Russian Literature: Recommended Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Was First Assigned to the American Embassy in Moscow in 1961

Remembering Vasya Aksyonov With Bella Akhmadulina and Vasily Aksyonov Photo by Rebecca Matlock I was first assigned to the American Embassy in Moscow in 1961. This was when the “Generation of the Sixties” (шестидесятники) was beginning to rise in prominence. It was an exciting development for those of us who admired Russian literature and were appalled at the crushing of creativity brought on by Stalin’s enforced “socialist realism.” I read Vasya’s Starry Ticket with great interest, particularly since it seemed to deal with the same theme as the American writer J.D. Salinger did in his The Catcher in the Rye—a disaffected adolescent who runs away from humdrum reality to what he imagines will be a more glamorous life elsewhere. I then began to follow the stories Vasya published in Yunost’. “Oranges from Morocco” was one that impressed me. Much later, he told me that the story was inspired by an experience while he was in school in Magadan. The original title had been “Oranges from Israel.” He was instructed to replace Israel with Morocco in the title after the Soviet Union broke relations with Israel following the 1967 war. Although I was a young diplomat not much older than Vasya, my academic specialty had been Russian literature and I was eager to meet as many Soviet writers as possible. In fact, one of the reasons I entered the American Foreign Service was because it seemed, while Stalin was still alive, one of the few ways an American could live for a time in the Soviet Union and thus have direct contact with Russian culture. -

Warrior, Philosopher, Child: Who Are the Heroes of the Chechen Wars?

Warrior, Philosopher, Child: Who are the Heroes of the Chechen Wars? Historians distinguish between the two Chechen wars, first in 1994-1995 under Yeltsin’s presidency, and second in 1999-2000, when Vladimir Putin became the Prime Minister of Russia and was mainly responsible for military decision-making. The first one was the result of the Soviet Union dissolution, when Chechnya wanted to assert its independence on the Russian Federation. The second one started with the invasion of Dagestan by Shamil Basaev’s terrorist groups, and bombings in Moscow, Volgodonsk and the Dagestani town Buynaksk. It remains unclear what exactly led to a Russian massive air-campaign over Chechnya in 1999. Putin declared the authority of Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov and his parliament illegitimate, and Russians started a land invasion. In May 2000, Putin established direct rule of Chechnya. However, guerrilla war never stopped. Up to now there has been local ongoing low-level insurgency against Ramzan Kadyrov, the Head of the Chechen Republic. Who was drafted to fight in the Chechen Wars? Mainly, young people from neighbouring regions of Russia, who were poorly trained. Russian troops suffered severe losses, since they were ill-prepared. Because of lack of training and experience, Russian forces often attacked random positions, causing enormous casualties among the Chechen and Russian civilian population. The Russian-Chechen Friendship Society set their estimate of the total death toll in two wars at about 150,000 to 200,000 civilians1. If the first war received extensive international coverage, the second got considerably 1 Wikipedia. Retrieved March 30, 2017 from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Chechen_War. -

The Cases of Venedikt Erofeev, Kurt Vonnegut, and Victor Pelevin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Western Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-21-2012 12:00 AM Burying Dystopia: the Cases of Venedikt Erofeev, Kurt Vonnegut, and Victor Pelevin Natalya Domina The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Calin-Andrei Mihailescu The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Natalya Domina 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Domina, Natalya, "Burying Dystopia: the Cases of Venedikt Erofeev, Kurt Vonnegut, and Victor Pelevin" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 834. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/834 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BURYING DYSTOPIA: THE CASES OF VENEDIKT EROFEEV, KURT VONNEGUT, AND VICTOR PELEVIN (Spine Title: BURYING DYSTOPIA) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Natalya Domina Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada Natalya Domina 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ____________________________ ________________________________ Prof. -

The Founder Effect

Baen Books Teacher Guide: The Founder Effect Contents: o recommended reading levels o initial information about the anthology o short stories grouped by themes o guides to each short story including the following: o author’s biography as taken from the book itself o selected vocabulary words o content warnings (if any) o short summary o selected short assessment questions o suggested discussion questions and activities Recommended reading level: The Founder Effect is most appropriate for an adult audience; classroom use is recommended at a level no lower than late high school. Background: Published in 2020 by Baen Books, The Founder Effect tackles the lens of history on its subjects—both in their own words and in those of history. Each story in the anthology tells a different part of the same world’s history, from the colonization project to its settlement to its tragic losses. The prologue provides a key to the whole book, serving as an introduction to the fictitious encyclopedia and textbook entries which accompany each short story. Editors’ biographies: Robert E. Hampson, Ph.D., turns science fiction into science in his day job, and puts the science into science fiction in his spare time. Dr. Hampson is a Professor of Physiology / Pharmacology and Neurology with over thirty-five years’ experience in animal neuroscience and human neurology. His professional work includes more than one hundred peer-reviewed research articles ranging from the pharmacology of memory to the first report of a “neural prosthetic” to restore human memory using the brain’s own neural codes. He consults with authors to put the “hard” science in “Hard SF” and has written both fiction and nonfiction for Baen Books. -

01 Schmid Russ Medien.Indd

Facetten der Medienkultur Band 6 Herausgegeben von Manfred Bruhn Vincent Kaufmann Werner Wunderlich Ulrich Schmid (Hrsg.) Russische Medientheorie Aus dem Russischen von Franziska Stöcklin Haupt Verlag Bern Stuttgart Wien Ulrich Schmid (geb. 1965) studierte Slavistik, Germanistik und Politologie an den Universitäten Zürich, Heidelberg und Leningrad. Seit 1993 arbeitet er als freier Mitarbeiter im Feuilleton der Neuen Zürcher Zeitung NZZ. 1995–1996 forschte er als Visiting Fellow an der Harvard University. Von 1992–2000 war er Assistent, von 2000–2003 Assistenzprofessor am Slavischen Seminar der Universität Basel. 2003–2004 Assistenzprofessor am Institut für Slavistik der Universität Bern, seit 2005 Ordinarius für slavische Literaturwissenschaft an der Ruhr-Universität Bochum. Publiziert mit der freundlichen Unterstützung durch die Schweizerische Akademie der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften (SAGW) Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek: Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Na- tionalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. ISBN 3-258-06762-7 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Copyright © 2005 Haupt Verlag Berne Jede Art der Vervielfältigung ohne Genehmigung des Verlages ist unzulässig. Umschlag: Atelier Mühlberg, Basel Satz: Verlag Die Werkstatt, Göttingen Printed in xxx http://www.haupt.ch Inhalt Einleitung Ulrich Schmid Russische Medientheorien xx Grundlagen einer Medientheorie in Russland Nikolai Tschernyschewski Die ästhetischen Beziehungen der Kunst zur Wirklichkeit (1855) xx Lew Tolstoi Was ist Kunst? (1899) xx Pawel Florenski Die umgekehrte Perspektive (1920) xx Josif Stalin Der Marxismus und die Fragen der Sprachwissenschaft (1950) xx Michail Bachtin Das Problem des Textes in der Linguistik, Philologie und anderen Geisteswissenschaften. Versuch einer philosophischen Analyse (1961) xx Juri Lotman Theatersprache und Malerei. -

Soviet Jewry (8) Box: 24

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Green, Max: Files Folder Title: Soviet Jewry (8) Box: 24 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ Page 3 PmBOMBR.S OP CONSCIBNCB J YLADDllll UPSIDTZ ARRESTED: January 8, 1986 CHARGE: Anti-Soviet Slander DATE OF TRIAL: March 19, 1986 SENTENCE: 3 Years Labor Camp PRISON: ALBXBI KAGAllIIC ARRESTED: March 14, 1986 CHARGE: Illegal Possession of Drugs DATE OF TRIAL: SENTENCE: PRISON: UCHR P. O. 123/1 Tbltsi Georgian, SSR, USSR ALEXEI llUR.ZHBNICO (RE)ARRBSTBD: June 1, 1985 (Imprisoned 1970-1984) CHARGE: Parole Violations DA TB OF TRIAL: SENTENCE: PRISON: URP 10 4, 45/183 Ulitza Parkomienko 13 Kiev 50, USSR KAR.IC NBPOllNIASHCHY .ARRESTED: October 12, 1984 CHARGE: Defaming the Soviet State DA TB OF TRIAL: January 31, 1985 SENTENCE: 3 Years Labor Camp PRISON: 04-8578 2/22, Simferopol 333000, Krimskaya Oblast, USSR BETZALBL SHALOLASHVILLI ARRESTED: March 14, 1986 CHARGE: Evading Mllltary Service DA TE OF TRIAL: SENTENCE: PRISON: L ~ f UNION OF COUNCILS FOR SOVIET JEWS 1'411 K STREET, NW • SUITE '402 • WASHINGTON, DC 2<XX>5 • (202)393-44117 Page 4 PIUSONB'R.S OP CONSCIBNCB LBV SHBPBR ARRESTED: -

A10marsch Forum 28Korr

Citation for published version: Marsh, R 2011, 'The “new political novel” by right-wing writers in post-Soviet Russia', Forum für osteuropäische Ideen- und Zeitgeschichte, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 159-187. Publication date: 2011 Link to publication University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 III. Anti-Western Tendencies in Post-Soviet Russia and Their Historical Roots (1) Rosalind Marsh The “New Political Novel” by Right-Wing Writers in Post-Soviet Russia Most Western commentators claim that literature and politics have moved irrevocably apart into two separate spheres in the post-Soviet period. However, I have argued in my recent book (Marsh 2007) that the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the new millennium witnessed the emergence of what I would term “the new political novel,” encompassing writers of many different political viewpoints – from Aleksandr Prokhanov’s national- patriotic and anarcho-communist attacks on governmental mechanisms of oppression to Aleksandr Tsvetkov’s hostility to global capitalist production and the power of the mass media. This suggests that Russian literature has once again become politicized, perhaps because writers living in Putin’s “managed democracy” feel that they are as remote from the levers of power as they were in the Soviet period. -

Spinning Russia's 21St Century Wars

Research Article This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative The RUSI Journal Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerivatives License (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Spinning Russia’s 21st Century Wars Zakhar Prilepin and his ‘Literary Spetsnaz’ Julie Fedor In this article, Julie Fedor examines contemporary Russian militarism through an introduction to one of its most high-profile representatives, the novelist, Chechen war veteran and media personality Zakhar Prilepin. She focuses on Prilepin’s commentary on war and Russian identity, locating his ideas within a broader strand of Russian neo-imperialism. he Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 brand of militarism that has come to pervade the and the war in the Donbas which began Russian media landscape, Prilepin warrants our T that same year have been accompanied by attention. Studying his career and output can help a remarkable drive to mobilise cultural production to illuminate the context and underpinnings of the in Russia in support of a new brand of state- domestic support for the official military doctrine sponsored militarism. Using a variety of media and policy that is more commonly the subject of platforms and reaching mass popular audiences, scholarship on Russian military and security affairs. a range of cultural celebrities – actors, writers, This article focuses on Prilepin’s commentary rock stars, tabloid war correspondents – have on the nature of war and Russian identity, locating played a key role in framing and shaping domestic his ideas within a broader strand of Russian perceptions of Russia’s 21st Century wars. Despite neo-imperialism in which war is claimed as a vital their prominence in Russian media space, their source of belonging, power and dignity.1 It shows activities have received surprisingly little scholarly how the notion of a special Russian relationship attention to date. -

Victor Pelevin – Nhà Văn Của Kỷ Nguyên Mới

ISSN: 1859-2171 TNU Journal of Science and Technology 205(12): 47 - 52 e-ISSN: 2615-9562 VICTOR PELEVIN – NHÀ VĂN CỦA KỶ NGUYÊN MỚI Lưu Thu Trang Trường Đại học Sư phạm – ĐH Thái Nguyên TÓM TẮT Victor Pelevin là một trong số các nhà văn hậu hiện đại Nga có mặt trong danh sách 1000 nhân vật có tầm ảnh hưởng nhất của văn hóa hiện đại được bình chọn bởi tạp chí French Magazine của Pháp. Tuy vậy, tên tuổi và tác phẩm của ông chưa được nhiều độc giả Việt Nam biết đến. Bài báo này được viết nhằm mục đích giới thiệu những thông tin cơ bản nhất về con người và tác phẩm của Victor Pelevin. Các kết quả thu được nhờ tổng hợp các bài viết về Victor Pelevin trên các tạp chí, sách báo văn học. Tác giả Victor Pelevin bắt đầu xuất bản truyện ngắn đầu tiên vào năm 1989 và liên tục cho ra đời các tác phẩm mới. Theo một khảo sát trên trang OpenSpace.ru năm 2009, nhà văn đã được công nhận là trí thức có ảnh hưởng nhất của Liên bang Nga. Các tác phẩm của ông phản ánh một cách đa dạng các chủ đề về lịch sử và hiện thực xã hội, về thế giới côn trùng và động vật, về sự tự do... Ở Victor Pelevin có một sự kế thừa truyền thống tạo ra từ A. Chekhov vào cuối thế kỉ XIX, đầu thế kỉ XX. Các thông tin cơ bản về Victor Pelevin có ý nghĩa như một nghiên cứu khái lược, làm cơ sở tham khảo cho các nghiên cứu chuyên sâu về ông cũng như về văn học Nga đương đại. -

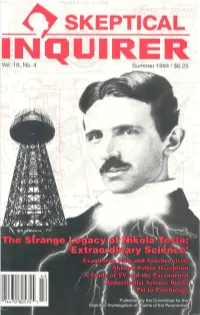

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Lines of Departure Free

FREE LINES OF DEPARTURE PDF Marko Kloos | 328 pages | 28 Jan 2014 | Amazon Publishing | 9781477817407 | English | Seattle, United States Lines of Departure - Marko Kloos - Google книги Vicious interstellar Lines of Departure with an indestructible alien species. Bloody civil war over the last habitable zones of the cosmos. Political Lines of Departure, militaristic police forces, dire threats to the Solar System…. Humanity is on the ropes, and after years of fighting a two-front war with losing odds, so is North American Defense Corps officer Andrew Grayson. He dreams of dropping out of the service one day, alongside his pilot girlfriend, but as warfare consumes entire planets and conditions on Earth deteriorate, he wonders if there will be anywhere left for them to go. After surviving a disastrous space-borne assault, Grayson is reassigned to a ship bound for a distant colony—and Lines of Departure with malcontents and troublemakers. His most dangerous battle has just begun. When dealing with a masterpiece, only the best will do. And as anyone who has read the previous two collected volumes of the ongoing series can Lines of Departure, the result has been a stunning tour de force faithful in every respect to its brilliant original. The competing teams of astronauts sent to explore the asteroid Keanu discovered it was, in fact, a giant spacecraft with an alien crew carrying a plea for help. A brave new frontier beckons. But it will come at a price. Without warning, the aliens transport small groups of humans to the vast interior habitats of Keanu. Their first challenge is to survive. -

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Resistant Postmodernisms: Writing Postcommunism in Armenia and Russia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/32m003t0 Author Douzjian, Myrna Angel Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Resistant Postmodernisms: Writing Postcommunism in Armenia and Russia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Myrna Angel Douzjian 2013 @ Copyright by Myrna Angel Douzjian 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Resistant Postmodernisms: Writing Postcommunism in Armenia and Russia by Myrna Angel Douzjian Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor David W. MacFadyen, Co-Chair Professor Kathleen L. Komar, Co-Chair Many postcolonial scholars have questioned the ethics of postmodern cultural production. Critics have labeled postmodernism a conceptual dead end – a disempowering aesthetic that does not offer a theory of agency in response to the workings of empire. This dissertation enters the conversation about the political alignment of postmodernism through a comparative study of postcommunist writing in Armenia and Russia, where the debates about the implications and usefulness of postmodernism have been equally charged. This project introduces the directions in which postcommunist postmodernisms developed in Armenia and