Water Users Association and Irrigation Management: with Special Reference to Environmental Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. SRI. BASAVARAJ I ADDL

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. SRI. BASAVARAJ I ADDL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE BELAGAVI Cause List Date: 18-09-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 1 M.A. 8/2020 Moulasab Maktumsab Sangolli A.D. (HEARING) Age 70Yrs R/o Bailhongal Dist SHILLEDAR IA/1/2020 Belagavi. Vs The Chief officer Bailhongal Town Municipal Council Tq Bailhongal Dist Belagavi. 2 L.A.C. 607/2018 Laxman Dundappa Umarani age C B Padnad (EVIDENCE) 65 Yrs R/o Kesaral Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 3 L.A.C. 608/2018 Babalal Muktumasab Biradar C B Padanad (EVIDENCE) Patil Age 55 yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi. Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani, Tq Athani Dist Belagavi. 4 L.A.C. 609/2018 Gadigeppa Siddappa Chili age C B padanad (EVIDENCE) 65 Yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 5 L.A.C. 610/2018 Kedari Ningappa Gadyal age 45 C B Padanad (EVIDENCE) Yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 6 L.A.C. 611/2018 Smt Kallawwa alias Kedu Bhima C B padanad (EVIDENCE) Pujari Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 7 L.A.C. 612/2018 Kadappa Bhimappa Shirahatti C B Padanad (EVIDENCE) age 55 Yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani. Dist Belagavi. 1/8 Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. SRI. BASAVARAJ I ADDL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE BELAGAVI Cause List Date: 18-09-2020 Sr. -

Responsible for Plague in Bombay Province, Though They Have Been

Bull. Org. mond. Sante Bull. World Hlth Org.J 1951, 4, 75-109 SPREAD OF PLAGUE IN THE SOUTHERN AND CENTRAL DIVISIONS OF BOMBAY PROVINCE AND PLAGUE ENDEMIC CENTRES IN THE INDO-PAKISTAN SUBCONTINENT a M. SHARIF, D.Sc., Ph.D., F.N.I. Formerly Assistant Director in Charge of Department of Entomology, Haffkine Institute, Bombay b Manuscript received in September 1949 The findings of the Plague Recrudescence Inquiry in Sholapur and Adjoining Districts, conducted by Sharif & Narasimham11 12 in the districts of Sholapur and Dharwar during 1940 to 1943, do not support the idea that wild rodents help to carry plague infection from one place to another as in " temperate climes ".4 Wild rodents cannot be considered responsible for plague in Bombay Province, though they have been shown to be so in Transbaikalia, Mongolia, South-Eastern Russia, South Africa, and the western parts of the USA.17 In Bombay Province, the domestic rat perpetuates the plague infection. In some suitable places the infection among domestic rats goes on throughout the year. The infection is not apparent during the hot and dry season, its intensity being diminished because of the ill effect of prevailing climatic conditions on the wanderings of adult rat-fleas ; it pursues the course of a slow subterranean enzootic from burrow to burrow. The conclusion of the off-season is characterized by the advent of the rainy season, which exerts its influence in two ways first, it causes the rats from outside shelters to herd into burrows indoors and remain there perforce, which results in a considerable increase in the rat population within houses; secondly, it brings down the temperature and increases the humidity to such an extent as to result in a striking rise in the flea population and to allow rat-fleas to come out of burrows to attack human beings. -

Non-Teaching Staff and Nursing Staff

SL.NO NAME OF THE STAFF DESIGNATION 1 MRS. D. M. KHADABADI Nursing Suprintendent 2 SHIVALEELA F YARAZARVI Nursing Suprintendent 3 Mr. Veereshkumar S. Nandgoan Nursing Suprintendent 4 Mr. Ashok M. Kamat Nursing Suprintendent 5 Mr. Gururaj R Udapi Nursing Suprintendent 6 Mr. Gavisiddhayya B. Salimath Nursing Suprintendent 7 Mr. Mahaling M. Hulagabali Nursing Suprintendent 8 Mr. Honnagouda I Patil Nursing Suprintendent 9 Mr. Vikrant S Nesari Nursing Suprintendent 10 Mr. Manjunath M. Sogalad Nursing Suprintendent 11 Mrs. Asha V. Bhat Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 12 Mrs. Shubharani S. Muragod Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 13 Mrs. Nirmala D’souza Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 14 Mrs. Namrata M. Devulkar Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 15 Mr. Jagadeesh G.Hubballi Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 16 Mrs. Uma L.Kole Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 17 Mr. Amey M. Khande Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 18 Mrs. Sushma B Patil Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 19 Mrs. Vaishali S. Bagewadi Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 20 Mr. Umesh M. Nandgoan Dept.Nursing Suprintendent 21 MR. ANILKUMAR. B. BIRADAR Assistant Nursing Superintendent 22 MR. ANNARAO. M. DESAI Assistant Nursing Superintendent 23 MR. PRAVEEN. G. DYAPUR Assistant Nursing Superintendent 24 MRS. MARIAMMA BIBIN BABYDASAN Assistant Nursing Superintendent 25 MS. SARITA. U. NAIK Assistant Nursing Superintendent 26 MR. CHANDRAKANT. D. MORE Assistant Nursing Superintendent 27 RENUKA RAMESHBABU Asst Nursing Suprintendent 28 SHAKUNTALA CHANDRAKANT KORE Asst Nursing Suprintendent 29 SILVY RAMESH MUDHOL Asst Nursing Suprintendent 30 BALABEI -

District Census Handbook, Belgaum, Part XII-B, Series-11

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 Series ·11 KARNATAKA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK BELGAUM DISTIUCf PART XII·B VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT SOBHA NAMBISAN Director or Census Operations, Kamataka CONTENTS • ..ge No. FOREWORD v - vi PREFACE vii-viii IMPORTA..W STATISTICS ix - xii ANALYTICAL NOTE 1 - 37 Explanatory Notes 41 - 44 A. District Primary Census Abstract 46-63 (i) Village/l'own~ Primary Census Abstract Alphabetical List of Villages - Athni C.D.Block 67 - 69 Primary CeQ$us Abstract - Athni C.D.Block 70 - 81 Alphabetical Lis1 of Villages - Belgaum C.D.Block 85-88 Primary Census Abstract - Belgaum C.D.Block 90 - 109 Alphabetical List of Villages - Chikodi CD.Block 113 - 115 P~ Census Abstract - Chikodi C.D.Block 116 - 131 Alphabetical List of Villages - Gokak C.D.Block 135 - 137 Primary Census Abstract - Gokak C.D.Block 138 - 153 Alphabetical List of Villages - Hukeri C.D.Block 157 - 160 Primary Census Abstract - Hukeri C.D.Block 162 - In Alphabetical List of Villages - Kbanapur C.D.Block 181 - 186 Primary Census Abstract - .Kbanapur C.D.Block 188 - 215 Alphabetical List of Villages - Parasgad C.D.Block· 219 - 221 Primary Census Abstract - Parasgad C.D.Block 222 - 237 : . Alphabetical List P~ Villages - R.ybag C.D.Block 241 - 242 Primary CensUs Abstract - Raybag C.D.Block 244 - 251 Alphabetical List of Villages - Ramdurg C.D.Block 255 - 257 Primary Ceqsus Abstract - Ramdurg C.D.Block 258 - 273 i Alphabetical List oLVillages - Sampgaon CD:Block m - '1PIJ Primary Census Abstract -- Sampgaon C.D.Block m - '1!:1T (iii) Page No. (ii) Town Primary Census Abstract (Wardwise) Alphabetic:al List of Towns in the District 301 Athni 302 - 305 Bailhoagal 302 - 303 Chikodi 302 - 305 Dhupdal 302 - 305 Gobk 302 - 305 , Gokak FaDs (NAC) 306 - 309 . -

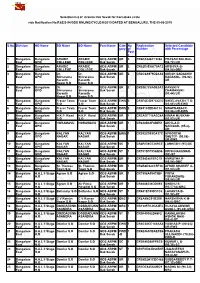

Selection List of Gramin Dak Sevak for Karnataka Circle Vide Notification No.R&E/2-94/GDS ONLINE/CYCLE-II/2019 DATED at BENGALURU, the 05-08-2019

Selection list of Gramin Dak Sevak for Karnataka circle vide Notification No.R&E/2-94/GDS ONLINE/CYCLE-II/2019 DATED AT BENGALURU, THE 05-08-2019 S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ UR 2 CR4FA844C73286 PRASAD BALIKAI- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (94.72)-UR 2 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ UR 2 CR02E8EAA79A72 ARSHIYA G- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (94.08)-OBC 3 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ UR 2 CR0C2A979D2A34 GIRISH SADASHIV East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak KADAKOL- (93.92)- Karanth Karanth UR Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 4 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ UR 2 CR02E7C8A9E2A2 KAVERI V East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak CHAMAKERI- Karanth Karanth (93.44)-UR Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 5 Bangalore Bangalore Fraser Town Fraser Town GDS ABPM/ EWS 2 CR5F6C4297CCE5 SHEELAVATHI T S- East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak (83.68)-UR-EWS 6 Bangalore Bangalore Fraser Town Fraser Town GDS ABPM/ EWS 2 CR65143ED46114 SWAPNABAI R- East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak (80.96)-UR-EWS 7 Bangalore Bangalore H.K.P. Road H.K.P. Road GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR2AD7718A2C4A AIMAN MUSKAN- East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak (93.92)-UR 8 Bangalore Bangalore HORAMAVU HORAMAVU GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR248D61F6BE51 AKHILA D East GPO Dak Sevak NADIGAR- (95.2)- UR 9 Bangalore Bangalore KALYAN KALYAN GDS ABPM/ EWS 1 CR352C953CA17C SPOORTHI East GPO NAGAR NAGAR Dak Sevak SHETTY- (90.08)- UR-EWS 10 Bangalore Bangalore KALYAN KALYAN GDS ABPM/ SC 1 CR4F838CE269CE LANKESH- (95)-SC East GPO NAGAR NAGAR Dak Sevak 11 Bangalore Bangalore KALYAN KALYAN GDS ABPM/ ST 1 CR331D5793AB56 KRISHNAKUMAR- East GPO NAGAR NAGAR Dak Sevak (92)-ST 12 Bangalore Bangalore KALYAN KALYAN GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR2942461B1C19 AMRUTHA R- East GPO NAGAR NAGAR Dak Sevak (95.04)-OBC 13 Bangalore Bangalore St. -

Downloaded from the Server for Offline Analysis

Final Report for the Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program Volume 2: The Appendices LIST OF APPENDICES APPENDIX 1: DESIGN AND MONITORING FRAMEWORK ................................................................ 1‐4 APPENDIX 2: KISWRMIP IWRM ROADMAP .................................................................................. 5‐11 APPENDIX 3: WATER GOVERNANCE .......................................................................................... 12‐38 APPENDIX 4A: OUTPUT 1 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ...................................................... 39‐96 APPENDIX 4B‐1: OUTPUT 2 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (MANAGEMENT OF IRRIGATION SUB PROJECTS IS MODERNIZED) ................... 97‐122 APPENDIX 4B‐2: OUTPUT 2 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (WUCS AND AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT) .................................................... 123‐134 APPENDIX 4C: OUTPUT 3 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PLAN .................................................. 135‐148 APPENDIX 5: TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR WUCS SUPPORT SERVICE TEAM (SST) ................. 149‐153 APPENDIX 6: IWRM CAPACITY ASSESSMENT .......................................................................... 154‐187 APPENDIX 7: PROCUREMENT CAPACITY ASSESSMENT .......................................................... 188‐202 APPENDIX 8: STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION & CONSULTATION ........................................... 203‐214 APPENDIX 9: COMMUNICATIONS STRATEGY ......................................................................... 215‐220 APPENDIX -

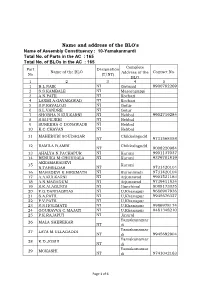

Name and Address of the BLO's Name of Assembly Constituency : 10-Yamakanmardi Total No

Name and address of the BLO's Name of Assembly Constituency : 10-Yamakanmardi Total No. of Parts in the AC : 165 Total No. of BLOs in the AC : 165 Complete Part Designation Name of the BLO Address of the Contact No. No (T/NT) BLO 1 2 3 4 5 1 B.L.NAIK NT Gavanal 9900782269 2 S.S.KAMBALE NT Masaraguppi 3 A.N.PATIL NT Kochari 4 LAXMI A.GAYAKAWAD NT Kochari 5 S.P.RAVALOJI NT Gotur 6 S.L.VANDRE NT Gotur 7 SHOBHA N.KULKARNI NT Hebbal 9902719284 8 S.M.PUJERI NT Hebbal 9 SUREKHA G.DONAWADE NT Hebbal 10 K.C.CHAVAN NT Hebbal 11 MAHEBUBI SOUDAGAR Chikkalagudd NT 9731568558 12 RAMILA B.AMBI Chikkalagudd NT 9008220984 13 AHALYA N.PACHAPUR NT Kurani 9901137037 14 RENUKA M.CHOUGALA NT Kurani 9379701819 AKKAMAHADEVI 15 Kurani N.TAHSILDAR NT 9731420104 16 MAHADEVI K.HIREMATH NT Kuraniwadi 9731420104 17 A.A.KULKARNI NT Arjunawad 9901521163 18 A.N.MAGADUM NT Arjunawad 9739411834 19 S.K.ALAGUNDI NT Hanchinal 8088173035 20 P.G.DANDAGIDAS NT U,Khanapur 9686907936 21 S.A.PATIL NT U,Khanapur 9945676327 22 P.V.PATIL NT U,Khanapur 23 S.S.HOLIMATH NT U,Khanapur 9986978174 24 GOURAVVA C.MAJATI NT U,Khanapur 9481348210 25 P.K.RAJAPUT NT Jinaral Yamakanamar 26 MALA SHEREKAR NT di Yamakanamar 27 LATA M.ULLAGADDI NT di 9945692904 Yamakanamar 28 K.D.JOSHI NT di Yamakanamar 29 MOKASHI NT di 9741042163 Page 1 of 6 Complete Part Designation Name of the BLO Address of the Contact No. -

Yemkanmardi.Pdf

MLA Constituency Name Mon Aug 24 2015 Yemkanmardi Elected Representative :Jarakiholi Satish Laxmanarao Political Affiliation :Indian National Congress Number of Government Schools in Report :170 KARNATAKA LEARNING PARTNERSHIP This report is published by Karnataka Learning Partnership to provide Elected Representatives of Assembly and Parliamentary constituencies information on the state of toilets, drinking water and libraries in Government Primary Schools. e c r s u k o o S t o r e l e B i t o a h t t t T e i e W l l i n i W g o o o y y n T T i r r m k s a a s r r l m y n r i b b i o o r i i District Block Cluster School Name Dise Code C B G L L D BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KHPS BHOMANAHATTI HALBHAVI 29010404402 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KHPS BHUTARAMANAHATTI 29010402001 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KHPS HOSA VANTAMURI 29010405101 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KHPS SUTAGATTI 29010410901 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KLPS CHEKPOST SUTAGATTI 29010410902 Others SUTAGATTI BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KLPS GHUGRENHATTI 29010413101 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KLPS GODIHAL 29010403801 Well BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KLPS GURAMATTI KATTANBHAVI 29010405903 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI KLPS RAMADURG HALBHAVI 29010404405 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI M.H.P.S GUGRYANATTI BAMBARGE 29010401303 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. BHUTARAMATTI UHPS HOSA VANTAMURI 29010405102 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. HANDIGNUR KHPS BODAKENAHATTI 29010402702 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. HANDIGNUR KHPS HOSAIDDALHOND NINGYANATTI.(K) 29010409302 Others BELGAUM BELGAUM RURAL. -

District :: 01, Belgaum (South) Taluk :: 01, Ramadurg

District :: 01, Belgaum (south) Taluk :: 01, Ramadurg GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA (DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION) OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR PUBLIC INSTRUCTION CENTRALISED ADMISSION CELL FOR B.ED AND D.ED ADMISSIONS, K.G. ROAD, BANGALORE-02 FINAL LIST OF CANDIDATES SELECTED FOR ADMISSION TO ADARSHA VIDYALAYAS FOR THE YEAR 2016 - 2017 CAC, Computer Section 1> District Code/Name :: 01, Belgaum (south) Taluk Code/Name :: 01, Ramadurg Page No : 1 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Slno RegNum Candidate Name Sex Rur/Urb PhyHan DateOfBirth Group Medium Marks Selected ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. 1601010502 POORNIMA MUSAGANNI Female Rural No 04/04/2005 2A KANNADA 94 GM_OT_WM 2. 1601010809 SHIVPRASAD DODAMANI Male Rural No 05/07/2005 ST KANNADA 91 GM_OT_KAN 3. 1601010836 RAKSHITA DUGGANI Female Rural No 03/05/2005 2A KANNADA 90 GM_OT_WM 4. 1601011060 ISHWARYA SUNAGAR Female Rural No 23/05/2005 C1 KANNADA 90 GM_OT_WM 5. 1601010274 DEEPTI DEVATAGI Female Rural Yes 04/06/2005 GM KANNADA 89 GM_OT_WM 6. 1601010483 IRANNA DYAMANGOUDRA Male Rural No 30/06/2005 3B KANNADA 89 GM_OT_KAN 7. 1601010292 VINAYAK HAGEDAL Male Rural No 05/08/2005 2A KANNADA 89 GM_OT 8. 1601010876 MANJUNATH LATTI Male Rural No 15/04/2004 3B KANNADA 88 GM_OT 9. 1601010484 UDAY GONDKAR Male Rural No 28/01/2005 2A KANNADA 88 GM_OT 10. 1601010359 GOURISH HARAVI Male Rural No 07/03/2005 2A KANNADA 88 GM_OT 11. 1601011169 SHYAMALA NAYKAR Female Rural No 15/03/2005 2A KANNADA 88 GM_OT_WM 12. 1601010509 SATLINGAYYA GUNAYYANAVA Male Rural No 04/05/2005 3B KANNADA 88 GM_OT 13. 1601010002 SRUSHTI Female Rural No 12/07/2006 GM KANNADA 88 GM_OT_WM 14. -

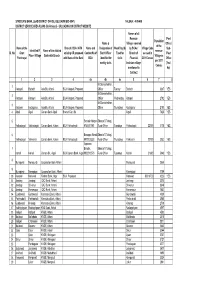

Sl. No. Name of the Gram Panchayat Identified FI Place / Village Name Of

SYNDICATE BANK, LEAD DISTRICT OFFICE, BELGAUM (BIC-0541) TALUKA :- ATHANI DISTRICT SERVICE AREA PLANS (Re-Revised) - UPLOADING ON DISTRICT WEBSITE Names of all Revenue Post Population Name & Villages covered Office / of the Name of the Branch / BCA / ATM Name and Designation of Week Day (S) by BCAs / Village Code Sub- Identified FI Name of the allotted revenue Sl. No. Gram existing OR proposed Contact No.of Bank Officer Fixed for Branch of as used in Post Place / Village Bank with Branch Village as Panchayat with Name of the Bank BCA identified for visits Financial 2011 Census Office per 2001 weekly visits Inclusion villages (Yes / Census mentioned in No) Col.No.2 1 2 3 4 4a 4b 4c 5 6 7 8 Mr.Somashekhar, 1 Katageri Badachi Axis Bk, Athani BCA Katageri, Proposed Officer Tueday Badachi 3387 YES Mr.Somashekhar, 2 Katageri Katageri Axis Bk, Athani BCA Katageri, Proposed Officer Wednesday Katageri 2792 YES Mr.Somashekhar, 3 Katageri Kodaganur Axis Bk, Athani BCA Katageri, Proposed Officer Thursdays Kodaganur 2193 YES 4 Aigali Aigali Canara Bank Aigali Branch Can. Bk. Aigali 7425 YES 5 Santosh Magar Shweta S Totagi, Yalihadagali Yalihadagali Canara Bank, Athani BCA Yalihadagali 9740411581 Rural Officer Tuesdays Yalihadagali 22000 3178 YES 6 Basappa Kiwadi Shweta S Totagi, Yalihadagali Yakkanchi Canara Bank, Athani BCA Yalihadagali 9972025353 Rural Officer Thursdays Yakkanchi 22100 2052 YES Appanna 7 Biradar, Shweta S Totagi, Kohalli Kohalli Canara Bk., Aigali BCA Canara Bank, Aigali 9902013573 Rural Officer Tuesdays Kohalli 21600 5948 YES 8 -

Sl. No. Roll No Name Mobile Category VH PH Subject` REF 1 15020128 JAGADESHA D 9739499799 CAT-IIIB NO NO KANNADA DU79675533 2 15

Sl. No. Roll No Name Mobile Category VH PH Subject` REF 1 15020128 JAGADESHA D 9739499799 CAT-IIIB NO NO KANNADA DU79675533 2 15030001 LAMBODAR CHANDRAKANT GAONKAR 7259980627 CAT-IIA NO NO ECONOMICS DU79186494 3 15010138 ANAND BASARAGI 8147087505 CAT-IIA NO NO COMMERCE DU79552467 4 15060002 NAGRAJ SAHDEV BELGAONKAR 9742436236 CAT-IIIB NO NO HISTORY DU79136956 5 15030007 CHEERANJEEVI KANNER 9916972682 ST NO NO ECONOMICS DU79077380 6 15020005 RAVI DEEVIGIHALLI 9845383596 ST NO NO KANNADA DU79078684 7 15090116 SOMANAT PUJAR 7829613973 SC NO NO HINDI DU79654339 8 15070031 SANTOSH KARAMALLAVAR 9916658271 CAT-IIIB NO YES SOCIOLOGY DU79526118 9 15040188 BASAVARAJ NAGALINGAPPA MALAGIHAL 9148928679 CAT-IIIB NO NO ENGLISH DU79759293 10 15250009 RAGHAVENDRA K SALI 9480774670 ST NO NO PHYSICAL SCIENCE DU79005835 11 15200122 DEMAPPA GOUDARA 7353466364 CAT-I NO NO PHYSICAL EDUCATION DU79802106 12 15380002 KOLI SHIVANAND HIRAGAPPA 9448627782 CAT-I NO NO Linguistics DU79208258 13 15040004 PARINITHA P 8277902771 CAT-IIIA NO NO English DU79052965 14 15010029 NAVEEN 9886881188 CAT-IIIA NO NO ACCOUNTING & TAXATION COMMERCE DU79082737 15 15050094 NAVEEN MARIGOUDAR 7259231516 CAT-IIIB NO NO POLITICAL SCIENCE DU79051286 16 15040632 PRAVEEN KURABAR S 8095102476 CAT-IIA NO NO ENGLISH DU80174218 17 15050002 ASHOK MADABHAVI 8105859120 CAT-IIA NO NO POLITICAL SCIENCE DU79074451 18 15280015 HATPAKKI APARNA JAYARAJ 9886907470 CAT-IIA NO NO BIOCHEMISTRY DU79006523 19 15270012 NIRANJANSWAMI SANGAYYA HIREMATH 8095703203 GEN NO NO CHEMISTRY DU79139002 20 15240006 SHRIDHAR -

Government of Karnataka Provisional Habitation Wise Neighbourhood

Government of Karnataka O/o Commissioner for Public Instruction, Nrupatunga Road, Bangalore - 560001 RURAL Provisional Habitation wise Neighbourhood Schools - 2016 ( RURAL ) Habitation Name School Code Management Lowest Highest Entry type class class class Habitation code / Ward code School Name Medium Sl.No. District : Chikkodi Block : ATHANI Habitation : MOTAGI TOT---29300100128 29300100128 29300100101 Govt. 1 8 Class 1 MOTAGI TOT Govt Kannada Higher Primary School MOTAGI TOT 05 - Kannada 1 Habitation : SHANTI NAGAR CHIKKATTI---29300100130 29300100130 29300100103 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 SHANTI NAGAR CHIKKATTI Govt Kannada Lower Primary School SHANTI NAGAR ATHANI 05 - Kannada 2 WARD NO 21 Habitation : SHIVAYOGI NAGAR---29300100131 29300100131 29300100104 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 SHIVAYOGI NAGAR Govt Urdu Lower Primary School SHIVAYOGI NAGAR ATHANI 18 - Urdu 3 WARD NO 22 Habitation : SHIVAYOGI TOT---29300100132 29300100132 29300100105 Govt. 1 6 Class 1 SHIVAYOGI TOT Govt Kannada Higher Primary School SHIVAYOGI TOT WARD 05 - Kannada 4 NO 23 Habitation : HOSATTI---29300100133 29300100133 29300100106 Govt. 1 7 Class 1 HOSATTI Govt Kannada Higher Primary School HOSATTI 05 - Kannada 5 Habitation : MAHANTESH NAGAR---29300100134 29300100134 29300100107 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 MAHANTESH NAGAR Govt Kannada Lower Primary School MAHANTESH NAGAR 05 - Kannada 6 Habitation : SANKONATTI---29300100136 29300100136 29300109119 Govt. 1 8 Class 1 SANKONATTI Govt Kannada Higher Primary School SANKONAHATTI 05 - Kannada 7 Habitation : WADRATTI---29300100137 29300100137 29300100112 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 WADRATTI Govt Kannada Lower Primary School WADRATTI 05 - Kannada 8 Habitation : HANAMAPURE TOT HOSATTI---29300100138 29300100138 29300100114 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 HANAMAPURE TOT HOSATTI Govt Kannada Lower Primary School HANMAPURE TOT 05 - Kannada 9 Habitation : ATHANI (RURAL)---29300100140 29300100140 29300100111 Pvt Unaided 1 5 Class 1 ATHANI (RURAL) SHRI SADGURU SAMARTH AVAJEEKAR MAHARAJAR K L 05 - Kannada 10 P S ATHANI RURAL Habitation : LOKUR TOT---29300100201 29300100201 29300100203 Govt.