Weld County, Colorado, Historic Agriculture Context, 612 (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado History Chronology

Colorado History Chronology 13,000 B.C. Big game hunters may have occupied area later known as Colorado. Evidence shows that they were here by at least 9200 B.C. A.D. 1 to 1299 A.D. Advent of great Prehistoric Cliff Dwelling Civilization in the Mesa Verde region. 1276 to 1299 A.D. A great drought and/or pressure from nomadic tribes forced the Cliff Dwellers to abandon their Mesa Verde homes. 1500 A.D. Ute Indians inhabit mountain areas of southern Rocky Mountains making these Native Americans the oldest continuous residents of Colorado. 1541 A.D. Coronado, famed Spanish explorer, may have crossed the southeastern corner of present Colorado on his return march to Mexico after vain hunt for the golden Seven Cities of Cibola. 1682 A.D. Explorer La Salle appropriates for France all of the area now known as Colorado east of the Rocky Mountains. 1765 A.D. Juan Maria Rivera leads Spanish expedition into San Juan and Sangre de Cristo Mountains in search of gold and silver. 1776 A.D. Friars Escalante and Dominguez seeking route from Santa Fe to California missions, traverse what is now western Colorado as far north as the White River in Rio Blanco County. 1803 A.D. Through the Louisiana Purchase, signed by President Thomas Jefferson, the United States acquires a vast area which included what is now most of eastern Colorado. While the United States lays claim to this vast territory, Native Americans have resided here for hundreds of years. 1806 A.D. Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike and small party of U.S. -

Regional Annual Report

2018 REGIONAL ANNUAL REPORT Bringing Communities Hope A Message from the Regional Executive Reflecting on the 2018 Fiscal Year (July 1, 2017 - June 30, 2018), I take great pride in the dedication and spirit of our remarkable American Red Cross volunteers and employees. The year included the most significant disaster season we have seen in over a decade, yet, with the support of our donors and volunteers, we rose to every occasion when called. I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the commitment and generosity of our donors. Together, we have accomplished so much in our community. Day and night, the Red Cross offered a helping hand and understanding ear to people in Colorado and Wyoming—whether it was bringing relief and hope to families picking up the pieces following a disaster or providing support and care for our military members, veterans and their loved ones. While meeting these immediate needs, trained Red Cross volunteers also partnered with fire departments, community groups and corporations to install free smoke alarms and to teach our neighbors lifesaving preparedness skills in our first annual Sound the Alarm national event. Over a busy year in the Colorado & Wyoming Region, our community volunteers and local partners stepped up time and again, joining with the Red Cross to bring vital assistance to people in need. In this report, you will learn more about the wide variety of work done through your local Red Cross chapters—who bring our mission to life every day. I am grateful to everyone who selflessly contributed their time, expertise and financial resources to support the Red Cross in Fiscal Year 2018. -

Church History 6900 W

Page 2 - The Denver Catholic Register, Wed., January 2, 1985 Archbishop St 'doing well' Archbishop James V Casey is " doing very well. 011 He's still tired but everything looks very positive," according to Bishop George R. Evans at press time. The archbishop was released from St Joseph's Hospital Dec. 22. He was put back in the hospital Dec. fOI 12 to receive treatment for hepatitis. According to Bishop Evans. a series of tests done on the archbishop before he was released showed no signs of any other problems. 'Pa1 Bishop Evans added that the archbishop, who is recuperating in his southwest Denver home, has been able to take walks outdoors Archbishop Casey has been recuperating from an for abdominal anuerysm that ruptured Oct 27. T, Permanent diaconate turned Metzge regular orientation program brain d An orientation program for the permanent diaconate No formation class will be held Jan. 5, at St. ThorMs' Seminary, even h, in Bonfils Hall, from 1:30 to 4 p.m. undersJ Father Marcian O'Meara, director of the Permanent 'One c Diaconate, along with other members of the formation team will be present to explain the four-year formation come 1 progr'arn leading to ordination as permanent deacons. Wives age:·c of men interested in the permanent diaconate are also apartrr: welcome to attend. age lhE Five candidates for the Denver archdiocese, along with LOI three candidates for the Pueblo diocese, are now in for the c·ou mation on the Western Slope, and 18 candidates for the ftrsl t:'> Father Bliss, center, is shown walking with Jesuit Father Robert Hagen ,n Rome during the worldwide retreat for Denver archdiocese, along with two candidates for the priffta and deacons In October. -

Livestock and Landscapes

SUSTAINABILITY PATHWAYS LIVESTOCK AND LANDSCAPES SHARE OF LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION IN GLOBAL LAND SURFACE DID YOU KNOW? Agricultural land used for ENVIRONMENT Twenty-six percent of the Planet’s ice-free land is used for livestock grazing LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION and 33 percent of croplands are used for livestock feed production. Livestock contribute to seven percent of the total greenhouse gas emissions through enteric fermentation and manure. In developed countries, 90 percent of cattle Agricutural land used for belong to six breed and 20 percent of livestock breeds are at risk of extinction. OTHER AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION SOCIAL One billion poor people, mostly pastoralists in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, depend on livestock for food and livelihoods. Globally, livestock provides 25 percent of protein intake and 15 percent of dietary energy. ECONOMY Livestock contributes up to 40 percent of agricultural gross domestic product across a significant portion of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa but receives just three percent of global agricultural development funding. GOVERNANCE With rising incomes in the developing world, demand for animal products will continue to surge; 74 percent for meat, 58 percent for dairy products and 500 percent for eggs. Meeting increasing demand is a major sustainability challenge. LIVESTOCK AND LANDSCAPES SUSTAINABILITY PATHWAYS WHY DOES LIVESTOCK MATTER FOR SUSTAINABILITY? £ The livestock sector is one of the key drivers of land-use change. Each year, 13 £ As livestock density increases and is in closer confines with wildlife and humans, billion hectares of forest area are lost due to land conversion for agricultural uses there is a growing risk of disease that threatens every single one of us: 66 percent of as pastures or cropland, for both food and livestock feed crop production. -

Agricultural Land Tax in Montana

What follows is a summary of how Montana and seven other Western states handle agricultural land for property tax purposes. The states included are Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Colorado. The topics are Definition of Agricultural Land Use, Income and Acreage Requirements, and Methodology for Valuing Agricultural Land. There is some overlap in the topics because each state adds its own nuances to how it defines and values agricultural land and how it describes those procedures. Definition of Agricultural Land Use MONTANA The term "agricultural" for property tax purposes, refers to "the production of food, feed, and fiber commodities, livestock and poultry, bees, fruits and vegetables, and sod, ornamental, nursery, and horticultural crops that are raised, grown, or produced for commercial purposes." The term also refers to the raising of domestic animals and wildlife in domestication or a captive environment. [Section 15-1-101(a), MCA)] WYOMING The term "agricultural land", for property tax purposes, means "land which has been used or employed during the previous two years and presently is being used and employed for the primary purpose of obtaining a monetary profit as agricultural or horticultural use or any combination thereof is to be agricultural land...unless legally zoned otherwise by a zoning authority." [Section 39-13-101(a)(iii), WY ST] NORTH DAKOTA "'Agricultural property' means platted or unplatted lands used for raising agricultural crops or grazing farm animals, except lands platted and assessed as agricultural property prior to March 30, 1981, shall continue to be assessed as agricultural property until put to a use other than raising agricultural crops or grazing farm animals." North Dakota code also provides that "property platted on or after March 30, 1981, is not agricultural property when any four of the following conditions exist: a. -

Uchealth Pharmacy Network Contact Information

UCHealth Pharmacy Network Contact Information For general questions about University of Colorado Health (UCHealth) Pharmacies: Call 720-848-3377 (voicemail only line) or email: [email protected] Request refills online through My Health Connection: myhealthconnection.uchealth.org Metro Denver Region University of Colorado University of Colorado Hospital University of Colorado Hospital Hospital Atrium Pharmacy IDGP Pharmacy AOP Pharmacy 12605 E. 16th, Room 1054 1635 Aurora Ct., Room 7284 1635 Aurora Ct., Room 1012 Mail Stop A027, Aurora, CO 80045 Mail Stop F702, Aurora, CO 80045 Mail Stop F702, Aurora, CO 80045 Hours: M-F 8:00 am – 8:30 pm Hours: M-F 8:30 am – 5:00 pm Hours: M-F 8:00 am – 6:00 pm Sat - Sun: 9:00 am – 5:00 pm Phone: (720) 848-4081 Phone: (720) 848-1020 Phone: (720) 848-4083 Fax: (720) 848-4082 Fax: (720) 848-1040 Fax: (720) 848-4084 *ScriptCenter Services Available Highlands Ranch Hospital Pharmacy University of Colorado Hospital University of Colorado Hospital Lowry Pharmacy 1500 Park Central Dr. Rm G205 ED Pharmacy 8111 E. Lowry Blvd, Suite 110 Highlands Ranch, CO 80129 12605 E. 16th Ave, Room 1.51 Mail Stop B01, Denver, CO 80230 Hours: M-F 8:00 am – 7:00 pm Aurora, CO 80045 Hours: M-F 8:30 am - 12:45 pm & Sat-Sun: 9am – 5:00pm Hours: Open 24/7 1:15 pm - 5:00 pm Phone: (720) 848-8368 Phone: (720) 848-9590 After Hours Services Available Upon Request Fax: (720) 848-9593 Phone: (720) 516-0070 Fax: (720) 516-0223 *ScriptCenter Services Available Northern Colorado Region Boulder Health Center Longs Peak Hospital Pharmacy Poudre Valley Hospital Pharmacy 1750 E. -

Increase Food Production Without Expanding Agricultural Land

COURSE 2 Increase Food Production without Expanding Agricultural Land In addition to the demand-reduction measures addressed in Course 1, the world must boost the output of food on existing agricultural land. To approach the goal of net-zero expansion of agricultural land, improvements in crop and livestock productivity must exceed historical rates of yield gains. Chapter 10 assesses the land-use challenge, based on recent trend lines. Chapters 11–16 discuss possible ways to increase food production per hectare while adapting to climate change. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 10. Assessing the Challenge of Limiting Agricultural Land Expansion .............................147 Chapter 11. Menu Item: Increase Livestock and Pasture Productivity ........................................167 Chapter 12. Menu Item: Improve Crop Breeding to Boost Yields ..............................................179 Chapter 13. Menu Item: Improve Soil and Water Management ...............................................195 Chapter 14. Menu Item: Plant Existing Cropland More Frequently ........................................... 205 Chapter 15. Adapt to Climate Change ........................................................................... 209 Chapter 16. How Much Could Boosting Crop and Livestock Productivity Contribute to Closing the Land and Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Gaps? .....................................................221 Creating a Sustainable Food Future 145 146 WRI.org CHAPTER 10 ASSESSING THE CHALLENGE OF LIMITING AGRICULTURAL LAND EXPANSION How hard will it be to stop net expansion of agricultural land? This chapter evaluates projections by other researchers of changes in land use and explains why we consider the most optimistic projections to be too optimistic. We discuss estimates of “yield gaps,” which attempt to measure the potential of farmers to increase yields given current crop varieties. Finally, we examine conflicting data about recent land-cover change and agricultural expansion to determine what they imply for the future. -

State of Colorado University of Northern Colorado

State of Colorado University of Northern Colorado Financial and Compliance Audit Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2004 and 2003 LEGISLATIVE AUDIT COMMITTEE 2004 MEMBERS (Effective August 2, 2004) Representative Val Vigil Vice-Chairman Senator Norma Anderson Representative Fran Coleman Representative Pamela Rhodes Representative Lola Spradley Senator Stephanie Takis Senator Jack Taylor Senator Ron Tupa Office of the State Auditor Staff Joanne Hill State Auditor Sally Symanski Deputy State Auditor Mary Pearce Legislative Auditor BKD, LLP Contract Auditor State of Colorado University of Northern Colorado June 30, 2004 and 2003 Contents Report Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendation Locator..................................................................................................... 4 Description of the University of Northern Colorado ........................................................... 5 Auditor’s Findings and Recommendations ......................................................................... 6 Disposition of Prior Year Audit Recommendations.......................................................... 10 Independent Accountants’ Report on Financial Statements and Supplementary Information ............................................................................................. 11 Management’s Discussion and Analysis........................................................................... 13 Financial Statements Statements -

Sustainable Intensive Agriculture: High Technology and Environmental Benefits

University of Arkansas School of Law [email protected] $ (479) 575-7646 An Agricultural Law Research Article Sustainable Intensive Agriculture: High Technology and Environmental Benefits by Drew L. Kershen Originally published in KANSAS JOURNAL OF LAW AND PUBLIC POLICY 16 KAN. J. L. & PUB. POL’Y 424 (2007) www.NationalAgLawCenter.org SUSTAINABLE INTENSIVE AGRICULTURE: HIGH TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS Drew L. Kershen- I. PREFACE In the coming decades, agriculture faces three significant challenges. While these challenges will manifest themselves in ways unique to the cultural, socio-economic, and political conditions of different countries, developed and developing nations alike will face these challenges. Moreover, for the purposes of this article, the author assumes these challenges are truisms; consequently, there is no need to cite authority to support the author's identification and assertions. 1 Agriculture faces an agronomic challenge. Millions of people are still hungry in our world. Moreover, the world's population will continue to grow . for at least several decades. Agriculture must produce the food necessary to provide the people of the world-including those who presently have the money to feel secure about their daily bread-with an adequate supply of nutritious food'. "Agriculture must first be about food production for the survival and health of human beings, Agriculture faces an environmental challenge. It cannot produce the food needed for human beings if it exhausts or abuses Earth's soil, water, air, and biodiversity. Moreover, the general public, governments, and civil organizations from all societal sectors (academic, business, consumer, for profit and non-profit, public interest, and scientific) demand that agriculture Earl Sneed Centennial Professor of Law, University of Oklahoma, College of Law. -

Agriculture and Food Processing in Armenia

SAMVEL AVETISYAN AGRICULTURE AND FOOD PROCESSING IN ARMENIA YEREVAN 2010 Dedicated to the memory of the author’s son, Sergey Avetisyan Approved for publication by the Scientifi c and Technical Council of the RA Ministry of Agriculture Peer Reviewers: Doctor of Economics, Prof. Ashot Bayadyan Candidate Doctor of Economics, Docent Sergey Meloyan Technical Editor: Doctor of Economics Hrachya Tspnetsyan Samvel S. Avetisyan Agriculture and Food Processing in Armenia – Limush Publishing House, Yerevan 2010 - 138 pages Photos courtesy CARD, Zaven Khachikyan, Hambardzum Hovhannisyan This book presents the current state and development opportunities of the Armenian agriculture. Special importance has been attached to the potential of agriculture, the agricultural reform process, accomplishments and problems. The author brings up particular facts in combination with historic data. Brief information is offered on leading agricultural and processing enterprises. The book can be a useful source for people interested in the agrarian sector of Armenia, specialists, and students. Publication of this book is made possible by the generous fi nancial support of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and assistance of the “Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development” Foundation. The contents do not necessarily represent the views of USDA, the U.S. Government or “Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development” Foundation. INTRODUCTION Food and Agriculture sector is one of the most important industries in Armenia’s economy. The role of the agrarian sector has been critical from the perspectives of the country’s economic development, food safety, and overcoming rural poverty. It is remarkable that still prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia made unprecedented steps towards agrarian reforms. -

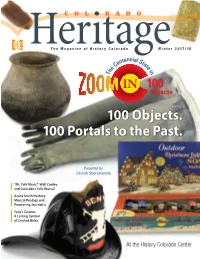

100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past

The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past. Presented by Colorado State University “Mr. Folk Music”: Walt Conley and Colorado’s Folk Revival Azalia Smith Hackley: Musical Prodigy and Pioneering Journalist Tony’s Conoco: A Lasting Symbol of Crested Butte At the History Colorado Center Steve Grinstead Managing Editor Micaela Cruce Editorial Assistance Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services How Did We Become Colorado? 4 Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by The artifacts in Zoom In serve as portals to the past. History Colorado, contains articles of broad general By Julie Peterson and educational interest that link the present to the 8 Azalia Smith Hackley past. Heritage is distributed quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of A musical prodigy made her name as a journalist and activist. higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented when By Ann Sneesby-Koch submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications 16 “Mr. Folk Music” office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Walt Conley headlined the Colorado folk-music revival. Publications office. History Colorado disclaims By Rose Campbell responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion made by contributors. History Colorado also publishes 24 Tony’s Conoco Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, events, A symbol of Crested Butte embodies memories and more. and exhibition listings. By Megan Eflin Postage paid at Denver, Colorado All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. -

Northern Colorado Regional Cluster Strategy

MARCH 2020 NORTHERN COLORADO REGIONAL CLUSTER STRATEGY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Northern Colorado Regional Economic Development Initiative (NoCo REDI) represents a network of economic development organizations working to coordinate regional economic development efforts. NoCo REDI recognizes that economic benefits in one community benefit all, due to the interconnected nature of the regional economy. Working together allows for greater impact in the region—“We are one economy.” The objective of this collaboration is to increase the region’s economic resilience and improve the business ecosystem. A huge thank you to the many members of NoCo REDI who contributed their time and intellect to this project. City of Evans Economic Development Town of Berthoud Business Development Office City of Fort Collins Economic Health Office Town of Erie Economic Development Department City of Fort Lupton Town of Firestone Economic Development City of Greeley Economic Health and Housing Town of Wellington Economic Development City of Loveland Economic Development Department Town of Windsor Economic Development Department Fort Collins Area Chamber of Commerce Upstate Colorado Economic Development Larimer County Economic and Workforce Development ABOUT THE PROJECT SPONSORS AND CONSULTING TEAM The City of Fort Collins provided funding and staff support for the study through its Economic Health Office. The city's Economic Health Office focuses on preserving vitality and promoting economic health in Fort Collins as part of the Sustainability Services division. Contact: