View PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Native Land Acknowledgement

2021 Massachusetts & Rhode Island Land Conservation Conference Land Acknowledgement It is important that we as a land conservation community acknowledge and reflect on the fact that we endeavor to conserve and steward lands that were forcibly taken from Native people. Indigenous tribes, nations, and communities were responsible stewards of the area we now call Massachusetts and Rhode Island for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, and Native people continue to live here and engage in land and water stewardship as they have for generations. Many non-Native people are unaware of the indigenous peoples whose traditional lands we occupy due to centuries of systematic erasure. I am participating today from the lands of the Pawtucket and Massachusett people. On the screen I’m sharing a map and alphabetical list – courtesy of Native Land Digital – of the homelands of the tribes with territories overlapping Massachusetts and Rhode Island. We encourage you to visit their website to access this searchable map to learn more about the Indigenous peoples whose land you are on. Especially in a movement that is committed to protection, stewardship and restoration of natural resources, it is critical that our actions don’t stop with mere acknowledgement. White conservationists like myself are really only just beginning to come to terms with the dispossession and exclusion from land that Black, Indigenous, and other people of color have faced for centuries. Our desire to learn more and reflect on how we can do better is the reason we chose our conference theme this year: Building a Stronger Land Movement through Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. -

James Brown, 1698-1739, Great-Grandson of Chad Brown

REYNOLDS HISTORICAL GENEALOGY COLLECTION Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 https://archive.org/details/jamesbrown16981700wood BROWN 1698-1739 Great-Grandson of Chad Brown By o JOHN CARTER BROWN WOODS Great-great'great'grandson of James Brown 013 Reprinted from 940i 1 * THE LETTER BOOK OF JAMES BROWN Providence, R. I., 1929 . • / ■ ;• . •• :£• -■ ' . ,v.,-. £ ir ■ ; • . -• • i * ' s . .. % - > . ' •. - . c tjj. • a* - • ! ' , - ' • ■ -V f- - *• v *- v . - - Ih f * ■ •• • ■. <• . - ' 4 * i : Or. f JAMES BROWN ; i (j.... 1698-1739 ; •hi.. • • Qreat-greai>great'grandson of James Brown r.Tb • * . James Brown,1 Jr., great grandson of Chad Brown, and second son of the Rev. James and Mary (Harris) Brown, was born in Providence, March 22, 1698, and died there April 27, 1739. He married, December 21, 1722, Hope Power (b. Jan. 4, 1702—d. June 8, 1792), daughter of Nicholas and Mercy (Tillinghast) Power, and grand-daughter of the Rev. Pardon Tillinghast. With his younger brother, Obadiah, he established the Com¬ mercial House of the Browns, of Providence, lv. 1., that later became Nicholas Brown & Co., Brown & Benson,-and finally Brown & Ives. There were five sons and one daughter. The eldest son, James, died in York, Va., in 1750, while master of a vessel. The other four, Nicholas, Joseph, John and Moses, later familiarly known as the “Four Brothers/' acquired great distinction in private and public affairs, and were partners in the enterprises established by their father and uncle, that they largely extended and increased. The daughter, Mary, married Dr. John Vander- light, of Steenwyk, Holland, chemist, and a graduate of Ley¬ den University, who later became associated with his brothers- in-law in the manufacture of candles, having brought with him a knowledge of the Dutch process of separating spermaceti from its oil. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

The Narragansett Planters 49

1933.] The Narragansett Planters 49 THE NARRAGANSETT PLANTERS BY WILLIAM DAVIS MILLER HE history and the tradition of the "Narra- T gansett Planters," that unusual group of stock and dairy farmers of southern Rhode Island, lie scattered throughout the documents and records of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and in the subse- quent state and county histories and in family genealo- gies, the brevity and inadequacy of the first being supplemented by the glowing details of the latter, in which imaginative effort and the exaggerative pride of family, it is to be feared, often guided the hand of the chronicler. Edward Channing may be considered as the only historian to have made a separate study of this community, and it is unfortunate that his monograph. The Narragansett Planters,^ A Study in Causes, can be accepted as but an introduction to the subject. It is interesting to note that Channing, believing as had so many others, that the unusual social and economic life of the Planters had been lived more in the minds of their descendants than in reality, intended by his monograph to expose the supposed myth and to demolish the fact that they had "existed in any real sense. "^ Although he came to scoff, he remained to acknowledge their existence, and to concede, albeit with certain reservations, that the * * Narragansett Society was unlike that of the rest of New England." 'Piiblinhed as Number Three of the Fourth Scries in the John» Hopkini Umtertitj/ Studies 111 Hittirieal and Political Science, Baltimore, 1886. "' l-Mward Channing^—came to me annoiincinn that he intended to demolish the fiction thiit they I'xistecl in any real Bense or that the Btnte uf society in soiithpni Rhode Inland iliiTcrpd much from that in other parts of New EnRland. -

United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. Scholarship Application Checklist

United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. Scholarship Application Checklist Completed application Three (3) letters of recommendation Verification of tribal enrollment in a USET Tribe (copy of ID card or verification letter from Tribal Clerk) Incoming Freshman or First Year Grad Student A copy of your high school or college transcript Letter of acceptance from college Transfer Students Letter of acceptance from college Transcripts from any other colleges attended Continuing Students Most recent college transcript Personal Statement Undergrad – 250 word minimum (State any future goals, obstacles overcome, challenges, etc.) Grad – 500 word minimum (State any future goals, reasons for attending graduate school, obstacles overcome, challenges, etc.) United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. Scholarship Application Please type or print. All fields must be complete. (Incomplete applications will not be considered.) I. Personal Information First name Last M.I. Mailing address City State ZIP Phone number Date of birth SSN USET Member Tribe Tribal Enrollment # II. Academic Information High School Graduation attended or GED date Other Post- secondary Dates institution attended attended School year New Student applying for Continuing Student Term applying for Fall Spring Summer Winter College/University you will attend College/University address Undergrad: Full-time (12 credits or more) Part-time (11 credits or fewer) Status Grad: Full-time (9 credits or more) Part-time (8 credits or fewer) Year level Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Graduate College major Expected graduation date Expected degree AA AS AAS BA MA MS PhD JD Number of college credit hours to date Current GPA Cumulative GPA United South and Eastern Tribes, Inc. Scholarship Application III. -

The General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts State House, Boston, MA 02133-1053

The General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts State House, Boston, MA 02133-1053 April 7, 2020 David L. Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington DC 20240 Dear Secretary Bernhardt, We are deeply dismayed and disappointed with the Department of the Interior's recent decision to disestablish and take lands out of trust for the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe on March 27, 2020. Not since the mid-twentieth century has an Interior Secretary taken action to disestablish a reservation. This outrageous decision comes as we mark 400 years since the arrival of the Pilgrims in 1620 and recognize the People of the First Light who inhabited these shores for centuries before contact. The Department’s capricious action brings shame to your office and to our nation. Your decision was cruel and it was unnecessary. You were under no court order to take the Wampanoag land out of trust. Further, litigation to uphold the Mashpee Wampanoag’s status as a tribe eligible for the benefits of the Indian Reorganization Act is ongoing. Your intervention was without merit and completely unnecessary. The fact that the Department made this announcement on a Friday afternoon in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates a callous disregard for human decency. Mashpee Wampanoag leaders were focused on protecting members of their tribe, mobilizing health care resources, and executing response plans when they received your ill-timed announcement. As you are well aware, the Department of the Interior holds a federal trust responsibility to tribes, which includes the protection of Native American lands. -

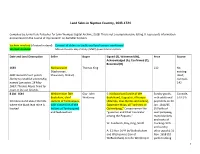

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

Ancestry of Alice Maud Clark – an Ahnentafel Book

Ancestry of Alice Maud Clark – An Ahnentafel Book - Including Clark, Derby, Fiske, Bixby, Gilson, Glover, Stratton and other families of Massachusetts by A. H. Gilbertson 8 January 2021 version 0.154 © copyright A. H. Gilbertson, 2012-2021 © copyright 2016-2021 A. H. Gilbertson Table of Contents Preface............................................................................................................................................. 5 Alice Maud Clark (1) ...................................................................................................................... 6 John Richardson Clark (2) and Caroline Maria Derby (3) ............................................................. 9 Horatio Clark (4) and Betsey Bixby (5) ........................................................................................ 13 John Derby (6) and Martha Fiske (7) ............................................................................................ 16 Moses Clark (8) and Martha Rogers (9) ....................................................................................... 18 Asa Bixby (10) and Lucy Gilson (11)........................................................................................... 20 John Derby (12) and Mary Glover (13) ........................................................................................ 22 Robert Fiske (14) and Nancy Stratton (15) ................................................................................... 23 Norman Clark (16) and Hannah Bird (17) ................................................................................... -

My Story, and Some Things I Believe and Teach N

MY STORY, AND SOME THINGS I BELIEVE AND TEACH N. Sebastian Desent, Ph.D., Th.D., D.D.; Pastor, Historic Baptist Church www.HistoricBaptist.org Personal Background. I was saved in February, 1985 by reading a King James paperback New Testament that I found in a garbage can. Having some time on my hands, I started reading this book, wondering why it was discarded. At the time, I did not realize it was a New Testament. My attention was drawn especially to the Epistle to the Romans because of what I knew about history. I thought this was teaching on the Roman Empire, but after a short amount of reading I soon realized this was a very special book. By chapter ten, I was kneeling and asking forgiveness of my God and Savior. I was twenty-five years old. I had lived a life mainly as a loner. I had traveled, went to various schools, being pretty much on my own since fifteen years of age. I had joined the Marine Corps a week after turning seventeen and lived that lifestyle for a few years. Shortly after Jesus saved me I was moved by the Holy Ghost to stop swearing, speaking filthy things (jokes and the like), and to stop the consumption of women, tobacco, alcohol and drugs. Most people who knew me saw the dramatic change, but not many responded to my testimony of salvation and the power of the gospel. I did witness to many who knew the old me, but my relationship with these people did not last very long. -

Identity As Idiom: Mashpee Reconsidered

. Identity as Idiom: Mashpee Reconsidered Jo Carrillo* Introduction In the late 1970s, at the height of the American Indian rights movement, the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe filed a lawsuit in federal court asking for return of ancestral land.' Before the Mashpee land claim could be adjudicated, however, the tribe had to prove that it was (just as its ancestral predecessor had been) the sort of American Indian tribe with which the United States could establish and maintain a govemment-to-govemment relationship. The Mashpee litigation was remarkable. For one thing, it raised profound and lingering questions about identity, assimilation, and American Indian nationhood. For another, it illustrated, in ways that become starker and starker as time goes on, the injustice that the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe has endured. The Mashpee had survived disease, forced conversion, forced education; they had maneuvered through passages of history in which well-meaning and not-so-well-meaning non-Indians "freed" them from their Indian status, thereby exposing Mashpee land to market forces; they had survived the loss of their language. In spite of it all, the Mashpee maintained their cultural identity, only later to be pronounced "assimilated," and therefore ineligible for federal protection as an American Indian tribe. What the Mashpee tried to characterize as syncretic adaptations to the harsh realities of colonialism, others called the inevitable and wholehearted embrace by the Indians of "superior, rational, ordered" white ways. Hence when the Mashpee prayed with their own Indian Baptist ministers, non- Indian commentators claimed they had embraced an African-American version of Protestantism; when they spoke English, they were said to have benefitted fi-om white education; when they used legal forms like deeds, it was cited as evidence of their preference for American law. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indica+ion that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs” if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.