Learning from Atlantic Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

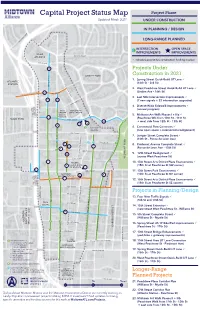

Capital Project Status Map Project Phase Updated March 2021 UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Capital Project Status Map Project Phase Updated March 2021 UNDER CONSTRUCTION IN PLANNING / DESIGN LONG-RANGE PLANNED Deering Road INTERSECTION OPEN SPACE IMPROVEMENTS IMPROVEMENTS SCAD Beverly Road ATLANTA indicates project has construction funding in place 19th Street 16 Projects Under ANSLEY PARK Construction in 2021 1. Spring Street Quick-Build LIT Lane ATLANTIC (16th St - 3rd St) STATION Peachtree Street Spring Street 2. West Peachtree Street Quick-Build LIT Lane (Linden Ave - 16th St) 22 17th Street 3. Last Mile Intersection Improvements 19 20 (7 new signals + 23 intersection upgrades) 16th Street 4. District-Wide Sidewalk Improvements ARTS WOODRUFF (annual program) Williams Street CENTER ARTS CENTER MARTA 5. Midtown Art Walk Phases I + IIIa 14 STATION HOME PARK (Peachtree Wlk from 10th St - 11th St 15th Street 3 18 + west side from 12th St - 13th St) 10 12 2 3 COLONY 6. Commercial Row Commons SQUARE (new open space + intersection realignment) 14th Street 7. Juniper Street Complete Street (14th St - Ponce de Leon Ave) 13 13 13 13th Street 3 5 8. Piedmont Avenue Complete Street West Peachtree Street Peachtree West 23 7 9 (Ponce de Leon Ave - 15th St) 12th Street Crescent Avenue 23 9. 12th Street Realignment (across West Peachtree St) 11th Street PIEDMONT PARK 1 FEDERAL 10. 15th Street Arts District Plaza Enancements 5 RESERVE BANK (15th St at Peachtree St SW corner) OF ATLANTA 11 17 10th Street 11. 10th Street Park Enancements MIDTOWN 8 (10th St at Peachtree St NE corner) MARTA STATION 6 3 21 Peachtree Place 12. 15th Street Arts District Plaza Enancements (15th St at Peachtree St SE corner) 8th Street Projects in Planning/Design 7th Street Williams Street 13. -

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF of RETAIL AVAILABLE

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF OF RETAIL AVAILABLE LOCATED IN THE HEART OF 12TH AND MIDTOWN A premier apartment high rise building with a WELL POSITIONED RETAIL OPPORTUNITY Surrounded by Atlanta’s Highly affluent market, with Restaurant and retail vibrant commercial area median annual household opportunities available incomes over $74,801, and median net worth 330 Luxury apartment 596,000 SF Building $58 Million Project units. 476 parking spaces SITE PLAN - PHASE 4A / SUITE 3 / 1,861 SF* SITE PLAN 12th S TREET SUITERETAIL 1 RETAIL SUITERETAIL 3 RESIDENTIAL RETAIL RETAIL 1 2 3 LOBBY 4 5 2,423 SF 1,8611,861 SFSF SUITERETAIL 6A 3,6146 A SF Do Not Distrub Tenant E VENU RETAIL A 6 B SERVICE LOADING S C E N T DOCK SUITERETAIL 7 E 3,622 7 SF RETAIL PARKING CR COMPONENT N S I T E P L AN O F T H E RET AIL COMP ONENT ( P H ASE 4 A @ 77 12T H S TREE T ) COME JOIN THE AREA’S 1 2 TGREATH & MID OPERATORS:T O W N C 2013 THIS DRAWING IS THE PROPERTY OF RULE JOY TRAMMELL + RUBIO, LLC. ARCHITECTURE + INTERIOR DESIGN AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT WRITTEN CONSENT A TLANT A, GEOR G I A COMMISSI O N N O . 08-028.01 M A Y 28, 2 0 1 3 L:\06-040.01 12th & Midtown Master Plan\PRESENTATION\2011-03-08 Leasing Master Plan *All square footages are approximate until verified. THE MIDTOWN MARKET OVERVIEW A Mecca for INSPIRING THE CREATIVE CLASS and a Nexus for TECHNOLOGY + INNOVATION MORE THAN ONLY 3 BLOCKS AWAY FROM 3,000 EVENTS ANNUALLY PIEDMONT PARK • Atlanta Dogwood Festival, • Festival Peachtree Latino THAT BRING IN an arts and crafts fair • Music Midtown & • The finish line of the Peachtree Music Festival Peachtree Road Race • Atlanta Pride Festival & 6.5M VISITORS • Atlanta Arts Festival Out on Film 8 OF 10 ATLANTA’S “HEART OF THE ARTS”DISTRICT ATLANTA’S LARGEST LAW FIRMS • High Museum • ASO • Woodruff Arts Center • Atlanta Ballet 74% • MODA • Alliance Theater HOLD A BACHELORS DEGREE • SCAD Theater • Botanical Gardens SURROUNDED BY ATLANTA’S TOP EMPLOYERS R. -

Commercial Real Estate

COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE URBAN LAND INSTITUTE October 5-11, 2012 SPECIAL SECTION Page 25A Tapping resouces TAP teams wrestle development challenges By Martin Sinderman CONTRIBUTING WRITER roups dealing these communities come up with there are some projects done on a recommendations regarding development with real estate timely solutions.” pro bono basis. packages that identify the sites, program, development-related Potential TAP clients set things in motion The past year was a busy one for the expected goals, financing/ funding mecha- problems can tap by contacting the ULI Atlanta office. Once TAP program, Callahan reported, with a nisms, and other incentives to attract into an increasingly they are cleared for TAP treatment, they total of six TAPs undertaken. developers. popular source of receive the services of a ULI panel of These included one TAP where the The LCI study in Morrow dealt with assistance from subject-matter experts in fields such as Fulton Industrial Boulevard Community ideas regarding redevelopment of proper- the Urban Land development, urban design, city planning, Improvement District (CID) worked with ties that had been vacated by retailers over Institute. and/or other disciplines that deal with ULI Atlanta to obtain advice and the years, according to city of Morrow ULI’s Technical Assistance Program, commercial retail, office, industrial, recommendations on the revitalization Planning & Economic Development G or TAP, provides what it describes as residential and mixed land uses. and improved economic competitiveness -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

Blueprint Midtown 3. ACTION PLAN Introduction

Blueprint Midtown 3. ACTION PLAN Introduction This document identifies Midtown’s goals, implementation strategies and specific action items that will ensure a rich diversity of land uses, vibrant street-level activity, quality building design, multimodal transportation accessibility and mobility, and engaging public spaces. Blueprint Midtown 3.0 is the most recent evolution of Midtown Alliance’s community driven plan that builds on Midtown’s fundamental strengths and makes strategic improvements to move the District from great to exceptional. It identifies both high priority projects that will be advanced in the next 10 years, as well as longer-term projects and initiatives that may take decades to achieve but require exploration now. Since 1997, policies laid out in Blueprint Midtown have guided public and private investment to create a clean, safe, and vibrant urban environment. The original plan established a community vision for Midtown that largely remains the same: a livable, walkable district in the heart of Atlanta; a place where people, business and culture converge to create a live-work-play community with a distinctive personality and a premium quality of life. Blueprint Midtown 3.0 builds on recent successes, incorporates previously completed studies and corridor plans, draws inspiration from other places and refines site-specific recommendations to reflect the changes that have occurred in the community since the original unveiling of Blueprint Midtown. Extensive community input conducted in 2016 involving more than 6,000 Midtown employers, property owners, residents, workers, visitors, public-sector partners, and subject-matter experts validates the Blueprint Midtown vision for an authentic urban experience. The Action Plan lives with a family of Blueprint Midtown 3.0 documents which also includes: Overview: Moving Forward with Blueprint Midtown 3.0, Midtown Character Areas Concept Plans (coming soon), Appendices: Project Plans and 5-Year Work Plan (coming soon). -

2. Hotel Information 3. Room Information 4. Deposit

The Atlanta International DEADLINE: Tuesday, November 15, 2016 Gift & Home Furnishings Market® Only one room request per form please. Make additional copies if necessary. SHOWROOMS To make a reservation, please fax form to Tara Yorke at January 10 – 17, 2017 678.686.5287 or email [email protected]. TEMPORARIES Note: Retailers are only eligible to participate in one promotion. January 12 – 16, 2017 Confirmations will be sent via email from [email protected]. Hotel availability is based on a first come, first served basis and therefore not guaranteed. ( ) 1. CONTACT INFORMATION REQUIRED STORE/COMPANY NAME CUSTOMER NAME STREET ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP POSTAL CODE EMAIL PHONE LAST SHOW ATTENDED AT AMERICASMART (if applicable) STORE TYPE 2. HOTEL INFORMATION Rank three hotel choices from the list provided. ARRIVAL DATE 1. 2. DEPARTURE DATE 3. 3. ROOM INFORMATION Please supply names of all persons to occupy room and Room Type: type of room. Single Dbl (2ppl/1bed) Dbl/DBL (2ppl/2beds) King-size bed SPECIAL REQUESTS I am in need of an ADA accessible room. I may need special assistance from the hotel in the event of an emergency. Note: room type & special requests based on availability at check-in. Other, please list: 4. DEPOSIT INFORMATION: Reservations will NOT be processed without a credit card guarantee. The hotel reserves the right to charge a deposit of one night’s room and tax. (GA 16% tax). Please read through all cancellation policies in your confirmation email. CREDIT CARD NUMBER TYPE EXPIRATION DATE (after July 2016) ✗ NAME (printed) SIGNATURE FOR AMC Confirmation Number: USE ONLY #NSAMC: 1 NT BG PPP TY OFFICIAL HOTELS & RATES The Atlanta International Gift & Home Furnishings Market Permanent Showrooms: Tuesday, January 12 – Tuesday, January 19, 2017 Temporaries: Thursday, January 14 – Monday, January 18, 2017 The Atlanta International Area Rug Market Permanent: Wednesday, January 13 – Saturday, January 16, 2017 Temporaries: Wednesday, January 13 – Saturday, January 16, 2017 AmericasMart, Bldg. -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

Piedmont Hospital Achieves US News and World Report

Piedmont Hospital Achieves U.S. News and World Report Rankings Summer/Fall 2011 PIEDMONT Volume 21, No. 3 A publication of Piedmont Healthcare Confronting Cancer: Journeys of Support & Healing Also Inside: Non-surgical Alternative to Open-Heart Surgery Hypothermia Technique Saves Rockdale Heart Patient PIEDMONT Letter from the CEO A quick fix. It’s what patients who come through our doors hope our doctors and nurses have for what ails PIEDMONT HEALTHCARE them. Sometimes the cure is a quick fix. Often, it is not. Chairman of the Board: William A. Blincoe, M.D. The same hope is true for those of us who work in Foundation Board Chair: Bertram “Bert” L. Levy healthcare. We would like to believe there is a quick President & CEO: R. Timothy Stack fix for what ails many hospitals around the country – namely, the economy and the future under healthcare PIEDMONT HOSPITAL reform. Piedmont Healthcare, along with its hospitals Chairman of the Board: Patrick M. Battey, M.D. and physician groups, is no exception. We are facing President & CEO: Les A. Donahue significant challenges that have caused us to take a proactive approach to ensure our financial stability now and in the future. PIEDMONT FAYETTE HOSPITAL As you know, financial hardships have caused many people to put their Chairman of the Board: James C. Sams, M.D. healthcare needs on hold. Some choose not to see the doctor or have an elective President & CEO: W. Darrell Cutts procedure because they would rather save the copay and the dollars they would spend on what’s not covered. -

Brian Leary Joined Crescent Communities As President of Its Commercial and Mixed-Use Business Unit in 2014

BRIAN LEARY, President, Commerical and Mixed-Use Brian Leary joined Crescent Communities as president of its commercial and mixed-use business unit in 2014. In this role, he directs the company's commercial and mixed-use developments across the country with an active investment and develop- ment portfolio in excess of 3 million square feet. Through Brian's 22 years of experi- ence in real estate, he's overseen an excess of $3.5B in development. Prior to joining Crescent, Brian held senior management positions with Jacoby Devel- opment, Inc., Atlanta Beltline, Inc., AIG Global Real Estate, Atlantic Station, LLC and Central Atlanta Progress. As the managing director of Jacoby Development, a national developer of corporate, mixed-use and retail projects, he launched ONE Daytona, a 4.5-million square foot joint venture with International Speedway Corp. Previously Brian served as president and CEO of Atlanta Beltline, Inc., ‐ the organization execut- ing the implementation of the BeltLine, one of the largest, most wide-ranging urban redevelopment projects in the United States. When complete, the $3B+ project will provide a network of public parks, multi-use trails, transit, public art and thousands of units of housing along a historic 22-mile railroad corridor circling Atlanta. While vice president of AIG Global Real Estate, he oversaw the design and develop- ment of Atlantic Station, a 13.5-million square foot joint venture that, at the time, rep- resented the largest urban brownfield redevelopment in the United States and current- ly includes approximately 1.5 million square feet of retail, 1.5 million square feet of LEED-certified Class-A oce, 3,000 residential units and a 120-room hotel. -

Identifying Atlanta: John Portman, Postmodernism, and Pop-Culture" (2017)

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Identifying Atlanta: John Portman, Postmodernism, and Pop- Culture August McIntyre Dine Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dine, August McIntyre, "Identifying Atlanta: John Portman, Postmodernism, and Pop-Culture" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 128. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/128 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Identifying Atlanta: John Portman, Postmodernism, and Pop Culture Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by August Dine Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2016 Acknowledgements Thanks to my advisor, Pete L’Official; my friends; and my family. Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………….…………………1 Chapter 1: Two Atlantas………………………………………………………….………………4 Chapter 2: The Peachtree Center…..…………………………...………………………………..23 Chapter 3: Pop Culture…………………………..……………………………………………....33 1 Introduction In his 1995 text “Atlanta,” architect, theorist, and notorious provocateur1 Rem Koolhaas claims, “Atlanta has culture, or at least it has a Richard Meier Museum.”2 Koolhaas is implying that the collection at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art is a cultural veneer. -

A Vibrant Retail Opportunity in the Heart of Downtown Atlanta

A VIBRANT RETAIL OPPORTUNITY IN THE HEART OF DOWNTOWN ATLANTA PEACHTREECENTER.COM AN ICON REBORN IT’S BEEN AN ICONIC DOWNTOWN DESTINATION DISTRICT FOR NEARLY 50 YEARS. 6 2.3 50 3 OFFICE MILLION RESTAURANTS ON-SITE BUILDINGS SQUARE FEET & RETAIL HOTELS 2 DOWNTOWN A $14 Billion economic impact from tourism activity ATLANTA in Downtown Atlanta in 2014. 2015 MARKET HIGHLIGHTS 5.2 MILLION 14,491 TOURISTS SURROUNDING HOTEL ROOMS 2.1 MILLION 139,000+ CONVENTIONEERS DAYTIME EMPLOYEES 20.4 MILLION 15,000 32,000 ATTENDEES AT ATTRACTIONS, RESIDENTS STUDENTS SPORTING EVENTS AND CONCERTS 3 DOWNTOWN ATLANTA ALL IN THE MIX 223 CASUAL DINING ESTABLISHMENTS Ranked among Atlanta Business Chronicle’s Top 25 Restaurants in 39 Sales: Hard Rock PLACES FOR COFFEE & DESSERTS Cafe, Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse and Sundial Restaurant, Bar & View. 62 ENTERTAINMENT VENUES Named to Yelp’s Top 100 Places to Eat in 2016: Aviva by Kameel and Gus’s World Famous 43 Fried Chicken FULL-SERVICE RESTAURANTS 4 LEGEND 6 OFFICE RESIDENTIAL RETAIL, OFFICE 1 1 SUNTRUST THE OFFICE (Apartments) & MULTIFAMILY 2 10 2 438 APARTMENT UNITS 191 TOWER UNDER CONSTRUCTION POST CENTENNIAL 4 3 PARK 100 PEACHTREE 3 2 4 FULTON SUPPLY 1 LOFTS ALLEN PLAZA 4 1 5 AMERICASMART 200 EDGEWOOD GEORGIA WORLD ATLANTA FEDERAL CONGRESS CENTER PEACHTREE CENTER CENTER 2.3M SF OFFICE SPACE 5 M CENTENNIAL 6 CITY PLAZA OLYMPIC PARK CENTENNIAL 6 TOWER 2 CENTENNIAL 7 PLAZA GEORGIA PACIFIC 7 TOWER PHILIPS 7 6 STONEWALL LOFTS ARENA 8 3 8 FLATIRON MERCEDES-BENZ BUILDING INTOWN LOFTS 8 12 STADIUM 9 4 LEGACY LOFTS M 10 THE POINT AT 5 GEORGIA STATE WESTSIDE UNIVERSITY 11 VILLAGES AT 3 CASTLEBERRY 12 8 CITY WALK 9 7 11 5 5 PEACHTREE Over 10 million CENTER foot falls annually. -

Downtown Atlanta

the green line downtown atlanta Central Atlanta Progress Atlanta Downtown Improvement District 1 the green line / downtown atlanta CENTENNIAL GWCC - C OLYMPIC PARK GWCC - B CONTEXT GWCC - A CNN CENTER GEORGIA DOME INTERNATIONAL PLAZA PHILIPS ARENA DOME/CNN/GWCC MARTA STATION STUDY AREA (Approx. 94 Ac) FIVE POINTS MARTA STATION RUSSELL FEDERAL BLDG GSU MARTA STATION STATE ATLANTA COCAPITOL CITY HALL 2 the green line / downtown atlanta GOALS DOME/CNN/GWCC MARTA STATION FIVE POINTS MARTA STATION GA STATE MARTA STATION GOALS Create an implementable plan that ~ Envisions an iconic destination ~ Stitches the city together through public space, transit and daily life ~ Fosters public and private investment 3 the green line / downtown atlanta CNN CENTER 1. Multimodal passenger terminal built INTERNATIONAL with terminal entrance at viaduct level PHILIPS ARENA PLAZA and transit connections below 2. Railroad Gulch – subdivided by new streets at viaduct level– creating DOME/CNN/GWCC AJC MARTA STATION development sites 3 STATE BAR BUILDING 4 3. New retail, entertainment, hotel uses 2 expand activity of GWCC / GA Dome / 6 Philips Arena 4. New office space takes advantage of HUD 1 enhanced regional transit connection 5. New and improved access to MARTA rail stations 5 6. New triangular park space can be FIVE POINTS MARTA STATION closed to vehicular traffic to host special events and festivals RUSSELL FEDERAL BLDG KEY MAP Typical retail storefronts at viaduct level Atlantic Station – example of new streets to create future development sites 4 the green line / downtown atlanta 1. Transformed Five Points station structure with new platform access and programmed plaza 2.