Thesis Islamic Resurgence in Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whole-Genome Sequencing for Tracing the Genetic Diversity of Brucella Abortus and Brucella Melitensis Isolated from Livestock in Egypt

pathogens Article Whole-Genome Sequencing for Tracing the Genetic Diversity of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis Isolated from Livestock in Egypt Aman Ullah Khan 1,2,3 , Falk Melzer 1, Ashraf E. Sayour 4, Waleed S. Shell 5, Jörg Linde 1, Mostafa Abdel-Glil 1,6 , Sherif A. G. E. El-Soally 7, Mandy C. Elschner 1, Hossam E. M. Sayour 8 , Eman Shawkat Ramadan 9, Shereen Aziz Mohamed 10, Ashraf Hendam 11 , Rania I. Ismail 4, Lubna F. Farahat 10, Uwe Roesler 2, Heinrich Neubauer 1 and Hosny El-Adawy 1,12,* 1 Institute of Bacterial Infections and Zoonoses, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, 07743 Jena, Germany; AmanUllah.Khan@fli.de (A.U.K.); falk.melzer@fli.de (F.M.); Joerg.Linde@fli.de (J.L.); Mostafa.AbdelGlil@fli.de (M.A.-G.); mandy.elschner@fli.de (M.C.E.); Heinrich.neubauer@fli.de (H.N.) 2 Institute for Animal Hygiene and Environmental Health, Free University of Berlin, 14163 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Pathobiology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences (Jhang Campus), Lahore 54000, Pakistan 4 Department of Brucellosis, Animal Health Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Dokki, Giza 12618, Egypt; [email protected] (A.E.S.); [email protected] (R.I.I.) 5 Central Laboratory for Evaluation of Veterinary Biologics, Agricultural Research Center, Abbassia, Citation: Khan, A.U.; Melzer, F.; Cairo 11517, Egypt; [email protected] 6 Sayour, A.E.; Shell, W.S.; Linde, J.; Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Elzera’a Square, Abdel-Glil, M.; El-Soally, S.A.G.E.; Zagazig 44519, Egypt 7 Veterinary Service Department, Armed Forces Logistics Authority, Egyptian Armed Forces, Nasr City, Elschner, M.C.; Sayour, H.E.M.; Cairo 11765, Egypt; [email protected] Ramadan, E.S.; et al. -

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010 1. Please provide detailed information on Al Minya, including its location, its history and its religious background. Please focus on the Christian population of Al Minya and provide information on what Christian denominations are in Al Minya, including the Anglican Church and the United Coptic Church; the main places of Christian worship in Al Minya; and any conflict in Al Minya between Christians and the authorities. 1 Al Minya (also known as El Minya or El Menya) is known as the „Bride of Upper Egypt‟ due to its location on at the border of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is the capital city of the Minya governorate in the Nile River valley of Upper Egypt and is located about 225km south of Cairo to which it is linked by rail. The city has a television station and a university and is a centre for the manufacture of soap, perfume and sugar processing. There is also an ancient town named Menat Khufu in the area which was the ancestral home of the pharaohs of the 4th dynasty. 2 1 „Cities in Egypt‟ (undated), travelguide2egypt.com website http://www.travelguide2egypt.com/c1_cities.php – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 1. 2 „Travel & Geography: Al-Minya‟ 2010, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2 August http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384682/al-Minya – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 2; „El Minya‟ (undated), touregypt.net website http://www.touregypt.net/elminyatop.htm – Accessed 26 July 2010 – Page 1 of 18 According to several websites, the Minya governorate is one of the most highly populated governorates of Upper Egypt. -

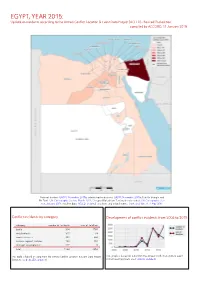

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Pdf (925.83 K)

Journal of Engineering Sciences, Assiut University, Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 1193-1207, September 2009. EVALUATION OF GROUNDWATER AQUIFER IN THE AREA BETWEEN EL-QUSIYA AND MANFALUT USING VERTICAL ELECTRIC SOUNDINGS (VES) TECHNIQUE 1 2 3 Waleed S.S. , Abd El-Monaim, A, E. , Mansour M.M. and El-Karamany M. F.3 1 Ministry of Water Resources (underground water sector) 2 Research Institute for Groundwater 3 Mining & Met. Dept., Faculty of Eng., Assiut University (Received August 5, 2009 Accepted August 17, 2009). The studied area is located northwest of Assiut city which represents a large part of the Nile Valley in Assiut governorate. It lies between latitudes 27° 15ƍ 00Ǝ and 27° 27ƍ 00Ǝ N, and longitudes 30° 42ƍ 30Ǝ to 31° 00ƍ E, covering approximately 330 square kilometers. Fifteen Vertical Electrical soundings (VES) were carried out to evaluate the aquifer in the study area. These soundings were arranged to construct three geoelectric profiles crossing the Nile Valley. Three cross sections were constructed along these profiles to detect the geometry and geoelectric characteristics of the quaternary aquifer based on the interpretation of the sounding curves and the comparison with available drilled wells. The interpretation showed that the thickness of the quaternary aquifer in the study area ranges between 75 and 300 m, in which the maximum thicknesses are detected around Manfalut and at the west of El-Qusiya. INTRODUCTION During the two last decades, there is a continuous demand for big amount of water necessary for the land expansion projects in Egypt. So, the development of groundwater resources receives special attention, since the groundwater reservoir underlying the Nile Valley and its adjacent desert areas acting as auxiliary source of water in Egypt. -

News Coverage Prepared For: the European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage Prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 Newspapers (29/11/2011) Election Coverage 2 Al Ahram Newspaper Page: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 Author: Mohamed Enz, Amany Maged, Sameh Lashen, Mohamed Hamada, Ibrahim Omran, Abdel-Gawad Ali, Wageh el-Saqqar, Badawi el-Sayed Negela, Amr Ali el- Far, Mohamed Zakaria, Nehad Samir, Ahmed el-Hawari, Essam Ali Refaat, Fekri Abdel-Salam, Nasser Geweda, Tareq Ismail, Rami Yassin, Mohamed Shear, Mohamed Abdel-Khaleq, Sherif Gaballah, Gamal Abul-Dahab, Ashraf Sadeq, Khaled Ahmed el-Motani, Ali Sham, Abdel-Gawad Tawfiq, Hala el-Sayed and Amal Awadallah Since the early morning of Monday, people have been lining up to cast their ballots in the first phase of the parliamentary elections, probably the first time in their lives. According to preliminary indications in the nine governorates, where the first stage of the elections are taking place, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice (FJP) and Salafist Al-Nour Party led the race in Cairo. Al-Nour Party seemed to be strongly competing in Alexandria, Fayoum and Kafr El- Sheikh. In the Southern Cairo constituency, voters stood in lines that lasted for over one kilometer. In Alexandria, vehicles belonging to candidates, wondered the streets to wake up voters since the small hours of Monday to cast their votes. -

Tutorial in English, Based on the Introduction of Islam

CENTRAL MUSLIM SPIRITUAL BOARD RUSSIA RUSSIAN ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY TUTORIAL IN ENGLISH, BASED ON THE INTRODUCTION OF ISLAM Initial training for educational institutions of secondary and higher level UFA, 2011 Published by the decision of the Editorial Board of the Russian Islamic University (Ufa) Tutorial in English, based on the introduction of Islam. - Ufa Publishing Division of the Russian Islamic University, 2011. - 000 pages. The book contains a mandatory minimum of knowledge, which every Muslim must possess: knowledge of the faith and order of worship to Allah. The book is intended for a wide range of readers. TsDUM Russia, 2011 PREFACE Endless thanks and praise to Allah the Most High, Who has created mankind and the entire universe with divine wisdom and for a great purpose. May blessings and peace be upon Muhammad, the means of compassion to the universe, the most distinguished intercessor and the most beloved Prophet of Allah the Lord, upon his family, upon his companions and upon all those who have followed and continue to follow his holy path. The content of this Introduction to Islam pertains to a branch of Islamic knowledge that provides information about faith (iman) and worship (ibadah). Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him (Sallallahu 'alayhi wa-sallam)1, said that it is compulsory for every Muslim man and woman to acquire knowledge. The knowledge (Introduction to Islam) in this manual gives essential information about faith (iman) and worship (ibadah) which will guide its adherent to happiness both in this world and in the Hereafter. One cannot become a complete and perfect Muslim without learning and believing these essentials, known in Arabic as Dharurah-al-Diniyyah (Necessary Rules of Religion). -

Inventory of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants of Coastal Mediterranean Cities with More Than 2,000 Inhabitants (2010)

UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG.357/Inf.7 29 March 2011 ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN Meeting of MED POL Focal Points Rhodes (Greece), 25-27 May 2011 INVENTORY OF MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS OF COASTAL MEDITERRANEAN CITIES WITH MORE THAN 2,000 INHABITANTS (2010) In cooperation with WHO UNEP/MAP Athens, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .........................................................................................................................1 PART I .........................................................................................................................3 1. ABOUT THE STUDY ..............................................................................................3 1.1 Historical Background of the Study..................................................................3 1.2 Report on the Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Mediterranean Coastal Cities: Methodology and Procedures .........................4 2. MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER IN THE MEDITERRANEAN ....................................6 2.1 Characteristics of Municipal Wastewater in the Mediterranean.......................6 2.2 Impact of Wastewater Discharges to the Marine Environment........................6 2.3 Municipal Wasteater Treatment.......................................................................9 3. RESULTS ACHIEVED ............................................................................................12 3.1 Brief Summary of Data Collection – Constraints and Assumptions.................12 3.2 General Considerations on the Contents -

A NEW OLD KINGDOM INSCRIPTION from GIZA (CGC 57163), and the PROBLEM of Sn-Dt in PHARAONIC THIRD MILLENNIUM SOCIETY

THE JOUR AL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 93 2007 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY ~IEWS, LONDON wei?'; 2PG ISSN 0307-5133 THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 93 2°°7 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LONDON WCIN zPG CONTENTS EDITORIAL FOREWORD Vll TELL EL-AMARNA, 2006-7 Barry Kemp THE DELTA SURVEY: MINUFIYEH PROVINCE, 2006-7 Joanne Rowland 65 THE GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY OF NORTH SAQQARA, 2001-7 . Ian Mathieson and Jon Dittmer. 79 AN ApPRENTICE'S BOARD FROM DRA ABU EL-NAGA . Jose M. Galan . 95 A NEW OLD KINGDOM INSCRIPTION FROM GIZA (CGC 57163), AND THE PROBLEM OF sn-dt IN PHARAONIC THIRD MILLENNIUM SOCIETY . Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia . · 117 A DEMOTIC INSCRIBED ICOSAHEDRON FROM DAKHLEH OASIS Martina Minas-Nerpel 137 THE GOOD SHEPHERD ANTEF (STELA BM EA 1628). Detlef Franket . 149 WORK AND COMPENSATION IN ANCIENT EGYPT David A. Warburton 175 SOME NOTES ON THE FUNERARY CULT IN THE EARLY MIDDLE KINGDOM: STELA BM EA 1164 . Barbara Russo . · 195 ELLIPSIS OF SHARED SUBJECTS AND DIRECT OBJECTS FROM SUBSEQUENT PREDICATIONS IN EARLIER EGYPTIAN . Carsten Peust · 211 THE EVIL STEPMOTHER AND THE RIGHTS OF A SECOND WIFE. Christopher J. Eyre . · 223 BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS FIGHTING KITES: BEHAVIOUR AS A KEY TO SPECIES IDENTITY IN WALL SCENES Linda Evans · 245 ERNEST SIBREE: A FORGOTTEN PIONEER AND HIS MILIEU Aidan Dodson . · 247 AN EARLY DYNASTIC ROCK INSCRIPTION AT EL-HoSH. Ilona Regulski . · 254 MISCELLANEA MAGICA, III: EIN VERTAUSCHTER KOPF? KONJEKTURVORSCHLAG FUR P. BERLIN P 8313 RO, COL. II, 19-20. Tonio Sebastian Richter. · 259 A SNAKE-LEGGED DIONYSOS FROM EGYPT, AND OTHER DIVINE SNAKES Donald M. -

Freedom of Religion and Belief in Egypt Quarterly Report (October - December 2008)

Freedom of Religion and Belief in Egypt Quarterly Report (October - December 2008) Freedom of Religion and Belief Program Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights January 2009 This report This report addresses several of the most significant developments seen in Egypt in the field of freedom of religion and belief in the months of October, November, and December of 2008. The report observes continued sectarian tension and violence all over Egypt and documents cases in the governorates of Cairo, Alexandria, Qalyoubiya, Sharqiya, Kafr al-Sheikh, Minya, and Luxor. As usual, Minya accounted for the lion’s share of incidents of sectarian violence, with cases in the district of Matay, the village of Kom al-Mahras, and the district of Abu Qurqas, as well as events in the village of al-Tayiba in the Samalut district in October. The latter were the worst of the fourth quarter of 2008, leaving one Christian dead and four other people injured, among them one Muslim. Homes, lands, and property were also torched and damaged. The report also notes increased tensions and clashes as a result of Copts establishing “service centers” to use for social occasions, prayers, or religious lessons in neighborhoods and villages that have no nearby churches or in cases where Copts have failed to obtain permits to build a new church or renovate an existing church. The report discusses several instances in which the establishment of such centers, or rumors that attempts were being made to convert them into churches, led to sectarian clashes. Events in November in the Ain Shams area of Cairo received the most media coverage in this regard, but two similar incidents took place in the village of Kafr Girgis in the Minya al-Qamh district of Sharqiya and in the al-Iraq village in Alexandria’s al- Amiriya neighborhood. -

MOST ANCIENT EGYPT Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu MOST ANCIENT EGYPT oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber MOST ANCIE NT EGYPT William C. Hayes EDITED BY KEITH C. SEELE THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO & LONDON oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-17294 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada © 1964, 1965 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1965. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER HAYES 1903-1963 oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu INTRODUCTION WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER HAYES was on the day of his premature death on July 10, 1963 the unrivaled chief of American Egyptologists. Though only sixty years of age, he had published eight books and two book-length articles, four chapters of the new revised edition of the Cambridge Ancient History, thirty-six other articles, and numerous book reviews. He had also served for nine years in Egypt on expeditions of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the institution to which he devoted his entire career, and more than four years in the United States Navy in World War II, during which he was wounded in action-both periods when scientific writing fell into the background of his activity. He was presented by the President of the United States with the bronze star medal and cited "for meritorious achievement as Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. VIGILANCE ... in the efficient and expeditious sweeping of several hostile mine fields.., and contributing materially to the successful clearing of approaches to Okinawa for our in- vasion forces." Hayes' original intention was to work in the field of medieval arche- ology. -

Discharge from Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants Into Rivers Flowing Into the Mediterranean Sea

UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG. 334/Inf.4/Rev.1 15 May 2009 ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN MED POL Meeting of MED POL Focal Points Kalamata (Greece), 2- 4 June 2009 DISCHARGE FROM MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS INTO RIVERS FLOWING INTO THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA UNEP/MAP Athens, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................1 PART I.......................................................................................................................................3 1. ΑΒOUT THE STUDY............................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Historical Background of the Study .....................................................................................3 1.2 Report on the Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Mediterranean Coastal Cities .........................................................................................................................................4 1.3 Methodology and Procedures of the present Study ............................................................5 2. MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER IN THE MEDITERRANEAN..................................................... 8 2.1 Characteristics of Municipal Wastewater in the Mediterranean ..........................................8 2.2 Impacts of Nutrients ............................................................................................................9 2.3 Impacts of Pathogens..........................................................................................................9 -

The Impact of the Arab Conquest on Late Roman Settlementin Egypt

Pýý.ý577 THE IMPACT OF THE ARAB CONQUEST ON LATE ROMAN SETTLEMENTIN EGYPT VOLUME I: TEXT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY CAMBRIDGE This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Cambridge, March 2002 ALISON GASCOIGNE DARWIN COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE For my parents with love and thanks Abstract The Impact of the Arab Conquest on Late Roman Settlement in Egypt Alison Gascoigne, Darwin College The Arab conquest of Egypt in 642 AD affected the development of Egyptian towns in various ways. The actual military struggle, the subsequent settling of Arab tribes and changes in administration are discussed in chapter 1, with reference to specific sites and using local archaeological sequences. Chapter 2 assesseswhether our understanding of the archaeological record of the seventh century is detailed enough to allow the accurate dating of settlement changes. The site of Zawyet al-Sultan in Middle Egypt was apparently abandoned and partly burned around the time of the Arab conquest. Analysis of surface remains at this site confirmed the difficulty of accurately dating this event on the basis of current information. Chapters3 and 4 analysethe effect of two mechanismsof Arab colonisation on Egyptian towns. First, an investigation of the occupationby soldiers of threatened frontier towns (ribats) is based on the site of Tinnis. Examination of the archaeological remains indicates a significant expansion of Tinnis in the eighth and ninth centuries, which is confirmed by references in the historical sources to building programmes funded by the central government. Second, the practice of murtaba ` al- jund, the seasonal exploitation of the town and its hinterland for the grazing of animals by specific tribal groups is examined with reference to Kharibta in the western Delta.