Chapter - V Chapter -V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER-S EMERGENCE and EVOLUTION of SIKKIM DEMOCRATIC FRONT AS a POLITICAL PARTY CHAPTER 5 Emergence and Evolution of Sikkim Democratic Front As a Political Party

CHAPTER-S EMERGENCE AND EVOLUTION OF SIKKIM DEMOCRATIC FRONT AS A POLITICAL PARTY CHAPTER 5 Emergence and Evolution of Sikkim Democratic Front as a Political Party 1. Dissention within Sikkim Sangram Parishad It has already been discussed in the last part of the previous chapter about the feud between Chamling and Bhandari and the former's expulsion from the party on the ground of ideological differences. In this chapter, we will try to assess the reason behind the dissention and the emergence of a new state political outfit, Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) and its role in the state politics. Pawan Chamling, a son of a farmer from Yangang, south Sikkim had first started his political career as the President of his village Yangang Gram Panchayat Unit in 1982 and became an MLA of Damthang Constituency in 1985. He slowly climbed up the political ladder to become a Cabinet Minister in SSP Government in 1989 and was the Minister- in-charge for Industries, Printing and Information & Public Relations. (Commemorative issue:25 years of Statehood) On his days as the SSP minister for two and half years, there started growing a discord on principles and practices of politics between him and the then Chief Minister Nar Bahadur Bhandari. The differences between him and the leadership of the SSP were neither petty nor personal. There were substantial differences on issues of principle and ideology. (B B Gurung) 2012) (Bali) 2003) It was alleged that during Bhandari's rule, he ruled as a monarch without a crown. The fundamental rights of speech and expression granted by the constitution to its citizens became CHAPTER 5 : Emergence and Evolution of Sikkim Democratic Front as a Political Party imprisoned within the bounds of Mintokgang. -

Profile of Chaman Lal Gadoo

PROFILE OF CHAMAN LAL GADOO (AUTHOR AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST) VIDYA GAURI GADOO RESEARCH CENTRE S-71, Sunder Block, Shakarpur, Delhi—110092, Mob.9891297912, Email: [email protected] , Blog: www.clgadoo.blogspot.com Chaman Lal Gadoo with Swami Ramdev 1 PROFILE IN PICTURES C.L.Gadoo, President Smt. PRATIBHA PATIL & President Sh. K.R.NARAYANAN C.L.Gadoo with PM Sh.A.B.Vajpayee, & Sh. Madan Lal Khurana, BJP Delhi chief C.L.Gadoo with Dy. PM Sh.L.K.Advani & with Sh.L.K.Advani and Sh.K.N Sahani, 2 SWAMI SRI SRI RAVISHANKAR RELEASING BOOK KASHMIR HINDU SHRINES SWAMI RAMDEV RELEASING THE BOOK—KASHMIR HINDU SHRINES Author with Swami Girijeshananda(Jammu)Author with Acharya Balkrishna(Haridwar) 3 CL.Gadoo with PM Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru & with PM Sh.P.V.Narasimha Rao C.L. Gadoo, Sh. A.B.Vajpayee, Sh.S.L.Shakdhar, Dr.Hari Ohm, Dr. M. K.Teng c.l.gadoo,Sh.M.L.Khurana,Sh.B.S.Shekhawat,Sh.S.L.Shakdhar,Sh.KeshoBhaiPatel 4 BRIEF PROFILE Chaman Lal Gadoo, born in the year 1937 at Srinagar, Kashmir has been ardent Hindu nationalist from an early age. His father Pandit Janki Nath Gadoo, a teacher by profession, was a highly learned Kashmiri Pandit and his Mother Smt. Ragniya Gadoo, was a noble house wife, with a spiritual and religious discipline, and social bonding. She left for heavenly abode, at an early age. His Wife Smt. Vidya Gauri Gadoo was organizing & training commissioner, Bharat Scouts and Guides, Delhi State. Chaman Lal completed his early education at Srinagar and received technical education in Electronics Engineering and Industrial management at Delhi. -

P.S. Golay Becomes CM of Sikkim

P.S. Golay becomes CM of Sikkim News The Sikkim Krantikari Morcha (SKM) president Prem Singh Tamang, popularly known as PS Golay, took oath as the new Chief Minister of Sikkim on Monday. More in News ● In the recently concluded Sikkim Assembly elections, Sikkim Krantikari Morcha (SKM), had beaten the Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) and dethroned Pawan Kumar Chamling, the longest-serving Chief Minister of the country. PK chamling served for five consecutive terms since 1993. ● The SKM, founded in 2013, won a slender majority in the 32-member Sikkim legislative assembly (Lowest number of seats) by bagging 17 seats against the 15 won by the SDF. The party is also an ally of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at the Centre and thus a part of the National Democratic Alliance. ● However, Tamang did not contest the election to focus on the party’s campaign. Article 164 of the Indian Constitution which allows anyone to become a minister or a chief minister provided he got himself elected to the Assembly within six months of taking the oath. About Sikkim ● Sikkim is situated at the North East of the union. Sikkim became the 22nd State of India Vide Constitution (36th Amendment) Act 1975. ● In 1950 the kingdom became a protectorate of the Government of India vested with autonomy in its internal affairs while its defence, communications and external relation under the responsibility of the protector. ● The kingdom finally opted to become full-fledged State of the Indian Union with effect from 26 April, 1975 vide the Constitution 36th Amendment Act 1975 with special provision laid for the State under article 371(F) of the Constitution of India. -

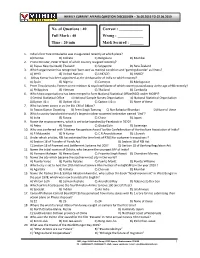

No. of Questions : 40 Full Mark : 40 Time : 20 Min Correct : ___

WEEKLY CURRENT AFFAIRS QUESTION DISCUSSION – 26.05.2019 TO 02.06.2019 No. of Questions : 40 Correct : ____________ Full Mark : 40 Wrong : _____________ Time : 20 min Mark Secured : _______ 1. India’s first Tree Ambulance was inaugurated recently at which place? A)Chennai B) Kolkata C) Bengaluru D) Mumbai 2. Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill of which country resigned recently? A) Papua New Guinea B) Thailand C) Singapore D) New Zealand 3. Which organization has recognized ‘burn-out’ as medical condition and ‘gaming disorder’ as illness? A) WHO B) United Nations C) UNESCO D) UNICEF 4. Abhay Kumar has been appointed as the Ambassador of India to which country? A) Spain B) Nigeria C) Comoros D) Madagascar 5. Prem Tinsulanonda, Former prime minister & royal confidante of which country passed away at the age of 98 recently? A) Philippines B) Vietnam C) Thailand D) Cambodia 6. Which two organisations has been merged to form National Statistical Office(NSO) under MOSPI? i) Central Statistical Office ii) National Sample Survey Organisation iii) National Statistical Organisation A)Option i & ii B) Option i & iii C) Option ii & iii D) None of these 7. Who has been sworn in as the 6th CM of Sikkim? A) Pawan Kumar Chamling B) Prem Singh Tamang C) Nar Bahadur Bhandari D) None of these 8. Which country launched the world’s largest nuclear-powered icebreaker named ‘Ural’? A) India B) Russia C) China D) Japan 9. Name the cryptocurrency, which is set to be launched by Facebook in 2020? A) Petro B) Bitcoin C) GlobalCoin D) Sovereign 10. -

Official Gazette Government of Goa, Daman and Diu

I BEGD. GOA-I! I Panaji, 17th July, 1980 IAsadha 26, 1902) SERIES I No. 16 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA. DAMAN Banking companies and also in respect ,of the instru meuts of reconveyance executed by the Banking AND DIU companies in favour of such farmers and/or their guarantors. Department of Personnel and Administrative Reforms By order and in name of the Lieutenant Governor of Goa, Daman and Diu. Notification A. P. Panvelkar, Under Secretary (Finance). 24/&/SO-PER Panaji, 7th July, 1980. In exercise of the powers vested in him under rule 4 of "Goa, Daman and Diu Police Service Rules 1973" , ... the Administrator of Goa, Daman and Diu is pleased to declare the following posts created vide order No. Law Department (Legal Advice) HD(G)3-4-16-78 dated 31-5-1980 of Home Depart ment (General) as 'duty posts' of the said service Notification for the purpose of recruitment thereto until further orders. LD/Acts/1980(6) DY. Superintendent of Police ...... Five posts. The following Central Acts namely:- 1. The Central Excises and Salt and Additional By order and in the name' of the Administrator Duties of Excise (Amendment) Act, 1980. 2. The of Goa, Daman and Diu. Representation of the People (Amendment), Act, 1980. 3. The Appropriation (Vote on Account) Act, G. H. Mascarenha.s, Under Secretary (Personnel) 1980. 4. The Appropriation (No.2) Act, 1980. '5. The Panaji, 7th July, 1980. Finance Act, 1980. 6. The Union Duties of Excise (Electricity) Distribution Act, 1980. 7. The Constitu tion (Forty fifth Amendment) Act, 1980 which were .. -

CHAPTER-4 STATE PARTY DOMINANCE: CASE of SIKKIM SANGRAM PARIS HAD CHAPTER 4 State Party Dominance: Case of Sikkim Sangram Parishad

CHAPTER-4 STATE PARTY DOMINANCE: CASE OF SIKKIM SANGRAM PARIS HAD CHAPTER 4 State Party Dominance: Case of Sikkim Sangram Parishad 1. Merger of Sikkim Janata Parishad Immediately after the assumption of office on 18/10/1979, Bhandari found Sikkim politically, economically and socially backward. There was no planning process for rapid development of Sikkim and there was no communal harmony. His government first took steps to meet the basic needs of the general public and refurbished the entire administrative set up in accordance with the change needed (Nar Bahadur Bhandari, 2011). The Parliamentary election took place in Sikkim on the 3rd January, 1980. It was the first such election in Sikkim. In 1977 there was no election, since the candidate was returned uncontested. The bye-election to Sikkim Legislative Assembly (SLA) for Khamdong and Chakung was also held along with Sikkim Parliamentary constituency election in 1980. (Sengupta N. , State Government and Politics: Sikkim. , 1985, p. 113) Sikkim J anata Parishad won all the seats and at the centre, Congress (I) returned to power with overwhelming majority. (ECI, Statistical Report on the Elections to the Lok Sabha, 1980) Politics in Sikkim assumed an interesting shape after the change in leadership at the centre. All the major political parties were in the rat race over the issue of getting recognition of the Congress (!).Whereas the opposition parties- SPC, a section of SCR as well as Janata Party wanted to join hands and come to power by getting support of Congress(I).The ruling party, SJP wanted Centre's CHAPTER 4 : State Party Dominance : Case of Sikkim Sang ram Parishad recognition to secure its power position and ultimately it was recognized by the Central leadership in July 1981.Thus shedding its 'separate identity of State Party' the SJP merged itself with the Congress (I) (Sengupta N. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

Record Keeper

1 ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES TO APPEAR IN THE EXAMINATION FOR THE POST OF RECORD KEEPER Sl. No. Name of the applicant & Address 1. Mr. Yuvaraj Gurung S/o Mani Kumar Gurung R/o Dovan, Perbing, South Sikkim 2. Ms. Mangal Maya Limboo D/o Mr. Budhi Raj Limboo R/o Mangshila, North Sikkim 3. Mr. Benjamin Subba S/o Mr. Ajit Subba R/o Development Area, Gangtok, East Sikkim 4. Ms. Romela Lepcha D/o Mr. Tshering Lepcha R/o Chujachen, Rongli, East Sikkim 5. Ms. Rekha Gurung W/o Mr. Prakash Gurung R/o Deythang, Rinchenpong, West Sikkm A/p Deorali School Road, Gangtok, East Sikkim 6. Mr. Zigmee Topzer Sherpa S/o Mr. Passang Lhendup Sherpa R/o Upper Phalidara, Namchi, South Sikkim 7. Mr. Sandeep Pradhan S/o Mr. Aita Kr. Pradhan R/o Tadong College Valley, Gangtok, East Sikkim 8. Mr. Phurba Tshewang Bhutia S/o Mr. Tempo Bhutia R/o Deorali Bazar, Gangtok, East Sikkim 9. Mr. Lijen Manger S/o Mr. Nar Bahadur Manger R/o Melli, South Sikkim 10. Ms. Sonam Ongmu Lachungpa (Bhutia) D/o Lt. Phurbo Thendup Bhutia R/o Lachung, North Sikkim A/p Deorali School Road, Gangtok, East Sikkim 2 11. Mr. Amosh Kiran Rai S/o Mr. Prakash Rai R/o Namli, behind Smile Land Ranipool, East Sikkim 12. Mr. Abinash Shrestha S/o Mr. Rup Narayan Pradhan R/o Bardang, Singtam, East Sikkim 13. Ms. Shrada Bhujel D/o Mr. Subash Bhujel R/o Namphing GPU, Pabong, South Sikkim 14. Mr. Tenzing Dichen Dorjee S/o Lt. Nim Tshering Bhutia R/o Upper Syari, Gangtok 15. -

Chapter - Vi Chapter - Vi

CHAPTER - VI CHAPTER - VI 6.1 THE POLITICS OF KAZI LHENDUP DORJEE KHANGSARPA (1974- 1979) While the father of the nation is Mahatma Gandhi, the father of nascent democracy in Sikkim is Kazi Lhendup Dorjee Khangsarpa or Kazi Saheb - a pioneer, visionary with Political enlightenment and maturity is one of those who make a difference. Kazi Lhendup Dorjee Khangsarpa was born in the year 1904 at Pakyong, East Sikkim, while Col. Younghusband led the British Mission to Tibet and changed the course of History of Sikkim. In fact, in his childhood, Kazi Lhendup Dorjee Khangsarpa entered the spiritual life i.e., when he was 6 years old. He was educated as a monk (Lama - Buddhabikshu) at Rumtek Monastery of East Sikkim, situated very near to capital Gangtok. He was a disciple and student of his own uncle Tshufuk Lama Rabdon Dorji - the Head Lama of Rumtek Monastery. The then Maharaja o f Sikkim, Sikyong Tulku - during his visit to Rumtek Monastery showed a great liking and was attracted by the cute and young monk Lhendup, took him to Gangtok and put him in a Tibetan School. In his 16^*’ year Lhendup Dorjee returned to Rumtek Monastery to undergo two years rigorous training in Lamaism of Mahayana-Buddhism (Lamaism is a combination of both Tantrayana and Mantrayana). Finally, he succeeded in his teen age to Lama Ugen Tenzing to preach as Head Lama of Rumtek Monastery for about eight years. Leaving monastic life young Kazi had joined ‘Young Men’s Buddhist Association’ founded by his brother Kazi Phag Tshering in Darjeeling. -

Sub-National Jurisdictional Redd+ Program for Sikkim, India

SUB-NATIONAL JURISDICTIONAL REDD+ PROGRAM FOR SIKKIM, INDIA Prepared by Sikkim Forest, Environment & Wildlife Management Department Supported by the USAID-funded Partnership for Land Use Science (Forest-PLUS) Program June 2017 Version 1.2 Sub-National Jurisdictional REDD+ Program for Sikkim, India 4.1 Table of Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 9 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 12 1.1 Background and overview..................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Objective ..................................................................................................................................... 17 1.3 Project Executing Entity .............................................................................................................. 18 2. Scope of the Program .................................................................................................................. -

Ethnic Politics and Democracy in the Eastern Himalaya | 205

ETHNIC POLITICS AND DEMOCRACY IN THE EASTERN HIMALAYA | 205 INTERPRETING DEMOCRACY: ETHNIC POLITICS AND DEMOCRACY IN THE EASTERN HIMALAYA Mona Chettri Introduction The surge of cultural revivalism, demands for ethnic homelands and affirmative action policies based on ethnic affiliation evince the establishment of ethnic identity based politics in the eastern Himalayan borderland where most political contestations are now made on the basis of ethnic claims (see Caplan 1970; Subba 1992, 1999; Sinha 2006, 2009; Hangen 2007, 2010; Vandenhelsken 2011). Ethnicity and ethnic identity may have emerged recently as conceptual categories, but they have always formed an intrinsic component of the lived experiences, history, politics and culture of the region and what contemporary politics particularly highlights is the malleability with which ethnic identity can adapt itself to changing political environments. Ethnic identity is understood as a synthesis of ascribed traits combined with social inputs like ancestral myths, beliefs, religion and language, which makes ethnicity partly ascribed and partly volitional (Joireman 2003). It is socially constructed, subjective and loaded with connotations of ethnocentrism which can be detrimental for modern state building. If subjective criteria determine ethnic group formation and politics, democracy provides a wider base of socio-political collectivity that goes beyond kinship, religion, language etc. This in turn enables popular consensus building amongst a wider spectrum of people than a kinship group. Despite this basic distinction, democracy (understood as adult franchise, formation of political parties and freedom of political thought and action) and ethnic politics co- exist without any apparent contradiction in a region where democracy has been introduced fairly recently as a replacement for monarchical, feudal or colonial systems. -

Chief Minister Lays Foundation Stone of Kali Darshan Yatra

SIkKIM HERALD Vol. 64 No. 51 visit us at www.ipr.sikkim.gov.in Gangtok (Tuesday) October 20, 2020 Regd. No.WB/SKM/01/2020-2022 Governor pays homage to former Chief Minister lays foundation President APJ Abdul Kalam stone of Kali Darshan Yatra Gangtok, October 17: The Chief Minister Mr. Prem Singh Tamang laid the foundation stone of Kali Darshan Yatra at Gadi under West Pendam Constituency, today. The function also had the presence of Speaker (SLA) Mr. L. B. Das, Minister for Tourism and Civil Aviation Department, Mr. B.S. Panth, MLA (Rhenock Constituency), Mr. B.K. Sharma, Press Advisor to Chief Minister Mr. C. P. Sharma, Advisors, Chairperson, Chairmen along with the public of West Pendam and Rhenock Constituencies. It may be mentioned here that the Kali Darshan Yatra project will be developed by Gangtok, October 15: The The Governor stated that Dr. Tourism and Civil Aviation Governor Mr. Ganga Prasad paid Kalam was “an embodiment of Department and will comprise of projects have also been that the foundation stone of Kali homage to former President, compassion, wisdom and a walkway with flat stone designed. Darshan Yatra was laid with an Bharat Ratna, APJ Abdul Kalam, strength” and his words and pitching along Gadi/Alley Bhir Thereafter, the Chief aim to develop a walking trail on his birth anniversary at Raj works, have inspired millions leading to Kali Devi Mandir Minister along with other from Gadi Bhir to the Mandir Bhavan, today. The Governor across the globe to believe in their through a tough rocky cliff (Gadi dignitaries attended an official which passes through a tough offered floral tribute to a portrait dreams.