Samuel Lines and Sons: Rediscovering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesse Bruton 6 July – 11 September 2016

Ikon Gallery, 1 Oozells Square, Brindleyplace, Birmingham B1 2HS 0121 248 0708 / www.ikon-gallery.org Open Tuesday-Sunday, 11am-5pm / free entry Jesse Bruton 6 July – 11 September 2016 Jesse Bruton, Devil's Bowl (c.1965). Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist. Jesse Bruton is one of the founding artists of Ikon. This exhibition (6 July – 11 September 2016) tells the fascinating story of his artistic development, starting in the 1950s and ending in 1972 when Bruton abandoned painting for painting conservation. Having studied at the College of Art in Birmingham, Bruton was a lecturer there during the early 1960s, following a scholarship year in Spain and a stint of National Service. He went on to teach at the Bath Academy of Art, Corsham, 1966-69. He exhibited in a number of group shows in Birmingham, especially at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, and had a solo exhibition at Ikon shortly after the gallery opened to the public in 1965, and again in 1967. Like many of his contemporaries, Bruton developed an artistic proposition inspired by landscape. Many of his early paintings were of the Welsh mountains and the Pembrokeshire coast. Alive to the aesthetic possibilities of places he visited, he made vivid painterly translations based on a stringent palette of black and white. They reflected his particular interest “in the way things worked, things like valleys, rock formations and rivers ...” “I wasn’t particularly interested in colour. I wanted to limit the formal language I was using – to work tonally gradating from black to white, leaching out the medium from the paint in order to enhance a variety of textures. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Elkington & Co. and the Art of Electro-Metallurgy, circa 1840-1900. Alistair Grant. A Thesis Submitted to the University of Sussex for Examination for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September 2014. 2 I hereby declare that this thesis is solely my own work, and has not been, and will not be submitted in whole, or in part, to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 This PhD thesis is dedicated to my wife Lucy and my daughter Agnes. I would like to thank my wife, Dr. Lucy Grant, without whose love, encouragement, and financial support my doctoral studies could not have happened. Her fortitude, especially during the difficult early months of 2013 when our daughter Agnes was ill, anchored our family and home, and enabled me to continue my research and complete this PhD thesis. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Maurice Howard. Having nurtured my enthusiasm for Art History as an undergraduate at the University of Sussex from 1983-1986, when I approached him, 23 years later, about pursuing PhD research into Elkington & Co. -

Edgbaston Central Campus Development Hybrid Planning Application March 2012

Edgbaston Central Campus Development Hybrid Planning Application March 2012 Strategic Heritage Assessment Edgbaston Central Campus Development - Hybrid Planning Application Strategic Heritage Assessment Prepared for the University of Birmingham March 2012 Contents 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 2.0 Historical Development ............................................................................................4 2.1 Archaeology ......................................................................................................................4 2.2 The Manor of Edgbaston..............................................................................................4 2.3 The Calthorpe Estate ......................................................................................................8 2.4 The University of Birmingham ................................................................................ 15 2.5 The Vale ............................................................................................................................ 32 3.0 Significance ................................................................................................................34 3.1 Assessing Significance ............................................................................................... 34 3.2 Designated heritage assets ...................................................................................... 37 3.3 Undesignated heritage -

APPENDIX 2 Full Business Case (FBC) 1. General Information

APPENDIX 2 Full Business Case (FBC) 1. General Information Directorate Economy Portfolio/Committee Leader’s Portfolio Project Title Jewellery Project Code Revenue TA- Quarter 01843-01 Cemeteries Capital – to follow Project Description Aims and Objectives The project aims to reinstate, restore and improve the damaged and vulnerable fabric of Birmingham’s historic Jewellery Quarter cemeteries – Key Hill and Warstone Lane – and make that heritage more accessible to a wider range of people. Their importance is recognised in the Grade II* status of Key Hill Cemetery in the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest, and the Grade II status of Warstone Lane Cemetery. The project is an integral part of the wider heritage of the Jewellery Quarter and complements the other heritage investment taking place here, such as the JQ Townscape Heritage programme and the completion of the Coffin Works (both part-funded by HLF). Heritage is a key part of the Jewellery Quarter with over 200 listed buildings and four other museums (Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Pen Room, Coffin Works, JW Evans). The funding provides an opportunity to bring much needed investment to conserve and enhance two important listed cemeteries, providing a resource and opportunities for visitors and residents alike to visit, enjoy and get involved with. The project will deliver the following (full details are set out in the Design Specification): Full 10-year management and maintenance plans for both cemeteries Interpretation plan Capital works - Warstone Lane cemetery Reinstatement of the historical boundary railings (removed in the 1950s), stone piers and entrance gates on all road frontages; Resurfacing pathways to improve access; Renovation of the catacomb stonework and installation of a safety balustrade; Creation of a new Garden of Memory and Reflection in the form of a paved seating area reinterpreting the footprint of the former (now demolished) chapel; General tree and vegetation management. -

David Prentice 1936 – 2014

DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work - a Selling Retrospective: Part II Autumn 2017 Period, Modern & Contemporary Art DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work - a Selling Retrospective: PART II includes paintings of all periods but also features examples inspired by the Scilly Isles, City of London paintings, the Isle of Skye and The House that Jack Built. Saturday, 7th October 11am - 5pm Sunday, 8th October 11am - 3pm Continues through to 4th November Monday - Saturday 10am - 5pm Sligachan Bridge, Isle of Skye (2012) Watercolour, 23 x 33 ins The Old Dairy Plant · Fosseway Business Park · Stratford Road Moreton-in-Marsh · Gloucestershire · GL56 9NQ Front cover illustration: King’s Reach West (2003) Tel: 01608 652255 · email: [email protected] Oil on canvas, 46 x 56 ins www.johndaviesgallery.com DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work: Part II From both a public perspective and a gallery point of view, range of what are widely regarded as under-appreciated part one of this two-part retrospective for David has been a works of art. distinctly rewarding and illuminating event. First and foremost, the throughput of visitors to the exhibition has been very high. Included in Part ll of A Window on a Life’s Work are five Secondly, the positive reaction of this elevated number of bodies of work – abstract works from the 1960’s and 1970’s observers to David’s work has been significant and voluble. (contrasting to those in Part I), a small group of significant and particularly dynamic paintings derived from the Scilly Isles, a I include in this ‘public’ many of David’s ex-pupils who have good number of the hugely impressive City of London displayed a strong, universal affection for their tutor of fifty canvasses; highly atmospheric works inspired by the Isle of years-ago. -

Statistical Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Acid Deposition in the West Midlands, England, United Kingdom

Statistical Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Acid Deposition in the West Midlands, England, United Kingdom A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Avery Rose Cota-Guertin IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Dr. Howard Mooers January 2012 © Avery Rose Cota-Guertin 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to take this time to thank those people who played a crucial part in the completion of this thesis. I would like to thank my mother, Roxanne, and father, Jim. Without their unconditional love and support I would not be where I am today. I would also like to thank my husband, Greg, for his continued and everlasting support. With this I owe them all greatly for being my rock through this entire process. I would like to thank my thesis committee members for their guidance and support throughout this journey. First and foremost, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Howard Mooers, for the advisement and mentoring necessary for a successful completion. Secondly, I would like to extend great thanks to Dr. Ron Regal for patiently mentoring me through the rollercoaster ride of Statistical Analysis Software (SAS). Without his assistance in learning SAS techniques and procedures I would still be drowning in a sea of coding procedures. And thank you to Dr. Erik Brown for taking the time to serve on my thesis committee for the past two years. For taking the time out of his busy schedule to meet with Howard and me during our trip to England, I owe a great thanks to Dr. -

35 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

35 bus time schedule & line map 35 Birmingham - Hawkesley via Kings Heath View In Website Mode The 35 bus line (Birmingham - Hawkesley via Kings Heath) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Digbeth: 5:06 AM - 10:48 PM (2) Hawkesley: 5:50 AM - 11:30 PM (3) King's Heath: 11:18 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 35 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 35 bus arriving. Direction: Digbeth 35 bus Time Schedule 52 stops Digbeth Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:52 AM - 10:49 PM Monday 5:06 AM - 10:48 PM Ridgemount Drive, Hawkesley Longdales Road, Birmingham Tuesday 5:06 AM - 10:48 PM Longdales Rd, Hawkesley Wednesday 5:06 AM - 10:48 PM Parlows End, Birmingham Thursday 5:06 AM - 10:48 PM Driftwood Close, Hawkesley Friday 5:06 AM - 10:48 PM Shannon Road, Birmingham Saturday 5:09 AM - 10:50 PM Bridges Walk, Hawkesley Hawkesley Square, Hawkesley Old Portway, Birmingham 35 bus Info Cornerway, Hawkesley Direction: Digbeth Stops: 52 Longdales Rd, Hawkesley Trip Duration: 48 min Selcombe Way, Birmingham Line Summary: Ridgemount Drive, Hawkesley, Longdales Rd, Hawkesley, Driftwood Close, Green Lane Walk, Hawkesley Hawkesley, Bridges Walk, Hawkesley, Hawkesley Square, Hawkesley, Cornerway, Hawkesley, Rosebay Ave, Hawkesley Longdales Rd, Hawkesley, Green Lane Walk, Hawkesley, Rosebay Ave, Hawkesley, Primrose Hill, Primrose Hill, Pool Farm Pool Farm, Siseƒeld Rd, Pool Farm, Little Hill Grove, Pool Farm, Walkers Heath Rd, Walkers Heath, Siseƒeld Rd, Pool Farm Heathside Drive, Druids Heath, Chelworth -

Samuel Lines and Sons: Rediscovering Birmingham's

SAMUEL LINES AND SONS: REDISCOVERING BIRMINGHAM’S ARTISTIC DYNASTY 1794 – 1898 THROUGH WORKS ON PAPER AT THE ROYAL BIRMINGHAM SOCIETY OF ARTISTS VOLUME II: CATALOGUE by CONNIE WAN A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. CONTENTS VOLUME II: CATALOGUE Introductory Note page 1 Catalogue Abbreviations page 8 Catalogue The Lines Family: A Catalogue of Drawings at the page 9 Royal Birmingham Society of Artists Appendix 1: List of Works exhibited by the Lines Family at the Birmingham page 99 Society of Arts, Birmingham Society of Artists and Royal Birmingham Society of Artists 1827-1886 Appendix 2: Extract from ‘Fine Arts, Letter XIX’, Worcester Herald, July 12th, 1834 page 164 Appendix 3: Transcription of Henry Harris Lines’s Exhibition Ledger Book page 166 Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum [WOSMG:2006:22:77] -

![Blue Plaque Walk[...]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4814/blue-plaque-walk-1954814.webp)

Blue Plaque Walk[...]

1 In brief How to get there Central Edgbaston Edgbaston is an elegant leafy suburb just one mile west Blue Plaque Walk of Birmingham city centre. Walking distance Public Transport 1.6 miles / 2.57km From City By bus - using Hagley Road towards Quinton or buses to Harborne. Category By train - from New Street travel to Five Ways station. Easy For more information visit: www.networkwestmidlands.com BRIEF HISTORY of How to find Edgbaston EDGBASTON Central EDGBaSTON Celboldestone in the Doomsday book ofBy 1086 is carEdgbaston is an elegant leafy suburb just one thought to refer to Edgbaston and depicts it as an mile west of Birmingham city centre. area of cultivated land of about 250 acres. Places to eat, drink and relax inEdgbaston church dates from the 13th centuryEdgbaston and Village is easily accessible by car. Car parking Edgbaston Hall, the manor house, now the Golf Public Transport club, somewhat later. During the Englishis civil available war, at pay and display car parks, and there is Edgbaston: www.edgbastonvillage.co.ukwhen Edgbaston Hall was the seat of Robert From City Middlemore, a Roman Catholic and limitedRoyalist, free Buseson-street along Hagleycar parking. Road towards Quinton, buses to Harborne Parliamentarian troops extensively damaged the church and took over the Hall, which was eventually destroyed. In 1717, the Middlemore line Train to Five Ways station Walk available through the ‘Walkhaving Run been extinguished, the lordship of BRIEF HISTORYEdgbaston was of purchased byHow Sir Richard to Gough. find Edgbaston EDGBASTON Central Cycle’ app: www.walkruncycle.com/EDGBaSTONDuring 10 years at Edgbaston he rebuiltWalk both the orWalk Cycle developed in 2018 by Heritage Celboldestone in the Doomsdayhall and thebook church. -

Programme July – September 2014 Free Entry

Programme July – September 2014 www.ikon-gallery.org Free entry As Exciting As We Can Make It Rasheed Araeen Art & Language Ikon in the 1980s Sue Arrowsmith 2 July – 31 August 2014 Kevin Atherton First and Second Floor Galleries Terry Atkinson Gillian Ayres A survey of Ikon’s programme from the 1980s, Bernard Bazile As Exciting As We Can Make It, is a highlight of our Ian Breakwell 50th anniversary year. A comprehensive exhibition, Vanley Burke 2 including work by 29 artists, it features painting, Eddie Chambers sculpture, installation, film and photography actually Shelagh Cluett The 1980s saw the rise of postmodernism, a fast-moving shown at the gallery during this pivotal decade. Agnes Denes zeitgeist that chimed in with broader cultural shifts in Britain, in particular the politics that evolved under the Max Eastley premiership of Margaret Thatcher. There was a return to figurative painting; a shameless “appropriationism” that Charles Garrad saw artists ‘pick and mix’ from art history, non-western art and popular culture; and an enthusiastic re-embrace of Ron Haselden Dada and challenge to notions of self contained works of art Susan Hiller through an increasing popularity of installation. Ikon had a reputation by the end of the 1980s as a key John Hilliard national venue for installation art. Dennis Oppenheim’s Albert Irvin extraordinary work Vibrating Forest (From the Fireworks Series) (1982), made from welded steel, a candy floss machine and Tamara Krikorian unfired fireworks, returns to Ikon for the exhibition, as does Charles Garrad’s Monsoon (1986) featuring a small building, Pieter Laurens Mol set out as a restaurant somewhere in South East Asia, subjected to theatrical effects of thunder and lightning in an Mali Morris evocative scenario. -

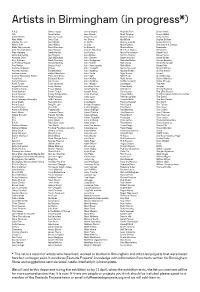

Artists in Birmingham (In Progress*)

Artists in Birmingham (in progress*) A.A.S. Darren Joyce Jenny Moore Michelle Bint Simon Davis A2rt Dave Patten Jess Hands Mick Thacker Simon Webb Adele Prince David A. Hardy Jesse Bruton Mike Holland Sofia Hulten Alan Miller David Cox Jim Byrne Mo White Sophie Bullock Alastair Scruton David Mabb Jo Griffin Mohammed Ali Space Banana Albert Toft David Miller Jo Loki Mona Casey Sparrow and Castice Aleks Wojtulewicz David Prentice Jo Roberts Monica Ross Spectacle Alex Gene Morrison David Rowan Joanne Masding Mrs G. A. Barton Steve Bell Alex Marzeta Derek Horton Joe Hallam Myria Panayiotou Steve Field Alicia Dubnyckyj Des Hughes Joe Welden Nathan Hansen Steve Payne Amanda Grist Dick McGowan John Barrett Nayan Kulkarni Steve Wilkes Amy Kirkham Dinah Prentice John Bridgeman Nicholas Bullen Steven Beasley An Endless Supply Donald Rodney John Butler Nick Jones Stuart Mugridge Ana Rutter Easton Hurd John Hammersley Nick Wells Stuart Tait Andrew Gillespie Ed Lea John Hodgett Nicola Counsell Stuart Whipps Andrew Jackson Ed Wakefield John Newling Nicolas Bullen Su Richardson Andrew Lacon Eddie Chambers John Poole Nigel Amson Surely? Andrew Moscardo Parker Eliza Jane Grose John Salt Nikki Pugh Surjit Simplay Andy Hunt Elizabeth Rowe John Walker Nola James Sylvani Merilion Andy Robinson Elly Clarke John Wallbank OHNE/projects Tadas Stalyga Andy Turner Emily Mulenga John Wigley Ole Hagen Ted Allen Angela Maloney Emily Warner Jonathan Shaw Oliver Braid Temper Angelina Davis Emma Macey Jony Easterby Ollie Smith Tereza Buskova Anna Barham Emma Talbot Joseph