The Odo Masquerade Institution and Tourism Development: a Case Study of Igbo- Etiti Local Government Area of Enugu State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

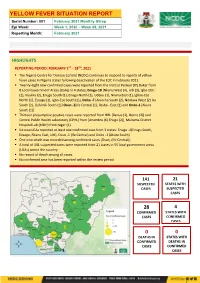

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021 HIGHLIGHTS REPORTING PERIOD: FEBRUARY 1ST – 28TH, 2021 ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) continues to respond to reports of yellow fever cases in Nigeria states following deactivation of the EOC in February 2021. ▪ Twenty -eight new confirmed cases were reported from the Institut Pasteur (IP) Dakar from 8 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in 4 states; Enugu-18 [Nkanu West (4), Udi (3), Igbo-Etiti (2), Nsukka (2), Enugu South (1), Enugu North (1), Udenu (1), Nkanu East (1), Igboe-Eze North (1), Ezeagu (1), Igbo-Eze South (1)], Delta -7 [Aniocha South (2), Ndokwa West (2) Ika South (2), Oshimili South (1)] Osun -2[Ife Central (1), Ilesha - East (1) and Ondo-1 [Akure South (1)] ▪ Thirteen presumptive positive cases were reported from NRL [Benue (2), Borno (2)] and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) from [Anambra (6) Enugu (2)], Maitama District Hospital Lab (MDH) from Niger (1) ▪ Six new LGAs reported at least one confirmed case from 3 states: Enugu -4(Enugu South, Ezeagu, Nkanu East, Udi), Osun -1 (Ife Central) and Ondo -1 (Akure South) ▪ One new death was recorded among confirmed cases [Osun, (Ife Central)] ▪ A total of 141 suspected cases were reported from 21 states in 55 local government areas (LGAs) across the country ▪ No record of death among all cases. ▪ No confirmed case has been reported within the review period 141 21 SUSPECTED STATES WITH CASES SUSPECTED CASES 28 4 -

Federal Government of Nigeria 2011 Budget Federal Ministry of Land and Housing

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2011 BUDGET SUMMARY FEDERAL MINISTRY OF LAND AND HOUSING TOTAL PERSONNEL TOTAL OVERHEAD TOTAL TOTAL CODE MDA COST COST RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL ALLOCATION =N= =N= =N= =N= =N= MINISTRY OF LANDS & 0250001 HOUSING 3,137,268,528 418,458,068 3,555,726,596 33,147,994,158 36,703,720,754 TOTAL 3,137,268,528 418,458,068 3,555,726,596 33,147,994,158 36,703,720,754 27,227,159,376 15,086,283,689 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LAND AND HOUSING: 1 2011 AMENDMENT APPROPRIATION FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2011 AMENDMENT APPROPRIATION CODE LINE ITEM (=N=) TOTAL: MINISTRY OF LANDS & HOUSING 36,703,720,754 TOTAL ALLOCATION: 36,703,720,754 21 PERSONNEL COST 3,137,268,528 2101 SALARY 2,789,977,780 210101 SALARIES AND WAGES 2,789,977,780 21010101 CONSOLIDATED SALARY 2,789,977,780 2102 ALLOWANCES AND SOCIAL CONTRIBUTION 347,290,748 210202 SOCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS 347,290,748 21020201 NHIS 138,916,299 21020202 CONTRIBUTORY PENSION 208,374,449 22 TOTAL GOODS AND NON - PERSONAL SERVICES - GENERAL 418,458,068 2202 OVERHEAD COST 418,458,068 220201 TRAVEL& TRANSPORT - GENERAL 138,312,778 22020101 LOCAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: TRAINING 29,251,947 22020102 LOCAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: OTHERS 58,059,000 22020103 INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: TRAINING 24,496,875 22020104 INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: OTHERS 26,504,956 220202 UTILITIES - GENERAL 13,136,994 22020201 ELECTRICITY CHARGES 6,237,000 22020202 TELEPHONE CHARGES 3,534,300 22020203 INTERNET ACCESS CHARGES 900,000 22020205 WATER RATES 1,945,944 22020206 SEWERAGE CHARGES 519,750 220203 MATERIALS & -

WOMEN and Elecnons in NIGERIA: SOME EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE from the DECEMBER 1991 Elecnons in ENUGU STATE

64 UFAHAMU WOMEN AND ELEcnONS IN NIGERIA: SOME EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FROM THE DECEMBER 1991 ELEcnONS IN ENUGU STATE Okechukwu lbeanu Introduction Long before "modem" (Western) feminism became fashionable, the "woman question" had occupied the minds of social thinkers. In fact, this question dates as far back as the Judeo-Christian (Biblical) notion that the subordinate position of women in society is divinely ordained. • Since then, there have also been a number of biological and pseudo-scientific explanations that attribute the socio-economic and, therefore, political subordination of women to the menfolk, to women's physiological and spiritual inferiority to men. Writing in the 19th century, well over 1,800 years A. D., both Marx and Engels situate the differential social and political positions occupied by the two sexes in the relations of production. These relations find their highest expression of inequality in the capitalist society (Engels, 1978). The subordination of women is an integral part of more general unequal social (class) relations. For Marx, "the degree of emancipation of women is the natural measure of general emancipation" (Vogel, 1979: 42). Most writings on the "woman problematique" have generically been influenced by the above perspectives. However, more recent works commonly emphasized culture and socialization in explaining the social position of women. The general idea is that most cultures discriminate against women by socializing them into subordinate roles (Baldridge, 1975). The patriarchal character of power and opportunity structures in most cultures set the basis for the social, political and economic subordination of women. In consequence, many societies socialize their members into believing that public life is not for the female gender. -

Niger Delta Budget Monitoring Group Mapping

CAPACITY BUILDING TRAINING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT & SHADOW BUDGETING NIGER DELTA BUDGET MONITORING GROUP MAPPING OF 2016 CAPITAL PROJECTS IN THE 2016 FGN BUDGET FOR ENUGU STATE (Kebetkache Training Group Work on Needs Assessment Working Document) DOCUMENT PREPARED BY NDEBUMOG HEADQUARTERS www.nigerdeltabudget.org ENUGU STATE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) COMMISSION S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Teaching and Learning 40,000,000 Enugu West South East New Materials in Selected Schools in Enugu West Senatorial District 2 Construction of a Block of 3 15,000,000 Udi Ezeagu/ Udi Enugu West South East New Classroom with VIP Office, Toilets and Furnishing at Community High School, Obioma, Udi LGA, Enugu State Total 55,000,000 FGGC ENUGU S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Construction of Road Network 34,264,125 Enugu- North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Enugu South 2 Construction of Storey 145,795,243 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Building of 18 Classroom, Enugu South Examination Hall, 2 No. Semi Detached Twin Buildings 3 Purchase of 1 Coastal Bus 13,000,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East Enugu South 4 Completion of an 8-Room 66,428,132 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Storey Building Girls Hostel Enugu South and Construction of a Storey Building of Prep Room and Furnishing 5 Construction of Perimeter 15,002,484 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Fencing Enugu South 6 Purchase of one Mercedes 18,656,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Water Tanker of 11,000 Litres Enugu South Capacity Total 293,145,984 FGGC LEJJA S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. -

Enugu State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed

RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) Public Disclosure Authorized ENUGU STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) Public Disclosure Authorized FOR THE 9TH MILE GULLY EROSION SUB-PROJECT INTERVENTION SITE Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) ENUGU STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) FOR THE 9TH MILE GULLY EROSION SUB-PROJECT INTERVENTION SITE FINAL REPORT Submitted to: State Project Management Unit Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) Enugu State NIGERIA NOVEMBER 2014 Page | ii Resettlement Action Plan for 9th Mile Gully Erosion Site Enugu State- Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF PLATES ...................................................................................................................................................................... v DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Basic Objective of Theprograms Described Is to Implement the Concept Descriptions Include How Each Program, Focusing on a Well-D

DOCUNENT RESUME - BD 140 072 cE 011 482 AUTHOR Odokara, E.O. TITLE Outreach: University's Concern for Communities Around' It. :INSTITUTION Nigeria Univ., Nsukka. Div. of Extra-Mu al Studies. PUB DATE (76) ROTE 73p. EDRS PRICE Mf-$0.83 Hc-$3.5,0 Plus Pos age. DESCRIPTORs Adult Education; Community Education; Community Services; *Extension Education; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Haman Development; Human Resources; *Individual Needs; Occupational Guidance; *Outreach Programs; *Program DescriptiOns; Resource Materials; Rural Areas; *School Community Programs; Urban Areas; Vocational Education IDENTIFIE ES *Nigeria; University of Nigeria .ABSTRACT Extension, or outreach, programs initiated and conducted through the Division of Extramural Studies at the :University of Nigeria (Nsukka) are desCribed in this booklet. The basic objective of theprograms described is to implement the concept 4:)f education as a continuing, lifelong, and dynamic process through which adults (younger and older) can lead more meaningful and useful lives, and through which the communities concerned can improve their functioning. Programs included are characterized under one of three .groups: Community study groups, awareness forum, or outreach. The descriptions include how each program, focusing on a well-define& target population, relates to its specific educational objective(s). (SH) * Documents acquired by.ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes everyeffort * * to obtain the beSt copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reprOducibility are often encountered and thi8 affects thequality * * of tle microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makesavailable * via theERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied by.EDRS'are.the best that can be made from the original. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Sources of Information on Climate Change Among Crop Farmers in Enugu North Agricultural Zone, Nigeria

International Journal of Research in Agriculture and Forestry Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2015, PP 27-33 ISSN 2394-5907 (Print) & ISSN 2394-5915 (Online) Sources of Information on Climate Change among Crop Farmers in Enugu North Agricultural Zone, Nigeria Akinnagbe O.M1, Attamah C.O2, Igbokwe E.M2 1Department of Agricultural Extension and Communication Technology, Federal ,University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria) 2Department of Agricultural Extension, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria) ABSTRACT The study ascertained the sources of information on climate change among crop farmers in Enugu north agricultural zone of Enugu State, Nigeria. A multi-stage sampling technique was employed in selection of 120 crop farmers. Data for this study were collected through the use of structured interview schedule. Percentage, charts and mean statistic were used in data analysis and presentation of results. Findings revealed that majority of the respondents were female, married, and literate, with mean age of 38.98 years. The major sources of information on climate change were from neighbour (98.3%), fellow farmers (98.3%) and family members (98.3%). Among these sources, the major sources where crop farmers received information on climate change regularly were through fellow farmers (M=2.15) and neighbour (M=2.12). Since small scale crop farmers received and accessed climate change information from fellow farmers, neighbour and family members, there is need for extension agents working directly with contact farmers to improve on their service delivering since regular and timely information on farmers farm activities like the issue of climate change is of paramount important to farmers for enhance productivity Keywords: Information sources, climate change, crop farmers. -

P. 126 – 135 (ISSN: 2276-8645) TREND

International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews Vol.11 No.2, July 2021; p. 126 – 135 (ISSN: 2276-8645) TREND OF STUDENTS’ ENROLMENT AND TEACHER ADEQUACY IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN ENUGU STATE SOUTH-EAST NIGERIA ONU, AGATHA NGOZI School of General Studies Department of Social Sciences Federal Polytechnics Oko. [email protected] +2347060999490 ABSTRACT The study investigated trend of students’ enrolment in secondary schools for 2013/14 to 2017/18 academic sessions in Enugu State South-East Nigeria. The design of the study was descriptive design. The population of the study was all the students and teachers in government owned secondary schools; numbering 129,317 and 7945 of students, and teachers respectively for the 17 LGAs in Enugu State. There was no sample; hence the entire population was used for the study. The instrument for data collection was checklist on Trend of Students’ Enrolment and Teacher Adequacy in Enugu State Secondary Schools (TOSETA). Face validation was effected by two experts in educational administration and in measurement and evaluation, all in the faculty of education, ABSU. No reliability test was conducted since the records for the study came from secondary school management board of the state of study. The researcher with the help of (1) assistant in the statistical division of the secondary school board administered the instrument. Data were analysed using mean and percentage. It was found that the trend in students’ enrolment in Enugu State Secondary Schools showed significant decrease during the period under study. It was also found that in absolute terms, the growth rate showed that girls enrolled more than boys. -

Geoelectrical Sounding for Estimating Groundwater Potential in Nsukka L.G.A

International Journal of the Physical Sciences Vol. 5(5), pp. 415-420, May 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPS ISSN 1992 - 1950 © 2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Geoelectrical sounding for estimating groundwater potential in Nsukka L.G.A. Enugu State, Nigeria Chukwudi C. Ezeh1* and Gabriel Z. UGWU2 1Department of Geology and Mining, Enugu State University of Science and technology, Enugu, Nigeria. 2Department of Industrial Physics, Enugu State University of Science and technology,Enugu, Nigeria. Accepted 15 April, 2010 Sixty six vertical electrical soundings (VES) have been used to evaluate the ground water potential in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria. The project domain lies within longitudes 7°1300 - 7°3530 and latitudes 6°4330 - 7°0030 and covers an area of about 480 km² over three main geological formations. The resistivity and thickness of the aquiferous layer at various observation points were determined by the electrical survey. Also zones of high yield potentials were inferred from the resistivity information. Transmissivity values were inferred using the calculated Dar Zarrouk parameters. Results show highly variable thickness of the aquiferous layer in the study area. Aggregate transverse resistance indicates greater depth of the substratum in the southeastern part of the study area, underlain mostly by the Ajali Formation. High values of transmissivity also predominate, thus suggesting thick and prolific aquiferous zone. Key words: Resistivity, transverse resistance, transmissivity. INTRODUCTION Nsukka Local Government Area lies between longitudes and exploitation in the area. 7°1300 - 7°3530 and latitudes 6°4330 - 7°0030 in Enugu State, Southeastern Nigeria. -

Ezeonu Et Al., Afr., J. Infect. Dis. (2021) 15 (2): 24-30 V15i2.5

Ezeonu et al., Afr., J. Infect. Dis. (2021) 15 (2): 24-30 https://doi.org/10.21010/ajid v15i2.5 PREVALENCE OF TUBERCULOSIS, DRUG-RESISTANT TUBERCULOSIS AND HIV/TB CO-INFECTION IN ENUGU, NIGERIA. Kennethe Okonkeo Ugwu†, Martin Chinonye Agbo†† and Ifeoma Maureen Ezeonu†* †Department of Microbiology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria ††Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Biotechnology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka *Corresponding Author’s E-mail: [email protected] Article History Received: 1st June 2020 Revised Received: 25th Jan 2021 Accepted: 29th Jan 2021 Published Online: 18th March 2021 Abstract Background: Tuberculosis (TB) remains a global public health problem, with developing countries bearing the highest burden. Nigeria is first in Africa and sixth in the world among the countries with the highest TB burden, but is among the 10 countries accounting for over 70% of the global gap in TB case detection and notification. Enugu State, Nigeria reportedly has a notification gap of almost 14,000 TB cases; a situation which must be addressed. Materials and Methods: A total number of 868 individuals accessing DOTS services in designated centres within the six Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Enugu North geographical zone, was recruited into the study. The participants were screened for HIV seropositivity by standard protocols, while screening for TB and drug-resistant TB were conducted by a combination of Zhiel Neelsen staining and Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (Xpert® MTB/Rif). Results: Of the 868 subjects that participated in the study, 176 (20.3%) were HIV seropositive. The highest prevalence (26.7%) of HIV was recorded in Udenu LGA, while the least (13.1%) was recorded in Nsukka LGA. -

The Case of Uzo-Uwani Local Government Area

Animal Research International (2004) 1(1): 57 – 63 57 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION IN THE CONTROL OF PARASITIC DISEASES: THE CASE OF UZO-UWANI LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA UBACHUKWU, Patience Obiageli Department of Zoology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. ABSTRACT A study on the epidemiology and effects of human onchocerciasis on productivity and social lives of rural communities in Uzo-Uwani Local Government Area of Enugu State was carried out between 1998 and 2000. The objectives of the study were to assess the level of endemicity of onchocerciasis in the 16 communities that make up the local government area and to ascertain the effects of the disease on the pattern of social interactions and the age of marriage of the infected individuals. The work also involved the local disease perception and treatment of the disease in the area and histopathological studies of the Onchocerca nodules. In the course of the studies, interviews were conducted for individuals and various groups in the communities including the Community Directed Distributors (CDDs) of ivermectin in the area. During these interactions, a number of problems that beset the control of onchocerciasis in the area became obvious. This paper reports on the community participation in the control of the disease, the problems encountered by these rural people in their efforts (which include lack of funds, late arrival of drugs, transportation and communication problems) and makes recommendations on how to overcome some of these problems. Key words: Epidemiology, onchocerciasis, productivity, Community Directed Distributors, Control. INTRODUCTION 4. its ability to bring about a dramatic reduction in the skin microfilarial load and potentially Control of onchocerciasis had depended largely to reduce the morbidity and on the control of vectors by means of 5.