Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WDSG Keeping in Touch Newsletter, Issue 9

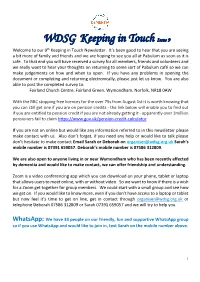

WDSG Keeping in Touch Issue 9 Welcome to our 9th Keeping in Touch Newsletter. It’s been good to hear that you are seeing a bit more of family and friends and we are hoping to see you all at Pabulum as soon as it is safe. To that end you will have received a survey for all members, friends and volunteers and we really want to hear your thoughts on returning to some sort of Pabulum café so we can make judgements on how and when to open. If you have any problems in opening the document or completing and returning electronically, please just let us know. You are also able to post the completed survey to: Fairland Church Centre, Fairland Green, Wymondham, Norfolk, NR18 0AW With the BBC stopping free licences for the over 75s from August 1st it is worth knowing that you can still get one if you are on pension credits - the link below will enable you to find out if you are entitled to pension credit if you are not already getting it - apparently over 1million pensioners fail to claim https://www.gov.uk/pension-credit-calculator If you are not on online but would like any information referred to in this newsletter please make contact with us. Also don’t forget, if you need any help or would like to talk please don’t hesitate to make contact Email Sarah or Deborah on [email protected] Sarah’s mobile number is 07391 659057. Deborah’s mobile number is 07586 312809. We are also open to anyone living in or near Wymondham who has been recently affected by dementia and would like to make contact, we can offer friendship and understanding. -

Statistical Yearbook 2019

STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2019 Welcome to the 2019 BFI Statistical Yearbook. Compiled by the Research and Statistics Unit, this Yearbook presents the most comprehensive picture of film in the UK and the performance of British films abroad during 2018. This publication is one of the ways the BFI delivers on its commitment to evidence-based policy for film. We hope you enjoy this Yearbook and find it useful. 3 The BFI is the lead organisation for film in the UK. Founded in 1933, it is a registered charity governed by Royal Charter. In 2011, it was given additional responsibilities, becoming a Government arm’s-length body and distributor of Lottery funds for film, widening its strategic focus. The BFI now combines a cultural, creative and industrial role. The role brings together activities including the BFI National Archive, distribution, cultural programming, publishing and festivals with Lottery investment for film production, distribution, education, audience development, and market intelligence and research. The BFI Board of Governors is chaired by Josh Berger. We want to ensure that there are no barriers to accessing our publications. If you, or someone you know, would like a large print version of this report, please contact: Research and Statistics Unit British Film Institute 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN Email: [email protected] T: +44 (0)20 7173 3248 www.bfi.org.uk/statistics The British Film Institute is registered in England as a charity, number 287780. Registered address: 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN 4 Contents Film at the cinema -

Pressreader Magazine Titles

PRESSREADER: UK MAGAZINE TITLES www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader Computers & Technology Sport & Fitness Arts & Crafts Motoring Android Advisor 220 Triathlon Magazine Amateur Photographer Autocar 110% Gaming Athletics Weekly Cardmaking & Papercraft Auto Express 3D World Bike Cross Stitch Crazy Autosport Computer Active Bikes etc Cross Stitch Gold BBC Top Gear Magazine Computer Arts Bow International Cross Stitcher Car Computer Music Boxing News Digital Camera World Car Mechanics Computer Shopper Carve Digital SLR Photography Classic & Sports Car Custom PC Classic Dirt Bike Digital Photographer Classic Bike Edge Classic Trial Love Knitting for Baby Classic Car weekly iCreate Cycling Plus Love Patchwork & Quilting Classic Cars Imagine FX Cycling Weekly Mollie Makes Classic Ford iPad & Phone User Cyclist N-Photo Classics Monthly Linux Format Four Four Two Papercraft Inspirations Classic Trial Mac Format Golf Monthly Photo Plus Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Mac Life Golf World Practical Photography Classic Racer Macworld Health & Fitness Simply Crochet Evo Maximum PC Horse & Hound Simply Knitting F1 Racing Net Magazine Late Tackle Football Magazine Simply Sewing Fast Bikes PC Advisor Match of the Day The Knitter Fast Car PC Gamer Men’s Health The Simple Things Fast Ford PC Pro Motorcycle Sport & Leisure Today’s Quilter Japanese Performance PlayStation Official Magazine Motor Sport News Wallpaper Land Rover Monthly Retro Gamer Mountain Biking UK World of Cross Stitching MCN Stuff ProCycling Mini Magazine T3 Rugby World More Bikes Tech Advisor -

Revue Française De Civilisation Britannique, XXVI-1 | 2021 Rhoda Power, BBC Radio, and Mass Education, 1922-1957 2

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XXVI-1 | 2021 The BBC and Public Service Broadcasting in the Twentieth Century Rhoda Power, BBC Radio, and Mass Education, 1922-1957 Rhoda Power, la radio de BBC, et l’education universelle, 1922-1957 Laura Carter Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/7316 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.7316 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Electronic reference Laura Carter, “Rhoda Power, BBC Radio, and Mass Education, 1922-1957”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XXVI-1 | 2021, Online since 05 December 2020, connection on 05 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/7316 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb.7316 This text was automatically generated on 5 January 2021. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Rhoda Power, BBC Radio, and Mass Education, 1922-1957 1 Rhoda Power, BBC Radio, and Mass Education, 1922-1957 Rhoda Power, la radio de BBC, et l’education universelle, 1922-1957 Laura Carter AUTHOR'S NOTE I would like to thank Peter Mandler and Rozemarijn van de Wal for supporting and advising me on the research behind this article, and Louise North of the BBC Written Archives Centre and the anonymous reviewer for this journal for their help in the preparation of this article. The BBC copyright content reproduced in this article is courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved. -

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter Lebanon (2009) he timeless figure of the raw recruit overpowered by the shock of battle first attracted the full gaze of literary attention in Crane’s Red Badge of Courage (1894- T 95). Generations of Americans eventually came to recognize Private Henry Fleming as the key fictional image of a young American soldier: confused, unprepared, and pretty much alone. But despite Crane’s pervasive ironies and his successful refutation of genteel literary treatments of warfare, The Red Badge can nonetheless be read as endorsing battle as a ticket to manhood and self-confidence. Not so the First World War verse of Lieutenant Wilfred Owen. Owen’s antiheroic, almost revolutionary poems introduced an enduring new archetype: the young soldier as a guileless victim, meaninglessly sacrificed to the vanity of civilians and politicians. Written, though not published during the war, Owen’s “Strange Meeting,” “The Parable of the Old Man and the Young,” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” especially, exemplify his judgment. Owen, a decorated officer who once described himself as a “pacifist with a very seared conscience,” portrays soldiers as young, helpless, innocent, and ill- starred. On the German side, the same theme pervades novelist Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1928): Lewis Milestone’s film adaptation (1930) is often ranked among the best war movies of all time. Unlike Crane, neither Owen nor Remarque detected in warfare any redeeming value; and by the late twentieth century, general revulsion of the educated against war solicited a wide acceptance of this sympathetic image among Western War, Literature & the Arts: an international journal of the humanities / Volume 32 / 2020 civilians—incomplete and sentimental as it is. -

Fawlty Towers - Episode Guide

Performances October 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15 Three episodes of the classic TV series are brought to life on stage. Written by John Cleese & Connie Booth. Music by Dennis Wilson By Special Arrangement With Samuel French and Origin Theatrical Auditions Saturday June 18, Sunday June 19 Thurgoona Community Centre 10 Kosciuszko Road, Thurgoona NSW 2640 Director: Alex 0410 933 582 FAWLTY TOWERS - EPISODE GUIDE ACT ONE – THE GERMANS Sybil is in hospital for her ingrowing toenail. “Perhaps they'll have it mounted for me,” mutters Basil as he tries to cope during her absence. The fire-drill ends in chaos with Basil knocked out by the moose’s head in the lobby. The deranged host then encounters the Germans and tells them the “truth” about their Fatherland… ACT TWO – COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS It’s not a wise man who entrusts his furtive winnings on the horses to an absent-minded geriatric Major, but Basil was never known for that quality. Parting with those ill-gotten gains was Basil’s first mistake; his second was to tangle with the intermittently deaf Mrs Richards. ACT THREE – WALDORF SALAD Mine host's penny-pinching catches up with him as an American guest demands the quality of service not normally associated with the “Torquay Riviera”, as Basil calls his neck of the woods. A Waldorf Salad is not part of Fawlty Towers' standard culinary repertoire, nor is a Screwdriver to be found on the hotel's drinks list… FAWLTY TOWERS – THE REGULARS BASIL FAWLTY (John Cleese) The hotel manager from hell, Basil seems convinced that Fawlty Towers would be a top-rate establishment, if only he didn't have to bother with the guests. -

The Underground War on the Western Front in WWI. Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 9 (3)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications nn Banks, I. (2014) Digging in the dark: the underground war on the Western Front in WWI. Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 9 (3). pp. 156-178. Copyright © 2014 W. S. Maney & Son Ltd A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/102030/ Deposited on: 29 January 2015 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Digging in the Dark: The Underground War on the Western Front in WWI Iain Banks Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK Abstract Throughout the First World War, with the trenches largely static, the combatants tried to break the deadlock by tunnelling under one another’s trenches. The Tunnelling Companies of the British Royal Engineers were engaged in a bitter struggle against German Pioneers that left both sides with heavy casualties. A project to determine the location of one particular act of heroism in that underground war has resulted in the erection of a monument to the Tunnellers at Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée in northern France. Keywords: Tunnelling Companies; Royal Engineers; William Hackett; Tunnellers’ Memorial; mine warfare Introduction The war that raged from 1914 to 1918 is characterised in the popular imagination in terms of trenches, mud and shellfire. -

The Lost Legions of Fromelles PDF Book

THE LOST LEGIONS OF FROMELLES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Barton | 448 pages | 17 Jul 2014 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781472117120 | English | London, United Kingdom The Lost Legions of Fromelles PDF Book In this book, he has given us a detailed, impassioned and arresting account of a bloody day on the Western Front, one that resonates more loudly now than for many years. He describes its long and surprising genesis, and offers an unexpected account of the The action at Fromelles in July is Australia's most catastrophic military failure. AUS NZ. Fromelles remains controversial, not least because in recovering the remains the authorities acceded to requests that they try to identify individual corpses. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Stone Cold Andrew Faulkner. Be Curious — Leeds, Leeds. Kindle Edition , pages. O n one of those smudgy French days when the mist clings close to the damp earth until well after lunch, I sat in a little estaminet in Fromelles that is famously festooned with boxing kangaroos and Australian flags. Threads collapsed expanded unthreaded. Fromelles has attracted a fair amount of attention since , when the existence of mass graves was confirmed at Pheasant Wood, but no recent previous account has paid so much attention to both the detail and the context based on a very wide reading of the available sources, British, Australian and, most crucially, Bavarian. His other books include The Somme, and Passchendaele. I found this book very interesting and very sad. Horrie the War Dog Roland Perry. Clain Jaques rated it really liked it Mar 06, Want to Read saving…. -

History on Television Bell, Erin; Gray, Ann

www.ssoar.info History on television Bell, Erin; Gray, Ann Postprint / Postprint Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: www.peerproject.eu Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bell, E., & Gray, A. (2007). History on television. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 10(1), 113-133. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1367549407072973 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter dem "PEER Licence Agreement zur This document is made available under the "PEER Licence Verfügung" gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zum PEER-Projekt finden Agreement ". For more Information regarding the PEER-project Sie hier: http://www.peerproject.eu Gewährt wird ein nicht see: http://www.peerproject.eu This document is solely intended exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und beschränktes for your personal, non-commercial use.All of the copies of Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument this documents must retain all copyright information and other ist ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to alter Gebrauch bestimmt. Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute auf gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses or otherwise use the document in public. Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke conditions of use. vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts

JANUARY 2019 MARLINA THE MURDERER IN FOUR ACTS “velveteen glamour and brilliant programming...” (The Guardian) “possibly Britain’s most beautiful cinema..” (BBC) JANUARY 2019 • ISSUE 166 www.therexberkhamsted.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6.30pm Sun 4.30-5.30pm All-embracing, inclusive, diverse, International. More to come from somewhere else… ith no time for no doubt continue to be. posing as arty, So we will pro-actively go Wholy or worthy, we out and find them. These are are netting the best and most to be included in among the interesting new films from general popular releases, Europe and other countries which will also include CONTENTS throughout the year now documentaries and other there are more available to us interesting independent Films At A Glance 16-17 than has been for months. releases. So watch out for Rants & Pants 27 We will continue this until them and come. You will they dry up again. We are be surprised BOX OFFICE: 01442 877759 aware to have severely how diverse, neglected world cinema in exciting and Mon to Sat 10.30-6.30 2018, purely because the beautiful they Sun 4.30-5.30 releases available to us in the are, even the UK have been scarce and will brutal ones. SEAT PRICES Circle £9.50 FILMS OF THE MONTH Concessions/ABL £8.00 Back Row £8.00 Table £11.50 Concessions/ABL £10.00 Royal Box Seat (Seats 6) £13.00 Whole Royal Box £73.00 Matinees - Upstairs £5, Downstairs £6.50, Royal Box £10 Disabled and flat access: through the gate on High Street (right of apartments) Shoplifters (Japan) Dogman (Italy) Mon 7th 7.30pm, Tue 8th 2pm Mon 14th 7.30pm See page 13 See page 18 Director: James Hannaway 01442 877999 Advertising: Chloe Butler THE FOOD AND DRINK AND 01442 877999 Artwork: Demiurge Design ROCK AND ROLL TOUR 01296 668739 The Rex Tickets on sale 1 February. -

Ethical Fashion

KS2 On The Move Thematic Unit Introduction to Thematic Unit This ICL looks at movement from a very broad perspective. It is mainly based in the subject area of The World Around Us exploring all the strands of History, Geography and Science and Technology. There are also opportunities to explore aspects of Personal Development and Mutual Understanding. In The World Around Us pupils are encouraged to explore the concepts of Interdependence, Place, Movement and Energy and Change Over Time. This unit most obviously addresses Movement and Energy but the other aspects also feature as well. The Key Questions in this unit ask: What makes animals move? … focusing on animal migration and in particular those animals who migrate to and from Northern Ireland. How do we move? … focusing on the biology of human movement – muscles and bones working together. What makes people travel? … taking a look at large scale movements of people now and in the past – invaders, those who left Ireland during the famine and new arrivals in Northern Ireland today. This section links with Personal Development and Mutual Understanding. How do we travel, now and in the past? … looks at different methods of transport and how they have changed over time. How do water, light and energy travel? How do forces affect movement? What is ‘green energy? … looks at the physics behind movement and at the rules for how light and sound travel. Consolidating the Learning in this unit This ICL draws on a huge amount of material as the subject of movement touches on almost every aspect of the World Around Us. -

(OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (Inside) Interior Design

Publication Magazine Genre Frequency Language $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (inside) interior design review Art & Photo English Bimonthly .