Complaint Affidavit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conspiracy of Fools”

Submitted version of review published in GARP Risk Review Review of “Conspiracy of Fools” Joe Pimbley Kurt Eichenwald’s Conspiracy of Fools (Broadway Books, 2005) is a spellbinding account of the rise and fall of Enron. In nearly 700 pages the reader finds answers to “what happened?” and “how did it happen?” Based on retrospective interviews with more than a hundred primary and secondary actors in this drama, the author creates multiple, parallel story lines. He jumps back and forth between these sub-plots in a manner that maintains energy and gives the reader many natural stopping points. The great strengths of Conspiracy are that it’s thorough, extremely well- written, captivating, and, finally, it rings true. The author avoids the easy, simple conclusions that all the executives are “guilty” of crimes or plain greed and that the media-lionized whistle-blower is pure of heart. We see the ultimate outcome as personal tragedies for Jeff Skilling (President) and Ken Lay (CEO) even though they are undeniably culpable. Culpability and guilt are not synonymous, however, and different readers will have widely different judgments to render on these two men. The view of Andrew Fastow is not so murky. He and a handful of his associates did indeed lie, cheat, and steal for personal gain. Fastow’s principle “contribution” to Enron was the creation of structured finance transactions to skirt accounting rules. This one-sentence description doesn’t tell the reader much. Eichenwald gives many examples to flesh out the concept. The story of “Alpine Investors” provides the simplest case. The company wished to sell the Zond Corporation, a wind-farm operator, prior to the closing of Enron’s purchase of Portland General. -

Enron (Student Editions) Online

jJGyX [Download] Enron (Student Editions) Online [jJGyX.ebook] Enron (Student Editions) Pdf Free Lucy Prebble ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #5327046 in Books Bloomsbury Academic 2016-01-28 2016-01-28Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 197.10 x 11.18 x 5.22l, .33 #File Name: 1472508742176 pagesBloomsbury Academic | File size: 71.Mb Lucy Prebble : Enron (Student Editions) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Enron (Student Editions): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Piece of crapBy John StricklettExposes the playwright's laughable understanding of business and economics. Childish and naive. Little substance.Though it has some value with regards to its artistic and relatively accurate portrayal of its characters.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. ENRON, NEVER AGAINBy Alfonso DavilaEverybody should read and watch this video!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. For schoolBy CaseyThis book is strange but it isn't a bad read. It is a pretty short/ quick read but worth this price. The only difference between me and the people judging me is they weren't smart enough to do what we did.One of the most infamous scandals in financial history becomes a theatrical epic. At once a case study and an allegory, the play charts the notorious rise and fall of Enron and its founding partners Ken Lay and Jeffrey Skilling, who became 'the most vilified figure from the financial scandal of the century.'This -

Understanding LJM

McCullough Research 6123 S.E. Reed College Place Portland, Oregon 97202 Voice: 503-771-5090 Fax: 503-771-7695 Internet: [email protected] Memorandum Date: February 7, 2002 To: McCullough Research Clients From: Robert McCullough Subject: Understanding LJM Overview Near the end of 1999, Enron established a very thin “unaffiliated” entity named “LJM” managed by Andrew Fastow, Enron’s Chief Financial Officer, that was designed to allow a series of off-balance sheet transactions with Enron. The Powers Report has identified this and its follow-on Special Purpose Entities (SPEs) as a critical issue in corporate governance and argues persuasively that they had little economic merit. The report also questions whether they should ever had been unconsolidated.1 A careful review clearly indicates that while their consistency with Enron’s governance may have been in question, they were part of Enron’s overall financial strategy and were used to finance other major groups of SPEs including Osprey and Whitewing. Logically, these additional SPEs should also have been consolidated in 3rd Quarter of 2001 along with Swap Sub and Chewco. The feverish ingenuity of the LJM subsidiaries and partnerships seems to reflect a race between Andrew Fastow and Arthur Andersen. There is a strong impression that Enron’s Chief Financial Officer was trying to invent solutions to traditional accounting prohibitions faster than his auditors 1Consolidated means added together for financial reporting purposes. Unconsolidated entities would not show up in the balance sheet -

Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip Into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization

Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization A special report by Public Citizen’s Critical Mass Energy and Environment Program Washington, D.C. March 2002 Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization A special report by Public Citizen’s Critical Mass Energy and Environment Program Washington, D.C. March 2002 This document can be viewed or downloaded at www.citizen.org/cmep. Public Citizen 215 Pennsylvania Ave., S.E. Washington, D.C. 20003 202-546-4996 fax: 202-547-7392 [email protected] www.citizen.org/cmep © 2002 Public Citizen. All rights reserved. Public Citizen, founded by Ralph Nader in 1971, is a non-profit research, lobbying and litigation organization based in Washington, D.C. Public Citizen advocates for consumer protection and for government and corporate accountability, and is supported by over 150,000 members throughout the United States. Liquid Assets: Enron's Dip into Water Business Highlights Pitfalls of Privatization Executive Summary The story of Enron Corp.’s failed venture into the water business serves as a cautionary tale for consumers and policymakers about the dangers of turning publicly operated water systems and resources over to private corporations and creating a private “market” system in which water can be traded as a commodity, as Enron did with electricity and tried to do with water. Enron’s water investments, which contributed to the company’s spectacular collapse, would not have been permitted had the Public Utility Holding Company Act (PUHCA) been properly enforced and not continually weakened by the deregulation initiatives advocated by Enron and other energy companies. -

Ebook Download Enron the Rise and Fall 1St Edition Ebook

ENRON THE RISE AND FALL 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Loren Fox | 9780471478881 | | | | | Enron The Rise and Fall 1st edition PDF Book It was very informative and if I was interested I would be more inclined to finish it. The story of Enron is one that will reverberate in global financial and energy markets as well as in criminal and civil courts for years to come. It was reported at the time that Moody's and Fitch , two of the three biggest credit-rating agencies, had slated Enron for review for possible downgrade. November 15, At the beginning of , the Enron Corporation, the world's dominant energy trader, appeared unstoppable. Event occurs at Konzelmann September By using the site, you consent to the placement of these cookies. Other editions. Of the three books [including Pipe Dreams and Anatomy of Greed ], this one offers the most detailed explanation of Enron as a business. While it breaks no new ground, the tool kit provides, in one place, an overview of the accounting and auditing literature, SEC requirements and best practice guidance concerning related party transactions. Archived from the original on March 22, Indergaard Rutgers University Press, Please, though, remember this: Never take customer and employee confidence for granted. I found an organization that, in the spirit of the last decade, over-reached; Chairman Kenneth Lay, Jeffrey Skilling, and company believed they could transform a pipeline operator into a virtual corporation that traded a dizzying. This is a dummy description. In addition, the company admitted to repeatedly using "related-party transactions," which some feared could be too-easily used to transfer losses that might otherwise appear on Enron's own balance sheet. -

Enron Special Investigations Report

® William Powers, Jr. Member of the Enron Board of Directors and Chairman of the Special Investigation Committee 3600 Murillo Circle Austin, TX 78703 512-232-1120 February 1,2002 To the Members of the Board of Directors Enron Corporation Enclosed is a copy of the Report of the Special Investigation Committee. William Powers, Jr. Enclosure REPORT OF INVESTIGATION BY THE SPECIAL INVESTIGATIVE COMMITTEE OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF ENRON CORP. William C. Powers, Jr., Chair Raymond S. Troubh Herbert S. Winokur, Jr. Counsel Wilmer, Cutler & Picketing February 1, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ...................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................... i.................................................................................. 29 I. BACKGROUND: ENRON AND SPECIAL PURPOSE ENTITIES ............................. 36 II. CHEWCO ...: ..................................................................................................................... 41 A. Formation of Chewco ........................................................................................... 43 B. Limited Board Approval ....................................................................................... 46 C. SPE Non-Consolidation "Control" Requirement .................................................. 47 D. SPE Non-Consolidation "Equity" Requirement ................................................... 49 E. Fees Paid to Chewco/Kopper ............................................................................... -

Enron and the Regulatory Cycle

ENRON AND THE REGULATORY CYCLE Tara Naib1 Duke University Durham, NC April, 2002 1 Tara Naib graduated Summa Cum Laude from Duke in May 2002 with a BS in Economics. She was also awarded High Distinction for her thesis. Acknowledgement I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Stephen Wallenstein, for his advice, criticisms, and contribution to this paper. I would also like to thank Professor Connel Fullenkamp for his patience and insight during our many long discussions and revisions, but most of all for his friendship. This thesis is dedicated to my father. 2 Abstract This paper attempts to tie Enron’s rise, decline and ultimate fall to an economic theory known as the regulatory cycle. The regulatory cycle can be divided into three categories: crisis, regulatory response, and innovation, and will serve as a framework to discuss Enron’s insight and mistakes. The emphasis of this essay is on innovation and regulatory response. Enron’s innovative ideas that were responsible for its success are reviewed in some detail in the innovation section. Also in this section is a discussion of Enron’s questionable activities through the use of Special Purpose Vehicles. The regulatory response section addresses some of the ideas for reform in the wake of the Enron crisis once the framework for effective regulatory response has been established. 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction p. 5 II. The Regulatory Cycle p. 6 III. Enron as Part of a Regulatory Cycle p. 8 IV. Enron: Financial Innovation, Both Good and Bad p. 9 A. Financial Innovation from the Beginning: Enron’s Birth and Early Years p. -

Enron Scandal: the Fall of a Wall Street Darling

Enron Scandal: The Fall of a Wall Street Darling The story of Enron Corp. is the story of a company that reached dramatic heights, only to face a dizzying fall. Its collapse affected thousands of employees and shook Wall Street to its core. At Enron's peak, its shares were worth $90.75; when it declared bankruptcy on December 2, 2001, they were trading at $0.26. To this day, many wonder how such a powerful business, at the time one of the largest companies in the U.S, disintegrated almost overnight and how it managed to fool the regulators with fake holdings and off-the-books accounting for so long. Enron's Energy Origins Enron was formed in 1985, following a merger between Houston Natural Gas Co. and Omaha-based InterNorth Inc. Following the merger, Kenneth Lay, who had been the chief executive officer (CEO) of Houston Natural Gas, became Enron's CEO and chairman and quickly rebranded Enron into an energy trader and supplier. Deregulation of the energy markets allowed companies to place bets on future prices, and Enron was poised to take advantage. In 1990, Lay created the Enron Finance Corp. To head it, he appointed Jeffrey Skilling, whose work as a McKinsey & Co consultant had impressed Lay. Skilling was at the time one of the youngest partners at McKinsey. Why Enron Collapsed Skilling joined Enron at an auspicious time. The era's regulatory environment allowed Enron to flourish. At the end of the 1990s, the dot-com bubble was in full swing, and the Nasdaq hit 5,000. -

Enron Should Not Have Been a Surprise and the Next Major Fraud Should Not Be Either

Enron Should Not Have Been a Surprise and the Next Major Fraud Should Not Be Either Jerry B. Hays Austin Community College Donald L. Ariail Southern Polytechnic State University The CFO of an Enron Special Purpose Entity (SPE) discusses unheeded warnings and dismissed red flags prior to the Enron accounting scandal. He provides these experiences from the perspective of 30 years as a CPA and CIA and as the former Vice President of Business and Finance of a multibillion dollar domestic division of a major oil company. Next an update is provided of the status of white collar crime; and, a discussion follows regarding the lessons learned from Enron and the prospects for future fraud. INTRODUCTION The name Enron is now infamous. The Enron fraud was not only one of the largest of many accounting scandals in the late 1900s and early 2000s; it was also the scandal that directly led to the demise of the international accounting firm of Arthur Andersen. While much has been written about this fraud, little information has previously been provided by partners of the many Special Purpose Entities (SPE) used by Enron to perpetuate the fraud. By providing a first person perspective by the CFO of one of the SPEs, this paper seeks to partially fill this gap. Following the CFO’s input, a review of several white collar fraud surveys provides an update post Enron of the status of accounting fraud; and, in the final section, lessons learned from Enron and prospects for the future of accounting fraud are discussed. PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE OF AN SPE’S CFO In June of 2000, I (the lead author), along with four partners, signed an oil and gas exploration and development agreement with Enron. -

In Re Enron Corporation Securities Litigation 01-CV-3624-Plaintiffs

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION In re ENRON CORPORATION SECURITIES § Civil Action No. H-01-3624 LITIGATION § (Consolidated) § § CLASS ACTION This Document Relates To: § § MARK NEWBY, et al., Individually and On § Behalf of All Others Similarly Situated, § § Plaintiffs, § § vs. § § ENRON CORP., et al., § § Defendants. § § THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF § CALIFORNIA, et al., Individually and On § Behalf of All Others Similarly Situated, § § Plaintiffs, § § vs. § § KENNETH L. LAY, et al., § § Defendants. § § PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION TO MOTION TO DISMISS FILED BY VINSON & ELKINS L.L.P. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Introduction and Factual Overview ............................ 1 A. The Year-end 97 Crisis - Formation of Chewco................. 4 B. The 97-00 Successes – Enron's Stock Soars................... 7 C. The LJM Partnerships and SPEs......................... 9 D. Dark Fiber Swaps.................................18 E. Hidden/Disguised Loans.............................19 F. Enron's Corporate Culture............................19 G. Enron's Access to the Capital Markets......................21 H. Enron's False and Misleading SEC Filings ....................22 I. Late 00/Early 01 Prop-Up............................26 J. The Impending Collapse and Attempted Coverup................26 K. The End of Enron.................................30 L. Exposure of Vinson & Elkins' Complicity in the Fraud.............31 II. The CC Properly Alleges Primary Liability of Vinson & Elkins Under §10(b) and Rule 10b-5 -

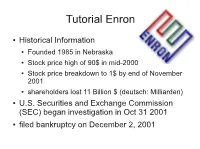

Tutorial Enron

Tutorial Enron ● Historical Information ● Founded 1985 in Nebraska ● Stock price high of 90$ in mid-2000 ● Stock price breakdown to 1$ by end of November 2001 ● shareholders lost 11 Billion $ (deutsch: Milliarden) ● U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began investigation in Oct 31 2001 ● filed bankruptcy on December 2, 2001 Enron's success ● Thrive of Enron ● selling of electricity and gas ● through strong lobying by Enron a deregulation of prices was prevented ● Dec. 2000, market capitalization exceeded $60 billion, – 70 times earnings http://www.50statesclassifieds.com/uploadedi mages/4703312gas1.jpg – six times book value – an indication of the stock market’s high expectations about its future Management board ● CEOs ● Kenneth Lay, Founder, former Chairman and CEO (CEO 1985-2002) ● Jeffrey Skilling, former President, CEO (Dez. 2000- Aug 2001) and COO ● Rebecca Mark-Jusbasche, former Vice Chairman, Chairman and CEO of Enron International ● Stephen F. Cooper, Interim CEO and CRO ● Andrew Fastow, former CFO ● Auditing company ● Arthur Anderson (Auditing company) Time-Line ● 01.11.2000 Lay begins selling shares ● 12.02.2001 Skilling is named CEO ● 21.06.2001 Skilling is hit in the face with a pie ● 14.08.2001 Skilling resigns ● 16.08.2001 Lay discusses Skilling's departure ● 21.08.2001 Lay states that increasing stock price has one of the highest priority ● 16.09.2001 Lay to employees: “the third quarter is looking great” ● www.fact-index.com/t/ti/timeline_of_the_enron_scandal.html Outrages (Excerpt) ● Kenneth Lay ● Spread of -

Enron Case Study

Fraud and Deception: An Enron Case Study By National Tax Institute, Inc. 2 Fraud and Deception: An Enron Case Study The author is not engaged by this text or any accompanying lecture or electronic media in the rendering of legal, tax, accounting, or similar professional services. While the legal, tax, and accounting issues discussed in this material have been reviewed with sources believed to be reliable, concepts discussed can be affected by changes in the law or in the interpretation of such laws since this text was printed. For that reason, the accuracy and completeness of this information and the author's opinions based thereon cannot be guaranteed. In addition, state or local tax laws and procedural rules may have a material impact on the general discussion. As a result, the strategies suggested may not be suitable for every individual. Before taking any action, all references and citations should be checked and updated accordingly. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert advice is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. —-From a Declaration of Principles jointly adopted by a committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations. Copyright 2010 All rights reserved. Copies of this document may not be made without expressed written permission from the author. National Tax Institute, Inc. Fraud and Deception: An Enron Case Study 3 Fraud and Deception: An Enron Case Study 4 Fraud and Deception: An Enron Case Study Objectives: The purpose of this course is to review the factors that led to the demise of Enron.