Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:41:49Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Race and Class Analysis of Learning in the Organic Farming Movement Catherine Etmanski Royal Roads University, Canada

Australian Journal of Adult Learning Volume 52, Number 3, November 2012 A critical race and class analysis of learning in the organic farming movement Catherine Etmanski Royal Roads University, Canada The purpose of this paper is to add to a growing body of literature that critiques the whiteness of the organic farming movement and analyse potential ramifications of this if farmers are to be understood as educators. Given that farmers do not necessarily self-identify as educators, it is important to understand that in raising this critique, this paper is as much a challenge the author is extending to herself and other educators interested in food sovereignty as it is to members of the organic farming movement. This paper draws from the author’s personal experiences and interest in the small-scale organic farming movement. It provides a brief overview of this movement, which is followed by a discussion of anti-racist food scholarship that critically assesses the inequities and inconsistencies that have developed as a result of hegemonic whiteness within the movement. It then demonstrates how a movement of Indigenous food sovereignty is emerging parallel to the organic farming movement and how food sovereignty is directly Catherine Etmanski 485 related to empowerment through the reclamation of cultural, spiritual, and linguistic practices. Finally, it discusses the potential benefits of adult educators interested in the organic farming movement linking their efforts to a broader framework of food sovereignty, especially through learning to become better allies with Indigenous populations in different parts of the world. Introduction Following the completion of my doctoral studies in 2007, I sought out an opportunity to work on a small organic farm. -

Chapter 6 Motivations for Food System

Durham E-Theses `Local Food' Systems in County Durham: The capacities of community initiatives and local food businesses to build a more resilient local food system MYCOCK, AMY,ELIZABETH How to cite: MYCOCK, AMY,ELIZABETH (2011) `Local Food' Systems in County Durham: The capacities of community initiatives and local food businesses to build a more resilient local food system , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3304/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 „Local Food‟ Systems in County Durham: The capacities of community initiatives and local food businesses to build a more resilient local food system Amy Mycock This thesis provides a critical assessment of the capacities of „local food‟ businesses and community-led local food initiatives - in County Durham, North East England - to build resilience into our food systems. -

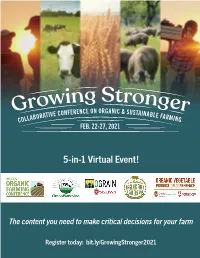

5-In-1 Virtual Event !

5-in-1 Virtual Event ! The content you need to make critical decisions for your farm Register today: bit.ly/GrowingStronger2021 EVENT SPONSORS 5-in-1 Virtual Event: This conference is all about collaboration. These outstanding businesses have stepped up to make sure the “show goes on.” MOSES Organic Farming Conference Our community couldn’t gather without their support. Please join us GrassWorks Grazing Conference in thanking them and visiting their booths in the online exhibit area. OGRAIN Conference Midwest Organic Pork Conference Organic Vegetable Production Conference Feb. 22-27, 2021 Build your skills and nurture your passion for organic and sustainable farming! Register today to grow stronger Acres U.S.A. Nature Safe Fertilizer with your community: Agricultural Flaming Innovations Nature’s International Certification Services Albert Lea Seed NutraDrip Irrigation Douglas Plant Health Ohio Earth Food bit.ly/GrowingStronger2021 Dr. Bronner’s Organic Farmers Agency for DRAMM Corporation Relationship Marketing (OFARM) F.W. Cobs Peace Corps Response Food Finance Institute Royal Lee Organics Gallagher Animal Management North America SQM North America Grain Millers, Inc. Sunrise Foods International, Inc. Questions? High Mowing Organic Seeds Suståne Natural Fertilizer, Inc. Kreher Family Farms Vermont Compost Call the Registration Team: Man@Machine | Treffler Organic Machinery Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, 888-90-MOSES MOSA Certified Organic Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) 3 Michael Perry SCHEDULE Bestselling Author, Humorist, Playwright, Radio Show Host CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Perry’s bestselling memoirs in- Growing Stronger is packed with opportunities to connect clude Population: 485 and Truck: and grow your farming skills, plus find resources for the grow- A Love Story. -

WWOOF UK Newsletter

W W O O F UK NEWS worldwide opportunities on organic farms issue 258 spring 2018 inside: Taster Days UK Immigration Rules vintage WWOOFers WWOOF welcomes 16 year-olds interest free loans for hosts? wwoof uk news issue 258 page 2 editorial WWOOFing medical emergency and advises us on how welcome to the winter 2017 to plan for the worst, page 11. edition of WWOOF UK News WWOOFer Carolyn Gemson shares some of the side effects of WWOOFing she’s found, page 9 and vintage Spring should be officially with us by the time you read WWOOFer Martin talks to Chief Exec Scarlett, page 4. this, and I’m hoping it’s going to be a gentle and replen- Mr Fluttergrub tells how to tend to and propagate Jeru- ishing one after what feels like a long, cold winter. We salem Artichokes on page 6 and allows me to introduce have some new initiatives to start the growing year the word ‘fartichocke’ into the newsletter which gives with – our first Taster Day was sold out well in advance and we are looking for more hosts willing to encourage delight. Childish, I know. non-members into the WWOOFing fold, page 3. WWOOF UK trustee Katie Hastings shares details of the UK and Ireland Seed Sovereignty Programme on page The minimum age for WWOOFer volunteers has been 10 and on page 8 Phil Moore, ex-WWOOFer and Eco- reduced to 16; we explain the thoughts and intentions logical Land Alliance friend, tries to persuade us to get behind that on page 11 while on page 7 we offer a on our bikes and go dragon dreaming in Wales. -

The Charter of WWOOF Belgium

The charter of WWOOF Belgium 1. OUR VALUES, OUR PHILOSOPHY, AND THE GOALS WE WISH TO PROMOTE Create a direct link between consumer and producer, between city dwellers who don’t live in connection with the land, and rural dwellers who live alongside her. Provide an opportunity to learn about the lifestyle and conditions of the biological farmer who lives from his/her agricultural activities. Offer timely assistance to farmers and any person who engages in an ecological project. Discover the know-how and skills, and the cultivation and commercial methods of organic farmers who produce healthy food for a local population. Raise awareness of the value and importance of food in our lives. Promote a philosophy of solidarity, mutual assistance and non-monetary exchanges. Offer opportunities to experience a way of life in ecological balance and conscientious of a respectful ecological footprint. Provide an opportunity to discover the ‘real’ Belgium to people from around the world. 2. A HOST Their profile The profile of a host is very varied: an organic farmer, an individual maintaining her/his organic garden, or undertaking an eco-construction project, a craftsperson ... What is common to all is the desire to share and transmit knowledge (over agriculture and organic gardening, different philosophies such as agro-ecology, permaculture, biodynamics, eco- construction…). In addition, a host likes to share his/her lifestyle (everyday ecological practices, family and neighbourhood ties, projects for the future). The charter of WWOOF Belgium - page 1 10/28/2019 A host never sees a wwoofer as an employee with a duty of profitability and / or subordination. -

WWOOF UK Newsletter

W W O O F UK NEWS worldwide opportunities on organic farms issue 260 autumn 2018 inside: WWOOFing with alpacas taster days—a success story calendar countdown commences WWOOFing in the Scottish Islands #penntopaper on the plot with Mr Fluttergrub farm hack and CSA gathering beaver reintroduction update wwoof uk news issue 260 page 2 editorial We’ve had real success with our experimental taster welcome to the autumn 2018 days this year – on page 7 we tell you how they’ve edition of WWOOF UK News gone and how to get involved in future events. Page 8 brings news of a revised approach to our AGM and re- I hope the summer has been kind to you – many people gional gatherings while on page 3 we are delighted to will have revelled in the consistent bright weather announce that we will be making a calendar for 2019 much of the country has had, with all the opportunities available and give you details of how to get yours. it’s given to plan outdoor events with confidence and Mr Fluttergrub is looking on the bright side of the re- enjoy the longer days. At the same time there have cent high temperatures and celebrates a bumper crop been major challenges associated with the heat and of aubergines – he tells us how to grow and nurture lack of rainfall. We’d love to hear how it’s been for our them for best cropping, page 6. members and what part WWOOFing has played. And what could ever be cuter than WWOOFing with We have a couple of new features in this issue. -

Spirituality, Nature and Self-Transformation on the WWOOF Farm

Spirituality, Nature And Self-Transformation On The WWOOF Farm MSc Thesis Malou ter Horst (900125366010) Master Forest Nature Conservation (MFN) Forest Nature Conservation Policy group (FNP), Wageningen University Under supervision of Clemens Driessen & Birgit Elands 20th May 2016 1 Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 6 List of tables ............................................................................................................................................ 7 List of figures ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 8 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1. Spirituality, self-transformation and nature ......................................................................... 10 1.2. The WWOOF organization .................................................................................................... 12 1.3. Tourism in the cultivated landscape ..................................................................................... 13 1.4. WWOOF: from motivations to outcomes ............................................................................ -

Outdoor Education Through Ecological Living for Change in Way of Life

Department of Arts, Craft and Design Center for Environmental and Outdoor Education David Schott Outdoor Education through Ecological Living for Change in Way of Life Master in Outdoor Environmental Education and Outdoor Life Thesis 15 ECTS Supervisor: Dr. Dusan Bartunek LiU-ESI-MOE-D--06/008--SE Estetiska institutionen Avdelning, Institution Datum Division, Department Date Department of Arts, Craft and Design S-581 83 LINKÖPING 2006-05-20 SWEDEN Språk Rapporttyp ISBN Language Report category English ISRN LiU-ESI-MOE-D--06/008--SE Thesis Serietitel och serienrummer ISSN Title of series, numbering ____ URL för elektronisk version Titel Title Outdoor Education through Ecological Living for Change in Way of Life Författare Author David Schott Sammanfattning Abstract Human are currently living in a way that profoundly affects the planet, and the lives of future generations. Our value system promotes economic gain over environmental health. We are taking more than we are giving back, stretching beyond the limits of sustainability. Earth cannot sustain the current human lifestyle under these conditions. This is paired with the fact that the current system of education focuses on producing economically productive individuals instead of environmentally and socially aware persons who carefully consider the impacts of their actions. This study examines the capacity for “ecological living” to use outdoor education as a tool for changing the present human way of life. Thirty three ecological farms responded to a questionnaire examining the importance each placed on current vs. alternative values. The respondents also answered questions displaying the relationship between life on their farms and the key components of outdoor education. -

Geographical Indications

Who can provide me with advice and guidance throughout the process? Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine Sharon Murphy / Tara Keogh Geographical Indications [email protected] Food Industry Development Division 6 West, Agriculture House Kildare Street Dublin 2 Protection of Food and Drink www.agriculture.gov.ie names Bord Bia Declan Coppinger [email protected] Clanwilliam Court Lower Mount Street Dublin 2 01 614 2202 www.bordbia.ie Food Industry Development Division Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine Bord Iscaigh Mara (BIM) August 2012 Catherine Morrison [email protected] Environment and Quality Section Head +353 (1) 2144 118 Making the link between www.bim.ie product and place Teagasc Pat Daly [email protected] Head of Food Industry Development http://www.agriculture.gov.ie/agri- foodindustry/geographicalindicationsprotectedfooda +353 1 8059500 nddrinknames/ www.teagasc.ie What are Geographical Indications? What kinds of GI Protection are there? Timoleague Brown Pudding - Brown pudding The Quality policy of the EU is based on the strong Protected Designations of Origin (PDO) made using a local traditional recipe within the link between the product and its territory. Product is wholly made within geographical area. Some ingredients are sourced the Geographical area. Product outside of the geographical area. Geographical Indications are a type of is produced, processed and intellectual property. PDO, PGI and TSG prepared within the defined Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG) designations, linked to a region or to a geographical area. The product where the product must be production method, are protected from possesses characteristics are essentially due to traditional (25 years/handed imitation and misuse of the name. -

Fiche Irlande

Les spécialités culinaires Irlande Plats Accords Dublin Oysters and Guiness : huitres accompagnées d'une pinte de Guinness. Haddie and leek pie : Tourte au haddock et aux poireaux. Giblet soup, fish pie : saumon et crevettes Présentation du Pays gratinés au four. ■ Il s'agit d'une république parlementaire qui s'étend sur Fish and Chips. les 26 des 32 comtés historiques qu'elle partage avec Oie de la St Michel : oie farcie. l'Irlande du nord. Elle fait partie des nations "celtiques". Irish Stew : ragoût de mouton et de ■ L'anglais et l'Irlandais sont les deux langues officielles. pommes de terre. ■ Pays assez jeune puisqu'il est devenue indépendant Dublin coddle : saucisse et lard pochés (autoproclamée) en 1919. avec des pommes de terre. ■ 85 % de la population est catholique. Cocannon : chou râpé, pommes de terre et Us et coutumes navets bouillis. Petit Il est très copieux et accompagné de thé. Il se Apple pie. Déjeuner compose de céréales (porridge), toasts, bacon, Irish whiskey trifle : génoise composée de saucisse, jus d'orange… macédoine de fruits macérés dans un Déjeuner Comme les anglais, il se compose souvent d'un whiskey, servi avec une crème anglaise. sandwich. Potercake : cake à la bière. Diner Le repas le plus important de la journée, Les boissons locales toujours plusieurs plats qu'il est de bon ton de ■ Les boissons non alcoolisées : Une eau minérale : Tipperary. faire précéder d'un verre de Sherry. ■ Les boissons alcoolisées : Bières (Guiness, Beamish, Produits Marqueurs Murphy's…), les whiskeys (Paddy, Jameson…) cidre, Baileys Fruits et Pommes, Rhubarbe et poire. Pomme de terre, et l'irish coffea. -

Iceland on the Protection of Geographical Indications for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs

24.10.2017 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 274/3 AGREEMENT between the European Union and Iceland on the protection of geographical indications for agricultural products and foodstuffs THE EUROPEAN UNION, of the one part, and ICELAND of the other part, hereinafter referred to as the ‘Parties’, CONSIDERING that the Parties agree to promote between each other a harmonious development of the geographical indications as defined in Article 22(1) of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) and to foster trade in agricultural products and foodstuffs originating in the Parties' territories, CONSIDERING that the Agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA Agreement) provides for the mutual recognition and protection of geographical indications of wines, aromatised wine products and spirit drinks, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: Article 1 Scope 1. This Agreement applies to the recognition and protection of geographical indications for agricultural products and foodstuffs other than wines, aromatised wine products and spirit drinks originating in the Parties' territories. 2. Geographical indications of a Party shall be protected by the other Party under this Agreement only if covered by the scope of the legislation referred to in Article 2. Article 2 Established geographical indications 1. Having examined the legislation of Iceland listed in Part A of Annex I, the European Union concludes that that legislation meets the elements laid down in Part B of Annex I. 2. Having examined the legislation of the European Union listed in Part A of Annex I, Iceland concludes that that legislation meets the elements laid down in Part B of Annex I. -

B AGREEMENT Between the European Community and the Swiss Confederation on Trade in Agricultural Products (OJ L 114, 30.4.2002, P

2002A4430 — EN — 31.12.2015 — 003.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B AGREEMENT between the European Community and the Swiss Confederation on trade in agricultural products (OJ L 114, 30.4.2002, p. 132) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Decision No 2/2003 of the Joint Veterinary Committee set up by the L 23 27 28.1.2004 Agreement between the European Community and the Swiss Confed eration on trade in agricultural products of 25 November 2003 ►M2 Decision No 3/2004 of the Joint Committee of 29 April 2004 L 151 125 30.4.2004 ►M3 Decision No 1/2004 of the Joint Veterinary Committee set up under the L 160 115 30.4.2004 Agreement between the European Community and the Swiss Confed eration on trade in agricultural products of 28 April 2004 ►M4 Decision No 2/2004 of the Joint Veterinary Committee set up under the L 17 1 20.1.2005 Agreement between the European Community and the Swiss Confed eration on trade in agricultural products of 9 December 2004 ►M5 Decision No 2/2005 of the Joint Committee on Agriculture set up by L 78 50 24.3.2005 the Agreement between the European Community and the Swiss Confederation on trade in agricultural products of 1 March 2005 ►M6 Decision No 1/2005 of the Joint Committee on Agriculture set up by L 131 43 25.5.2005 the Agreement between the European Community and the Swiss Confederation on trade in agricultural products of 25 February 2005 ►M7 Decision No 3/2005 of the Joint Committee on Agriculture set