The Construction of Frontier Masculinity in Latenineteenth And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annie Oakley Topic Guide for Chronicling America (

Annie Oakley Topic Guide for Chronicling America (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov) Introduction Annie Oakley (1860-1926) was an American sharpshooter and exhibition shooter born in Darke County, Ohio, as Phoebe Ann Mosey. When she was five, her father died, and Annie learned to trap, shoot and hunt by age eight to help support her family. In 1875 (though some sources say it was in 1881), Annie met her future husband, Frank E. Butler, at the Baughman & Butler shooting act in Cincinnati, while beating him in a shooting contest. They were married a year later, and in 1885, they joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West where she was given the nickname “Little Sure Shot.” Considered America’s first female star, Oakley traveled all over the United States and Europe showing off her skills. Oakley set shooting records into her sixties, and also did philanthropic work for women’s rights and other causes. In 1925, she died in Greenville, Ohio. Important Dates . August 13, 1860: Annie Oakley is born Phoebe Ann Mosey in Darke County, Ohio. November 1875: Oakley defeats Frank E. Butler in a shooting contest. The pair marries a year later. 1885: Oakley and Butler join Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. 1889: Oakley travels to France to perform in the Paris Exposition. 1901: Oakley is injured in a train accident but recovers and returns to show business. 1912-1917: Oakley and Butler retire temporarily and reside in Cambridge, Maryland. 1917: Oakley and Butler move to North Carolina and return to public life. 1922: Oakley and Butler are injured in a car accident, but Oakley performs again a year or so later. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

Frontier Culture: the Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse NBER Working Paper No

Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse NBER Working Paper No. 23997 November 2017, Revised August 2020 JEL No. D72,H2,N31,N91,P16 ABSTRACT The presence of a westward-moving frontier of settlement shaped early U.S. history. In 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner famously argued that the American frontier fostered individualism. We investigate the Frontier Thesis and identify its long-run implications for culture and politics. We track the frontier throughout the 1790–1890 period and construct a novel, county-level measure of total frontier experience (TFE). Historically, frontier locations had distinctive demographics and greater individualism. Long after the closing of the frontier, counties with greater TFE exhibit more pervasive individualism and opposition to redistribution. This pattern cuts across known divides in the U.S., including urban–rural and north–south. We provide evidence on the roots of frontier culture, identifying both selective migration and a causal effect of frontier exposure on individualism. Overall, our findings shed new light on the frontier’s persistent legacy of rugged individualism. Samuel Bazzi Mesay Gebresilasse Department of Economics Amherst College Boston University 301 Converse Hall 270 Bay State Road Amherst, MA 01002 Boston, MA 02215 [email protected] and CEPR and also NBER [email protected] Martin Fiszbein Department of Economics Boston University 270 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 and NBER [email protected] Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States∗ Samuel Bazziy Martin Fiszbeinz Mesay Gebresilassex Boston University Boston University Amherst College NBER and CEPR and NBER July 2020 Abstract The presence of a westward-moving frontier of settlement shaped early U.S. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

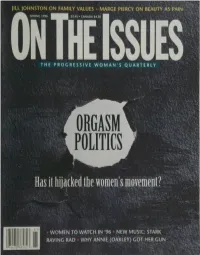

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

NORMAN K Denzin Sacagawea's Nickname1, Or the Sacagawea

NORMAN K DENZIN Sacagawea’s Nickname1, or The Sacagawea Problem The tropical emotion that has created a legendary Sacajawea awaits study...Few others have had so much sentimental fantasy expended on them. A good many men who have written about her...have obviously fallen in love with her. Almost every woman who has written about her has become Sacajawea in her inner reverie (DeVoto, 195, p. 618; see also Waldo, 1978, p. xii). Anyway, what it all comes down to is this: the story of Sacagawea...can be told a lot of different ways (Allen, 1984, p. 4). Many millions of Native American women have lived and died...and yet, until quite recently, only two – Pocahantas and Sacagawea – have left even faint tracings of their personalities on history (McMurtry, 001, p. 155). PROLOGUE 1 THE CAMERA EYE (1) 2: Introduction: Voice 1: Narrator-as-Dramatist This essay3 is a co-performance text, a four-act play – with act one and four presented here – that builds on and extends the performance texts presented in Denzin (004, 005).4 “Sacagawea’s Nickname, or the Sacagawea Problem” enacts a critical cultural politics concerning Native American women and their presence in the Lewis and Clark Journals. It is another telling of how critical race theory and critical pedagogy meet popular history. The revisionist history at hand is the history of Sacagawea and the representation of Native American women in two cultural and symbolic landscapes: the expedition journals, and Montana’s most famous novel, A B Guthrie, Jr.’s mid-century novel (1947), Big Sky (Blew, 1988, p. -

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOSEVELT, THEODORE 1858-1919 Gift of Paul C. Richards, 1976-1990; 1993 Note: Items found in Richards-Roosevelt Room Case are identified as such with the notation ‘[Richards-Roosevelt Room]’. Boxes 1-12 I. Correspondence Correspondence is listed alphabetically but filed chronologically in Boxes 1-11 as noted below. Material filed in Box 12 is noted as such with the notation “(Box 12)”. Box 1 Undated materials and 1881-1893 Box 2 1894-1897 Box 3 1898-1900 Box 4 1901-1903 Box 5 1904-1905 Box 6 1906-1907 Box 7 1908-1909 Box 8 1910 Box 9 1911-1912 Box 10 1913-1915 Box 11 1916-1918 Box 12 TR’s Family’s Personal and Business Correspondence, and letters about TR post- January 6th, 1919 (TR’s death). A. From TR Abbott, Ernest H[amlin] TLS, Feb. 3, 1915 (New York), 1 p. Abbott, Lawrence F[raser] TLS, July 14, 1908 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. ALS, Dec. 2, 1909 (on safari), 4 p. TLS, May 4, 1916 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. TLS, March 15, 1917 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. Abbott, Rev. Dr. Lyman TLS, June 19, 1903 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Nov. 21, 1904 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Feb. 15, 1909 (Washington, D.C.), 2 p. Aberdeen, Lady ALS, Jan. 14, 1918 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. Ackerman, Ernest R. TLS, Nov. 1, 1907 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. Addison, James T[hayer] TLS, Dec. 7, 1915 (Oyster Bay), 1p. Adee, Alvey A[ugustus] TLS, Oct. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Nebraska's Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World Full Citation: William E Deahl Jr, “Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World,” Nebraska History 49 (1968): 282-297 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1968Entertainment.pdf Date: 11/23/2015 Article Summary: Buffalo Bill Cody and Dr. W F Carver were not the first to mount a Wild West show, but their opening performances in 1883 were the first truly successful entertainments of that type. Their varied acts attracted audiences familiar with Cody and his adventures. Cataloging Information: Names: William F Cody, W F Carver, James Butler Hickok, P T Barnum, Sidney Barnett, Ned Buntline (Edward Zane Carroll Judson), Joseph G McCoy, Nate Salsbury, Frank North, A H Bogardus Nebraska Place Names: Omaha Wild West Shows: Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition -

The Baxter's Curve Train Robbery

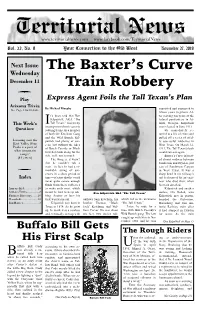

Territorial News www.territorialnews.com www.facebook.com/TerritorialNews Vol. 33, No. 9 Your Connection to the Old West November 27, 2019 Next Issue The Baxter’s Curve Wednesday December 11 Train Robbery Play Express Agent Foils the Tall Texan’s Plan Arizona Trivia By Michael Murphy convicted and sentenced to See Page 2 for Details fifteen years in prison. Af- t’s been said that Ben ter serving ten years at the Kilpatrick, AKA “The federal penitentiary in At- This Week’s I Tall Texan,” was pretty lanta, Georgia, Kilpatrick incompetent when it came to was released in June 1911. Question: robbing trains. As a member He immediately re- of both the Ketchum Gang turned to a life of crime and and the Wild Bunch, Kil- pulled off a series of mild- Looming over the patrick had plenty of suc- ly successful robberies in East Valley, Four cess, but without the likes West Texas. On March 12, Peaks is a part of of Butch Cassidy or Black 1912, The Tall Texan’s luck what mountain Jack Ketchum along for the would run out again. range? ride, well, not so much. Baxter’s Curve is locat- (8 Letters) The thing is, it wasn’t ed almost midway between that he couldn’t rob a Sanderson and Dryden, just train—in fact he had a re- east of Sanderson Canyon markable string of suc- in West Texas. It was a cesses in a short period of sharp bend in the railway’s Index time—it’s just that he could rail bed named for an engi- never quite secure enough neer who died there when funds from these robberies his train derailed. -

THE FRONTIER in AMERICAN CULTURE (HIS 324-01) University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Spring 2014 Tuesday and Thursday 3:30-4:45Pm ~ Curry 238

THE FRONTIER IN AMERICAN CULTURE (HIS 324-01) University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Spring 2014 Tuesday and Thursday 3:30-4:45pm ~ Curry 238 Instructor: Ms. Sarah E. McCartney Email: [email protected] (may appear as [email protected]) Office: MHRA 3103 Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday from 2:15pm-3:15pm and by appointment Mailbox: MHRA 2118A Course Description: Albert Bierstadt, Emigrants Crossing the Plains (1867). This course explores the ways that ideas about the frontier and the lived experience of the frontier have shaped American culture from the earliest days of settlement through the twenty- first century. Though there will be a good deal of information about the history of western expansion, politics, and the settlement of the West, the course is designed primarily to explore the variety of meanings the frontier has held for different generations of Americans. Thus, in addition to settlers, politicians, and Native Americans, you will encounter artists, writers, filmmakers, and an assortment of pop culture heroes and villains. History is more than a set of facts brought out of the archives and presented as “the way things were;” it is a careful construction held together with the help of hypotheses and assumptions.1 Therefore, this course will also examine the “construction” of history as you analyze primary sources, discuss debates in secondary works written by historians, and use both primary and secondary sources to create your own interpretation of history. Required Texts: Robert V. Hine and John Mack Faragher. Frontiers: A Short History of the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. -

2020 Benefit Art Auction

THE MISSOULA ART MUSEUM ANNUAL BENEFIT ART AUCTION CREATIVITY TAKES COURAGE. Henri Matisse We’re honored to support the Missoula Art Museum, because creativity is contagious. DESIGN WEBSITES MARKETING PUBLIC RELATIONS CONTACT CENTER 406.829.8200 WINDFALLSTUDIO.COM 2 SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2020 UC Ballroom, University of Montana 5 PM Cocktails + Silent Auction Opens 6 PM Dinner 7 PM Live Auction 7:45 PM Silent Auction Round 2 Closes 8:45 PM Silent Auction Round 3 Closes Celebrating 45 Years of MAM PRESENTING SPONSOR Auctioneer: Johnna Wells, Benefit Auctions 360, LLC Portland, Oregon Printing services provided by Advanced Litho. MEDIA SPONSORS EVENT SPONSORS Missoula Broadcasting Missoula Wine Merchants Mountain Broadcasting University Center and UM Catering The Missoulian ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to the many businesses that have donated funds, services, and products to make the auction exhibition, live events, and special programs memorable. Support the businesses that support MAM. Thank you to all of the auction bidders and attendees for directly supporting MAM’s programs. Thank you to the dozens of volunteers who help operate the museum and have contributed additional time, energy, and creativity to make this important event a success. 1 You’re going to need more wall space. Whether you’re upsizing, downsizing, buying your dream home, or moving to the lake, our agents will treat you just like a neighbor because, well, you are one. Their community-centric approach and local expertise make all the difference. WINDERMEREMISSOULA.COM | (406) 541-6550 | 2800 S. RESERVE ST. 2 WELCOME On behalf of the 2020 Benefit Art Auction Committee! We are proud to support MAM’s commitment to free expression and free admission, and we are honored that artists and art lovers alike have come together to celebrate Missoula’s art community.