Scenic Design for the Last Days of Judas Iscariot by Stephen Adly Guirgis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study in Bitter Remorse (John 12: 1-8)

1 A Study in Bitter Remorse (John 12: 1-8) Today we continue the ancient church season of Lent. The word Lent is derived from the Anglo-Saxon words lencten, meaning "Spring," and lenctentid, which literally means "Springtide" and is also the word used for "March," the month in which the majority of Lent falls. The season of Lent includes 40 days (not counting Sundays) before Easter. Our Roman Catholic friends have been observing this season for much longer than we Protestants. But during my lifetime (41 years) there has been a shift of embracing many of these older church traditions. The number "40" has always had special significance concerning preparation. You’ll remember that on Mount Sinai, preparing to receive the Ten Commandments, "Moses stayed with the Lord for 40 days and 40 nights, without eating any food or drinking any water" (Ex 34:28). Also, that Elijah walked "40 days and 40 nights" to the mountain of the Lord, Mount Horeb (another name for Sinai) (I Kgs 19:8). And most importantly, Jesus fasted and prayed for "40 days and 40 nights" in the desert before He began His public ministry (Mt 4:2). Many churches encourage its members to refrain from something for 40 days that they would otherwise indulge in *story about Maggie and chocolate* People often withhold food/some activity so as to feel closer to the weight of the cross. Speaking of the cross… The cross you see before you this morning is on loan from our friends… For Lent, I will be doing a series called, “The faces of the cross”, each Sunday and Wednesday we will reflect upon a new “face” that contributed in some way to the events of Holy week. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Paul Or Matthias: Who Was the Real 12Th Apostle?

Paul or Matthias: Who Was the Real 12 th Apostle? Ep.1113 – February 17, 2020 Paul or Matthias: Who Was the Real 12th Apostle? Contradiction Series Acts 1:21-22: (NASB) 21 Therefore it is necessary that of the men who have accompanied us all the time that the Lord Jesus went in and out among us 22 …one of these must become a witness with us of his resurrection. For every Christian, Jesus is THE example, leader and fulfiller of our faith. We continually gain inspiration from his perfect example and unselfish sacrifice. When we think about a less- than-perfect Christian example, most of us go to the Apostle Peter or the Apostle Paul. Both men showed us how to achieve spiritual victory through imperfection. They both had failures, they both had regrets, they both had doubts, and yet they were faithful. These challenges endear them to our hearts and give us courage to work through our own imperfect experiences. Knowing this, it can be hard to believe there are many who see the Apostle Paul as an interloper, one who hijacked the gospel message. These accusations begin with disregarding the authenticity of Paul’s apostleship. They say Matthias, as a replacement for Judas, was appointed as the 12th Apostle long before Paul’s conversion. We started our four-part series on contradictions with things Paul said or did that require a second look: Ep.1111: Does the Apostle Paul Contradict Himself? (Part I) Ep.1112: Does the Apostle Paul Contradict Himself? (Part II) This podcast is a special foundational program. -

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706 FILM DOLLFACE Department Head Hair/ Hulu Personal Hair Stylist To Kat Dennings THE HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Camp Sugar Director: Chris Addison SERENITY Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Global Road Entertainment Director: Steven Knight ALPHA Department Head Studio 8 Director: Albert Hughes Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson, Jens Hultén THE CIRCLE Department Head 1978 Films Director: James Ponsoldt Cast: Emma Watson, Tom Hanks LOVE THE COOPERS Hair Designer To Marisa Tomei CBS Films Director: Jessie Nelson CONCUSSION Department Head LStar Capital Director: Peter Landesman Cast: Gugu Mbatha-Raw, David Morse, Alec Baldwin, Luke Wilson, Paul Reiser, Arliss Howard BLACKHAT Department Head Forward Pass Director: Michael Mann Cast: Viola Davis, Wei Tang, Leehom Wang, John Ortiz, Ritchie Coster FOXCATCHER Department Head Annapurna Pictures Director: Bennett Miller Cast: Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Siena Miller, Vanessa Redgrave Winner: Variety Artisan Award for Outstanding Work in Hair and Make-Up THE MILTON AGENCY Kathrine Gordon 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 and 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 6 AMERICAN HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist to Christian Bale, Amy Adams/ Columbia Pictures Corporation Hair/Wig Designer for Jennifer Lawrence/ Hair Designer for Jeremy Renner Director: David O. Russell -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Production Notes

A Film by John Madden Production Notes Synopsis Even the best secret agents carry a debt from a past mission. Rachel Singer must now face up to hers… Filmed on location in Tel Aviv, the U.K., and Budapest, the espionage thriller The Debt is directed by Academy Award nominee John Madden (Shakespeare in Love). The screenplay, by Matthew Vaughn & Jane Goldman and Peter Straughan, is adapted from the 2007 Israeli film Ha-Hov [The Debt]. At the 2011 Beaune International Thriller Film Festival, The Debt was honoured with the Special Police [Jury] Prize. The story begins in 1997, as shocking news reaches retired Mossad secret agents Rachel (played by Academy Award winner Helen Mirren) and Stephan (two-time Academy Award nominee Tom Wilkinson) about their former colleague David (Ciarán Hinds of the upcoming Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). All three have been venerated for decades by Israel because of the secret mission that they embarked on for their country back in 1965-1966, when the trio (portrayed, respectively, by Jessica Chastain [The Tree of Life, The Help], Marton Csokas [The Lord of the Rings, Dream House], and Sam Worthington [Avatar, Clash of the Titans]) tracked down Nazi war criminal Dieter Vogel (Jesper Christensen of Casino Royale and Quantum of Solace), the feared Surgeon of Birkenau, in East Berlin. While Rachel found herself grappling with romantic feelings during the mission, the net around Vogel was tightened by using her as bait. At great risk, and at considerable personal cost, the team’s mission was accomplished – or was it? The suspense builds in and across two different time periods, with startling action and surprising revelations that compel Rachel to take matters into her own hands. -

Jesus Breathed on Them. Does That Strike You As Strange?

Jesus Breathed Jesus breathed on them. Does that strike you as strange? When you greet your family or friends, do you breathe on them? Maybe you shake hands; maybe you hug them; maybe you even give them a kiss on the cheek. Some of us like to give high fives or fist bumps. Eskimos rub noses; Japanese bow to each other. But have you ever heard of greeting your friends by breathing on them? John tells us that Jesus breathed on his disciples. Why did he do this? Did Jesus exhale one really big breath that reached all the disciples in the room, or did he breathe on each one individually? John doesn't tell us how many breaths Jesus breathed on the disciples, but I think he breathed on each one individually, one at a time, looking each one in the eyes, maybe resting his wounded hands on each one's shoulders while he breathed a divine breath on each disciple's face, a breath that entered each disciple's nostrils. Why did Jesus do this? As he breathed on them, he said, "Peace be with you; receive the Holy Spirit." Peace and the Holy Spirit carried on the breath of Jesus. What's so special about breath? The Bible teaches us that breath is something holy and sacred. In the book of Genesis, "The Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being. In the book of Job, Job says, "The spirit of God has made me, and the breath of the Almighty gives me life." In the book of Ezekiel, the prophet sees a valley filled with dry bones. -

American Gangster

www.kirkeogfilm.dk American gangster Gangstermiljøet og et helt samfund i Vietnamkrigens lys Af Jes Nysten Filmen henter sit stof fra en autentisk historie, som udspilledes i slutningen af 60’ernes New York. Vi er i Vietnamkrigens og hippietidens USA. Hvor negrenes kamp for ligestilling var i fuld gang, og hvor Harlem stadig var totalt ’sort’ område. Frank Lucas har med alle midler – og jeg mener alle midler – gjort sig til ’godfather’ for et stort område i Harlem. Derudover har han egenhændig etableret sig som importør af ren heroin fra Vietnam, som han sælger og på den måde samler sig en enorm formue, som bl.a. bruges på generøse gaver til hans ’undersåtter’ i Harlems gader. Men han samler også sin familie omkring sig, for det er netop det, der gælder: social status og ubrydeligt familiesammenhold, uanset hvordan man opnår denne formue og status. Frank bryder således med de gængse spilleregler og kommer på den måde til at skulle krydse klinger med folk, der normalt sidder sikkert på narkomarkedet: de etablerede mafiafamilier og byens korrupte politifolk. Men den afgørende kamp for Frank kommer til at stå med den lidt forhutlede men bundhæderlige politimand Richie Roberts. -1- www.kirkeogfilm.dk På klassisk vis løber filmen i to spor, nemnlig disse to mænds i begyndelsen separate historier, som langsomt nærmer sig hinanden; og som først til allersidst løber sammen i den klassiske konfrontation: helten overfor skurken! Et møde som imidlertid får et temmelig ukonventionel efterspil, som ikke skal røbes her. Som nævnt bruges gangstergenren som et stærkt stiliseret billede på de gængse spilleregler i samfundet - sådan også her. -

Gospel of Barnabas

Facsimile of the original Title page THE GOSPEL OF BARNABAS EDITED AND TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN MS. IN THE IMPERIAL LIBRARY AT VIENNA BY LONSDALE AND LAURA RAGG WITH A FACSIMILE OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1907 May the light of the Gospel of Barnabas illuminate The Gospel of Barnabas Contents Pages 1, Introduction V 2. Barnabas in the New Testament vii 3. Life and Message of Barnabas x 4. The Gospel of Jesus 5. How the Gospel of Barnabas Appendix I 274 Survived 6. Unitarianism in the Bible II 275 7. Mohammad in the Bible III 278 8. Jesus in the Bible IV 283 9. Facts About Other Gospels Veracity in the Gospel V 286 10. The Holy Prophet Mohammad Foretold in Ancient Scriptures. VI 287 28728 What Christian Authorities Say 11. about The Myth of God Incarnate- Gospel masked in Greek Philosophy. t, „ VII 297 12. Testimonies from the Bibles to the Quranic Truth that Jesus is not God.' ,. VIII 299 www.islamicbulletin.com INTRODUCTION The Holy Quran asks us not only to believe in our Holy Prophet but also in the prophets who had come prior to his advent. We, Muslims, are interested not only in the Revelation that was given to humanity through our Prophet, but also, in the Revelations which were given to prophets previous to him. Among the prophet's who had appeared before our Holy Prophet, the Quran has emphasized the importance to the Muslims of Prophet Jesus. Jesus was no doubt sent with a mission to the Israelites; he had also a universal mission. -

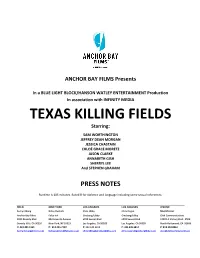

TEXAS KILLING FIELDS Starring

ANCHOR BAY FILMS Presents In a BLUE LIGHT BLOCK/HANSON WATLEY ENTERTAINMENT Production In association with INFINITY MEDIA TEXAS KILLING FIELDS Starring: SAM WORTHINGTON JEFFREY DEAN MORGAN JESSICA CHASTAIN CHLOЁ GRACE MORETZ JASON CLARKE ANNABETH GISH SHERRYL LEE And STEPHEN GRAHAM PRESS NOTES Runtime is 105 minutes. Rated R for violence and language including some sexual references. FIELD NEW YORK LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES ONLINE Sumyi Khong Betsy Rudnick Chris Libby Chris Regan Mac McLean Anchor Bay Films Falco Ink Ginsberg/Libby Ginsberg/Libby Click Communications 9242 Beverly Blvd 850 Seventh Avenue 6255 Sunset Blvd 6255 Sunset Blvd 13029-A Victory Blvd., #509 Beverly Hills, CA 90210 New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90028 Los Angeles, CA 90028 North Hollywood, CA 91606 P: 424.204.4164 P: 212.445.7100 P: 323.645.6812 P: 323.645.6814 P: 818.392.8863 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] mac@clickcommunications TEXAS KILLING FIELDS Synopsis Inspired by true events, this tense and haunting thriller follows Detective Souder (Sam Worthington), a homicide detective in a small Texan town, and his partner, transplanted New York City cop Detective Heigh (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) as they track a sadistic serial killer dumping his victims’ mutilated bodies in a nearby marsh locals call “The Killing Fields.” Though the swampland crime scenes are outside their jurisdiction, Detective Heigh is unable to turn his back on solving the gruesome murders. Despite his partner’s warnings, he sets out to investigate the crimes. Before long, the killer changes the game and begins hunting the detectives, teasing them with possible clues at the crime scenes while always remaining one step ahead. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

The Holy See

The Holy See BENEDICT XVI GENERAL AUDIENCE Saint Peter's Square Wednesday, 18 October 2006 Judas Iscariot and Matthias Dear Brothers and Sisters, Today, concluding our walk through the portrait gallery of the Apostles called directly by Jesus during his earthly life, we cannot fail to mention the one who has always been named last in the list of the Twelve: Judas Iscariot. We want to associate him with the person who is later elected to substitute him, Matthias. Already the very name of Judas raises among Christians an instinctive reaction of criticism and condemnation. The meaning of the name "Judas" is controversial: the more common explanation considers him as a "man from Kerioth", referring to his village of origin situated near Hebron and mentioned twice in Sacred Scripture (cf. Gn 15: 25; Am 2: 2). Others interpret it as a variant of the term "hired assassin", as if to allude to a warrior armed with a dagger, in Latin, sica. Lastly, there are those who see in the label a simple inscription of a Hebrew-Aramaic root meaning: "the one who is to hand him over". This designation is found twice in the Gospel: after Peter's confession of faith (cf. Jn 6: 71), and then in the course of the anointing at Bethany (cf. Jn 12: 4). Another passage shows that the betrayal was underway, saying: "he who betrayed him"; and also 2 during the Last Supper, after the announcement of the betrayal (cf. Mt 26: 25), and then at the moment of Jesus' arrest (cf. Mt 26: 46, 48; Jn 18: 2, 5).