Daulat Singh Kothari (1906–1993)∗ Scientist, Teacher, Administrator and Humanist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Professor Daulat Singh Kothari: a Profile

Defence Science Journal, Vol 44, No 3, July 1994, pp 189-192 @ 1994, DESIDOC Professor Daulat Singh Kothari: A ProfIle A. Nagaratnam Emeritus Scientist, Defence Metallurgical Research Laboratory, Hyderabad-500 258 and N.S. Venkatesan 8-411, Suiya Kiran Apts, 42, Netaji Road, 8angalore-560 005 . 1. INTRODUCTION last days of his life; this association continued in an In the passing away of Professor DS Kothari unbroken fashion even when he was the Scientific (Doctorsaab, as he was generally called with affection Adviser to the Minister of Defence and the Chairman and respect), an institution, an era, and a legend have of the University Grants Commission. It is no surprise come t.O:;~ end. He was an outstanding physicist, an that the Vice-Chancellor of Delhi University once said: educationist with a' vision, an inspiring teacher, the 'Kothari is the conscience of Delhi University'. architect of defence science in our country , and, above Professor Kothari was easily approachable by everyone , all, a great human being who symbolized the noblest high or low. He had an extraordinary memory for traditions of Indian culture. He combined in himself names, and an interaction with hiq1 was an unforgettable profound scholarship, simplicity to the point of experience. asceticism, humility, soft-spokenness, warmth, enlightenment, tolerance, as well as a passionate and 2. BRIEF BIODATA abiding concern for the welfare of humanity. A true Daulat Singh Kothari was born in Udaipur on 6 July lain, Kothari meticulously followed the principles of 1906. His.paternal grandfather was Mohan Lalji, who Right Conduct involving the practice of Ahimsa, Satya, was working in the Customs Department, and died in Asteya and A¥..rigraha. -

Journal of the National Human Rights Commission India Volume – 16 2017 EDITORIAL BOARD Justice Shri H

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION INDIA Volume – 16 2017 EDITORIAL BOARD Justice Shri H. L. Dattu Chairperson, NHRC Justice Shri P. C. Ghose Prof. Ranbir Singh Member, NHRC Vice-Chancellor, National Law University, Dwarka, New Delhi Justice Shri D. Murugesan Prof. T. K. Oommen Member, NHRC Emeritus Professor, Centre for the Study of Social Systems, School of Social Sciences, Shri S. C. Sinha Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Member, NHRC Smt. Jyotika Kalra Prof. Sanjoy Hazarika Member, NHRC Director, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, New Delhi Shri Ambuj Sharma Prof. S. Parasuraman Secretary General, NHRC Director, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai Shri J. S. Kochher Prof. Ved Kumari Joint Secretary (Trg. & Res.), Faculty of Law, Law Centre-I, NHRC University of Delhi, Delhi Dr. Ranjit Singh Prof. (Dr.) R. Venkata Rao Joint Secretary (Prog. & Admn.), Vice-Chancellor, National Law School NHRC of India University, Bangalore EDITOR Shri Ambuj Sharma, Secretary General, NHRC EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE Dr. M. D. S. Tyagi, Joint Director (Research), NHRC Shri Utpal Narayan Sarkar, AD (Publication), NHRC National Human Rights Commission Manav Adhikar Bhawan, C-Block, GPO Complex, INA New Delhi – 110 023, India ISSN : 0973-7596 ©2017, National Human Rights Commission All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the Publisher. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the articles incorporated in the Journal are of the authors and not of the National Human Rights Commission. The Journal of the National Human Rights Commission, Published by Shri Ambuj Sharma, Secretary General on behalf of the National Human Rights Commission, Manav Adhikar Bhawan, C-Block, GPO Complex, INA, New Delhi – 110 023, India. -

Publications of Professor Hardev Singh Virk (1972-2020)

Publications of Professor Hardev Singh Virk (1972-2020) List of Publications Classified under Interdisciplinary Areas of Research Section A: Elementary Particles & Cosmic Rays 1. Virk H. S. (1972) Proton-nucleon interactions at 14 GeV in nuclear emulsion. Nucl. Phys. B, 48, 476-486. 2. Tsai-Chu and Virk H S (1972) Energy loss and radiation length of electrons in nuclear emulsion. Compt. Rendu, Acad. of Sciences, Paris, 275,165-167. 3. Virk H S (1972) Identification of very inclined tracks in nuclear emulsion. Compt. Rendu, Acad. of Sciences, Paris, 275, 517-519. 4. Virk H S (1972) Study of nuclear interaction at high energy. Compt. Rendu, Acad. of Sciences, Paris, 275, 219-222. 5. Virk H S (1972) Do the particles with mass between that of electrons and muon exist? Compt. Rendu, Acad. of Sciences, Paris, 275, 709-711. 6. Virk H S and Bansal B K (1973) Law of gap length distribution and grain density of tracks. Compt. Rendu, Acad. of Sciences, Paris, 277, 65-66. 7. Virk H S (1974) Investigations of Tsytovich radiative corrections to ionisation loss of high energy electrons in nuclear emulsions. Nucl. Phys. B, 72, 393-396. 8. Virk H S (1974) Ionization of ultra relativistic electrons over Fermi plateau. Compt. Rendu, Acad. of Sciences, Paris, 278, 291-292. 9. Virk H S and Verma Veena (1984) Deutron-nucleus interactions at 10 GeV/c in BR-2 nuclear emulsion. Czech. J. Phys. B, 34, 1032-1037. 10. Virk H S (1979) Cosmic radiation effects in Dhajala meteorite. Curr. Sci., 48, 1067-1068. Section B: Geochronology (Fission Track Dating and Applications) 1. -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

Written Marks for the Post of Lib-RESULT.Xlsx

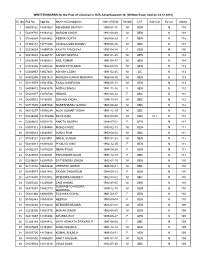

WRITTEN MARKS for the Post of Librarian in KVS Advertisement-14 (Written Exam held on 23.12.2018) Sl. No. Roll No. App No. Name of Candidates Date of Birth Gender CAT. Sub-Cat Ex-ser Marks 1 54005122 18353060 ABHISHEK BAJPAYI 1990-07-15 M GEN N 119 2 54209710 18392142 HARIOM SINGH 1993-08-29 M GEN N 118 3 51086084 18808862 REENA GUPTA 1980-06-29 F GEN N 118 4 51304151 18715944 VEMULA ANIL KUMAR 1990-08-16 M OBC N 117 5 53238634 18489729 KAVITA TANGNIYA 1997-04-14 F GEN N 116 6 54210033 18226177 ASHISH MISHRA 1987-01-25 M GEN N 114 7 51629288 18160913 ANIL KUMAR 1991-04-17 M GEN N 114 8 52413386 18359248 MANDEEP KUMAR 1984-08-05 M GEN N 113 9 53402967 18607405 ASHISH LODHI 1991-02-25 M SC N 113 10 53402898 18661423 MUKESH KUMAR MENARIA 1986-08-16 M GEN N 113 11 54113079 18541558 FAZAL KAMROON 1994-08-11 M GEN N 113 12 54005512 18543675 ANSHU SINGH 1981-11-16 F GEN N 112 13 51091077 18076738 HIMANI 1992-03-14 F OBC N 112 14 54209672 18188361 GOVIND YADAV 1994-10-14 M OBC N 112 15 53711605 18897366 NARESHBABU GANDU 1987-08-28 M OBC N 112 16 54210297 18938249 ALOK KUMAR YADAV 1991-12-19 M OBC N 112 17 53235295 181308956 DAYA RAM 1988-08-05 M OBC OH N 112 18 53304623 18509274 ANKITA NAGPAL 1988-07-02 F GEN N 111 19 53807371 18394468 MOHD FIROZ 1993-02-13 M GEN N 111 20 51090613 18630937 SURAJ RAM 1990-08-04 M OBC N 111 21 51085121 18313981 NIKHIL KUMAR 1987-01-28 M GEN N 111 22 54410013 18438640 PIYALI GHOSH 1982-12-25 F GEN N 111 23 51092291 18319209 NEHA TYAGI 1994-09-24 F GEN N 111 24 51629093 18238761 PARVINDER KAUR 1995-12-19 F OBC N -

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

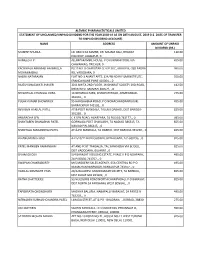

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

Year Book of the Indian National Science Academy

AL SCIEN ON C TI E Y A A N C A N D A E I M D Y N E I A R Year Book B of O The Indian National O Science Academy K 2019 2019 Volume I Angkor, Mob: 9910161199 Angkor, Fellows 2019 i The Year Book 2019 Volume–I S NAL CIEN IO CE T A A C N A N D A E I M D Y N I INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY New Delhi ii The Year Book 2019 © INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY ISSN 0073-6619 E-mail : esoffi [email protected], [email protected] Fax : +91-11-23231095, 23235648 EPABX : +91-11-23221931-23221950 (20 lines) Website : www.insaindia.res.in; www.insa.nic.in (for INSA Journals online) INSA Fellows App: Downloadable from Google Play store Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) Professor Gadadhar Misra, FNA Production Dr VK Arora Shruti Sethi Published by Professor Gadadhar Misra, Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) on behalf of Indian National Science Academy, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002 and printed at Angkor Publishers (P) Ltd., B-66, Sector 6, NOIDA-201301; Tel: 0120-4112238 (O); 9910161199, 9871456571 (M) Fellows 2019 iii CONTENTS Volume–I Page INTRODUCTION ....... v OBJECTIVES ....... vi CALENDAR ....... vii COUNCIL ....... ix PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xi RECENT PAST VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xii SECRETARIAT ....... xiv THE FELLOWSHIP Fellows – 2019 ....... 1 Foreign Fellows – 2019 ....... 154 Pravasi Fellows – 2019 ....... 172 Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 173 Foreign Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 177 Fellowship – Sectional Committeewise ....... 178 Local Chapters and Conveners ...... -

M.Sc. Physics

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI MASTER OF SCIENCE in PHYSICS M. Sc. (Physics) (Effective from Academic Year 2018-19) PROGRAMME BROCHURE M.Sc. (Physics)Revised Syllabus as approved by Academic Council on XXXX, 2018 and Executive Council on YYYY, 2018 i Table of Contents I About the Department 1 II Introduction to CBCS (Choice Based Credit System) 3 II.1 Scope 3 II.2 Definitions 3 III M. Sc. Programme Details 3 III.1 Programme Objectives (POs) 3 III.2 Programme Specific Outcomes (PSOs) 4 III.3 Programme Structure 4 III.4 Eligibility for Admissions 5 III.5 Assessment of Students’ Performance and Scheme of Examination 5 III.6 Pass Percentage & Promotion Criteria 6 III.7 Semester to Semester Progression 6 III.8 Conversion of Marks into Grades 6 III.9 Grade Points 6 III.10 CGPA Calculation 6 III.11 Division of Degree into Classes 6 III.12 Attendance Requirement 6 III.13 Span Period 6 III.14 Guidelines for the Award of Internal Assessment Marks 6 III.15 M. Sc. Programme (Semester Wise) 7 IV Course Wise Content Details for M. Sc. Physics Programme 14 ii I About the Department The Department of Physics & Astrophysics is possibly the largest science department in any Indian university. The “Old Block” of the Department is located in the picturesque Viceroy's complex, and shares space in an elegant pillared building with the Department of Chemistry. Established in 1922, the Department, in its early years was influenced by M. N. Saha and subsequently, by his illustrious student, Padma Bhushan (1964) and Padma Vibhushan (1973) Daulat Singh Kothari, who joined the Department in 1934. -

Meghnad Saha: a Brief History 1 Ajoy Ghatak

A Publication of The National Academy of Sciences India (NASI) Publisher’s note Every possible eff ort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this book is accurate at the time of going to press, and the publisher and authors cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions, however caused. No responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting, or refraining from action, as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by the editors, the publisher or the authors. Every eff ort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material used in this book. Th e authors and the publisher will be grateful for any omission brought to their notice for acknowledgement in the future editions of the book. Copyright © Ajoy Ghatak and Anirban Pathak All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded or otherwise, without the written permission of the editors. First Published 2019 Viva Books Private Limited • 4737/23, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002 Tel. 011-42242200, 23258325, 23283121, Email: [email protected] • 76, Service Industries, Shirvane, Sector 1, Nerul, Navi Mumbai 400 706 Tel. 022-27721273, 27721274, Email: [email protected] • Megh Tower, Old No. 307, New No. 165, Poonamallee High Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600 095 Tel. 044-23780991, 23780992, 23780994, Email: [email protected] • B-103, Jindal Towers, 21/1A/3 Darga Road, Kolkata 700 017 Tel. 033-22816713, Email: [email protected] • 194, First Floor, Subbarama Chetty Road Near Nettkallappa Circle, Basavanagudi, Bengaluru 560 004 Tel. -

Krishnaswamy Kasturirangan Date of Birth 24 October 1940 Place Ernakulum (India) Nomination 21 October 2006 Field Astronomy Title Professor

Krishnaswamy Kasturirangan Date of Birth 24 October 1940 Place Ernakulum (India) Nomination 21 October 2006 Field Astronomy Title Professor Professional address Member Planning Commission R.No.119, Yojana Bhawan Parliament Street New Delhi - 110 001 (India) Most important awards, prizes and academies Awards: Three civilian awards from the Government of India: the Padma Shri (1982), Padma Bhushan (1992) and Padma Vibhushan (2000); Intercosmos Council Award, Soviet Academy of Sciences (1981); Dr. K.R. Ramanathan Memorial Gold Medal, Indian Geo-Physical Union (1995); M.P. Birla Memorial Award in Astronomy (1997); Goyal Award, Goyal Foundation (1997); Biren Roy Memorial Lecture Medal, Indian Physical Society (1998); Shri Murli M. Chugani Memorial Award for Excellence in Applied Physics, Indian Physics Association (1999); H.K. Firodia Award for Excellence in Science & Technology (1999); IGU Millennium Award, Indian Geo-Physical Union (1999); M.N. Saha Birth Centenary Award, 87th Indian Science Congress (2000); Aryabhata Medal Award 2000, Indian National Science Academy (2001); 4th Sri Chandrasekarendra Saraswati National Eminence Award, South Indian Education Society (2001), International Collaboration Accomplishment Award, International Society for Air Breathing Engines (2001); Officer of the Légion d'honneur, France (2002); Rathindra Puraskar by Visva Bharati, Shantiniketan (2002); V. Krishnamurthy Award for Excellence, Centre for Organisation Development (2002); G.M. Modi Award for outstanding contribution in innovative Science, Gujarmal Modi Science Foundation (2002); Bhoovigyan Ratna Award, Bhoovigyan Vikas Foundation (2002); 8th National Science & Technology Award for Excellence, Jeppiaar Educational Trust (2003); 6th Ram Mohan Puraskar, Ram Mohan Mission (2003); Ashustosh Mukerjee Gold Medal, Indian Science Congress Association (2004); Lifetime Contribution Award in Engineering, Indian National Academy of Engineering (2004); Prof. -

A Tribute Professor Krishnaji (January 13, 1922 — August 14, 1997)

iv A Tribute Professor Krishnaji (January 13, 1922 — August 14, 1997) Edited by Govindjee Urbana, Illinois, USA and Shyam Lal Srivastava Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, India i The Cover A photograph of Krishnaji (Dada), 1980 Editors Govindjee, the youngest brother of Krishnaji, lives at 2401 South Boudreau, Urbana, Illinois, 61801, USA E-mail: [email protected] Shyam Lal Srivastava, a former doctoral student, and a long time colleague of Krishnaji, lives at 189/129 Allenganj, Allahabad-211002, Uttar Pradesh (UP), India E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved Copyright © 2010 Govindjee No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission of Govindjee or Shyam Lal Srivastava. Printed at Apex Graphics, Buxi Bazar, Allahabad – 211003, India ii Remembering Three Generations of Krishnaji Krishnaji (Dada) (1922 – 1997) Bimla (Bhabhi) (1927 – 2007) Deepak (1949 – 2008) Ranjan (1952 – 1992) Manju (1954 – 1986) Neera (1973 – 1988) Rajya Ashish (1983 – 1986) Rajya Vishesh (1985 – 1986) iii iv Preface he primary goal of this book is to pay tribute to Professor T Krishnaji, who we call Dada. He was a great human being, a friend to the young and the old, a visionary teacher, a remarkable scientist, an institution builder, an academician, and an excellent and effective administrator. And, at the same time, he was a loving and loyal son, a loving brother, a loving husband, a loving father, and a loving grandfather. A second and equally important goal of this book is to present his life and that of his dear wife Bimla Asthana (Bhabhi to one of us, Govindjee (G), and Jiya to the other, Shyam Lal Srivastava) to his extended family, friends, relatives, students and professional scientists around the World.