Appalachian Trail - North District Shenandoah National Park Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Plates Soups Beverages Skyland Favorites

Welcome to the Pollock Dining Room! We hope that you enjoy your dining experience during your visit to Skyland. Should you need LUNCH any assistance with food descriptions, allergies or dietary concerns, please contact any of our restaurant supervisors, managers or chefs. Thank SMALL PLATES you for dining with us, and enjoy your meal! PIMENTO CHEESE FONDUE 804 cal $10 Housemade Pimento Cheese, Bacon Marmalade, Pita Chips MARYLAND CRABCAKE 596 cal $14 Lump Crab, Roasted Corn Salsa, Lemon Dill Aoili SALAMI CHEESE BOARD 718 cal $18 Assorted Cheeses, Calbrese Salami, Crackers FIRECRACKER POPCORN 557 cal $10 SHRIMP Panko Breaded, Sweet Chili Sriracha Glaze, Wasabi Slaw SKYLAND FAVORITES SWEET POTATO POUTINE 475 cal $10 Sweet Potato Fries, Pulled BBQ BASKET FRIED CHICKEN 914 cal $20 Pork, Veal Demi Glace, Crumbled Crispy Fried, Yukon Mashed, Cranberry Relish Goat Cheese, Crispy Sage FISH AND CHIPS 614 cal $14 HUMMUS PLATTER 706 cal $9 Beer Battered Haddock, French Fries, Roasted Red Pepper Coleslaw, Old Bay Tarter Hummus, Sliced Cucumbers, Cherry Tomatoes, Kalamata PULLED PORK TACO 1476 cal $14 Olives, Pita Chips Slow Cooked Pulled Pork, Roasted Corn Relish, BBQ Sauce, Flour Tortillas SOUPS POLLOCK TURKEY POT PIE 752 cal $14 CHARLESTON SHE CRAB CHEF’S SEASONAL SOUP Celery, Carrots, Onions, Potatoes. A flaky crust. House Salad. Sherry Scented Made Fresh Daily Cream, Lump Crab Cup $4 Cup 307cal $6 Bowl $6 Bowl 409 cal $8 BEVERAGES We believe in using locally grown organic, Fair Trade Rainforest Bold Coffee® $2.75 sustainable harvested products whenever possible as part of our commitment to protect (Regular or Decaf) our environments and cherish our natural Espresso, Latte, Cappuccino $4.00 surroundings. -

Field Trips Guide Book for Photographers Revised 2008 a Publication of the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs

Field Trips Guide Book for Photographers Revised 2008 A publication of the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs Copyright 2008. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced or copied in any manner whatsoever. 1 Preface This field trips guide book has been written by Dave Carter and Ed Funk of the Northern Virginia Photographic Society, NVPS. Both are experienced and successful field trip organizers. Joseph Miller, NVPS, coordinated the printing and production of this guide book. In our view, field trips can provide an excellent opportunity for camera club members to find new subject matter to photograph, and perhaps even more important, to share with others the love of making pictures. Photography, after all, should be enjoyable. The pleasant experience of an outing together with other photographers in a picturesque setting can be stimulating as well as educational. It is difficullt to consistently arrange successful field trips, particularly if the club's membership is small. We hope this guide book will allow camera club members to become more active and involved in field trip activities. There are four camera clubs that make up the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs McLean, Manassas-Warrenton, Northern Virginia and Vienna. All of these clubs are located within 45 minutes or less from each other. It is hoped that each club will be receptive to working together to plan and conduct field trip activities. There is an enormous amount of work to properly arrange and organize many field trips, and we encourage the field trips coordinator at each club to maintain close contact with the coordinators at the other clubs in the Alliance and to invite members of other clubs to join in the field trip. -

Backpacking: Bird Knob

1 © 1999 Troy R. Hayes. All rights reserved. Preface As a new Scoutmaster, I wanted to take my troop on different kinds of adventure. But each trip took a tremendous amount of preparation to discover what the possibilities were, to investigate them, to pick one, and finally make the detailed arrangements. In some cases I even made a reconnaissance trip in advance in order to make sure the trip worked. The Pathfinder is an attempt to make this process easier. A vigorous outdoor program is a key element in Boy Scouting. The trips described in these pages range from those achievable by eleven year olds to those intended for fourteen and up (high adventure). And remember what the Irish say: The weather determines not whether you go, but what clothing you should wear. My Scouts have camped in ice, snow, rain, and heat. The most memorable trips were the ones with "bad" weather. That's when character building best occurs. Troy Hayes Warrenton, VA [Preface revised 3-10-2011] 2 Contents Backpacking Bird Knob................................................................... 5 Bull Run - Occoquan Trail.......................................... 7 Corbin/Nicholson Hollow............................................ 9 Dolly Sods (2 day trip)............................................... 11 Dolly Sods (3 day trip)............................................... 13 Otter Creek Wilderness............................................. 15 Saint Mary's Trail ................................................ ..... 17 Sherando Lake ....................................................... -

Horse Use and Pack Animal Rules and Regulations in Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2/2018 Horse Use and Pack Animals Overview Numerous trails in Shenandoah National Park burros, and llamas are all designated as “pack are designed for horseback riding and the use animals.” Collectively, we refer to them as horses of pack animals. Legally defined, horses, mules, in this guide. Horse Trails To minimize trail use problems with hikers, traffic only and are not maintained for horses. riders may take horses only into areas designated Meadows and native grasslands, including Big for their use. Horse trails are marked with yellow Meadows, contain sensitive vegetation and are paint blazes on trees. Most of the Park’s fire strictly off-limits to horse use. The paved roads roads are included in the horse trail system and and developed areas in the Park (such as lodging are blazed accordingly. Commercial horse use areas and campgrounds) have high vehicle traffic services, such as guided trail rides, require a and other visitor use and are not suited for Commercial Use Authorization. horses. Use of horses in these areas is prohibited. Exceptions include short stretches of travel The Appalachian Trail (white-blazed) and along paved roads to access horse use trailheads other hiking trails (blue-blazed) are for foot close to one another. Trails Open North District: Central District: StonyMan Mountain Horse Trail to Park Animal Use Beecher Ridge Trail† Berry Hollow Fire Roadº Stony Mountain Trailº Bluff Trail Conway River Fire Road Tanners Ridge Horse Trailº Browntown Trail -

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Piney River, Shenandoah National Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 1999 Revised 2006 Piney River Shenandoah National Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Piney River Shenandoah National Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Cultural Landscapes Inventory – General Information The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI) is a database containing information on the historically significant landscapes within the National Park System. This evaluated inventory identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved inventory records when all required data fields are entered, the park superintendent concurs with the information, and the landscape is determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places through a consultation process or is otherwise managed as a cultural resource through a public planning process. The CLI, like the List of Classified Structures (LCS), assists the National Park Service (NPS) in its efforts to fulfill the identification and management requirements associated with Section 110(a) of the National Historic Preservation Act, National Park Service Management Policies (2001), and Director’s Order #28: Cultural Resource Management. Since launching the CLI nationwide, the NPS, in response to the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), is required to report information that respond to NPS strategic plan accomplishments. Two goals are associated with the CLI: 1) increasing the number of certified cultural landscapes (1b2B); and 2) bringing certified cultural landscapes into good condition (1a7). -

Nomination Form

VLR Listed: 12/4/1996 NRHP Listed: 4/28/1997 NFS Form 10-900 ! MAR * * I99T 0MB( No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) .^^oTT^Q CES United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Skyline Drive Historic District other name/site number: N/A 2. Location street & number: Shenandoah National Park (SHEN) not for publication: __ city/town: Luray vicinity: x state: VA county: Albemarle code: VA003 zip code: 22835 Augusta VA015 Greene VA079 Madison VA113 Page VA139 Rappahannock VA157 Rockingham VA165 Warren VA187 3. Classification Ownership of Property: public-Federal Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 9 8 buildings 8 3 sites 136 67 structures 22 1 objects 175 79 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: none Name of related multiple property listing: Historic Park Landscapes in National and State Parks 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x _ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x _ meets __^ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant x nationally __ statewide __ locally. ( __ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) _____________ Signature of certifying of ficial Date _____ ly/,a,-K OAJ. -

8. Terrain and the Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862

2. Mesoproterozoic Geology of the Blue Ridge Province in North-Central Virginia: Petrologic and Structural Perspectives on Grenvillian Orogenesis and Paleozoic Tectonic Processes By Richard P. Tollo,1 Christopher M. Bailey,2 Elizabeth A. Borduas,1 and John N. Aleinikoff3 Introduction over the region, produced up to 770 mm (30.3 in) of rain in the vicinity of Graves Mills (near Stops 18 and 19) in northwestern This field trip examines the geology of Grenvillian base- Madison County. During this storm, more than 1,000 shallow ment rocks located within the core of the Blue Ridge anticlin- rock, debris, and soil slides mobilized into debris flows that orium in north-central Virginia over a distance of 64 kilometers were concentrated in northwestern Madison County (Morgan (km) (40 miles (mi)), from near Front Royal at the northern and others, 1999). The debris flows removed large volumes of end of Shenandoah National Park southward to the vicinity of timber, soil, and rock debris, resulting in locally widened chan- Madison. This guide presents results of detailed field mapping, nels in which relatively unweathered bedrock commonly was structural analysis, petrologic and geochemical studies, and iso- exposed. Stops 18 and 19 are located within such channels, and topic investigations of Mesoproterozoic rocks directed toward are typical of the locally very large and unusually fresh expo- developing an understanding of the geologic processes sures produced by the event. Materials transported by debris involved in Grenvillian and Paleozoic orogenesis in the central flows were typically deposited at constrictions in the valley Appalachians. Stops included in this field guide illustrate the pathways or on top of prehistoric fans located at the base of lithologic and structural complexity of rocks constituting local many of the valleys that provided passageways for the flows. -

Appalachian Northern Flying Squirrels and High Elevation Spruce-Fir Ecosystems: an Annotated Bibliography

Appalachian northern flying squirrels and high elevation spruce-fir ecosystems: An annotated bibliography Corinne A. Diggins1 and W. Mark Ford2 1 Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 100 Cheatham Hall, Blacksburg, VA, 24061 2U.S. Geological Survey, Virginia Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, 106 Cheatham Hall, Blacksburg, VA, 24061 Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel at Whitetop Mountain, VA (Photo Credit: C.A. Diggins) North American boreal forest communities exist at the southernmost extent of their range in the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States. On high-elevation peaks and ridges in the central and southern Appalachian Mount- ains, this forest type represents a unique assemblage of boreal (northern) and austral (southern) latitude species following the end of the Pleistocene glaciation. Although south of the actual glaciated area, as the glaciers retreated and the climate warmed, boreal forests retreated northward and to cooler, high- elevation sites in the App- Figure 1. Distribution of red spruce-fir forests in the central and alachians. In the southern southern Appalachian Mountains. Most Virginia sites are Appalachians, these boreal forest represented by dots, indicating the presence of a red spruce communities are dominated by stand, not indicative of the limited area. red spruce (Picea rubens)-Fraser fir (Abies fraseri) in southwestern Virginia, western North Carolina, and eastern Tennessee occurring above elevations of 4500 feet (Figure 1). In the central Appalachians, red spruce forests along with some small stands of balsam fir (A. balsamea) occur in eastern West Virginia and northwestern Virginia above elevations of 3000 feet (Figure 1). -

A New Long-Tailed Weasel County Record in Shenandoah National Park

Virginia Journal of Science Volume 67, Issue 1 & 2 Spring/Summer 2016 doi: 10.25778/QY29-TQ49 A New Long-tailed Weasel County Record in Shenandoah National Park Jason V. Lombardi1, Michael T. Mengak1*, Steven B. Castleberry1, V. K. Terrell1, and Mike Fies2 1Daniel B. Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602. 2Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Verona, VA 24482 *Corresponding Author - Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Though abundant throughout much of its range, the ecology and local geographic distribution of Mustela frenata (Long-tailed Weasel) is not well- known, especially in the central Appalachian Mountains. In 2015, we conducted a camera study in rock outcrop habitats within Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. Our objective was to determine the presence of mammals considered uncommon in these habitats. After 2,016 trap nights, we report eleven photographic captures of Long-tailed Weasels at eight sites. Two of these sites represent the first record of this species in Rappahannock County, Virginia. These detections represent the first record of Long-tailed Weasels in Shenandoah National Park in 60 years and extend their known range within the Park. Mustela frenata Lichtenstein (Long-tailed Weasel), is abundant throughout most of its geographic range, which extends from southern Canada to northwestern South America (Chapman 2007). Long-tailed Weasels are considered habitat generalists, as they have been found in low-elevation agriculture areas to high-elevation (2,133 m) forests of Colorado (Chapman 2007, Quick 1949). However, their ecology and geographic distribution throughout the eastern United States as compared to other furbearer species is essentially unknown (Richter and Schauber 2006). -

Climbing Guidelines in Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2/2018 Climbing Guidelines Overview People are drawn to Shenandoah National Park Rock climbing is a unique experience that for many different reasons; some want to take creates a special bond between the climber and in the beautiful scenery along Skyline Drive, the rock face. To have a great experience and others want to enjoy nature and the feelings of ensure that those after you do as well, follow solitude and renewal that wilderness brings. the guidelines and recommendations below. Why Guidelines? The Shenandoah Climbing Management These guidelines will allow us to: Guidelines have been developed to protect • Manage recreational use. Shenandoah’s natural resources, while also • Protect natural resources. providing visitors opportunities for rock • Provide climbing opportunities in the Park. climbing, bouldering, and ice climbing within • Protect the backcountry and wilderness the Park. experiences of other Park visitors. Rules & Regulations Prohibited Activities: Fixed Anchors (including belay/rappel • Using motorized equipment to place bolts, stations): anchors or climbing equipment Fixed anchors are prohibited in all locations • Chipping or gluing. where temporary, removable protection can be • Removing vegetation to “clean” or improve a used. The installation of fixed anchors should route, or access to a route. be rare parkwide, especially in wilderness areas. • Leaving fixed ropes or other equipment for longer than 24 hours. Group Size Limits: • Using non-climbing specific hardware (i.e., Groups may contain a maximum of 12 people. concrete anchors, home-made equipment). Emergency 1-800-732-0911 • Information 540-999-3500 • Online www.nps.gov/shen Rules & Regulations If forced to install a fixed belay and/or Trees as Anchors: (continued) rappel station, follow these rules: Do not cause physical damage to trees or plants. -

Jeremy's Run Hike

Jeremy's Run Hike Jeremy's Run Mountain - SNP, Virginia Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 14.7 mls Hiking Time: 6.5 hours with a half hour for lunch Elev. Gain: 2,620 ft Parking: Turn off Skyline Drive into the Elkwallow Picnic Grounds and park at the far end and Jeremy's Run Trailhead sign. At 14.7 miles the Jeremy's Run loop is one of the longest in the SNP. On the Neighbor Mountain Trail there are several beautiful views to the west of Kennedy Peak, Duncan Knob, and the Three Sisters Ridge just to the south. Also with 14 crossings of Jeremy's Run this hike can be a challenge in the spring when the water is at its highest level. From the parking area start down the connector trail where it shortly joins the white blazed Appalachian Trail (AT). Continue downward on the white blazed AT and in 0.3 miles arrive at the intersection of the blue blazed Jeremy's Run Trail that continues downward. Turn left remaining on the white blazed AT as it it climbs Blue Ridge. In 2.3 miles from the Jeremy's Run intersection arrive at the Blue Ridge high point, and a trail intersection that leads to the Thorton River Trail. Remain south/straight on the white blazed AT following the ridgeline for another 1.3 miles to the next intersection that leads to a Skyline Drive parking area. Again stay on the AT, and in 0.2 miles reach the four way intersection with the Neighbor Mountain Trail. -

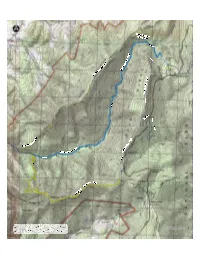

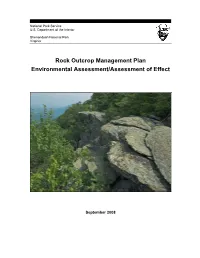

Rock Outcrop Management Plan Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Shenandoah National Park Virginia Rock Outcrop Management Plan Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect September 2008 This page intentionally left blank Cover photo courtesy of Gary P. Fleming National Park Service Rock Outcrop Management Plan Shenandoah National Park Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Rock Outcrop Management Plan Environmental Assessment / Assessment of Effect Shenandoah National Park Luray, Page County, Virginia SUMMARY Proposed Action: : Shenandoah National Park has prepared this Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect to analyze alternatives related to direct the future management of rock outcrop areas in the Park. The purpose of taking this action is to address the need to protect, restore, and perpetuate rock outcrops and natural resources associated with the outcrops while providing a range of recreational opportunities for visitors to experience. Several feasible alternatives were considered. Alternative B, the NPS preferred alternative, proposed to establish a balance between natural resource protection and visitor use. Actions under this alternative would allow visitor use of selected rock outcrop areas while minimizing impacts to natural resource conditions. Implementing the preferred alternative would have negligible to moderate impacts to geological and soil resources, ecological communities, rare, threatened and endangered plants, rare, threatened or endangered species, wilderness