'Battle of the Sixes': Investigating Print Media Representations of Female Pr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCOREBOARD Sports on TV A.M., ESPN2 Trenton Thompson

TimesDaily |Friday, June 7, 2019 D3 SPORTS ON TV/RADIO Today Super Regional, Game 1, 11 SCOREBOARD Sports on TV a.m., ESPN2 Trenton Thompson. Harold Varner III 33-35—68 AUTO RACING •NCAATournament: Florida PRO BASEBALL HORSE RACING Ryan Palmer 36-32—68 •FormulaThree: WSeries, State vs.LSU,Baton Rouge HOCKEY Kelly Kraft 35-33—68 MLB BELMONT ODDS National Hockey League Scott Stallings 34-34—68 Belgium (taped), 3p.m., NBCSN Super Regional,Game 1, 2p.m., All times Central The field for Saturday’s 151st Belmont Stakes, DALLAS STARS —Signed DRoman Polak Sepp Straka35-33—68 •ARCASeries: The Michigan ESPN AMERICAN LEAGUE with post position, horse, jockey and odds: and FMattais Janmark to one-year contract Kyle Jones 33-35—68 EAST DIVISION WLPCT.GB PP,HORSE JOCKEY ODDS extensions. Jim Knous 35-33—68 200, 5p.m., FS1 •NCAATournament: Stanford New York 39 22 .639 — 1. Joevia Jose Lezcano 30-1 Joey Garber 32-36—68 •NASCAR GanderOutdoors vs.Mississippi State, Starkville TampaBay 37 23 .617 1½ 2. Everfast Luis Saez 12-1 SOCCER Ryan Yip 35-33—68 Boston 33 29 .532 6½ 3. Master Fencer Julien Leparoux 8-1 Major League Soccer Ben Crane 35-34—69 Truck Series: The Rattlesnake Super Regional, Game 1, 2p.m., Toronto 23 39 .371 16½ 4. TaxIradOrtiz Jr. 15-1 MLS —Fined Portland Timbers MSebastian Trey Mullinax 35-34—69 George McNeill 37-32—69 400, 8p.m., FS1 ESPN2 Baltimore1943.306 20½ 5. Bourbon WarMikeSmith 12-1 Blanco and DLarrysMabiala for violating heads CENTRAL DIVISION WLPCT.GB 6. -

2020 Lpga Tour Player-Agent List (Updated 10/20/20)

2020 LPGA TOUR PLAYER-AGENT LIST (UPDATED 10/20/20) Active LPGA Tour Members NOT listed in this directory are independent members and can be contacted via email at [email protected]. Brittany Altomare Paula Creamer Kristen Gillman Jeff Stacy Jay Burton Kevin Hopkins Empire Sports Management IMG Excel Sports Management 216-630-0615 216-533-1775 973-975-3354 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Celine Boutier Katelyn Dambaugh Hannah Green Alina Pätz Jeff Stacy Jay Burton/Jonathan Chafe samm group Empire Sports Management IMG +41 79 502 77 56 216-630-0615 Burton: 216-533-1775 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Chafe: 330-703-3463 Sarah Burnham Laura Davies [email protected] JS Kang Vicky Cuming Epoch Sports Group IMG Jaye Marie Green 404-518-2002 011-44-776-851-7081 Matt Judy [email protected] [email protected] Blue Giraffe Sports 404-643-5952 Tiffany Chan Tony Davies [email protected] Jeremy Yew LD Sports Management [email protected] 011-44-7989-432641 Natalie Gulbis [email protected] Jay Burton Ssu-Chia Cheng IMG Connie Chen Austin Ernst 216-533-1775 909-213-4179 Rachel Everett [email protected] [email protected] Everett Sports Management 864-350-1222 Georgia Hall Na Yeon Choi [email protected] Vicky Cuming/Jonathan Chafe Greg Morrison IMG 619-200-4933 Maria Fassi Cuming: 011-44-776-851-7081 [email protected] Carlos Rodriguez/Irek Myskow [email protected] Impact Point Chafe: 330-703-3463 In Gee Chun Rodriguez: 760-212-5371 [email protected] Won Park [email protected] BriteFuture Inc Myskow: 305-205-4030 Mina Harigae 386-444-8888 [email protected] Alex Guerrero +82 10 7711 1111 The Society [email protected] Shanshan Feng 280-412-2999 Ruby Chen [email protected] Youngin Chun IMG Taejin Ji +86-18521003681 Nasa Hataoka BRAVO&NEW [email protected] Takumi Zaoya +82-10-6663-9928 206-356-2629 [email protected] Sandra Gal [email protected] Dr. -

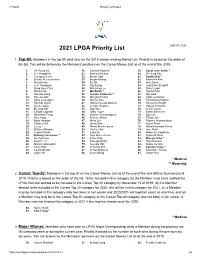

2021 LPGA Priority List JAN-07-2021

1/7/2021 Priority List Report 2021 LPGA Priority List JAN-07-2021 1. Top-80: Members in the top 80 (and ties) on the 2019 season-ending Money List. Priority is based on the order of the list. Ties will be broken by the Members' positions on the Career Money List as of the end of the 2019. 1. Jin Young Ko 30. Caroline Masson 59. Sarah Jane Smith ** 2. Sei Young Kim 31. Azahara Munoz 60. Wei-Ling Hsu 3. Jeongeun Lee6 32. Bronte Law 61. Sandra Gal * 4. Brooke M. Henderson 33. Megan Khang 62. Katherine Kirk 5. Nelly Korda 34. Su Oh 63. Amy Olson 6. Lexi Thompson 35. Ally Ewing 64. Jodi Ewart Shadoff 7. Sung Hyun Park 36. Mi Hyang Lee 65. Stacy Lewis 8. Minjee Lee 37. Mo Martin * 66. Gerina Piller 9. Danielle Kang 38. Suzann Pettersen ** 67. Mel Reid 10. Hyo Joo Kim 39. Morgan Pressel 68. Cydney Clanton 11. Ariya Jutanugarn 40. Marina Alex 69. Pornanong Phatlum 12. Hannah Green 41. Nanna Koerstz Madsen 70. Cheyenne Knight 13. Lizette Salas 42. Jennifer Kupcho 71. Sakura Yokomine 14. Mi Jung Hur 43. Jing Yan 72. In Gee Chun 15. Carlota Ciganda 44. Gaby Lopez 73. Sarah Schmelzel 16. Shanshan Feng 45. Jasmine Suwannapura 74. Xiyu Lin 17. Amy Yang 46. Kristen Gillman 75. Tiffany Joh 18. Nasa Hataoka 47. Mirim Lee 76. Pajaree Anannarukarn 19. Charley Hull 48. Jenny Shin 77. Austin Ernst 20. Yu Liu 49. Nicole Broch Larsen 78. Maria Fernanda Torres 21. Brittany Altomare 50. Chella Choi 79. -

72 Yardage: 6536

Round 2 Starting Times 2016 LPGA and Symetra Tour Qualifying School - Stage II Bobcat Course Friday, October 21, 2016 Purse: $0.00 Par: 36 36 - 72 Yardage: 6536 8:00AM Group 1 Tee 1 8:00AM Group 2 Tee 10 1) Marta Sanz Barrio (Madrid, Spain) 78 +6 1) Gemma Dryburgh (Aberdeen, Scotland) 73 +1 2) Daisy Nielsen (Aalborg, Denmark) 76 +4 2) Daniela Darquea (a) (Quito, Ecuador) 76 +4 3) Kacie Komoto (a) (Honolulu, Hawaii) 79 +7 3) Jessica Welch (Thomasville, Ga.) 72 E 8:11AM Group 3 Tee 1 8:11AM Group 4 Tee 10 1) Christina Foster (Toronto, Ontario) 76 +4 1) Britney Yada (Hilo, Hawaii) 73 +1 2) Lili Alvarez (Durango, Mexico) 79 +7 2) Susy Benavides (Cochabamba, Bolivia) 77 +5 3) Gabriella Then (a) (Rancho Cucamonga, Calif.) 76 +4 3) Csicsi Rozsa (Budapest, Hungary) 74 +2 8:22AM Group 5 Tee 1 8:22AM Group 6 Tee 10 1) Princess Superal (Dasmarinas City, Philippines) 73 +1 1) Maia Schechter (Chapel Hill, N.C.) 68 -4 2) Michelle Koh (Kuantan, Malaysia) 78 +6 2) Hyemin Kim (Seoul, South Korea) 70 -2 3) Lauren Kim (Los Altos, Calif.) 77 +5 3) Manuela Carbajo Re (a) (Nechochea, Argentina) 69 -3 8:33AM Group 7 Tee 1 8:33AM Group 8 Tee 10 1) Fiona Puyo (Epernay, France) 73 +1 1) Christine Wolf (Igls, Austria) 73 +1 2) Mel Reid (Loughborough, England) 70 -2 2) Jenna Peters (Kohler, Wis.) 74 +2 3) Katie Kempter (Albuquerque, N.M.) 73 +1 3) Luciane Lee (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 76 +4 8:44AM Group 9 Tee 1 8:44AM Group 10 Tee 10 1) Rachael Taylor (a) (Bad Griesbach, Germany) 77 +5 1) Megan Osland (Kelowna, B.C.) 72 E 2) Stephanie Na (Port Adelaide, Australia) 78 -

LOTTE Championship Preliminary Entry List

3/3/2020 Competitor Report LOTTE Championship Preliminary Entry List Name Represents Nat. Exempt Rank Top-80 Sei Young Kim Seoul, Republic of Korea KOR 2 Jeongeun Lee6 Gyeonggi-Do, Republic of Korea KOR 3 Brooke M. Henderson Smiths Falls, Ontario CAN 4 Nelly Korda Bradenton, FL USA 5 Lexi Thompson Delray Beach, FL USA 6 Minjee Lee Perth, Australia AUS 8 Danielle Kang Las Vegas, NV USA 9 Hyo Joo Kim Wonju, Republic of Korea KOR 10 Ariya Jutanugarn Bangkok, Thailand THA 11 Hannah Green Perth, Australia AUS 12 Lizette Salas Azusa, CA USA 13 Mi Jung Hur Daejeon, Republic of Korea KOR 14 Yu Liu Beijing, China CHN 20 Brittany Altomare Shrewsbury, MA USA 21 So Yeon Ryu Seoul, Republic of Korea KOR 24 Eun Hee Ji Seoul, Republic of Korea KOR 25 Moriya Jutanugarn Bangkok, Thailand THA 26 Inbee Park Seoul, Republic of Korea KOR 27 Celine Boutier Montrouge, France FRA 28 Caroline Masson Gladbeck, Germany GER 30 Azahara Munoz San Pedro de Alcantara, Spain ESP 31 Su Oh Melbourne, Australia AUS 34 Ally McDonald Fulton, MS USA 35 Mi Hyang Lee Seoul, Republic of Korea KOR 36 Mo Martin Naples, FL USA 37 Marina Alex Wayne, NJ USA 40 Jing Yan Shanghai, China CHN 43 Gaby Lopez Mexico City, Mexico MEX 44 Jasmine Suwannapura Bangkok, Thailand THA 45 Kristen Gillman Austin, TX USA 46 Mirim Lee Gwangju, Republic of Korea KOR 47 Jenny Shin Seoul, Republic of Korea KOR 48 Nicole Broch Larsen Hillerod, Denmark DEN 49 Chella Choi Seoul, Republic of Korea KOR 50 Lydia Ko Auckland, New Zealand NZL 51 Jaye Marie Green Boca Raton, FL USA 52 Annie Park Levittown, NY USA 53 Ashleigh Buhai Johannesburg, South Africa RSA 54 Alena Sharp Hamilton, Ontario CAN 58 https://ocs-lpga.com/pmws/pmws.html?v=6.3.1 1/5 3/3/2020 Competitor Report Name Represents Nat. -

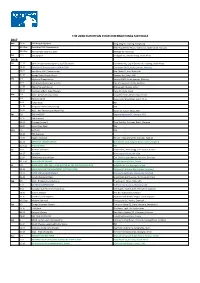

2017 2018 the 2018 European Tour International Schedule

THE 2018 EUROPEAN TOUR INTERNATIONAL SCHEDULE 2017 Nov 23-26 UBS Hong Kong Open Hong Kong GC, Fanling, Hong Kong 30-3 Dec Australian PGA Championship RACV Royal Pines Resort, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia 30-3 Dec AfrAsia Bank Mauritius Open Heritage GC, Mauritius Dec 7-10 Joburg Open Randpark GC, Johannesburg, South Africa 2018 Jan 11-14 BMW SA Open hosted by the City of Ekurhuleni Glendower GC, City of Ekurhuleni, Gauteng, South Africa 12-14 EURASIA CUP presented by DRB-HICOM Glenmarie G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 18-21 Abu Dhabi HSBC Championship Abu Dhabi GC, Abu Dhabi, UAE 25-28 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Emirates GC, Dubai, UAE Feb 1-4 Maybank Championship Saujana G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 8-11 ISPS Handa World Super 6 Perth Lake Karrinyup CC, Perth, Australia 15-18 NBO Oman Golf Classic Almouj Golf, Muscat, Oman 22-25 Commercial Bank Qatar Masters Doha GC, Doha, Qatar Mar 1-4 WGC - Mexico Championship Chapultepec GC, Mexico City, Mexico 1-4 Tshwane Open Pretoria CC, Waterkloof, South Africa 8-11 Indian Open TBA 15-18 Philippines Golf Championship TBA 21-25 WGC - Dell Technologies Match Play Austin CC, Austin, Texas, USA Apr 5-8 THE MASTERS Augusta National GC, Georgia, USA 12-15 TBA (Europe) 19-22 Trophee Hassan II Royal Golf Dar Es Salam, Rabat, Morocco 26-29 Volvo China Open TBA May 5-6 GolfSixes TBA 10-13 TBA (Europe) 17-20 Belgian Knockout Rinkven International GC, Antwerp, Belgium 24-27 BMW PGA CHAMPIONSHIP Wentworth Club, Virginia Water, Surrey, England 31-3 Jun ITALIAN OPEN TBA Jun 7-10 Austrian Golf Open Diamond CC, Atzenbrugg, near Vienna, Austria 14-17 US OPEN Shinnecock Hills GC, NY, USA 21-24 BMW International Open Golf Club Gut Laerchenhof, Pulheim, Germany 28-1 Jul HNA OPEN DE FRANCE Le Golf National, Paris, France Jul 5-8 DUBAI DUTY FREE IRISH OPEN HOSTED BY THE RORY FOUNDATION Ballyliffin GC, Co. -

Success for the Sixes

SUCCESS FOR THE SIXES SEPTEMBER 2017 METHODOLOGY SMS INC. utilised their Sports Radar platform DATE DOMAIN COUNTRY to collect, code and analyse commentary around the Golf Sixes tournament in May at the Centurion Club. www.golfsixes.com Coding the data using the following criteria enabled us to look far beyond the noise AUTHOR/ SENTIMENT TOPICS being generated to understand sentiment AUTHOR TYPE in more detail and the key conclusions; ABOUT SMS INC. SPORTS MARKETING SURVEYS INC. is an commentary in real time. Sports Radar allows SMS experienced and focused sports research INC. to identify and interrogate the sentiment business servicing the sports event, sports & themes of the discussion whilst providing equipment, sport venue, sports federation and structure and meaning to this vast dataset. sports goods industry for over 30 years. Radar is a SaaS-based social and digital intelligence We provide SMART data, analysis and insight platform, efficiently delivering breadth and depth of for leading sports equipment manufacturers, coverage from a wide range of sources including; sports federations, major sports events, speciality retailers, and venue operators to enable • 85,000+ news sources, from over 200 countries our clients to understand more about their • Full Twitter firehose with 30 days of historical data customers, competitors and marketplace. • 2 million+ articles a day • 6,000+ social networks and 5,000+ forums Through Sports Radar, SMS INC. are able to meet the increasing desire in the sports industry • Customer chosen public URLs added as to gain intelligence and insight from online additional data sources www.sportsmarketingsurveysinc.com EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GolfSixes, a new fast-paced golf tournament The event, however, was not without hitches. -

Bragging Rights

Golf 18th hole to secure the victory for Team Europe in 2019, and then retired from golf altogether. U.S. Solheim Cup captain Pat Bragging rights Hurst selected Major champion When Europe meet the U.S., form goes out the window and everything is up for grabs – and five-time Team USA member not least one of the oldest cups in world of sport. This September sees the Solheim Cup Michelle Wie West as an assistant captain to join Angela Stanford in and then the Ryder Cup, with the ladies striking first supporting her this September. Her team will be anchored by 23-year-old Nelly Korda (2021 SOLHEIM CUP appearances. The visitors ran out (DEN), Alice Hewson (ENG), Women’s PGA Championship 31 August – 6 September 18-10 victors in Colorado, with Sophia Popov (GER), Carlota winner and world number one) Inverness Club, Toledo, Ohio 17-year-old Charlie Hull making Ciganda (ESP) and Mel Reid, plus who was a rookie in 2019, The fiercest of transatlantic her debut at Captain’s Pick. the six captain’s picks yet to be her sister Jessica Korda, Lexi rivalries will be renewed on 31st In terms of players, Hull announced. Reid acted assistant Thompson, Danielle Kang and August, with 12 of Europe’s is currently the only Colorado captain to Matthew, who made Brittany Altomare, all of whom finest female golfers defending survivor to be in the 2021 line-up, her bow as captain played at Gleneagles. There are the coveted Waterford Crystal and her 9-3-3 (won-lost-halved) Europe with be without Suzann still places up for grabs in the U.S. -

López Wows with New Record, Marlins Top Braves to Bucks Blowout, Suns’ the Associated Press NL EAST Grounded out on an 0-1 Pitch to Begin the Fourth

www.dailypostathenian.com A14 | DAILY POST-ATHENIAN SPORTS | MONDAY, JULY 12, 2021 ON TV MLB 1 p.m. ........... MLB Draft: Day 2 ...............................................................MLB 8 p.m. .......... Home Run Derby .............................................................ESPN 8 p.m. ......... Home Run Derby (StatCast) ..................................... ESPN2 MEN’S INTERNATIONAL BASKETBALL 8 p.m. .......... Exhibition: Australia vs. U.S., Las Vegas ..................NBCSN AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL 5:30 a.m. .... AFL: North Melbourne at West Coast ............................FS2 MEN’S SOCCER 6:30 p.m. .... CONCACAF Gold Cup: Jamaica vs. Suriname ................FS1 9 p.m. .......... CONCACAF Gold Cup: Costa Rica vs. Guadeloupe ........FS1 LYNNE SLADKY | THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Miami Marlins starting pitcher Pablo Lopez throws during the third inning against the Atlanta Braves on Sunday in Miami. AARON GASH | THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Milwaukee Bucks’ Giannis Antetokounmpo (34) dunks during the second half of Game 3 of the NBA Finals against the Phoenix ‘A lot of emotions’ Suns in Milwaukee. Antetokounmpo’s 41 leads López wows with new record, Marlins top Braves to Bucks blowout, Suns’ The Associated Press NL EAST grounded out on an 0-1 pitch to begin the fourth. Freeman doubled for the MIAMI — Marlins right-hander MARLINS 7, Braves 4 Braves’ first hit, setting up RBI sin- NBA Finals lead now 2-1 Pablo López set a major league record gles by Albies and Arcia. by striking out the first nine batters 1986 and matched by Jacob deGrom López gave up three runs in six BY BRIAN MAHONEY NBA FINALS to start a game, pitching Miami past in 2014 and German Marquez in 2018. innings — after his sensational start, AP Basketball Writer the Atlanta Braves 7-4 Sunday. -

UCOM Übernimmt Porsche European Open

U.COM Event übernimmt Porsche European Open • Dreijahresvertrag zwischen U.COM Event, der European Tour und Titelsponsor Porsche • Bekenntnis zu hochklassigem Golfsport in Deutschland • „Eine Herzensangelegenheit“, sagt U.COM Geschäftsführer Dirk Glittenberg. 02. Dezember 2020 – Es ist ein eindrucksvolles Zeichen für Spitzengolf in besonderen Zeiten: U.COM Event ist neuer Veranstalter der prestigeträchtigen Porsche European Open. Ein Dreijahresvertrag mit der European Tour und Titelsponsor Porsche garantiert die Fortführung eines der traditionsreichsten Turniere im europäischen Profigolf bis 2023 und ist gleichzeitig ein Bekenntnis zu hochklassigem Golfsport in Deutschland. Vom 3. bis zum 6. Juni 2021 werden die Top-Golfer bei der dann sechsten Austragung der Porsche European Open zum vierten Mal auf dem anspruchsvollen Porsche Nord Course der Green Eagle Golf Courses vor den Toren Hamburgs abschlagen. Das Preisgeld beträgt 1,2 Millionen Euro. Titelverteidiger Paul Casey, dreimaliger Ryder-Cup-Champion und frühere Nummer drei der Welt, hat seine Teilnahme bereits zugesagt. „Die Übernahme der Porsche European Open ist für uns eine Herzensangelegenheit“, sagt Dirk Glittenberg, Geschäftsführer der U.COM Event. „Wir leben und lieben den Golfsport und wollen helfen, ihn in Deutschland weiterzuentwickeln und gleichzeitig neue Eventerlebnisse schaffen, die über den Wettbewerb hinausreichen. Gemeinsam mit unseren Partnern möchten wir auf der tollen Anlage von Green Eagle Golf Courses bestehende und neue Golf- und Event-Fans begeistern und dabei diesen wunderbaren Sport zugänglich und vor allem unterhaltsam präsentieren.“ Wertvolle Erfahrung als Veranstalter und Promoter U.COM Media und die Porsche AG arbeiten seit Jahren bereits erfolgreich beim Porsche Tennis Grand Prix zusammen. Von dieser gemeinsamen Erfahrung sollen die Porsche European Open ebenso profitieren wie von der langen Geschichte der U.COM Event als internationalem Turnierveranstalter. -

MEIJER LPGA CLASSIC Professionals 1St

Pairings - Round 1 MEIJER LPGA CLASSIC Camera-Ready Copy Page 1 of 4 _PS-R1-8PT-Narrow Time CME Group Professionals 1st Tee Rank PERRINE DELACOUR, Laon, France 87 7:15 BIANCA PAGDANGANAN, Philippines 134 1 BRIANNA DO, Lakewood, CA 130 KLARA SPILKOVA, Prague, Czech Republic 110 7:26 MIN SEO KWAK, Seoul, Republic of Korea 133 3 SU OH, Melbourne, Australia 98 AYAKO UEHARA, Naha, Japan 83 7:37 ESTHER HENSELEIT, Hamburg, Germany 94 5 JENNIFER SONG, Orlando, FL 100 CHARLEY HULL, Woburn, England 53 7:48 GABRIELA RUFFELS *, Melbourne, Australia 7 JODI EWART SHADOFF, North Yorkshire, ENG 75 LYDIA KO, Auckland, New Zealand 1 7:59 JIN YOUNG KO, Seoul, Republic of Korea 14 9 MEL REID, Derby, England 39 STACY LEWIS, The Woodlands, TX 41 8:10 JESSICA KORDA, Jupiter, FL 5 11 LEONA MAGUIRE, Cavan, Ireland 20 ALLY EWING, Fulton, MS 13 8:21 JENNIFER KUPCHO, Westminster, CO 27 13 MADELENE SAGSTROM, Enkoping, Sweden 61 NASA HATAOKA, Ibaraki, Japan 29 8:32 JENNY COLEMAN, Rolling Hills Estates, CA 31 15 MIN LEE, Taoyuan City, Chinese Taipei 42 DANA FINKELSTEIN, Chandler, AZ 97 8:43 HALEY MOORE, Escondido, CA 131 17 GERINA PILLER, Roswell, NM 63 KELLY TAN, Batu Pahat, Malaysia 116 8:54 RUIXIN LIU, Guangdong, China 118 19 LINNEA STROM, Hovas, Sweden 125 LOUISE RIDDERSTROM, Stocksund, Sweden 147 9:05 JACLYN LEE, Calgary, Alberta 158 21 JANIE JACKSON, Huntsville, AL 141 SAMANTHA TROYANOVICH #, Grosse Pnt, MI 9:16 CAROLINE INGLIS, Eugene, OR 136 23 EMMA TALLEY, Princeton, KY 142 Pairings - Round 1 MEIJER LPGA CLASSIC Camera-Ready Copy Page 2 of 4 _PS-R1-8PT-Narrow -

SECKFORD P Age�2 POIN TS4G OLF New� Sc GOLF�CLUB Heme SSPPRRIINNGG��SSPPEECCIIAALL

SU21yeFarsold FOLK MARCH/APRIL2020 & 1999-2020 NORFOGLOLKFE R see SECKFORD p age2 POIN TS 4G OLF new sc GOLFCLUB heme SSPPRRIINNGGSSPPEECCIIAALL 18HolesofGolf Par4EnglishBreakfast (beforeplay) ££2255 PPPP +Free25RangeToken Everydayfrom11am CCaallll0011339944338888000000ttoobbooookk Charitygolfeventat Points 4Golf SuffolkGolfCourse UffordPark AshleyPickeringPhotography Adonation ‘FlexibleGolftosuityourlifestyle’ Woodbridgeis fromeach settohosta player's MayBank entryfee Intoday’sfastmovingsocietymanygolferscan’tjustifygolfclubentrancefeesandannualmembership Holidaymeeting willbe feesbecausetheysimplydon’thavethechancetoplayenoughgolf! toraisefundsfor collected Points 4GolfMembership isatriedandtestedschemethatallowsgolfersatotallyflexibleandlowcost theSuffolk tosupport approachtomembership.WhenyoujoinSeckfordGolfClubasa P4G memberyoubuyanumberof Punchhorse. charities forthe pointswhichareheldonamembershipaccount.Thepoint’soptionsareavailableinvaryingsizesbased Theevent, benefitof onaslidingscaleensuringthemorepointsyoupurchasethebetterthevaluebecomes.Eachtimea foundedbythe allownersand memberplaysanumberofpoints,dependingonwhentheyplay,aredeductedfromtheaccount.Points complexowner breedersofthis canalsobeusedforguests,buggiesandtrolleys. andkeengolfer rareandiconic ColinAldous, Whenyoujoin,thatfirstpurchasemeansyourpointsarevaliduntiltheendofthefollowingyear,eg.join Suffolkhorse. anytimein2020andyouneedtotopupby31stDecember2021. P4G memberscan‘TopUp’with (inset),issetto additionalpointsatanytimethroughouttheyearasrequired. attractgolfers