Electric Ascension the Wire __.

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMAIL INTERVIEW with Pachi Tapiz, Spanish Music Critic December 2009 to February 2010. Published in Spanish by Tomajazz in June

EMAIL INTERVIEW with Pachi Tapiz, Spanish Music Critic December 2009 to February 2010. Published in Spanish by Tomajazz in June 2010 http://www.tomajazz.com/perfiles/ochs_larry_2010.html Q1: Why did Rova decide to join its creative forces with Nels Cline Singers? Ochs: Rova has employed all these guys over the past 12 years or so in different bands. Scott Amendola and I work together in Larry Ochs Sax & Drumming Core as well as in a new band called Kihnoua featuring the great vocals of Korean‐born Dohee Lee. (That band plays in Europe very soon, but unfortunately nothing in Spain. I thought “maybe” some place there would hire this band after all the news / nonsense in December, but no one called me except journalists. No, I was not surprised that no one called. But I do feel strongly that Kihnoua is a great band, but I would agree with those on the other side; it is not a jazz band. Jazz influenced? Definitely; jazz band? No. I will send you the just released CD in early May when I return from the tour.) Sorry for the digression: So Scott performed first with Rova in a big piece of mine in 1998 called “Pleistocene: The Ice Age.” (as well as Adams’ and Raskin pieces that same evening.) And he worked in Vancouver with us on Electric Ascension in 2005 along with Devin Hoff and Nels, of course. Nels recorded Electric Ascension with us live in 2003, played on every performance of that “event” until 2009, and he is “the man” in free jazz when it comes to playing updated versions of late‐period Coltrane on guitar. -

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. -

It's All Good

SEPTEMBER 2014—ISSUE 149 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JASON MORAN IT’S ALL GOOD... CHARLIE IN MEMORIAMHADEN 1937-2014 JOE • SYLVIE • BOBBY • MATT • EVENT TEMPERLEY COURVOISIER NAUGHTON DENNIS CALENDAR SEPTEMBER 2014 BILLY COBHAM SPECTRUM 40 ODEAN POPE, PHAROAH SANDERS, YOUN SUN NAH TALIB KWELI LIVE W/ BAND SEPT 2 - 7 JAMES CARTER, GERI ALLEN, REGGIE & ULF WAKENIUS DUO SEPT 18 - 19 WORKMAN, JEFF “TAIN” WATTS - LIVE ALBUM RECORDING SEPT 15 - 16 SEPT 9 - 14 ROY HARGROVE QUINTET THE COOKERS: DONALD HARRISON, KENNY WERNER: COALITION w/ CHICK COREA & THE VIGIL SEPT 20 - 21 BILLY HARPER, EDDIE HENDERSON, DAVID SÁNCHEZ, MIGUEL ZENÓN & SEPT 30 - OCT 5 DAVID WEISS, GEORGE CABLES, MORE - ALBUM RELEASE CECIL MCBEE, BILLY HART ALBUM RELEASE SEPT 23 - 24 SEPT 26 - 28 TY STEPHENS (8PM) / REBEL TUMBAO (10:30PM) SEPT 1 • MARK GUILIANA’S BEAT MUSIC - LABEL LAUNCH/RECORD RELEASE SHOW SEPT 8 GATO BARBIERI SEPT 17 • JANE BUNNETT & MAQUEQUE SEPT 22 • LOU DONALDSON QUARTET SEPT 25 LIL JOHN ROBERTS CD RELEASE SHOW (8PM) / THE REVELATIONS SALUTE BOBBY WOMACK (10:30PM) SEPT 29 SUNDAY BRUNCH MORDY FERBER TRIO SEPT 7 • THE DIZZY GILLESPIE™ ALL STARS SEPT 14 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES THE FLOWDOWN SEPT 5 • EAST GIPSY BAND w/ TIM RIES SEPT 6 • LEE HOGANS SEPT 12 • JOSH DAVID & JUDAH TRIBE SEPT 13 RABBI DARKSIDE SEPT 19 • LEX SADLER SEPT 20 • SUGABUSH SEPT 26 • BROWN RICE FAMILY SEPT 27 Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps with Hutch or different things like that. like things different or Hutch with sometimes. -

Larry Ochs' Interview with Luca Canini for Allaboutjazzitalia.Com Via Email in Winter 2013.(Published April 2013.) Questions

Larry Ochs’ interview with Luca Canini for AllAboutJazzItalia.com via email in winter 2013.(published April 2013.) Questions in bold. Some years ago, when I first listened to “Electric Ascension”, I was shocked by the intensity and power of the performance: past/future, tradition/innovation. That disc and the few concerts around the world are a deep reflection on jazz, history, improvisation, sound. But everything started back in 1995, when Rova decided to celebrate the 30th anniversary of John Coltrane’s masterpiece. Can you tell me something about the birth of the project? How do you decide to approach such a “problematic” piece (if you consider Ascension a “piece”)? And do you remember the first time you listen to Ascension? I think Coltrane’s “Ascension” is one of the great jazz compositions of all time. A great formal structure; a great piece. Not that I consider myself an expert on all jazz music. I really don’t. But I am an expert on the greatness of that composition. We have played it 11 times as “Electric Ascension.” And yes it is true that we re- arranged the piece and changed the instrumentation, but the basic composition “Ascension” is absolutely at the center of “Electric Ascension;” it totally influences all the music we play in the spontaneous performance. There is no doubt of that. I remember seeing John Coltrane live at the Village Vanguard with his late great quartet in 1967. I was 18. The music overwhelmed me completely. There were maybe 20 people there for that second set of their night. -

Festival Report: Hudson Valley Jazz Fest

FESTIVAL REPORT Hudson Valley Jazz Fest Detroit Jazz Fest Guelph Jazz Festival by Laurence Donohue-Greene by Greg Thomas by Ken Waxman m o c . d r o w z z a j . w w w / / g : r p e t t b h n e t r s o z r t i n a F n K o y r C n ’ a e O G L n y y a b b s o o u t t S o o ) h h c P P ( String Trio of New York Wynton Marsalis Sextet Darius Jones & Matthew Shipp For New Yorkers looking to bolt out of the city for a The 2012 Detroit Jazz Festival held over Labor Day A specter was haunting the 2012 Guelph Jazz Festival day-trip or long weekend, Warwick, an hour’s drive weekend was a cornucopia of value at the perfect price: (GJF): the ghost of John Coltrane. Coltrane was honored northeast, is a great destination. From fall foliage and free. Considering the headliners - Sonny Rollins, in direct and indirect ways throughout the five-day apple picking (the 24th Applefest is Oct. 14th) to its Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard (the Artist-in- festival, which takes places annually in this college third annual jazz festival (Aug. 16th-19th), the small Residence), Chick Corea/Gary Burton, Wayne Shorter, town, 100 kilometers west of Toronto. This year’s town is bustling with activity. Kenny Garrett and Pat Metheny - the vision of the new edition (Sep. 5th-9th), featured two live performances The Hudson Valley Jazz Festival (né Warwick Jazz Artistic Director Christopher Collins can be summed of Ascension, Coltrane’s 1965 masterwork, one by an Festival) is the brainchild of Steve Rubin, a jazz up by a WBGO radio tag line: real jazz, right now. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

In This Issue

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC In This Issue ab baars Charles Gayle woody herman Coleman Hawkins kidd jordan joe lovano john and bucky pizzarelli lou marini Daniel smith 2012 Critic’s poll berlin jazz fest in photos Volume 39 Number 1 Jan Feb March 2013 SEATTLE’S NONPROFIT earshotCREATIVE JAZZ JAZZORGANIZATION Publications Memberships Education Artist Support One-of-a-kind concerts earshot.org | 206.547.6763 All Photos by Daniel Sheehan Cadence The Independent Journal of Creative Improvised Music ABBREVIATIONS USED January, February, March 2013 IN CADENCE Vol. 39 No. 1 (403) acc: accordion Cadence ISSN01626973 as: alto sax is published quarterly online bari s : baritone sax and annually in print by b: bass Cadence Media LLC, b cl: bass clarinet P.O. Box 13071, Portland, OR 97213 bs: bass sax PH 503-975-5176 bsn: bassoon cel: cello Email: [email protected] cl: clarinet cga: conga www.cadencejazzmagazine.com cnt: cornet d: drums Subscriptions: 1 year: el: electric First Class USA: $65 elec: electronics Outside USA : $70 Eng hn: English horn PDF Link and Annual Print Edition: $50, Outside USA $55 euph: euphonium Coordinating Editor: David Haney flgh: flugelhorn Transcriptions: Colin Haney, Paul Rogers, Rogers Word flt: flute Services Fr hn: French horn Art Director: Alex Haney g: guitar Promotion and Publicity: Zim Tarro hca: harmonica Advisory Committee: kybd: keyboards Jeanette Stewart ldr: leader Colin Haney ob: oboe Robert D. Rusch org: organ perc: percussion p: piano ALL FOREIGN PAYMENTS: Visa, Mastercard, Pay Pal, and pic: piccolo Discover accepted. rds: reeds POSTMASTER: Send address change to Cadence Magazine, P.O. -

Electric Ascension Paris Transatlantic Magazine 05.6

JAZZ ROVA::ORKESTROVA 2003 ELECTRIC ASCENSION Atavistic ALP 159 CD Coltrane's Ascension has, like his A Love Supreme , long been something of an unassailable summit in jazz history, but as any seasoned mountaineer will tell you, there's no such thing as an unassailable summit. A Love Supreme has after all already been scaled by Branford Marsalis, and Nels Cline and Gregg Bendian released an extraordinary version of Interstellar Space a while back, so it was only a matter of time before somebody got round to tackling Ascension . And what a spectacularly good job the Orkestrova has made of it. Joining ROVA's core members – Bruce Ackley, Steve Adams, Larry Ochs and Jon Raskin, on, respectively, soprano, alto, tenor and baritone saxes – are Chris Brown on electronics, Otomo Yoshihide on turntables and electronics, Ikue Mori on drum machines and sampler, Nels Cline – the same – on electric guitar, Fred Frith on bass, Don Robinson on drums and violinists Carla Kihlstedt and Jenny Scheinman. Wait, Ascension with violins? Yes – and it's a master stroke too: where the Coltrane original was a heaving, turbulent horn-heavy affair, this version, recorded live for KFJC FM in Los Altos CA on February 8th 2003, opens the windows on to a landscape of bright colours and variegated textures that keeps the music fresh and buoyant right through its heroic 64-minute span. The individual and ensemble performances are simply inspired, from Ochs's opening tenor broadside onwards, and the whole glorious edifice is underpinned by Frith's marvellously spacious and melodic bass work, which keeps the flame of the original tiny modal cell burning brightly even in the wilder moments. -

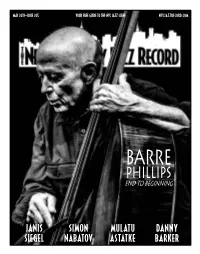

PHILLIPS End to BEGINNING

MAY 2019—ISSUE 205 YOUR FREE guide TO tHe NYC JAZZ sCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BARRE PHILLIPS END TO BEGINNING janis simon mulatu danny siegel nabatov astatke barker Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2019—ISSUE 205 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@nigHt 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : janis siegel 6 by jim motavalli [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist Feature : simon nabatov 7 by john sharpe [email protected] General Inquiries: on The Cover : barre pHillips 8 by andrey henkin [email protected] Advertising: enCore : mulatu astatke 10 by mike cobb [email protected] Calendar: lest we Forget : danny barker 10 by john pietaro [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotligHt : pfMENTUM 11 by robert bush [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or obituaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] Cd reviews 14 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, misCellany 33 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, event Calendar Tom Greenland, George Grella, 34 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mike Cobb, Pierre Crépon, George Kanzler, Steven Loewy, Franz Matzner, If jazz is inherently, wonderfully, about uncertainty, about where that next note is going to Annie Murnighan, Eric Wendell come from and how it will interact with all that happening around it, the same can be said for a career in jazz. -

Fred Ho Enrico Pieranunzi Russell

November 2011 | No. 115 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Fred • Enrico • Russell • Auand • Festival • Event Ho Pieranunzi Garcia Records Reports Calendar John Coltrane is rightly considered one of the innovators in jazz even though his career as a leader lasted only a brief, if remarkably prolific, decade before his tragic death in 1967 at 40. But most critical acclaim is heaped on the period before New York@Night 1964. Ascension, recorded in 1965, is considered by many the end of Coltrane as a 4 legitimate jazz musician, as he moved away from his roots into the burgeoning Interview: Fred Ho avant garde and free jazz scenes. But another group see Coltrane’s shift in this direction helping to propel these new forms, not least because of his championing 6 by Ken Waxman of such musicians as Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, John Tchicai and Marion Artist Feature: Enrico Pieranunzi Brown, now all legends in their own rights. This month two tributes (at Le Poisson Rouge and Jazz Standard) will recreate Coltrane’s controversial work with allstar by Laurel Gross 7 casts of musicians from across the modern spectrum, a living testament to the On The Cover: John Coltrane’s Ascension music’s continuing impact. For our cover story this month, we’ve spoken with by Marc Medwin participants from the original Ascension album plus other musicians who have 9 done their own interpretations and those involved in the upcoming tributes. Encore: Lest We Forget: Two other controversial figures are baritone saxophonist/composer Fred Ho 10 (Interview), whose political statements and inclusive musical blending have Russell Garcia Sam Jones resulted in some monumental works over the past few decades, and Italian pianist by Andy Vélez by Donald Elfman Enrico Pieranunzi (Artist Feature), who mixes the classical music of his native Megaphone VOXNews Europe with his adopted jazz in a mélange that challenges the assumptions of both by Denny Zeitlin by Suzanne Lorge art forms. -

Julyissuesingle.Pdf

The Independent Journal ofCreative Improvised Music cadence Vol 38 No3 JUL AUG SEP 2012 The New York City Jazz Record EXCLUSIVE CONTENT ON JAZZ & IMPROVISED MUSIC IN NEW YORK CITY COMPETITIVE & EFFECTIVE ADVERTISING: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTIONS AND GENERAL INFO: [email protected] FOLLOW US ON TWITTER: @NYCJAZZRECORD www.nycjazzrecord.com Cadence The Independent Journal of Creative Improvised Music July - August - September 2012 ABBREVIATIONS USED Vol. 38 No. 3 (401) IN CADENCE Cadence ISSN01626973 is published quarterly online acc: accordion and annually in print by as: alto sax Cadence Media LLC, bari s : baritone sax P.O. Box 282, Richland, OR 97870 b cl: bass clarinet bs: bass sax PH 315-289-1444 bsn: bassoon cel: cello Email: [email protected] cl: clarinet cga: conga www.cadencejazzmagazine.com cnt: cornet d: drums Subscriptions: 1 year: el: electric First Class USA: $65 elec: electronics Outside USA : $70 Eng hn: English horn PDF Link and Annual Print Edition: $50, Outside USA $55 euph: euphonium Coordinating Editor: David Haney flgh: flugelhorn Copy Editors: Kara D. Rusch, Jeffrey D. Todd flt: flute Transcriptions: Colin Haney, Paul Rogers, Rogers Word Fr hn: French horn Services g: guitar Art Director: Alex Haney hca: harmonica Crosswords: Ava Haney Martin kybd: keyboards Promotion and Publicity: Tiffany Rozee ldr: leader Advisory Committee: ob: oboe Jeanette Stewart org: organ Colin Haney perc: percussion Robert D. Rusch p: piano Abe Goldstein pic: piccolo rds: reeds ALL FOREIGN PAYMENTS: Visa, Mastercard, Pay Pal, and ss: soprano sax Discover accepted. sop: sopranino sax POSTMASTER: Send address change to Cadence Magazine, P.O. synth: synthesizer Box 282, Richland, OR 97870 ts: tenor sax © Copyright 2012 Cadence Magazine tbn: trombone Published by Cadence Media, LLC. -

George Benson Charlie Haden Dave Holland William Hooker Jane Monheit Steve Swallow CD Reviews International Jazz News Jazz Stories

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC George Benson Charlie Haden Dave Holland William Hooker Jane Monheit Steve Swallow CD Reviews International jazz news jazz stories Volume 39 Number 4 Oct Nov Dec 2013 More than 50 concerts in venues all around Seattle Keith Jarrett, Gary Peacock, & Jack DeJohnette • Brad Mehldau Charles Lloyd Group w/ Bill Frisell • Dave Douglas Quintet • The Bad Plus Philip Glass • Ken Vandermark • Paal Nilssen-Love • Nicole Mitchell Bill Frisell’s Big Sur Quintet • Wayne Horvitz • Mat Maneri SFJAZZ Collective • John Medeski • Paul Kikuchi • McTuff Cuong Vu • B’shnorkestra • Beth Fleenor Workshop Ensemble Peter Brötzmann • Industrial Revelation and many more... October 1 - November 17, 2013 Buy tickets now at www.earshot.org 206-547-6763 Charles Lloyd photo by Dorothy Darr “Leslie Lewis is all a good jazz singer should be. Her beautiful tone and classy phrasing evoke the sound of the classic jazz singers like Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah aughan.V Leslie Lewis’ vocals are complimented perfectly by her husband, Gerard Hagen ...” JAZZ TIMES MAGAZINE “...the background she brings contains some solid Jazz credentials; among the people she has worked with are the Cleveland Jazz Orchestra, members of the Ellington Orchestra, John Bunch, Britt Woodman, Joe Wilder, Norris Turney, Harry Allen, and Patrice Rushen. Lewis comes across as a mature artist.” CADENCE MAGAZINE “Leslie Lewis & Gerard Hagen in New York” is the latest recording by jazz vocalist Leslie Lewis and her husband pianist Gerard Hagen. While they were in New York to perform at the Lehman College Jazz Festival the opportunity to record presented itself.