How Science Is Unlocking the Secrets of Addiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friday, October 27, 2017 Kaufman Music Center

2017 INTERNATIONAL MENTAL HEALTH RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM Friday, October 27, 2017 9:00am–4:30pm Kaufman Music Center 129 West 67th Street New York, NY 10023 Welcome Welcome to our International Mental Health Nationally recognized for broad expertise in Research Symposium. Today we will hear from education, research, clinical care and health the Foundation’s 2017 Outstanding Achieve- policy, today he will offer his thoughts on break- ment Prizewinners and two exceptional Young through opportunities for mental health. Investigator Grantees, on topics ranging from schizophrenia and addiction to childhood We would like to extend special thanks to our interventions and the brain circuitry behind sponsors The Allergan Foundation and Sunov- mood disorders. ion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. for their charitable support of this year’s symposium. The Outstanding Achievement Prizewin- ners are selected by special committees of We hope today’s conference will inspire you. the Foundation’s Scientific Council, a volun- Our shared commitment to advance science teer group of 177 pre-eminent mental health will change what it means to live with a mental professionals across disciplines in brain and illness and open possibilities for more people to behavior research, who also select each year’s live full, happy, and productive lives. In our 30th Young Investigator, Independent Investiga- anniversary year, I thank you for your ongo- tor and Distinguished Investigator Grant- ing support to help us get closer to realizing ees. Since 1987, the Foundation has awarded this vision. $380 million to fund more than 5,500 grants to more than 4,500 scientists around the Sincerely, world. These awards are made specifically to fill a gap in funding innovative research that may not be supported elsewhere, but is vital for advancement in the fields of neuroscience and psychiatry. -

Long-Lasting Potentiation of Gabaergic Synapses in Dopamine Neurons After a Single in Vivo Ethanol Exposure

The Journal of Neuroscience, March 15, 2002, 22(6):2074–2082 Long-Lasting Potentiation of GABAergic Synapses in Dopamine Neurons after a Single In Vivo Ethanol Exposure Miriam Melis, Rosana Camarini, Mark A. Ungless, and Antonello Bonci Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, California 94110 The mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system originating in the ventral (diethoxymethyl) phosphinic acid shifted PPD to PPF, indicating tegmental area (VTA) is involved in many drug-related behav- that presynaptic GABAB receptor activation, likely attributable iors, including ethanol self-administration. In particular, VTA to GABA spillover, might play a role in mediating PPD in the activity regulating ethanol consummatory behavior appears to ethanol-treated mice. The activation of adenylyl cyclase by be modulated through GABAA receptors. Previous exposure to forskolin increased the amplitude of GABAA IPSCs and the ethanol enhances ethanol self-administration, but the mecha- frequency of mIPSCs in the saline- but not in the ethanol- nisms underlying this phenomenon are not well understood. In treated animals. Conversely, the protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor this study, we examined changes occurring at GABA synapses N-[z-( p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfona- onto VTA DA neurons after a single in vivo exposure to ethanol. mide significantly decreased both the frequency of spontane- We observed that evoked GABAA IPSCs in DA neurons of ous mIPSCs and the amplitude of GABAA IPSCs in the ethanol- ethanol-treated animals exhibited paired-pulse depression treated mice but not in the saline controls. The present results (PPD) compared with saline-treated animals, which exhibited indicate that potentiation of GABAergic synapses, via a PKA- paired-pulse facilitation (PPF). -

Report Drugs of Abuse and Stress Trigger a Common Synaptic Adaptation in Dopamine Neurons

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Neuron, Vol. 37, 577–582, February 20, 2003, Copyright 2003 by Cell Press Drugs of Abuse and Stress Trigger Report a Common Synaptic Adaptation in Dopamine Neurons Daniel Saal,1,3 Yan Dong,1,3 Antonello Bonci,2 is the subject of debate (Berridge and Robinson, 1998), and Robert C. Malenka1,* there is no doubt that the discovery of this common 1Nancy Pritzker Laboratory action of addictive drugs, despite their very different Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences molecular actions, has had a major influence on thinking Stanford University School of Medicine about both the neurobiological basis of addiction as Palo Alto, California 94304 well as the brain mechanisms mediating reinforcement 2 Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center and reward-based learning (Waelti et al., 2001). Department of Neurology and Recently we found that a single in vivo exposure to Wheeler Center for the Neurobiology of Addiction cocaine caused an enhancement of synaptic strength University of California, San Francisco at excitatory synapses on midbrain DA neurons (Ungless San Francisco, California 94110 et al., 2001) and that this shared several features with long-term potentiation (LTP), the leading model for the cellular changes that mediate learning and memory Summary (Martin et al., 2000). Here we examine whether in vivo administration of other commonly abused drugs causes Drug seeking and drug self-administration in both ani- a similar synaptic change. Furthermore, because in both mals and humans can be triggered by drugs of abuse humans and animals stress facilitates the initial acquisi- themselves or by stressful events. -

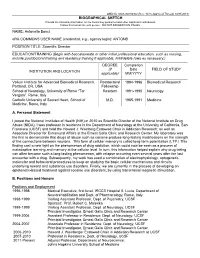

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH NAME: Antonello Bonci Era COMMONS

OMB No. 0925-0001/0002 (Rev. 10/15 Approved Through 10/31/2018) BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Provide the following information for the Senior/key personnel and other significant contributors. Follow this format for each person. DO NOT EXCEED FIVE PAGES. NAME: Antonello Bonci eRA COMMONS USER NAME (credential, e.g., agency login): ANTONB POSITION TITLE: Scientific Director EDUCATION/TRAINING (Begin with baccalaureate or other initial professional education, such as nursing, include postdoctoral training and residency training if applicable. Add/delete rows as necessary.) DEGREE Completion (if Date FIELD OF STUDY INSTITUTION AND LOCATION applicable) MM/YYYY Vollum Institute for Advanced Biomedical Research, Postdoctoral 1994-1996 Biomedical Research Portland, OR, USA Fellowship School of Neurology, University of Rome “Tor Resident 1991-1995 Neurology Vergata”, Rome, Italy Catholic University of Sacred Heart, School of M.D. 1985-1991 Medicine Medicine, Rome, Italy A. Personal Statement I joined the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2010 as Scientific Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). I was professor in residence in the Department of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and held the Howard J. Weinberg Endowed Chair in Addiction Research; as well as Associate Director for Extramural Affairs at the Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center. My laboratory was the first to demonstrate that drugs of abuse such as cocaine produce long-lasting modifications on the strength of the connections between neurons. This form of cellular memory is called long-term potentiation (LTP.) This finding cast a new light on the phenomenon of drug addiction, which could now be seen as a process of maladaptive learning and memory at the cellular level. -

Globus Pallidus Dynamics Reveal Covert Strategies for Behavioral Inhibition

This is a repository copy of Globus pallidus dynamics reveal covert strategies for behavioral inhibition. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/161807/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Gu, B.-M., Schmidt, R. orcid.org/0000-0002-2474-3744 and Berke, J.D. (2020) Globus pallidus dynamics reveal covert strategies for behavioral inhibition. eLife. e57215. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57215 © 2020 The Authors. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) permitting unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ ! 1 Globus pallidus dynamics reveal covert strategies for behavioral inhibition. 2 Bon-Mi Gu1, Robert Schmidt2, and Joshua D. Berke1,3* 3 1) Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, USA. 4 2) Department of Psychology, University of Sheffield, UK. 5 3) Department of Psychiatry; Neuroscience Graduate Program; Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience; 6 Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, USA. -

A Subpopulation of Neurochemically-Identified Ventral Tegmental Area Dopamine Neurons Is Excited by Intravenous Cocaine

The Journal of Neuroscience, February 4, 2015 • 35(5):1965–1978 • 1965 Systems/Circuits A Subpopulation of Neurochemically-Identified Ventral Tegmental Area Dopamine Neurons Is Excited by Intravenous Cocaine X Carlos A. Mejias-Aponte,1 Changquan Ye,1 Antonello Bonci,2,4 Eugene A. Kiyatkin,3 and Marisela Morales1 1Integrative Neuroscience Research Branch, Neuronal Networks Section, 2Cellular Neurobiology Research Branch, Synaptic Physiology Section, and 3Behavioral Neuroscience Research Branch, Behavioral Neuroscience Section, In Vivo Electrophysiology Unit, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Drug Abuse, Baltimore, Maryland 21224, and 4Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21205 Systemic administration of cocaine is thought to decrease the firing rates of ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopamine (DA) neurons. However, this view is based on categorizations of recorded neurons as DA neurons using preselected electrophysiological characteristics lacking neurochemical confirmation. Without applying cellular preselection, we recorded the impulse activity of VTA neurons in re- sponse to cocaine administration in anesthetized adult rats. The phenotype of recorded neurons was determined by their juxtacellular labeling and immunohistochemical detection of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a DA marker. We found that intravenous cocaine altered firing rates in the majority of recorded VTA neurons. Within the cocaine-responsive neurons, half of the population was excited and the other half was inhibited. Both populations had similar discharge rates and firing regularities, and most neurons did not exhibit changes inburstfiring.InhibitedneuronsweremoreabundantintheposteriorVTA,whereasexcitedneuronsweredistributedevenlythroughout the VTA. Cocaine-excited neurons were more likely to be excited by footshock. Within the subpopulation of TH-positive neurons, 36% were excited by cocaine and 64% were inhibited. -

Neuroplastic Alterations in the Limbic System Following Cocaine Or Alcohol Exposure

Neuroplastic Alterations in the Limbic System Following Cocaine or Alcohol Exposure Garret D. Stuber, F. Woodward Hopf, Kay M. Tye, Billy T. Chen, and Antonello Bonci Contents 1 Introduction . 4 2 Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors . 5 3 Cocaine-Induced Synaptic Plasticity in Midbrain DA Neurons . 6 4 Cocaine-Induced Synaptic Plasticity in the NAc . 8 5 Amygdala Plasticity and Drugs of Abuse . 9 6 Alcohol and Plasticity in Glutamate Receptors . 12 7 Altered Intrinsic Excitability After Alcohol or Cocaine . 14 8 Conclusions and Future Directions . 17 References . 18 Abstract Neuroplastic changes in the CNS are thought to be a fundamental component of learning and memory. While pioneering studies in the hippocampus and cerebellum have detailed many of the basic mechanisms that can lead to alterations in synaptic transmission based on previous activity, only more recently has synaptic plasticity been monitored after behavioral manipulation or drug exposure. In this chapter, we review evidence that drugs of abuse are powerful modulators of synaptic plasticity. Both the dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area as well medium spiny neurons in nucleus accumbens show enhanced excitatory synaptic strength following passive or active exposure to drugs such as cocaine and alcohol. In the VTA, both the enhancement of excitatory synaptic strength and the acquisition of drug-related behaviors depend on signaling through the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) which are mechanistically thought to lead to increased synaptic insertion of a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4- isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs). Synaptic insertion of AMPARs by drugs of abuse can be long lasting, depending on the route of administration, G.D. -

Prelimbic Cortex Is a Common Brain Area Activated During Cue‐Induced Reinstatement of Cocaine and Heroin Seeking in A

Received: 21 June 2018 | Revised: 18 September 2018 | Accepted: 20 September 2018 DOI: 10.1111/ejn.14203 RESEARCH REPORT Prelimbic cortex is a common brain area activated during cue- induced reinstatement of cocaine and heroin seeking in a polydrug self- administration rat model Francisco J. Rubio1 | Richard Quintana-Feliciano1 | Brandon L. Warren1 | Xuan Li2 | Kailyn F. R. Witonsky2 | Frank Soto del Valle1 | Pooja V. Selvam1 | Daniele Caprioli2,3 | Marco Venniro2 | Jennifer M. Bossert2 | Yavin Shaham2 | Bruce T. Hope1 1Neuronal Ensembles in Addiction Section, Behavioral Neuroscience Research Abstract Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse Many preclinical studies examined cue-induced relapse to heroin and cocaine seek- Intramural Research Program, National ing in animal models, but most of these studies examined only one drug at a time. In Institutes of Health, Baltimore, Maryland human addicts, however, polydrug use of cocaine and heroin is common. We used a 2Neurobiology of Relapse Section, Behavioral Neuroscience Research Branch, National polydrug self- administration relapse model in rats to determine similarities and dif- Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research ferences in brain areas activated during cue- induced reinstatement of heroin and co- Program, National Institutes of Health, caine seeking. We trained rats to lever press for cocaine (1.0 mg/kg per infusion, Baltimore, Maryland 3 3- hr/day, 18 day) or heroin (0.03 mg/kg per infusion) on alternating days (9 day for Santa Lucia Foundation (IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia), Rome, Italy each drug); drug infusions were paired with either intermittent or continuous light cue. Next, the rats underwent extinction training followed by tests for cue- induced Correspondence Bruce T. -

How Preclinical Models Evolved to Resemble the Diagnostic Criteria of Drug Addictionpreclinical Models Clinical Relevance to Ad

Author's Accepted Manuscript How preclinical models evolved to resemble the diagnostic criteria of drug addiction Aude Belin-Rauscent, Maxime Fouyssac, Antonello Bonci, David Belin www.sobp.org/journal PII: S0006-3223(15)00047-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.01.004 Reference: BPS12434 To appear in: Biological Psychiatry Cite this article as: Aude Belin-Rauscent, Maxime Fouyssac, Antonello Bonci, David Belin, How preclinical models evolved to resemble the diagnostic criteria of drug addiction, Biological Psychiatry, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. biopsych.2015.01.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. How preclinical models evolved to resemble the diagnostic criteria of drug addiction Aude Belin-Rauscent1,2, Maxime Fouyssac1,2, Antonello Bonci3, David Belin1,2 1 Department of Pharmacology, University of Cambridge, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 1PD, UK 2 Behavioral and Clinical Neuroscience Institute of the University of Cambridge. 3 Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Baltimore, Maryland 21014 To whom correspondence should be addressed: Antonello Bonci [email protected] Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. -

Sunday, March 29

Motivational Circuits in Natural and Learned Behaviors Sunday, March 29 3:00 pm Check-in 6:00 pm Reception (Lobby) 7:00 pm Dinner 8:00 pm Welcome and Opening Remarks 8:05 pm Session 1 Chair: Scott Sternson 8:05 pm Wolfram Schultz, University of Cambridge The dopamine reward signal codes economic utility 8:30 pm Nora Volkow, National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH DA role in sustaining effort by engaging prefrontal circuits and disengaging default mode network and how these systems get disrupted in addiction 8:55 pm Refreshments available at Bob’s Pub NOTE: Meals are in the Dining Room Talks are in the Seminar Room Posters are in the Lobby 3/27/15 Motivational Circuits in Natural and Learned Behaviors Monday, March 30 7:30 am Breakfast (service ends at 8:45am) 9:00 am Session 2 Chair: Ron Stoop 9:00 am Naoshige Uchida, Harvard University Arithmetic of dopamine reward prediction errors 9:25 am Patricia Janak, Johns Hopkins University Parsing the role of dopamine neurons in learning and performance 9:50 am Joshua Dudman, Janelia Research Campus/HHMI The vigorous pursuit of reward 10:15 am Break 10:45 am Session 3 Chair: Gul Dolen 10:45 am Howard Fields, University of California, San Francisco Mesocorticolimbic mediation of learned appetitive behaviors: A circuit analysis 11:10 am Kent Berridge, University of Michigan Affective neuroscience of reward and motivation: Liking, wanting, dread and disgust 11:35 pm Jeffrey Friedman, Rockefeller University Radiowave control of feeding and glucose metabolism 12:00 pm Bernardo Sabatini, HHMI/Harvard -

NIDA Researchers Suggest New Direction for Treating Addictions

Share 2 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In The Voice of the American Psychiatric Association and the Psychiatric Community TUESDAY, APRIL 23, 2013 NIDA Researchers Suggest New Direction for RSS FEED Treating Addictions Subscribe in a reader Using optogenetics, essentially shining a light, on SUBSCRIBE VIA EMAIL particular cells in the prefrontal cortex can reduce Enter your Email cocaine addiction in rats, according to a study published April 3 in Nature. The senior scientist was Antonello Bonci, M.D., scientific director of the NEWS FROM CURRENT ISSUE Subscribe! National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). "Our - Effects of Bullying Don’t End results can be immediately translated to clinical When School Does research settings with humans, and we are WEEKLY NEWSLETTER - Schizotypal Personality planning clinical trials to stimulate this brain Disorder Linked to Brain region using noninvasive methods," Bonci reported Changes in a press statement. "By targeting a specific portion of the prefrontal cortex, our hope is to - NYSPA Is Lead Plaintiff in reduce compulsive cocaine-seeking and craving in patients." Suit Against UnitedHealth "This exciting study offers a new direction in research for the treatment of cocaine and possibly other addictions," added NIDA Director Nora Volkow, BLOG ARCHIVE M.D. "We already knew, mainly from human brain imaging studies, that ▼ 2013 (153) deficits in the prefrontal cortex are involved in drug addiction. Now that ▼ April (38) we have learned how fundamental these deficits are, we feel more Patients Get Opportunity confident than ever about the therapeutic promise of targeting that part to Safely Dispose of of the brain." Unwa.. -

Amygdala Processing of the Formation and Retrieval of Cue-Reward Associations

Amygdala processing of the formation and retrieval of cue-reward associations Copyright 2008 by Kay M. Tye ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is dedicated to my parents for their unconditional love and their undoubting faith in me. Both of them came to this country with nothing except their hope for a better life, and both of them have built successful careers in science that they are passionately in love with while raising two rambunctious daughters. I want to thank my father, S. Henry Tye, the most humble genius that I have ever met, for teaching me how to enjoy life. My father is a truly great man who walks softly but changes our view of the universe and is a constant inspiration for me to be a better person. I want to thank my mother, Bik K. Tye, who has never let anyone tell her that something couldn’t be done, and has taught me to do the same. My mother is the picture of intelligence, resilience and courage – she always says exactly what she thinks, and knows when I need comfort and when I need to stop whining and start working harder. Words cannot express how grateful I am to them for all that they have made possible for me, and I hope to make them proud. I also want to thank my sister, Lynne D. Tye, who is and always will be a part of me. This thesis reflects the patience, wisdom and mentoring ability of my advisor and mentor, Patricia H. Janak. I am forever indebted to Tricia for taking me in when I was a discouraged and lost rotation student on the verge of dropping out of graduate school, and reviving my belief in myself as well as my love for science.