensing Disclosure Policies on the Development of Voluntary Technical Standards

An Empirical Study of the Effects of Ex Ante Licensing Disclosure Policies on the Development of Voluntary Technical Standards by Jorge L. Contreras American University Washington College of Law Washington, DC for NISI National Institute of Standards and Technology U.S. Department of Commerce NIST Standards Services Group Under NIST Contract No. SB134110SEI033 This publication was produced as part of contract SB134110SEI033 with the National Institute of Standards and Technology. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Institute of Standards and Technology or the U.S. Government. GCR 11-934 Release Date: June 27, 2011 An Empirical Study of the Effects of Ex Ante Licensing Disclosure Policies on the Development of Voluntary Technical Standards Jorge L. Contreras Table of Contents Acknowledgements and Statement of Interests I. Executive Summary II. Background A. Development of Voluntary Technical Standards B. Patent Hold-Up in Standards-Setting C. SDO Patent Policies D. FRAND Licensing Requirements E. Ex Ante Disclosure ofLicensing Terms as a Proposed Solution F. Criticisms ofEx Ante Policy Policies G. SDO Adoption and Consideration ofEx Ante Policies 1. VITA 2. IEEE 3. ETSJ 4. Consortia (W3C and NGMN) 5. JETF and "Informal" Ex Ante Approaches III. Study Aims and Methodology A. Study Aims B. Methodology 1. SDOs Selected 2. Time Period 3. Historical Data 4. Survey Data IV. Findings and Analysis A. SDO Patent and Licensing Disclosures B. Number ofStandards C. Length ofStandardization Process D. Personal Time Commitment E. Membership F. Quality ofStandards G. Effect on Royalty Rates V. Conclusions Data Appendices List of References Ex Ante Standards Study Report Page i June 27,2011 Acknowledgements This study was funded by the u.s. -

ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT and INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS: Promoting Innovation and Competition

ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS: Promoting Innovation and Competition ISSUED BY THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION APRIL 2007 This Report should be cited as: U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE & FED. TRADE COMM’N, ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS: PROMOTING INNOVATION AND COMPETITION (2007). This Report can be accessed electronically at: www.usdoj.gov/atr/public/hearings/ip/222655.pdf www.ftc.gov/reports/index.shtm TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1: THE STRATEGIC USE OF LICENSING: UNILATERAL REFUSALS TO LICENSE PATENTS ................................................. 15 I. Introduction ......................................................... 15 II. The Kodak and CSU Decisions .......................................... 16 A. The Basic Facts and Holdings of the Cases .................. 16 B. Panelist Views on Kodak .................................. 17 C. Panelist Views on CSU ................................... 18 D. Ambiguity as to the Scope of the Patent Grant .............. 19 III. Policy Issues Relating to Unilateral Refusals to License ................... 20 A. Should Antitrust Law Accord Special Treatment to Patents? .. 21 B. Should Market Power Be Presumed with Patents? ........... 22 C. If an Antitrust Violation Were Found, Would There Be Workable Remedies for Unconditional, Unilateral Refusals to License Patents? .............................. 22 D. What Would Be the Effect of Liability for -

ISSM2020 –International Symposium on Semiconductor Manufacturing SPONSORSHIP December 15-16, 2020, Tokyo, Japan

ISSM2020 –International Symposium on Semiconductor Manufacturing SPONSORSHIP December 15-16, 2020, Tokyo, Japan Shozo Saito Chairman, ISSM2020 Organizing Committee Device & System Platform Development Center Co., Ltd. Shuichi Inoue, ATONARP INC. It is our great pleasure to announce that The 28th annual International Symposium on Semiconductor Manufacturing (ISSM) 2020 will be held on December 15-16, 2020 at KFC Hall, Ryogoku, Tokyo in cooperation with e-Manufacturing & Design Collaboration Symposium (eMDC) which is sponsored by TSIA with support from SEMI and GSA. The program will feature keynote speeches by world leading speakers, timely and highlighted topics and networking sessions focusing on equipment/materials/software/services with suppliers' exhibits. ISSM continues to contribute to the growth of the semiconductor industry through its infrastructure for networking, discussion, and information sharing among the world's professionals. We would like you to cooperate with us by supporting the ISSM 2020. Please see the benefit of ISSM2020 sponsorship. Conference Overview Date: December 15-16, 2020 Location: KFC (Kokusai Fashion Center) Hall 1-6-1 Yokoami Sumidaku, Tokyo 130-0015 Japan +81-3-5610-5810 Co-Sponsored by: IEEE Electron Devices Society Minimal Fab Semiconductor Equipment Association of Japan (SEAJ) Semiconductor Equipment and Materials International (SEMI) Taiwan Semiconductor Industry Association (TSIA) Endorsement by: The Japan Society of Applied Physics Area of Interest: Fab Management Factory Design & Automated Material -

NA Rohs Bittium Code Description Manufacturer Manufacturer Partnro Layout Cell Status QTY Ref Designator 1 Not Defined Belmont PWB 0

# NA RoHS Bittium Code Description Manufacturer Manufacturer partnro Layout cell Status QTY Ref Designator 1 Not Defined Belmont PWB 0. Proposal 1 PWB 2 EU RoHS,EU RoHS,China RoHS IC LEVEL TRANS TXB0104 WCSP Texas Instruments TXB0104YZTR BGA12_1.4X1.9_P0.5 0. Not Defined 4 D1,D4,D5,D16 3 EU RoHS IC LTE module VZM20Q SMD Sequans VZM20Q 0. Proposal 1 D15 4 Not Defined IC GNSS UFBGA48 Sony CXD5600GF 0. Proposal 1 D13 5 Yes IC UART+USB TI QFN32 Future Technology Devices International Ltd FT232RQ 0. Not Defined 1 D17 6 Yes IC MUX ANALOG TS5A3154 TI DSBGA8 Texas Instruments TS5A3154YZPR 0. Not Defined 1 D26 7 Not Defined IC Flash Serial 8Mbit WLCSP8 Winbond W25Q80EWBYIG 0. Proposal 1 D14 8 EU RoHS RF SAW FILTER GPS/GLONASS SMD Murata SAFFB1G58KA0F0A FILTER5_1.1X0.9 0. Proposal 2 Z2,Z3 9 EU RoHS RF SAW FILTER GPS+GLONASS SMD TDK‐EPC Corporation B39162B9839P810 1. Approved for Design 1 Z4 10 EU RoHS,China RoHS CRYSTAL 32.768 kHz 10PPM SMD Abracon corporation ABS06‐32.768KHZ‐9‐1‐T 1. Approved for Design 1 Y1 11 EU RoHS TCXO 16.368MHz ‐30/+85C +‐0.5PPM SMD NIHON DEMPA KOGYO CO. (NDK) NT2016SA‐16.368M‐NSA3506A 1. Approved for Design 1 Z1 12 EU RoHS IC RF AMP 1550‐1615MHz SMD Infineon Technologies BGA725L6 TSLP‐6‐2 0. Proposal 1 N7 13 EU RoHS,China RoHS IC REG LDO 1V8 LP5907 SOT‐23 Texas Instruments LP5907MFX‐1.8/NOPB SOT23‐5_H1.45 0. Not Defined 1 N2 14 Yes IC REG +3V3 TPS73633DBVT SOT23 Texas Instruments TPS73633DBVT SSOP5 0. -

Insufficiency of Antitrust As a Test for Patent Misuse

The Insufficie ncy of Antitrust Analysis for Patent Misuse Robin C. Feldman* Patent misuse lies at the intersection of patent and antitrust law. The history and conceptual overlap of patent law and antitrust law have left the doctrine of misuse hopelessly entangled with antitrust doctrines. In response, a number of scholars and legislators have argued for streamlin- ing the patent misuse inquiry by applying antitrust rules.1 Current court decisions have moved in this direction as well.2 The notion of applying antitrust rules to test for patent misuse has an appealing logic. Patent misuse can be defined as an improper attempt to expand a patent. Antitrust principles, among other things, restrict the improper expansion of monopolies. Shouldn’t courts be able to use anti- trust rules to identify an improper expansion of a patent monopoly? * Assistant Professor, U.C. Hastings College of the Law. I wish to thank Margreth Barrett, John Barton, Ash Bhagwat, Dan Burk, June Carbone, David Earp, Susan Freiwald, Paul Goldstein, Matthew Greene, Herbert Hovenkamp, Jeff Lefstin, Mark Lemley, Maura Rees, Ernest Young, and participants in the 2003 Intellectual Property Scholars’ Conference for their comments on prior drafts. I am grateful beyond measure to Linda Weir, U.C. Hastings Public Services Librarian, for her research and insights. I am also indebted to Amy Hsiao for research assistance on antitrust and to Gary Chang and Daniel Wan for research assistance on Reach-Through Royalties. 1. See, e.g., USM Corp. v. SPS Technologies, Inc., 694 F.2d 505, 512 (7th Cir. 1982); Windsurfing Int’l Inc. v. -

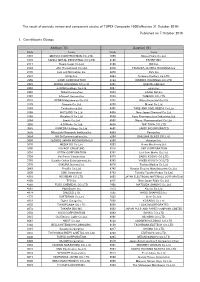

Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 31 October 2016) Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change Addition( 70 ) Deletion( 60 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1810 MATSUI CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 1868 Mitsui Home Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 2196 ESCRIT INC. 2117 Nissin Sugar Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2124 JAC Recruitment Co.,Ltd. 2418 TSUKADA GLOBAL HOLDINGS Inc. 2170 Link and Motivation Inc. 3079 DVx Inc. 2337 Ichigo Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 2359 CORE CORPORATION 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 2429 WORLD HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3205 DAIDOH LIMITED 2462 J-COM Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3667 enish,inc. 2485 TEAR Corporation 3834 ASAHI Net,Inc. 2492 Infomart Corporation 3946 TOMOKU CO.,LTD. 2915 KENKO Mayonnaise Co.,Ltd. 4221 Okura Industrial Co.,Ltd. 3179 Syuppin Co.,Ltd. 4238 Miraial Co.,Ltd. 3193 Torikizoku co.,ltd. 4331 TAKE AND GIVE. NEEDS Co.,Ltd. 3196 HOTLAND Co.,Ltd. 4406 New Japan Chemical Co.,Ltd. 3199 Watahan & Co.,Ltd. 4538 Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries,Ltd. 3244 Samty Co.,Ltd. 4550 Nissui Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd. 3250 A.D.Works Co.,Ltd. 4636 T&K TOKA CO.,LTD. 3543 KOMEDA Holdings Co.,Ltd. 4651 SANIX INCORPORATED 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 4809 Paraca Inc. 3654 HITO-Communications,Inc. 5204 ISHIZUKA GLASS CO.,LTD. 3666 TECNOS JAPAN INCORPORATED 5998 Advanex Inc. 3678 MEDIA DO Co.,Ltd. 6203 Howa Machinery,Ltd. 3688 VOYAGE GROUP,INC. 6319 SNT CORPORATION 3694 OPTiM CORPORATION 6362 Ishii Iron Works Co.,Ltd. 3724 VeriServe Corporation 6373 DAIDO KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3765 GungHo Online Entertainment,Inc. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

The Helios Operating System

The Helios Operating System PERIHELION SOFTWARE LTD May 1991 COPYRIGHT This document Copyright c 1991, Perihelion Software Limited. All rights reserved. This document may not, in whole or in part be copied, photocopied, reproduced, translated, or reduced to any electronic medium or machine readable form without prior consent in writing from Perihelion Software Limited, The Maltings, Charlton Road, Shepton Mallet, Somerset BA4 5QE. UK. Printed in the UK. Acknowledgements The Helios Parallel Operating System was written by members of the He- lios group at Perihelion Software Limited (Paul Beskeen, Nick Clifton, Alan Cosslett, Craig Faasen, Nick Garnett, Tim King, Jon Powell, Alex Schuilen- burg, Martyn Tovey and Bart Veer), and was edited by Ian Davies. The Unix compatibility library described in chapter 5, Compatibility,im- plements functions which are largely compatible with the Posix standard in- terfaces. The library does not include the entire range of functions provided by the Posix standard, because some standard functions require memory man- agement or, for various reasons, cannot be implemented on a multi-processor system. The reader is therefore referred to IEEE Std 1003.1-1988, IEEE Stan- dard Portable Operating System Interface for Computer Environments, which is available from the IEEE Service Center, 445 Hoes Lane, P.O. Box 1331, Pis- cataway, NJ 08855-1331, USA. It can also be obtained by telephoning USA (201) 9811393. The Helios software is available for multi-processor systems hosted by a wide range of computer types. Information on how to obtain copies of the Helios software is available from Distributed Software Limited, The Maltings, Charlton Road, Shepton Mallet, Somerset BA4 5QE, UK (Telephone: 0749 344345). -

Finding Aid to the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records, 1969-2002

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records Finding Aid to the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records, 1969-2002 Summary Information Title: Atari Coin-Op Division corporate records Creator: Atari, Inc. coin-operated games division (primary) ID: 114.6238 Date: 1969-2002 (inclusive); 1974-1998 (bulk) Extent: 600 linear feet (physical); 18.8 GB (digital) Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English, although there a few instances of Japanese. Abstract: The Atari Coin-Op records comprise 600 linear feet of game design documents, memos, focus group reports, market research reports, marketing materials, arcade cabinet drawings, schematics, artwork, photographs, videos, and publication material. Much of the material is oversized. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) have not been transferred, The Strong has permission to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Conditions Governing Access: At this time, audiovisual and digital files in this collection are limited to on-site researchers only. It is possible that certain formats may be inaccessible or restricted. Custodial History: The Atari Coin-Op Division corporate records were acquired by The Strong in June 2014 from Scott Evans. The records were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 114.6238.