Elite Level Refereeing in Men's Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Sherborne V Clevedon

THE ZEBRAS Match Sponsor Programme Sponsor SHERBORNE TOWN vs CLEVEDON TOWN #ZEBRAS 1 SATURDAY 12TH SEPTEMBER 2020 | KICK OFF 3PM | EMIRATES FA CUP PRELIMINARY ROUND 2 #ZEBRAS FROM THE DUGOUT WAYNE JEROME Good afternoon and a warm welcome to you all and everyone from Clevedon Town for today’s FA Cup Preliminary round tie. After a great start to the season with a 2-1 win against Premier Division side Street in the FA Cup, which not only attracted a gate of 292 it also gave the club some much-needed revenue after this COVID. It also resulted in a nice sum of money for winning the game. Since that victory, we have suffered two league defeats both by 2-0. A home fixture to Portishead and away trip to Radstock definitely not how we visualised the start of the season, but these things happen in football and it’s down to us as a group to put those wrongs right. We are an honest bunch and we know ourselves that we didn’t turn up against Portishead we looked tired and leggy from the midweek heroics against Street. Against Radstock the overall performance was more pleasing than the result but poor finishing and some questionable decisions from the officials cost us dearly. Today is a chance to take our minds off getting them much needed league points to get that monkey off our back and enjoy playing higher league opposition again in the FA Cup. So enjoy your day and always remember everyone wants the underdogs to cause an upset. -

Minutes Document for Council, 21/07/2016 19:15

Council, Thursday, 21 July 2016 Report of the Council Thursday, 21st July, 2016 (7.15 p.m. - 11.20 p.m.) Present: The Worshipful the Mayor, G. Bhamra, Z. Hussain (Deputy Mayor), Councillors Mohammad Ahmed, Mushtaq Ahmed, J. Athwal, S. Bain, S. Bellwood, I. Bond, D. Bromiley, P. Canal, M. Chaudhary, A. Choudhury, K. Chowdhury, H. Cleaver, R. Cole, H. Coomb, C. Cronin, C. Cummins, G. Deakins, L. Duddridge, Mrs M. Dunn, R. Emmett, K. Flint, J. Haran, R. Hatfull, N. Hayes, J. Hehir, J. Howard, Mrs L. Huggett, F. Hussain, M. Javed, T. Jeyaranjan, B. Jones, A. Kissin, B. Lambert, B. Littlewood, T. McLaren, P. Merry, B. Nijjar, Mrs S. Nolan, E. Norman, Mrs K. Packer, A. Parkash, K. Prince, K. Rai, T. Rashid, Mrs J. Ryan, A. Sachs, M. Santos, D. Sharma, T. Sharpe, M. Stark, W. Streeting, R. Turbefield, A. Weinberg, B. White and N. Zammett Public: 80+ Officers: Chief Executive, Corporate Director of Children & Young People, Corporate Director of Health & Social Care Integration, Corporate Director of Place, Corporate Director of Resources, Head of Corporate & Property Legal Services and Joint Head of Constitutional Services. Prayers were said by Dr. Mohammed Fahim. 1. Standing Order 68: Electronic Media (COU/01/210716) All present were reminded that in accordance with the Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014 that the public and press were permitted to report on the meeting using electronic media tools. However, oral commentary would not be permitted in the room during proceedings. All present were also advised that the meeting was being audio recorded and the recording would be available to download on Redbridge i. -

Uefa Europa League 2010/11 Season Match Press Kit

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE 2010/11 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT BSC Young Boys Odense BK Group H - Matchday 3 Stade de Suisse, Berne Thursday 21 October 2010 19.00CET (19.00 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................3 Team facts.........................................................................................................................4 Squad list...........................................................................................................................6 Fixtures and results...........................................................................................................8 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................10 Match officials..................................................................................................................12 Legend............................................................................................................................13 This press kit includes information relating to this UEFA Europa League match. For more detailed factual information, and in-depth competition statistics, please refer to the matchweek press kit, which can be downloaded at: http://www.uefa.com/uefa/mediaservices/presskits/index.html BSC Young Boys - Odense BK Thursday 21 October 2010 - 19.00CET -

2014FWC TSG Report 15082014

Technical Report and Statistics 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil™ TECHNICAL REPORT AND STATISTICS 12 June – 13 July 2014 Rapport technique et statistiques Informe técnico y estadísticas Technischer Bericht und Statistik 2 Contents 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 4 Story of the tournament 8 Technical and tactical analysis 42 Trends 60 What made the difference? 74 Confederation analysis 80 Refereeing report 106 Medical report 120 Goal-line technology 130 Statistics and team data 148 - Results and ranking 150 - Venues and stadiums 152 - Match telegrams 154 -Of fi cial FIFA awards 168 - Statistics 171 - Preliminary competition 194 - Referees and assistant referees 208 - Team data 210 - FIFA delegation 274 - FIFA Technical Study Group/Editorial 280 4 Foreword Eugenio Figueredo Chairman of the Organising Committee for the FIFA World Cup™ Dear friends of football, Attacking football, breathtaking goals and vibrant This Technical Report, produced by the experts of the crowds were at the heart of the 2014 FIFA World Cup FIFA Technical Study Group (TSG), not only represents a Brazil™. key insight into the main tactical and technical trends that marked the tournament but also an educational The “spiritual home of football” welcomed visitors tool for all 209 member associations. Indeed, we will from all over the world for an unforgettable fi esta engage all confederations in a series of conferences in that will live long in the memory of football fans order to share with them the knowledge and fi ndings everywhere. From the opening match played at the accumulated by the FIFA TSG during the 2014 FIFA Arena de São Paulo on 12 June to the epic fi nal at the World Cup. -

FLAG & WHISTLE the Darren Clark Experience

FLAG & WHI STL E Official Newletter of the BC Soccer Referees Association – Holiday Issue The Darren Clark Experience Major Leage Ref – “Kamloops This Week” newspaper by Marty Hastings This article has been edited for Flag & Whistle David Beckham is one of the best 90,500 fans at the Rose Bowl in soccer players in the world. To Darren Pasadena, Calif. A year later, he Clark, a 37-year-old assistant referee from worked a game between Costa Rica, Kamloops, the English footballing super- the home side, and Spain. star was just No. 23 in white at the MLS “There was basically the entire Cup on Saturday, December 1, 2012. Spain team on the field that had won “If somebody asks you, ‘How was that the World Cup in 2010,” said Clark, a game from a fan's perspective?’ and you teacher at Logan Lake secondary. can answer that question, you probably Clark, who started working MLS haven't been concentrating,” said Clark, games in 2008, did 13 matches last who patrolled the sidelines when the Los season, including two playoff games Angeles Galaxy downed the Houston and seven tilts featuring the Van Dynamo 3-1 at the Home Depot Centre in couver Whitecaps. An assistant ref- Carson, Calf. eree of his calibre in MLS is paid The entire on-field officiating group at $720 per game. Travel and accommo- the championship final was Canadian – a dation costs are also taken care of and Major League Soccer first. Daniel Belleau a per diem is provided. of Quebec was the game’s other assistant Clark’s Logan Lake students are referee, while Silviu Petrescu of Ontario aware of his activities away from was the match referee. -

Conference 2015 Special

R.A. BOARD VOICEOVER “Conference 2015 Special” Referees’ Association Announcement At meeting of the RA Board on Sunday 5th July 2015 the following were elected: Chairman: Paul Field Vice Chairman: Ian Campbell Treasurer: Eddie McGrath Further announcements will follow during the coming weeks as we continue to structure the RA Board. ************************************************************************************************************************************** THE THOUGHTS OF CHAIRMAN PAUL (Paul Field) I have been a member of the R.A. Board for 5 years during which time I have seen seven different Chairman, a Board of Inquiry regarding the general management of the RA, and we had an office facility which was not fit-for-purpose, The RA has now started to move forward and this is now history but let’s remember one quote which typifies the organisation: Henry Ford said – “If you always do what you’ve always done, you will always get what you’ve always got”. In the case of The R.A., a poor product which is not relevant to majority of the Refereeing family, declining membership and often people being in office for far too long. In my view, The R.A. now has to move forward and there are sound building blocks for the future which are positive steps. We need to remember that our main reason for existence is to provide a platform for on-going training, development, mentoring and mutual support. The thriving LRAs are the ones that concentrate on this, have lively debates, a good social side and little business transacted at meetings. As a collective (individually and LRA’s) we are all responsible! There is an urgent need to change people’s perception of the RA and the quality of the membership experience. -

Events in Monaco AC Milan Win the UEFA Super Cup Disciplinary

0.03 1 including Events in Monaco 03 AC Milan win the UEFA Super Cup 07 Disciplinary matters 10 News from Brussels 13 no 18 – october 2003 – october no 18 COVER IN THIS ISSUE Gala evening in Monaco 08 UEFA President Lennart Johansson hands Disciplinary cases on the rise 10 the UEFA Super Cup to AC Milan captain UEFA Champions League calendar 05 Paolo Maldini, to whom he had already Distribution of UEFA Report from Brussels 13 presented the UEFA President’s Prize Champions League revenue 06 the evening before. News from member PHOTO: ANTONIO LINGRIA AC Milan win the UEFA Super Cup 07 associations 17 FromEditorial strength to strength Nowadays, it is not enough just to launch a top-rate sporting competition; it has to also be given the right environment for guaranteeing its popularity and commercial success. There is no doubt that the careful way in which the UEFA Champions League has been promoted has had a significant impact on its success. Thanks to its distinctive identity, the use of the same visual effect in all the stadiums, a strict marketing concept and quality broadcasting, the UEFA Champions League has established itself as a prime example in the world of sport. This season, the competition has a new format and we have also decided to strengthen its public image. For this purpose, we are introducing enhanced branding and a new consumer magazine, “Champions”, through which football fans throughout Europe can find out more about the competition and all those involved in it. Our new media experts are also strengthening the presence of the UEFA Champions League via the uefa.com website. -

Sweden U19 Queens of Europe WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL No

Sweden U19 queens of Europe WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL No. 120 | August 2012 In This issue Official publication of the Union des associations Qualifiers for ThE 2014 WORLd CUp 4 européennes de football All 53 UEFA national associations will be in the starting lineup in September for one of the 13 places up for grabs for European teams in the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, Images Chief editor : including the title holders, Spain. André Vieli Getty Produced by : Atema Communication SA, CH-1196 Gland Printing : AnothER TITLE for SpAIn 6 Artgraphic Cavin SA, CH-1422 Grandson Spain claimed their sixth European title at U18/19 level with victory in Estonia. Editorial deadline : 9 August 2012 Sportsfile The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily SWEdEn WIn ThE WOmEn’S UndER-19 the official views of UEFA. The reproduction of articles ChAmpIOnShIp 8 published in UEFA·direct By beating Spain in the final in Antalya (Turkey), Sweden is authorised, provided the source is indicated. won the European Women’s U19 title for the first time. Sportsfile dEmOnstrating social RESpOnSIBILITy 11 EURO 2012 in Poland and Ukraine was not only a huge feast of European football: it was also a chance for football to show solidarity with less fortunate members of society. Empics SOLIdARITy pAymEnTS for yOUTh dEvelopmEnT progRAmmES 12 The revenue from the UEFA Champions League also goes towards developing young players at top-division clubs, with Sport more than €70 million being allocated to clubs across Europe from the 2011/12 competition. Empics nEWS from mEmBER associationS 14 Cover: In Turkey, Sweden won their first European Women’s Under-19 title, having previously won the competition in 1999, when it was an Under-18 event Photo: Sportsfile 2 | UEFA •direct | 08.12 Editorial UEFA Never A dull mOmEnT Though a wonderful UEFA EURO 2012 is Furthermore, to ensure that all cases are dealt barely over and still fresh in our memories, the with to the highest legal standards, the UEFA pulse of football continues to beat strong. -

O Guia Dos Curiosos Copas.Pdf

Marcelo Duarte Marcelo Duarte e as no gu rm e a s s o r d v o i l ACORDO n e o t v s ORTOGRÁFICO o E © Marcelo Duarte Diretor editorial Projeto gráfico Reportagem Marcelo Duarte Mariana Bernd Gustavo Longhi de Carvalho Diretora comercial Diagramação Colaboração Patty Pachas Camila Sampaio Júlia Bezerra Neto Galuban Diretora de projetos especiais Ilustração do título Marcos Oshima Tatiana Fulas Arthur Carvalho Revisão Coordenadora editorial Ilustração da capa Carmen T. S. Costa Vanessa Sayuri Sawada Stefan Juliana de Araujo Rodrigues Sérgio Miranda Paz Assistentes editoriais Ilustradores Lucas Santiago Vilela Junião Impressão Mayara dos Santos Freitas Marco Carillo Cromosete Moa Assistentes de arte Stefan Carolina Ferreira Hellen Cristine Dias Mario Kanegae Parte do material deste livro foi anteriormente publicada em O Guia dos Curiosos – Esportes, de Marcelo Duarte. CIP-BRASIL. CATALOGAÇÃO NA PUBLICAÇÃO SINDICATO NACIONAL DOS EDITORES DE LIVROS, RJ Duarte, Marcelo, 1964- O Guia dos Curiosos: Copas / Marcelo Duarte. – 1. ed. – São Paulo: Panda Books, 2014. 420 pp. Inclui bibliografia ISBN 978-85-7888-355-3 1. Copas do Mundo (Futebol) – História. 2. Futebol – Brasil – História. I. Título. 14-10418 CDD: 796.334 CDU: 79.332 2014 Todos os direitos reservados à Panda Books Um selo da Editora Original Ltda. Rua Henrique Schaumann, 286, cj. 41 05413-010 – São Paulo – SP Tel./ Fax: (11) 3088-8444 [email protected] www.pandabooks.com.br twitter.com/pandabooks Visite também nossa página no Facebook. Nenhuma parte desta publicação poderá ser reproduzida por qualquer meio ou forma sem a prévia autorização da Editora Original Ltda. -

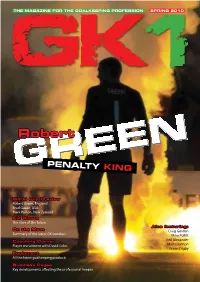

GK1 - FINAL (4).Indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02

THE MAGAZINE FOR THE GOALKEEPING PROFESSION SPRING 2010 Robert PENALTY KING World Cup Preview Robert Green, England Brad Guzan, USA Mark Paston, New Zealand Kid Gloves The stars of the future Also featuring: On the Move Craig Gordon Summary of the latest GK transfers Mike Pollitt Coaching Corner Neil Alexander Player recruitment with David Coles Matt Glennon Fraser Digby Equipment All the latest goalkeeping products Business Pages Key developments affecting the professional ‘keeper GK1 - FINAL (4).indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02 BPI_Ad_FullPageA4_v2 6/2/10 16:26 Page 1 Welcome to The magazine exclusively for the professional goalkeeping community. goalkeeper, with coaching features, With the greatest footballing show on Editor’s note equipment updates, legal and financial earth a matter of months away we speak issues affecting the professional player, a to Brad Guzan and Robert Green about the Andy Evans / Editor-in-Chief of GK1 and Director of World In Motion ltd summary of the key transfers and features potentially decisive art of saving penalties, stand out covering the uniqueness of the goalkeeper and hear the remarkable story of how one to a football team. We focus not only on the penalty save, by former Bradford City stopper from the crowd stars of today such as Robert Green and Mark Paston, secured the All Whites of New Craig Gordon, but look to the emerging Zealand a historic place in South Africa. talent (see ‘kid gloves’), the lower leagues is a magazine for the goalkeeping and equally to life once the gloves are hung profession. We actively encourage your up (featuring Fraser Digby). -

FIFA World Cup™ Is fi Nally Here!

June/July 2010 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE | Team profi les | Star players | National hopes | South Africa’s long journey | Leaving a legacy | Broadcast innovations | From Montevideo to Johannesburg | Meet the referees | Team nicknames TIME FOR AFRICA The 2010 FIFA World Cup™ is fi nally here! EDITORIAL CELEBRATING HUMANITY Dear members of the FIFA family, Finally it has arrived. Not only is the four-year wait for the next FIFA World Cup™ almost over, but at last the world is getting ready to enjoy the fi rst such tournament to be played on African soil. Six years ago, when we took our most prestigious competition to Africa, there was plenty of joy and anticipation on the African continent. But almost inevitably, there was also doubt and scepticism from many parts of the world. Those of us who know Africa much better can share in the continent’s pride, now that South Africa is waiting with its famed warmth and hospitality for the imminent arrival of the world’s “South Africa is best teams and their supporters. I am convinced that the unique setting of this year’s tournament will make it one of the most waiting with its memorable FIFA World Cups. famed warmth and Of course we will also see thrilling and exciting football. But the fi rst-ever African World Cup will always be about more than just hospitality, and I am the game. In this bumper double issue of FIFA World, you will fi nd plenty of information on the competition itself, the major stars convinced that the and their dreams of lifting our famous trophy in Johannesburg’s unique setting of this spectacular Soccer City on 11 July.