The Sociological Dimension of Concrete Interiors During the 1960S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Pinte Van Het Café Naar Het Gemeentehuis

WIJ GEVEN DUOTICKETS DE PINTE EN BOEKEN VAN HET CAFÉ NAAR WEG HET GEMEENTEHUIS JAARGANG 8 | DECEMBER 2019 POLSCULTUUR-SLAG EN ERFGOEDMAGAZINE VOOR DE LEIE- EN SCHELDESTREEK DEINZE DE PINTE GAVERE NAZARETH SINT-MARTENS-LATEM ZULTE PAG 3 POLSSLAG INHOUD 13-16 Kalender 3 Nieuwe raad van bestuur voor POLS 17 85ste autowijding (vervolg) 4 De nieuwe Cultuurregio Leie Schelde 18-19 Van het café naar het gemeentehuis NIEUWE RAAD VAN BESTUUR VOOR 5-7 Paul Kongs in de kijker 20-21 50 jaar Heemkring Scheldeveld 100 jaar Vredesfeesten 8-11 21-22 Gloednieuw cultureel centrum in Deinze n 2013 werd projectvereniging POLS boven ste 12 85 autowijding 24 In memoriam: Juliaan Lampens de doopvont gehouden. De vereniging spitst zich toe op erfgoed en cultuurcommunicatie. Het werkgebied van POLS omvat I6 gemeenten (Deinze, De Pinte, Gavere, Nazareth, ZULTE Sint-Martens-Latem en Zulte). Onze organisatie GROTE VOORJAARS- wordt geleid door een Raad van Bestuur met TENTOONSTELLING KUNSTENAAR vertegenwoordigers uit die zes gemeentes. MARTIN WALLAERT POLS In de Dorpsstraat 48, in villa Ter Ide, is er het nieuwe atelier (geopend op 20 oktober 2019) van de nog levende kunstenaar Martin Wallaert. Wanneer Je kan er een kijkje nemen in de leefwereld en het atelier van de Zaterdag 11 april t.e.m. Pinkstermaandag kunstenaar en zijn werken (her)ontdekken. Verder kan je hem ook 1 juni 2020 persoonlijk ontmoeten. Villa Ter Ide is een art-deco woning uit de jaren 1920 met heel wat Waar originele, unieke elementen en een lichtrijk atelier. Villa Ter Ide, atelier Martin Wallaert, De toegang tot het atelier, waar nog elke dag gecreëerd wordt, is Dorpsstraat 48, 9870 Machelen-aan-de-Leie mogelijk op zondagnamiddag tussen 14.00 en 18.00 uur en is vrij. -

Acicek Cv.Pdf

Dipl. Ing. Aslı Çiçek CV Adress Avenue Albert 2, D12 BE- 1190 Brussels Mobile phone +32.484.634.828 Office phone +32.2.356.31.66 E-mail address [email protected] Website www.aslicicek.eu Born 22 / 03 / 1978, Istanbul / TR Nationality Turkish and Belgian Languages Turkish (native), German (bilingual proficiency), English (full professional proficiency), Dutch (professional working proficiency), French (elementary proficiency) Education 1998- 2004 Academy of Fine Arts, Munich / DE, Architecture and Design Department, MA 1989- 1997 Istanbul Lisesi, high school with German and Turkish curriculum, graduated with high honours in natural sciences (LK Physik und Mathematik), Istanbul / TR 1984 - 1989 Namık Kemal Primary School, Istanbul / TR Projects 2020 Renovation and interior of an apartment, Brussels / BE, in design phase. Werkplaats. IABR Atelier Ost- Vlaams Kerngebied, Ghent / BE Exhibition design for research projects on East Flanders, STAM spring 2020 (postponed) Interiors of BiiP offices, Leuven / BE. In a project of T’Jock Nillis architecten, in execution. 2019 Competition project for the extension of Groeninge Abdij Kortrijk, Open Call 0038, with fala architects. Constantin Brancusi. Europalia 2019 Romania, Brussels / BE. Exhibition architecture of the opening show of the festival, BOZAR 10 / 10 / 2019 - 02 / 02 / 2020. Z33 International House for Contemporary Art, Hasselt / BE. Opening exhibition of the new museum’s building. March 2020. A School of Schools. C-Mine Genk, Brussels / BE. Exhibition architecture through industrial halls, with 3+1 structures, on exhibiting works of social design. 28 / 06 - 02 / 09 /2019. A School of Schools. LUMA Art Foundation, Arles / FR. Exhibition architecture with 3+1 structures. 28 / 04 - 29 / 05 / 2019. -

Jvdb Cv-RMIT

Jo Van Den Berghe Ph.D Curriculum Vitae [1961]. Teaches experimental architectural design in M.Arch 1 at Leuven University Faculty of Architecture, Campus Sint-Lucas Brussels/Ghent, Belgium Professor of Architecture at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University, Barcelona, Spain. Researcher in the field of Techné and Poiesis in making architecture. Reflective practitioner-architect since 1987, with a critical architectural practice in Belgium. 1. Facts 2013 Ph.D Architecture, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia (see attachment). 2009 RTS (Research Training Sessions), Doctoral School Program, Sint-Lucas School of Architecture, Brussels/Ghent, Belgium (see attachment). 1986-2015 Architectural practice. 1984-86 Internship at Juliaan Lampens Architect, Eke, Belgium. 1984 Master of Architecture, Sint-Lucas School of Architecture, Ghent, Belgium (see attachment). 1979 Secondary School, Latin-Mathematics, College, Zottegem, Belgium. 2. Exhibitions 2015/03-04 ETH Zürich, GTA Exhibitions, Carousel, with House DGDR, curators Jan De Vylder, Christel Vinck and Jo Taillieu. 2014/10/15 VAI (Vlaams Architectuurinstituut), DeSingel, De Provocatie van het Schijnbaar Onmogelijke (The Provocation of the Apparently Impossible), in collaboration with Mira Sanders, exhibition architectural research in architectural education in the exhibition series ‘Projecties’. 2014/04/09 The Anatomical Drawing, University College Dublin. 2013/04 Ph.D Exhibition, RMIT Campus, Barcelona, Spain. 2012/11-12 Theatre of Operations, Ph.D Exhibition, University Library (Henry Van de Velde), Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. 2012/11 Dessa Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia: The Boathouse 1 and The Boathouse 2, curator Leon Van Schaik. 2012/08 Venice Biennale, Australian Pavilion, Venice, Italy: The Boathouse 1 and The Boathouse 2. 2011/11 Installation for the Graduate Research Conference, Sint-Lucas School of Architecture, Ghent, Belgium. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Overzicht activiteiten van 1974 tot december 2018. Marc Dubois (Oostende, 13 oktober 1950) Firmin De Maître / C.V. Maîtrise Tekening Álvaro Siza Vieira / 2009 Adres B - Holstraat 89, 9000 GENT Tel. 09/225.02.16 GSM 0475/49.27.47. e-mail: [email protected] www.marcdubois.be December 2018 1 INHOUD Algemene informatie / Diploma’s, aanstellingen, enz. Medewerking aan overzichtswerken Publicatie boeken Hoofdredacteur themanummers Vlaanderen Artikels in boeken Artikels in tijdschriften Artikels in Knack Artikels in dagbladen Artikels in digitale vorm Lid jury bijeenkomsten Tentoonstellingen Lezingen / nationaal & internationaal. Lezingen internationaal (overzicht) Studiereizen 2012 t/m 2017 2 Architectuurstudies aan het Hoger Architectuurinstituut Sint Lucas Gent, afstudeerjaar 1974 Van 1975 tot 1977 stage in Gent en Oostende (architect Marcel Molleman) Van 1978 tot 1980 werkzaam als zelfstandig architect Onderwijsopdrachten In 1978 assistent aan het Hoger Architectuurinstituut Sint Lucas Gent Van 1984 tot 1990 secretaris CAO (Centrum voor Architectuuronderzoek Sint Lucas Gent) Hoofdredacteur tijdschrift CAO Tijdingen Sint Lucas (1984-1990) Sinds 1991 werkleider, sinds 1995 docent Nadien hoofddocent tot oktober 2015 Emeritaat oktober 2015. Van 1980 tot 1983 lesgever aan het Nationaal Hoger Instituut voor Bouwkunst en Stedebouw te Antwerpen (nu Henry van de Velde Instituut), vak architectuurgeschiedenis Buitenlandse onderwijsopdrachten Van 1996 tot 2008 docent aan het Piet Zwart Instituut, Willem De Kooning Academie van -

Juliaan Lampens, Nazareth (België) Authentiek Modernisme Van Vlaamse Bodem

Juliaan Lampens, Nazareth (België) Authentiek modernisme van Vlaamse bodem Local Heroes #05 Juliaan Lampens 1926-heden Door Coen Smit, aug 2011 fot o’s: Jörn Schiemann, Annema- rijn Haarink, Coen Smit en Geurt Holdijk. Joost Hovenier (Appendix blz 17) English text on page 12 Local Heroes is een initiatief van Office Winhov Kort van de snelweg N60, even na het dorp Ou- denaarde, onder Gent, draaien we de Edelareberg op. Het is 10 uur s’ochtends en nog erg rustig op de weg. Mis- schien toch maar even de weg vragen. Bij het openen van het portier, voel en ruik je het; hier beginnen de Vlaamse Ardennen. Een groepje gekromde renners geeft nog eens een bevestiging. De Edelareberg, een helling die 35 maal onderdeel was van de Ronde van Vlaanderen, Kuurne- Brussel-Kuurne, Dwars door Vlaanderen, de Driedaagse van De Panne-Koksijde en Nokere Koerse. U zal wel denken. De titel van deze uitgave van Lo- cal Heroes wekt een andere indruk, of is deze editie toch geheel geweid aan de Belgische wielersport? En dan.. na een klim van 1500 meter met een gemiddeld stijgingsper- centage van 4,6% op de top van de berg, staan we aan de start van een dag vol beton, puurheid en detail. De bede- vaartskapel O.L.V. Van Kesselare in Edelare van Juliaan Lampens. Juliaan Lampens (°1926) is afkomstig van de De Pinte bij Gent. Hij stamt uit een ambachtelijk gezin. Van zijn vader, hij is schrijnwerker, erft hij een scherpe zin voor ambachtelijke degelijkheid. Al in zijn jeugd heeft hij een uitgesproken talent voor tekenen en droomt hij ervan om schilder te worden. -

EXCURSIE BELGIË APRIL 2010 9 April 2010 | Dag 1 | Gent En Omstreken Programma

EXCURSIE BELGIË APRIL 2010 9 april 2010 | dag 1 | Gent en omstreken programma 09.00 vertrek Breda 11.00 aankomst Gent 1 les Ballets C de la B - LOD 12.00 vertrek Gent 13.15 aankomst Menen 2 Stadhuis te Menen 14.15 vertrek Menen 15.15 aankomst Oudenaarde 3 Kapel Onze Lieve Vrouw van Kerselare 16.00 vertrek Oudenaarde 16.30 aankomst Eke / Nazareth 4 woonhuis Juliaan Lampens 17.15 vertrek Eke / Nazareth 17.30 aankomst Sint-Martens-Latem 5/6 woonhuis Van Wassenhove / woonhuis Van Boogaard 18.30 vertrek Sint-Martens-Latem 19.30 aankomst Brussel routing 09.00 vertrek Breda 11.00 aankomst Gent Les Ballets C de la B Breda naar Gent, België - Google Maps http://maps.google.nl/maps?q=breda%20gent&oe=utf-8&rls=... Bijlokekaai 1 B - 9000 Gent tel +32 9 2217501 Klik op de link "Afdrukken" naast de kaart om alle details op het scherm weer te geven. www.lesballetsdela.be Routebeschrijving Mijn kaarten Afdrukken Verzenden Link ©2010 Google - Kaartgegevens ©2010 Tele Atlas - Routebeschrijving naar Gent, België Breda 1. Vertrek in oostelijke richting op de Reigerstraat naar Grote Markt 0,1 km 2. Sla linksaf bij Kasteelplein 94 m 3. Sla linksaf bij Cingelstraat 0,2 km 4. Neem de 1e afslag rechts, de Kraanstraat op 68 m 5. Sla linksaf om op de Kraanstraat te blijven 29 m 6. Neem de 1e afslag rechts, de Hoge Brug op 54 m 7. Neem de 1e afslag links, de Gedempte Haven op 0,2 km 8. Weg vervolgen naar Markendaalseweg 0,4 km 9. -

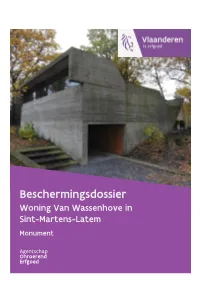

Beschermingsdossier

Beschermingsdossier Woning Van Wassenhove in Sint-Martens-Latem Monument Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed Beschermingsdossier: Woning Van Wassenhove, Sint-Martens-Latem, Brakelstraat 50 – monument INHOUDELIJK DOSSIER Dossiernummer: 4.001/44064/101.1 Katrijn Depuydt 2/05/2017 Pagina 2 van 21 Beschermingsdossier: Woning Van Wassenhove, monument INHOUDSTAFEL 1. Beschrijvend gedeelte ................................................................................... 4 1.1. Situering .................................................................................................. 4 1.2. Historisch overzicht ................................................................................... 4 1.3. Beschrijving met inbegrip van de erfgoedelementen en erfgoedkenmerken ....... 7 1.3.1. Ruimtelijke context ............................................................................. 7 1.3.2. Inplanting .......................................................................................... 7 1.3.3. Exterieur ............................................................................................ 7 1.3.4. Interieur ............................................................................................ 9 1.4. Fysieke toestand van het onroerend goed ...................................................12 2. Evaluerend gedeelte ....................................................................................13 2.1. Evaluatie van de erfgoedwaarden ...............................................................13 2.1.1. Juliaan Lampens – biografie -

Juliaan Lampens, Nazareth (Belgium) Authentic Modernism from Flemish Soil

Juliaan Lampens, Nazareth (Belgium) Authentic modernism from Flemish soil Local Heroes #05 Juliaan Lampens 1926-2019 By Coen Smit, Aug 2011 English translation by Menora Tse Photography: Jörn Schiemann, Annema- rijn Haarink, Coen Smit and Geurt Holdijk. Joost Hovenier Local Heroes is an initiative of Office Winhov Shortly after the N60 motorway, just after the vil- lage of Oudenaarde under Ghent, we turn onto the Edela- reberg. It is 10 o’ clock in the morning and it was still very quiet on the road. Perhaps just ask for directions. When you open the door, you feel it and smell it - this is where the Flemish Ardennes begin. A group of bent riders give further confirmation. The Edelareberg, a slope that has been part of the last 35 Tour of Flanders, Kuurne Brussels- Kuurne, across Flanders, Three Days of de Panne Koksijde and Nokere Koerse. Or so you thought. The title of this edition of Local Heroes gives a different impression: Is this edition entirely devoted to Belgian cycling? After a climb of 1500 meters with a 4.6% slope, we reach the summit and start the day full of concrete, purity and detail with the pilgrimage cha- pel O.L.V. van Kesselare in Edelare by Juliaan Lampens. Juliaan Lampens (1926) comes from De Pinte, near Ghent. Raised in a traditional family, he inherited a keen sense of craftsmanship from his carpenter father. Even in his youth he had a talent from drawing and dreamed of becoming a painter. At the advice of the village teacher, in 1940 he enrolled at the Higher Institute for Art and Pro- fessional Education in Sint-Lucas to train as a technical draftsman. -

MANIERA 16 Marie-José Van Hee in Collaboration with Marie Mees & Cathérine Biasino Curated by Katrien Vandermarliere

MANIERA 16 Marie-José Van Hee In collaboration with Marie Mees & Cathérine Biasino Curated by Katrien Vandermarliere 1 Dec 2017 – 24 Feb 2018 Preview Wednesday, 29 November Opening Thursday, 30 November Place de la Justice, 27–28 1000 Brussels MANIERA www.maniera.be [email protected] T + 32 (0) 494 787 290 © Crispijn Sas In early 2017, Marie-José Van Hee was awarded a prestigious International Fellowship by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) for her contribution to architecture. MANIERA turns the spotlight on this grande dame of Belgian architecture by showing her new and existing furniture. Marie-José’s architecture is tranquil and ascetic. In most of her designs for homes, furniture is an integral part of the space. Walls, stairs, galleries, they all hide cupboards, cloakrooms, workspaces, alcoves or bookcases. This gives rise to empty space that the occupants themselves can make use of. Free-standing pieces of furniture are composed of a limited number of materials and display the same elementary structural simplicity. They can also always be used for several purposes. MANIERA shows the existing bed-bank (bed/sofa) and the huis-werk-tafel (house/work/table), which are both the result of a design process lasting several years, alongside a new piece, the dien-blad-koffer (serving/tray/case). Marie-José invited Marie Mees and Cathérine Biasino to upholster the bed-bank and to domesticate the exhibition space. The textile designs by this Ghent duo, founders of the design label ThealfredCollection, are fully in keeping with Van Hee’s architecture. They show the same preference for natural materials, craftsmanship and tactile quality. -

06.14 BEHEERSPLAN Definitief Foto's Gecomprimeerd

dossier O6.14 : RESTAURATIE BEDEVAARTSOORD O.L.V. VAN KERSELARE opdrachtgever : kerkfabriek Onze Lieve Vrouw Geboorte te Pamele O. BEHEERSPLAN : blz. 1/224 BEHEERSPLAN ONROEREND ERFGOED O6.14 BEDEVAARTSOORD “O.L.V. VAN KERSELARE” te OUDENAARDE - EDELARE BEHEERSPLAN d.d. 26 juni 2O17 opgemaakt door architectuurstudio de schacht en partner(s) bv ovv bvba dossier O6.14 : RESTAURATIE BEDEVAARTSOORD O.L.V. VAN KERSELARE opdrachtgever : kerkfabriek Onze Lieve Vrouw Geboorte te Pamele O. BEHEERSPLAN : blz. 2/224 BEHEERSPLAN ONROEREND ERFGOED O6.14 BEDEVAARTSOORD “O.L.V. VAN KERSELARE” te OUDENAARDE - EDELARE ERFGOED : BEDEVAARTSOORD “O.L.V. VAN KERSELARE” LIGGING : KERZELARE 94, 97OO OUDENAARDE - EDELARE kadaster : OUDENAARDE, 6e afdeling, EDELARE, sectie A, nr. 162e BESCHERMINGSBESLUIT : Besluit : Besluit nummer 4648 Nummer(s) : 4.01/45035/300.1 / OO003381 Beschermd monument bij MB d.d. 2O november 2OO9 OPDRACHTGEVER : KERKFABRIEK Onze Lieve Vrouw Geboorte te Pamele contact : dhr. Jean Pierre OTTEVAERE, technisch raadgever PAMELEKERKPLEIN 3, 97OO OUDENAARDE telefoon : O475 . 42 48 11 ( technisch raadgever ) e-mail : [email protected] opgemaakt door : architectuurstudio de schacht & partner(s) bv ovv bvba contact : ir. arch. Freddy DE SCHACHT POEKESTRAAT 1, 8755 RUISELEDE telefoon : O51 . 68 96 75 e mail : [email protected] orde architecten provincie West – Vlaanderen voor het landschappelijk erfgoed in samenwerking met : buro voor vrije ruimte tuin- en landschapsarchitecten BVTL Christian Vermander – Thomas Van Mol & Partners RAAS VAN GAVERESTRAAT 67b, 9000 GENT telefoon : O9 . 225 56 65 e.mail : [email protected] BEHEERSPLAN d.d. 26 juni 2O17 BEHEERSPLAN d.d. 26 juni 2O17 opgemaakt door architectuurstudio de schacht en partner(s) bv ovv bvba dossier O6.14 : RESTAURATIE BEDEVAARTSOORD O.L.V.