The Case of Rolls-Royce William Lazonick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION the BMW Group Is a Manufacturer of Luxury Automobiles and Motorcycles

Marketing Activities Of BMW INTRODUCTION The BMW Group is a manufacturer of luxury automobiles and motorcycles. It has 24 production facilities spread over thirteen countries and the company‟s products are sold in more than 140 countries. BMW Group owns three brands namely BMW, MINI and Rolls- Royce. This project contains detailed information about the marketing and promotional activities of BMW. It contains the history of BMW, its evolution after the world war and its growth as one of the leading automobile brands. This project also contains the information about the growth of BMW as a brand in India and its awards and recognitions that it received in India and how it became the market leader. This project also contains the launch of the mini cooper showroom in India and also the information about the establishment of the first Aston martin showroom in India, both owned by infinity cars. It contains information about infinity cars as a BMW dealership and the success stories of the owners. Apart from this, information about the major events and activities are also mentioned in the project, the 3 series launch which was a major event has also been covered in the project. The two project reports that I had prepared for the company are also a part of this project, The referral program project which is an innovative marketing technique to get more customers is a part of this project and the other project report is about the competitor analysis which contains the marketing and promotional activities of the competitors of BMW like Audi, Mercedes and JLR About BMW BMW (Bavarian Motor Works) is a German automobile, motorcycle and engine manufacturing company founded in 1917. -

Ivchenko Progress

® AdvancedAdvanced turboprop,turboprop, propfanpropfan andand turbojetturbojet bypassbypass enginesengines forfor GAGA andand lightlight airplanesairplanes S. DMYTRIYEV 23.11.09 ® HISTORY ZAPOROZHYE MACHINE-BUILDING DESIGN BUREAU PROGRESS STATE ENTERPRISE NAMED AFTER ACADEMICIAN A.G. IVCHENKO (SE IVCHENKO-PROGRESS) Foundation date: May 5, 1945 Over a whole past period, engine manufacturing plants have produced more than 80 , 000 aircraft gas turbine and piston engines, turbostarters and industrial plants. Today, the engines designed by SE IVCHENKO-PROGRESS power 57 types of flying vehicle in 109 countries. Over the years, SE IVCHENKO-PROGRESS engines logged more than 300 million flight hours. © SE Ivchenko-Progress, 2009 2 ® HISTORY D-27 propfan , ÒV3-117 VÌÀ- SBÌ1 turboprop , D-436 turbofan , AI -22 turbofan , AI -222 turbofan , AI -450 turboshaft , 4-th stage AI -450 turboprop , SPM-21 turbofan Turbofans with high power and thrust : 3- rd stage D-136, D-18Ò Turbofans : AI -25, AI -25ÒË, D-36 2-nd stage APUs: AI -9, AI -9 V Turboprops : AI -20, AI -24 1- st stage APU: AI -8 Piston engines: AI -26 , AI-14, AI-4 © SE Ivchenko-Progress, 2009 3 ® DIRECTIONS OF ACTIVITY CIVIL AVIATION: commercial aircraft and helicopters Ìè-2Ì Àí-140 Àí-14 8 STATE AVIATION : trainers and combat trainers, military transport aircraft and helicopters , multipurpose aircraft ßê-18Ò Àí-70 Ìè-26Ò ßê-130 Áe-200 Àí-124 © SE Ivchenko-Progress, 2009 4 ® THE BASIC SPHERES OF ACTIVITIES DESIGN MANUFACTURE OVERHAUL TEST AND DEVELOPMENT PUTTING IN SERIES PRODUCTION AND IMPROVEMENT OF CONSUMER'S CHARACTERISTICS © SE Ivchenko-Progress, 2009 5 INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION OF ® CERTIFICATION AUTHORITIES Totally 60 certificates of various types European Aviation Safety Agency (Germany) Certificate No. -

Robust Gas Turbine and Airframe System Design in Light of Uncertain

Robust Gas Turbine and Airframe System Design in Light of Uncertain Fuel and CO2 Prices Stephan Langmaak1, James Scanlan2, and András Sóbester3 University of Southampton, Southampton, SO16 7QF, United Kingdom This paper presents a study that numerically investigated which cruise speed the next generation of short-haul aircraft with 150 seats should y at and whether a con- ventional two- or three-shaft turbofan, a geared turbofan, a turboprop, or an open rotor should be employed in order to make the aircraft's direct operating cost robust to uncertain fuel and carbon (CO2) prices in the Year 2030, taking the aircraft pro- ductivity, the passenger value of time, and the modal shift into account. To answer this question, an optimization loop was set up in MATLAB consisting of nine modules covering gas turbine and airframe design and performance, ight and aircraft eet sim- ulation, operating cost, and optimization. If the passenger value of time is included, the most robust aircraft design is powered by geared turbofan engines and cruises at Mach 0.80. If the value of time is ignored, however, then a turboprop aircraft ying at Mach 0.70 is the optimum solution. This demonstrates that the most fuel-ecient option, the open rotor, is not automatically the most cost-ecient solution because of the relatively high engine and airframe costs. 1 Research Engineer, Computational Engineering and Design 2 Professor of Aerospace Design, Computational Engineering and Design, AIAA member 3 Associate Professor in Aircraft Engineering, Computational Engineering and Design, AIAA member 1 I. Introduction A. Background IT takes around 5 years to develop a gas turbine engine, which then usually remains in pro- duction for more than two decades [1, 2]. -

Aerospace Engine Data

AEROSPACE ENGINE DATA Data for some concrete aerospace engines and their craft ................................................................................. 1 Data on rocket-engine types and comparison with large turbofans ................................................................... 1 Data on some large airliner engines ................................................................................................................... 2 Data on other aircraft engines and manufacturers .......................................................................................... 3 In this Appendix common to Aircraft propulsion and Space propulsion, data for thrust, weight, and specific fuel consumption, are presented for some different types of engines (Table 1), with some values of specific impulse and exit speed (Table 2), a plot of Mach number and specific impulse characteristic of different engine types (Fig. 1), and detailed characteristics of some modern turbofan engines, used in large airplanes (Table 3). DATA FOR SOME CONCRETE AEROSPACE ENGINES AND THEIR CRAFT Table 1. Thrust to weight ratio (F/W), for engines and their crafts, at take-off*, specific fuel consumption (TSFC), and initial and final mass of craft (intermediate values appear in [kN] when forces, and in tonnes [t] when masses). Engine Engine TSFC Whole craft Whole craft Whole craft mass, type thrust/weight (g/s)/kN type thrust/weight mini/mfin Trent 900 350/63=5.5 15.5 A380 4×350/5600=0.25 560/330=1.8 cruise 90/63=1.4 cruise 4×90/5000=0.1 CFM56-5A 110/23=4.8 16 -

Pegasus Vectored-Thrust Turbofan Engine

Pegasus Vectored-thrust Turbofan Engine Matador Harrier Sea Harrier AV-8A International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark 24 July 1993 International Air Tattoo '93 RAF Fairford The American Society of Mechanical Engineers I MECH E I NTERNATIONAL H ISTORIC M ECHANICAL E NGINEERING L ANDMARK PEGASUS V ECTORED-THRUST T URBOFAN ENGINE 1960 T HE B RISTOL AERO-ENGINES (ROLLS-R OYCE) PEGASUS ENGINE POWERED THE WORLD'S FIRST PRACTICAL VERTICAL/SHORT-TAKEOFF-AND-LANDING JET AIRCRAFT , THE H AWKER P. 1127 K ESTREL. USING FOUR ROTATABLE NOZZLES, ITS THRUST COULD BE DIRECTED DOWNWARD TO LIFT THE AIRCRAFT, REARWARD FOR WINGBORNE FLIGHT, OR IN BETWEEN TO ENABLE TRANSITION BETWEEN THE TWO FLIGHT REGIMES. T HIS ENGINE, SERIAL NUMBER BS 916, WAS PART OF THE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM AND IS THE EARLIEST KNOWN SURVIVOR. PEGASUS ENGINE REMAIN IN PRODUCTION FOR THE H ARRIER II AIRCRAFT. T HE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF M ECHANICAL ENGINEERS T HE INSTITUTION OF M ECHANICAL ENGINEERS 1993 Evolution of the Pegasus Vectored-thrust Engine Introduction cern resulted in a perceived need trol and stability problems associ- The Pegasus vectored for combat runways for takeoff and ated with the transition from hover thrust engine provides the power landing, and which could, if re- to wing-borne flight. for the first operational vertical quired, be dispersed for operation The concepts examined and short takeoff and landing jet from unprepared and concealed and pursued to full-flight demon- aircraft. The Harrier entered ser- sites. Naval interest focused on a stration included "tail sitting" types vice with the Royal Air Force (RAF) similar objective to enable ship- exemplified by the Convair XFY-1 in 1969, followed by the similar borne combat aircraft to operate and mounted jet engines, while oth- AV-8A with the United States Ma- from helicopter-size platforms and ers used jet augmentation by means rine Corps in 1971. -

August 2019 Shannons Sydney Classic

The Preserve Celebrating lots of anniversaries Alvis Fiat Club Armstrong Siddeley Triumph Herald Mini Jaguar Mk 9 & Jaguar Mk 2 VOLVO Car Club Datsun 240Z Hudson AMC Car Club Bolwell Nagari August 2019 Shannons Sydney Classic President’s Report Your 2019 Committee Executive Committee Terry Thompson OAM President The 2018/2019 year has continued the CMC NSW growth and advocacy of our member- VSWG, RSAC & Govt. ship and the historic/classic vehicle movement in general. The Committee has worked Liaison / AHMF Delegate diligently to catch up with things since the unfortunate passing of our wonder woman Secretary, Ms Julie Williams, in June 2018. Tony De Luca Vice President & SSC I again suggest to ALL clubs that you must have plans in place for succession as our hard working executive members are getting older and nothing is certain in this big bad world Kay De Luca folks. Encourage those younger folks please. Treasurer/SSC/Editor Enough of the doom and gloom huh? Our membership of clubs and hence people in Affiliation Renewals those clubs has grown quickly and I will try to set out some numbers below to give you Karen Symington an idea of the size of our group. Secretary General / SSC Last year’s Shannons Sydney Classic display day at Sydney Motorsport Park was once again a booming success. It never ceases to amaze me how Tony De Luca and Allen General Committee Seymour can fit in all the vehicles when the grounds are finite to a major degree. They Lester Gough are wizards in my opinion but fortunately they do not wear robes and pointed hats. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

2. Afterburners

2. AFTERBURNERS 2.1 Introduction The simple gas turbine cycle can be designed to have good performance characteristics at a particular operating or design point. However, a particu lar engine does not have the capability of producing a good performance for large ranges of thrust, an inflexibility that can lead to problems when the flight program for a particular vehicle is considered. For example, many airplanes require a larger thrust during takeoff and acceleration than they do at a cruise condition. Thus, if the engine is sized for takeoff and has its design point at this condition, the engine will be too large at cruise. The vehicle performance will be penalized at cruise for the poor off-design point operation of the engine components and for the larger weight of the engine. Similar problems arise when supersonic cruise vehicles are considered. The afterburning gas turbine cycle was an early attempt to avoid some of these problems. Afterburners or augmentation devices were first added to aircraft gas turbine engines to increase their thrust during takeoff or brief periods of acceleration and supersonic flight. The devices make use of the fact that, in a gas turbine engine, the maximum gas temperature at the turbine inlet is limited by structural considerations to values less than half the adiabatic flame temperature at the stoichiometric fuel-air ratio. As a result, the gas leaving the turbine contains most of its original concentration of oxygen. This oxygen can be burned with additional fuel in a secondary combustion chamber located downstream of the turbine where temperature constraints are relaxed. -

The New Whittle Laboratory Decarbonising Propulsion and Power

The New Whittle Laboratory Decarbonising Propulsion and Power The impressive work undertaken by the Whittle Laboratory, through the National Centre for Propulsion “and Power project, demonstrates the University’s leadership in addressing the fundamental challenges of climate change. The development of new technologies, allowing us to decarbonise air travel and power generation, will be central to our efforts to create a carbon neutral future. Professor Stephen Toope, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge ” 2 The New Whittle Laboratory Summary Cambridge has a long tradition of excellence in the propulsion and power sectors, which underpin aviation and energy generation. From 1934 to 1937, Frank Whittle studied engineering in Cambridge as a member of Peterhouse. During this time he was able to advance his revolutionary idea for aircraft propulsion and founded ‘Power Jets Ltd’, the company that would go on to develop the jet engine. Prior to this, in 1884 Charles Parsons of St John’s College developed the first practical steam turbine, a technology that today generates more than half of the world’s electrical power.* Over the last 50 years the Whittle Laboratory has built on this heritage, playing a crucial role in shaping the propulsion and power sectors through industry partnerships with Rolls-Royce, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Siemens. The Whittle Laboratory is also the world’s most academically successful propulsion and power research institution, winning nine of the last 13 Gas Turbine Awards, the most prestigious prize in the field, awarded once a year since 1963. Aviation and power generation have brought many benefits – connecting people across the world and providing safe, reliable electricity to billions – but decarbonisation of these sectors is now one of society’s greatest challenges. -

A Supersonic Fan Equipped Variable Cycle Engine for a Mach 2.7 Supersonic Transport

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Applied Engineering and Sciences Scholarship Applied Engineering and Sciences 8-22-1985 A Supersonic Fan Equipped Variable Cycle Engine for a Mach 2.7 Supersonic Transport Theodore S. Tavares University of New Hampshire, Manchester, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/unhmcis_facpub Recommended Citation Tavares, T.S., “A Supersonic Fan Equipped Variable Cycle Engine for a Mach 2.7 Supersonic Transport,” NASA-CR-177141, 1986. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Engineering and Sciences at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Applied Engineering and Sciences Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19860019474 2018-07-25T19:53:49+00:00Z ^4/>*>?/ GAS TURBINE LABORATORY DEPARTMENT OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CAMBRIDGE, MA 02139 A FINAL REPORT ON NASA GRANT NAG-3-697 entitled A SUPERSONIC FAN EQUIPPED VARIABLE CYCLE ENGINE FOR A MACH 2.7 SUPERSONIC TRANSPORT by T. S. Tavares prepared for NASA Lewis Research Center Cleveland, OH 44135 (NASA-CB-177141) A SDPEBSCNIC FAN EQUIPPED N86-28946 VARIABLE CYCLE ENGINE.JOB A MACH 2.? SDPEESONIC TBANSPOBT Final Report (Massachusetts Inst. of Tech.) 107 p Unclas CSCL 21E G3/07 43461 August 22, 1985 A SUPERSONIC FAN EQUIPPED VARIABLE CYCLE ENGINE FOR A HACK 2.7 SUPERSONIC TRANSPORT by Theodore Sean Tavares A SUPERSONIC FAN EQUIPPED VARIABLE CYCLE ENGINE FOR A MACH 2.7 SUPERSONIC TRANSPORT by THEODORE SEAN TAVARES ABSTRACT A design stud/ was carried out to evaluate the concept of a variable cycle turbofan engine with an axially supersonic fan stage as powerplant for a Mach 2.7 supersonic transport. -

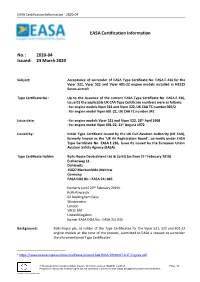

2020-04: Acceptance of Surrender of EASA Type Certificate No. EASA.E.236 for the Viper

EASA Certification Information - 2020-04 EASA Certification Information No.: 2020-04 Issued: 23 March 2020 Subject: Acceptance of surrender of EASA Type Certificate No. EASA.E.236 for the Viper 521, Viper 522 and Viper 601-22 engine models installed in HS125 Series aircraft Type Certificate No.: Up to the issuance of the current EASA Type Certificate No. EASA.E.236, Issue 01 the applicable UK CAA Type Certificate numbers were as follows: - for engine models Viper 521 and Viper 522, UK CAA TC number 029/2 - for engine model Viper 601-22, UK CAA TC number 041 Issue date: - for engine models Viper 521 and Viper 522, 26th April 1968 - for engine model Viper 601-22, 21st August 1972 Issued by: Initial Type Certificate issued by the UK Civil Aviation Authority (UK CAA), formerly known as the ‘UK Air Registration Board’, currently under EASA Type Certificate No. EASA.E.236, Issue 01 issued by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Type Certificate Holder: Rolls-Royce Deutschland Ltd & Co KG (as from 21st February 2019) Eschenweg 11 Dahlewitz 15827 Blankenfelde-Mahlow Germany EASA DOA No.: EASA.21J.065 formerly (until 20th February 2019): Rolls-Royce plc 62 Buckingham Gate Westminster London SW1E 6AT United Kingdom former EASA DOA No.: EASA.21J.035 Background: Rolls-Royce plc, as holder of the Type Certificates for the Viper 521, 522 and 601-22 engine models at the time of the request, submitted to EASA a request to surrender the aforementioned Type Certificates1. 1 https://www.easa.europa.eu/download/easa-product-lists/EASA-PRODUCT-LIST-Engines.pdf © European Union Av iation Safety Agency. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES