MYSTICAL GEOGRAPHIES of CORNWALL Carl Phillips Thesis Submitted to the University of Nottingham for the Degree of Doctor of Phil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minewater Study

National Rivers Authority (South Western-Region).__ Croftef Minewater Study Final Report CONSULTING ' ENGINEERS;. NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY SOUTH WESTERN REGION SOUTH CROFTY MINEWATER STUDY FINAL REPORT KNIGHT PIESOLD & PARTNERS Kanthack House Station Road September 1994 Ashford Kent 10995\r8065\MC\P JS TN23 1PP ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 125218 r:\10995\f8065\fp.Wp5 National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY -1- 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 2. THE SOUTH CROFTY MINE 2-1 2.1 Location____________________________________________________ 2-1 ________2.2 _ Mfning J4istojy_______________________________________ ________2-1. 2.3 Geology 2-1 2.4 Mine Operation 2-2 3. HYDROLOGY 3-1 3.1 Groundwater 3-1 3.2 Surface Water 3-1 3.3 Adit Drainage 3-2 3.3.1 Dolcoath Deep and Penhale Adits 3-3 3.3.2 Shallow/Pool Adit 3-4 3.3.3 Barncoose Adit 3-5 4. MINE DEWATERING 4-1 4.1 Mine Inflows 4-1 4.2 Pumped Outflows 4-2 4.3 Relationship of Rainfall to Pumped Discharge 4-3 4.4 Regional Impact of Dewatering 4-4 4.5 Dewatered Yield 4-5 4.5.1 Void Estimates from Mine Plans 4-5 4.5.2 Void Estimate from Production Tonnages 4-6 5. MINEWATER QUALITY 5-1 5.1 Connate Water 5-2 5.2 South Crofty Discharge 5-3 5.3 Adit Water 5-4 5.4 Acidic Minewater 5-5 Knif»ht Piesold :\10995\r8065\contants.Wp5 (l) consulting enCneers National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS (continued) Page 6. -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales Cymorth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Winifred Coombe Tennant Papers, (GB 0210 WINCOOANT) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/winifred-coombe-tennant-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/winifred-coombe-tennant-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Winifred Coombe Tennant Papers, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Community Network Member Electoral Division Organisation / Project Grant Description Grant Amount Year West Penwith Dwelly T

Community Grant Member Electoral Division Organisation / Project Grant Description Year Network Amount Penwith Community Radio Penwith Radio FM West Penwith Dwelly T Penzance East £200.00 2014/15 Station broadcasting project Christmas Workshops and West Penwith Dwelly T Penzance East Pop Up Penzance £100.00 2014/15 window Gulval Church Cross West Penwith Fonk M Gulval & Heamoor Gulval Christmas Lights £276.00 2014/15 Upgrade Penwith Community Radio Penwith Radio FM West Penwith Fonk M Gulval & Heamoor £300.00 2014/15 Station broadcasting project Christmas Workshops and West Penwith Fonk M Gulval & Heamoor Pop Up Penzance £100.00 2014/15 window Paul Village Christmas tree West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Hutchens House Paul £150.00 2014/15 project Safety Improvements to West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Mousehole Christmas Lights £300.00 2014/15 equipment trailer Research & Recording Mousehole Historic Research & West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Mousehole 1810 as a £100.00 2014/15 Archive Society Pilotage Port Making the digital archive West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Newlyn Archive £100.00 2014/15 more accessible to visitors West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Newlyn Harbour Lights Xmas Lights 2014 £150.00 2014/15 West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Tredavoe Chapel Trust Christmas trees £150.00 2014/15 Community Grant Member Electoral Division Organisation / Project Grant Description Year Network Amount Penwith Community Radio Penwith Radio FM West Penwith James S St Just in Penwith £200.00 -

The Distribution of Ammonium in Granites from South-West England

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 145, 1988, pp. 37-41, 1 fig., 5 tables. Printed in Northern Ireland The distribution of ammonium in granites from South-West England A. HALL Department of Geology, Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX, UK Abstract: The ammonium contents of granites, pegmatites and hydrothermally altered rocks from SW England have been measured. Ammonium levels in the granites are generally high compared with those from other regions, averaging 36ppm,and they differ markedlybetween intrusions. The pegmatites show higherammonium contents than any other igneous rocks which have yet been investigated. Ammonium contents are strongly enriched in the hydrothermally altered rocks, includ- ing greisens and kaolinized granites. There is agood correlation between the average ammonium content of the intrusions in SW England and their initial "Sr/*'Sr ratios and peraluminosity. This relationship supports the hypothesis that the ammonium in the granites is derived from a sedimentary source, either in the magmatic source region or via contamination of the magma. Introduction Results Ammonium is present as a trace constituent of granitic The granites rocks, in which it occurs in feldspars and micas substituting isomorphously for potassium (Honma & Itihara 1981). The The new analyses of Cornubian granites are given in Table amount of ammonium in granites varies from zero to over 1. They show a range of 3-179 parts per million NH:, with 100 parts per million, and it has been suggested that high the highest values being found in relatively small intrusions. concentrations may indicate the incorporation of organic- Taking the averagefor each of the major intrusions,and rich sedimentary material into the magma, either from the weighting them according to their relative areas (see Table presence of such material in rhe magmatic source region or 4), the average ammonium contentof the Cornubian granites via the assimilation of organic-rich country rocks (Urano as a whole is 36 ppm. -

Statement of Parties and Individual Candidates Nominated

European Parliamentary Election for the South West Region - 4th June 2009 STATEMENT OF PARTIES AND INDIVIDUAL CANDIDATES NOMINATED 1. The following parties and individual candidates have been and stand nominated: British National Jeremy Edward Barry John Sinclair Adrian Llewellyn Romilly Sean Derrick Twitchin Lawrence Reginald West Peryn Walter Parsons Wotherspoon Bennett 66 College Avenue, 15 Autumn Road, Poole, 27 Lutyens Drive, 12 Simons Close, Worle, Party British National 15 Tremlett Grove, 64 Castlemain Avenue, Mutley, Plymouth Dorset BH11 8TF Paignton, Devon Weston super Mare, Party - Protecting Ipplepen, Newton Abbot, Southbourne, Bournemouth , PL4 7AP TQ3 3LA North Somerset British Jobs Devon TQ12 5BZ Dorset BH6 5EN BS22 6DJ Christian Party William Patrick Capstick Katherine Susan Mills Diana Ama Ofori Larna Jane Martin Peter Vickers Adenike Williams 38 Winton Avenue, 7 Wellington Road, 32 New Plaistow Road, 27 Clonmore Street, 96 Blaker Court, 5 Hensley Point, "Proclaiming London Wanstead, London Stratford, London Southfield, London Fairlawn, London Bradstock Road, Christ's Lordship" N11 2AT E11 2AN E15 3JB SW18 5EU SE7 7ET London E9 5BE The Christian Party - CPA Conservative Giles Bryan Chichester Julie McCulloch Girling Ashley Peter Fox Michael John Edward Donald John Collier Syeda Zehra Zaidi Longridge, West Hill, The Knapp, Dovers Hill, 77 Park Grove, Henleaze, Dolley 22 Douglas Road, Poole, Nupend Lodge, Nupend Party Ottery St Mary, Devon Chipping Campden, Bristol BS9 4NY Leeside, West Street, Dorset BH12 2AX Lane, Longhope, -

Agenda-Thursday-06Th-February-2020-Website

MADRON PARISH COUNCIL Chairman Mr Vic Peake Website: www.madron.org Clerk to the Council Trannack Farm Mrs J Ellis St Erth Tel: 07855774357 Hayle E-mail: [email protected] TR27 6ET Ordinary Meeting of Madron Parish Council to be held at Trythall CP School on Thursday 06th February 2020, at 7.30pm Dear Councillor, You are requested to attend the meeting at the time and date shown above. Mrs J Ellis, Clerk. AGENDA 1. Apologies 2. Acceptance of Minutes Ordinary meeting held on 02nd January 2020 at Landithy Community Rooms. 3. Declarations of interest in items on this agenda 4. Dispensations 5. Public Participation 6. Chairman’s Comments 7. Councillor's Questions and Comments - (24 hours notice to clerk advisable) 8. Comments from Cornwall Councillors 9. Planning Applications: PA18/02055 - Land at Tregoddick Farm, Vingoes Lane Madron – Outline Planning Application for 17 dwellings. PA20/00072 - Rosemorran Farm Road from Popworks Hill to Helnoweth Gulval TR20 8YS - Erection of an agricultural storage shed. PA19/10464 - Redundant Barn Hellangove Farm Gulval Penzance Cornwall TR20 8XD - Conversion of agricultural barn to form dwelling house – Amended Plans. PA19/10777 - Trebean Fore Street Madron TR20 8SH - Construction of garage, store and studio as re- submission of PA19/07377. Approved: PA19/09335 - Bone Farm Access To Bone Farm Heamoor TR20 8UJ - Application of reserved matters following outline approval PA14/09985 dated 19.12.2014: Access Appearance Layout Scale and Landscaping: Variation of condition 1 in relation to decision notice PA15/1134. PA19/09763 - Polkinghorne Cottage, The Chalet Access To Boscobba Gulval TR20 8YS - Proposed single- storey Extension to existing Chalet. -

Diocese of Truro with the Green Church Kernow Award Scheme

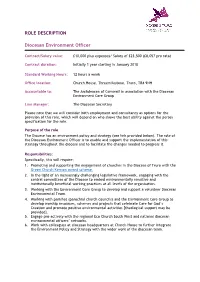

ROLE DESCRIPTION Diocesan Environment Officer Contract/Salary value: £10,000 plus expenses/ Salary of £23,500 (£8,057 pro rata) Contract duration: Initially 1 year starting in January 2018 Standard Working Hours: 12 hours a week Office location: Church House, Threemilestone, Truro, TR4 9NH Accountable to: The Archdeacon of Cornwall in association with the Diocesan Environment Core Group Line Manager: The Diocesan Secretary Please note that we will consider both employment and consultancy as options for the provision of this role, which will depend on who shows the best ability against the person specification for the role. Purpose of the role The Diocese has an environment policy and strategy (see link provided below). The role of the Diocesan Environment Officer is to enable and support the implementation of this strategy throughout the diocese and to facilitate the changes needed to progress it. Responsibilities: Specifically, this will require: 1. Promoting and supporting the engagement of churches in the Diocese of Truro with the Green Church Kernow award scheme. 2. In the light of an increasingly challenging legislative framework, engaging with the central committees of the Diocese to embed environmentally sensitive and institutionally beneficial working practices at all levels of the organisation. 3. Working with the Environment Core Group to develop and support a volunteer Diocesan Environmental Team. 4. Working with parishes (parochial church councils) and the Environment Core Group to develop worship resources, schemes and projects that celebrate Care for God’s Creation and promote positive environmental activities [theological support may be provided]. 5. Engage pro-actively with the regional Eco Church South West and national diocesan environmental officers’ networks. -

The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales

Volume 3 │ Issue 1 │ 2018 The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales McKinley Terry Abilene Christian University Texas Psi Chapter Vol. 3(1), 2018 Article Title: The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales DOI: 10.21081/AX0173 ISSN: 2381-800X Key Words: Wales, poets, 20th Century, World War I, memorials, bards This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Author contact information is available from the Editor at [email protected]. Aletheia—The Alpha Chi Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship • This publication is an online, peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary undergraduate journal, whose mission is to promote high quality research and scholarship among undergraduates by showcasing exemplary work. • Submissions can be in any basic or applied field of study, including the physical and life sciences, the social sciences, the humanities, education, engineering, and the arts. • Publication in Aletheia will recognize students who excel academically and foster mentor/mentee relationships between faculty and students. • In keeping with the strong tradition of student involvement in all levels of Alpha Chi, the journal will also provide a forum for students to become actively involved in the writing, peer review, and publication process. • More information and instructions for authors is available under the publications tab at www.AlphaChiHonor.org. Questions to the editor may be directed to [email protected]. Alpha Chi is a national college honor society that admits students from all academic disciplines, with membership limited to the top 10 percent of an institution’s juniors, seniors, and graduate students. -

Summary of Sensory Team Manager Duties

Link to thesis website Chapter 6 Competing speech communities Chapter 6 Competing speech communities The final chapter of this section focuses on the evolution of folk tradition, and the new spaces created for performance, within the Celto-Cornish movement through the latter half of the twentieth century to the current era of festival culture and Pan- Celticism. It makes the case that the Celto-Cornish movement and the folk revival that arrived in Cornwall in the sixties represent different speech communities, which competed for ownership of oral folk tradition and the authenticity it represented. It must be also be recognised that there is a third speech community with a stake in the celebration of tradition, the local community within which it takes place. One outcome of these competing speech communities is the way in which the same folk phenomena will be used to express quite different identities. The Padstow May Day festivities for example are a celebration that firstly represents a sense of the towns community1 and secondly a Celto-Cornish tradition2 but at the same time is used as an icon by the English Folk Dance And Song Society.3 Underlying this discussion, however, must be the recognition that identity is chaotically unique for each individual and each group of individuals, all of which are at the centre of a “complex web of being”.4 In order to pursue this argument it is first necessary to revisit and examine more closely what is meant by a speech community and how this might affect performance and meaning within oral folk tradition. -

Britishness, What It Is and What It Could Be, Is

COUNTY, NATION, ETHNIC GROUP? THE SHAPING OF THE CORNISH IDENTITY Bernard Deacon If English regionalism is the dog that never barked then English regional history has in recent years been barely able to raise much more than a whimper.1 Regional history in Britain enjoyed its heyday between the late 1970s and late1990s but now looks increasingly threadbare when contrasted with the work of regional geographers. Like geographers, in earlier times regional historians busied themselves with two activities. First, they set out to describe social processes and structures at a regional level. The region, it was claimed, was the most convenient container for studying ‘patterns of historical development across large tracts of the English countryside’ and understanding the interconnections between social, economic, political, demographic and administrative history, enabling the researcher to transcend both the hyper-specialization of ‘national’ historical studies and the parochial and inward-looking gaze of English local history.2 Second, and occurring in parallel, was a search for the best boundaries within which to pursue this multi-disciplinary quest. Although he explicitly rejected the concept of region on the grounds that it was impossible comprehensively to define the term, in many ways the work of Charles Phythian-Adams was the culmination of this process of categorization. Phythian-Adams proposed a series of cultural provinces, supra-county entities based on watersheds and river basins, as broad containers for human activity in the early modern period. Within these, ‘local societies’ linked together communities or localities via networks of kinship and lineage. 3 But regions are not just convenient containers for academic analysis. -

Cornwall. [Kelly S

1 4:46 FAR CORNWALL. [KELLY S ·FARMERS-continued. Northey John, Hawks-ground, St. Cle- Olds James, Fore street, ~t. Just-in• Nicholls John Arthur, Tredennick, ther, Egloskerry R.S.O Penwith H..S.O Veryan, Grampound Road NortheyJohn,HigherPenwartha,Perran- Olds Peter, Trewellard, Pendeen R.S.O Nicholls John P. Great Grogarth, Cor- Zabuloe R.S.O Olds Wm. Bosavern, St. Just-in-Pen- nclly, Grampound Road Northey Richard, Polmenna, Liskeard with R.S.O Nicholls l\Irs. Mary Ann, Landithy, Northey Richard, Treboy, St. Clether, Olds William, Towans, Lelant R.S.O Madrcm, Penzance Egloskerry R.S.O Olds Wm. jun. Polpear, Lelant R.S.O Nicholls Mrs. N arcissa,Carne,St.Mewan, Nor they T. Laneast, Egloskerry R.S. 0 Oliver Chas. Rew, Lanli,·ery, Rod m in St. Austell Northey W.R.Watergt.Advent,Camelfrd Oliver Edwin, Trewarrick, St. Cleer, Nicholls Xathaniel, Goonhavern, Cal- Northey William, Harrowbridg-e, St. LiskearU. lestock R.S.O Xeot, Liskeard Oliver George, Creegbrawse, Chace- Nicholls R. Downs, St. Clement, Truro• Northey William, Harveys, Tyward- water, Scorrier R.S.O Nicholls R. Landithy, Madron,Penzance reath, Par Station R.~.O Oliver H. Tregranack, Sithney, Helston Nicholls R. Prislow, Budock, Falmouth Northcy Wm. Hy. (Rep. of the late) Oliver John, Chark mills & Creney, Nicholas R. Prospidnick,Sithney,Helston Trenant,Egloshaylc, WadcbridgcR.S. 0 Lanlivery, Bodmin Nicholls Richard, Lanarth, St. Anthony- N ott Mrs. Elizabeth J. Trelowth, St. Olivcr John, Creney, Lanlivery,Bodmin in-i\Iencage, Helston Mewan, St. .Austell Oliver John, Penmarth, Redruth Nicholls Rd. Hcssick, St. Buryan R.S.O Nott .Jliss Ellen, Coyte, St. -

ANCIENT STONES and SACRED SITES in CORNWALL ======Editor: Cheryl Straffon

MEYN MAMVRO - ANCIENT STONES AND SACRED SITES IN CORNWALL ======================================================== Editor: Cheryl Straffon INDEX - ISSUE 1,1986 to ISSUE 89, 2016 ******************************************************************************* Index compiled and maintained by Raymond Cox The Index is by issue and page number, e.g.15/23 = Issue No 15 page 23. Entries for the Isles of Scilly are listed under "Isles of Scilly". ............................................................................................................................................................... A Abbotsham - 73/14 Aboriginal Songlines (see Songlines) Adder's Beads - (see Milpreves) Alex Tor (Bodmin Moor) - 64/12 Alignments - 1/12; 2/7; 3/6; 4/5; 5/2; 6/7; 7/2; 8/4; 8/8-10; 9/4; 10/4; 10/7; 14/4; 20/4-5; 23/3; 23/24; 29/5; 31/3; 32/3; 34/8; 37/16; 47/11; 61/18; 63/18; 65/18; 66/14; 67/14-19; 68/10; 69/13; 70/8-10; 72/6; 73/13; 74/7; 77/6; 77/13; 77/16; 77/20; 78/3; 78/6; 78/7; 78/21; 79/2; 79/8; 80/12-24; 81/7; 81/9; 81/24; 82/6; 82/19; 83/6; 83/10; 84/6; 84/24; 85/6; 85/18; 86/6; 86/8; 86/14; 86/24; 87/16; 88/8; 89/6 Alignments map - 87/23; 88/21 Alignments map- 88 Supplement insert (Palden Jenkins) Allentide - 1/19 Alsia Mill - 74/6 Altar stones - 10/5 Anasazi - 14/21 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle - 8/20 Ancient Egyptian Centre - 59/24 Ancient tracks - 81/9; 82/6; 83/6; 84/6; 85/6; 86/6; 88/6 Ankh - (see Crosses, General) Animals (see Celtic totem animals) Anomalous phenomena - 4/3; 10/8; 11/19; 11/20; 12/19; 12/24; 14/3; 16/5; 17/2; 17/5; 18/5;