Fu-Tong Wong, a Taiwanese Violin Pedagogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-Born Chinese Amy Wong New York University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 13 2007 Article 17 Issue 2 Selected Papers from NWAV 35 10-1-2007 Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-born Chinese Amy Wong New York University This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol13/iss2/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-born Chinese This conference paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: http://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/ vol13/iss2/17 Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-Born Chinese in New York City* Amy Wong 1 Introduction Variationist sociolinguistics has largely overlooked the English of Chinese Americans, sometimes because many of them spoke English non-natively. However, the number of Chinese immigrants has grown over the last 40 years, in part as a consequence of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act that repealed the severe immigration restrictions established by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (García 1997). The 1965 act led to an increase in the number of America Born Chinese (ABC) who, as a result of being immersed in the American educational system that “urges inevitable shift to English” (Wong 1988:109), have grown up speaking English natively. Tsang and Wing even assert that “the English verbal performance of native-born Chinese Americans is no different from that of whites” (1985:12, cited in Wong 1988:210), an assertion that requires closer examination. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts 中華表演藝術基金會

中華表演藝術基金會 FOUNDATION FOR CHINESE PERFORMING ARTS [email protected] www.ChinesePerformingArts.net The Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts, is a non-profit organization registered in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in January, 1989. The main objectives of the Foundation are: * To enhance the understanding and the appreciation of Eastern heritage through music and performing arts. * To promote Chinese music and performing arts through performances. * To provide opportunities and assistance to young Asian artists. The Founder and the President is Dr. Catherine Tan Chan 譚嘉陵. AWARDS AND SCHOLARSHIPS The Foundation held its official opening ceremony on September 23, 1989, at the Rivers School in Weston. Professor Chou Wen-Chung of Columbia University lectured on the late Alexander Tcherepnin and his contribution in promoting Chinese music. The Tcherepnin Society, represented by the late Madame Ming Tcherepnin, an Honorable Board Member of the Foundation, donated to the Harvard Yenching Library a set of original musical manuscripts composed by Alexander Tcherepnin and his student, Chiang Wen-Yeh. Dr. Eugene Wu, Director of the Harvard Yenching Library, was there to receive the gift that includes the original orchestra score of the National Anthem of the Republic of China commissioned in 1937 to Alexander Tcherepnin by the Chinese government. The Foundation awarded Ms. Wha Kyung Byun as the outstanding music educator. In early December 1989, the Foundation, recognized Professor Sylvia Shue-Tee Lee for her contribution in educating young violinists. The recipients of the Foundation's artist scholarship award were: 1989 Jindong Cai 蔡金冬, MM conductor ,New England Conservatory, NEC (currently conductor and Associate Professor of Music, Stanford University,) 1990: (late) Pei-Kun Xi, MM, conductor, NEC; 1991: pianists John Park and J.G. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Friday, February 5, 2016, at 8:00 Saturday, February 6, 2016, at 8:00 Gennady Rozhdestvensky Conductor Music by Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 Allegretto—Allegro non troppo Allegro Lento—Largo—Lento Allegro molto—Lento INTERMISSION Symphony No. 15 in A Major, Op. 141 Allegretto Adagio Allegretto Adagio—Allegretto Saturday’s concert is sponsored by ITW. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Dmitri Shostakovich Born September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Died August 9, 1975, Moscow, Russia. Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 In our amazement at a keen ear, a sharp musical memory, and great those rare talents who discipline—all the essential tools (except, per- mature early and die haps, for self-confidence and political savvy) for a young—Mozart, major career in the music world. His Symphony Schubert, and no. 1 is the first indication of the direction his Mendelssohn immedi- career would take. Written as a graduation thesis ately come to mind—we at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, it brought often undervalue the less him international attention. In the years imme- spectacular accomplish- diately following its first performance in May ments of those who burst 1926, it made the rounds of the major orchestras, on the scene at a young age and go on to live beginning in this country with the Philadelphia long, full, musically rich lives. -

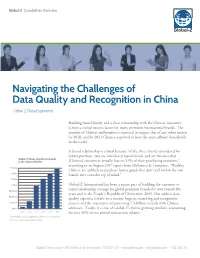

Navigating the Challenges of Data Quality and Recognition in China Global-Z China Experience

Global-Z Capabilities Overview Navigating the Challenges of Data Quality and Recognition in China Global-Z China Experience Building brand loyalty and a close relationship with the Chinese consumer is now a critical success factor for many premium international brands. The number of Chinese millionaires is expected to surpass that of any other nation by 2018, and by 2021 China is expected to have the most affluent households in the world. A brand relationship is critical because “of the three brands considered for luxury purchase, two are considered top-of-mind, and are the ones that Global-Z Shows Significant Growth in the Chinese Market (Chinese) consumers actually buy on 93% of their purchasing occasions,” according to an August 2017 report from McKinsey & Company. “Wealthy 7.5 Billion Chinese are unlikely to purchase luxury goods that don’t fall within the two 5 Billion brands they consider top of mind.” 2.5 Billion 1 Billion Global-Z International has been a major part of building the customer to 750 Million brand relationship strategy for global premium brands for over twenty-five years and in the People’s Republic of China since 2003. Our address data 500 Million quality expertise is built on a mature hygiene, matching and recognition 50 Million process and the experience of processing 7.5-billion records with Chinese 5 Million addresses. Today, it is one of Global-Z’s fastest growing markets, accounting 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 for over 50% of our annual transaction volume. Cumulative cleansing transactions processed on Chinese name and address data. -

The Taiwanese Violin System: Educating Beginners to Professionals

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2020 THE TAIWANESE VIOLIN SYSTEM: EDUCATING BEGINNERS TO PROFESSIONALS Yu-Ting Huang University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0469-9344 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.502 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Huang, Yu-Ting, "THE TAIWANESE VIOLIN SYSTEM: EDUCATING BEGINNERS TO PROFESSIONALS" (2020). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 172. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/172 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Hung-Kuan Chen, Piano Boswell Recital Hall

中華表演藝術基金會 Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts The 17th Annual Music Festival at Walnut Hill Concerts and Master Class August 1 - 22, 2008 Except the August 20’s Esplanade Concert, all the events will be held at the Walnut Hill School, 12 Highland St. Natick, MA 01760. ($5 donation at door) Tuesday, August 12, 2008, 7:30 PM Hung-Kuan Chen, Piano Boswell Recital Hall Program Brahms: Op. 116 no.4 Beethoven: Sonata No. 28, Op. 101 Brahms: Variations on a Theme of Paganini Bartok: Out of Doors Suite Rachmaninoff: Sonata Allegro Agitato Non Allegro Allegro Molto Professor Hung-Kuan Chen 陳宏寬, pianist “Back in the ‘80’s, Apollo and Dionysus, Florestan and Eusebius, were at war in Chen’s pianistic personality. He could play with poetic insight, he could also erupt into an almost terrifying overdrive. But now there is the repose and the forces have been brought into complimentary harmony. ....This man plays music with uncommon understanding and the instrument with uncommon imagination!” Richard Dyer, Boston Globe. (January 1999) Mr. Hung-Kuan Chen is probably the most decorated pianist in Boston. He won the Gold Medals both in Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition in Israel and the Feruccio Busoni International Piano Competitions in Italy. He gathered prizes in Geza Anda, the Queen Elisabeth and the Chopin competitions and when the New York Times failed to cover Chen’s Alice Tully debut, after winning Young Concert Artists, Ruth Laredo in another NY publication exclaimed, “rarely have I heard such eloquence and musical understanding. Is anyone listening?” A true recitalist, he has performed in major venues worldwide. -

FACULTY and GUEST ARTIST RECITAL Schubertiad KATHLEEN

FACULTY AND GUEST ARTIST RECITAL ”Schubertiad” KATHLEEN WINKLER, Violin JAMES DUNHAM, Viola BRINTON AVERIL SMITH, Cello BENJAMIN STOEHR, Cello (student) SAMI MYERSON, Cello (student) KRISTOPHER KHANG, Cello (guest) TIMOTHY PITTS, Double bass EVELYN CHEN, Piano (guest) Monday, October 27, 2014 8:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall PROGRAM Marcia in G Minor, D. 818 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Marche Militaire in D Major, D. 733 arranged Dešpalj deranged Smith Benjamin Stoehr, cello Sami Myerson, cello Kristopher Khang, cello Brinton Smith, cello Fantasie in F Minor, D. 940 arr. Kevin Dvorak Allegro molto moderato Largo Scherzo. Allegro vivace Finale. Allegro molto moderato Introduction, Theme and Variations, D. 603 arr. Piatigorsky Brinton Averil Smith, cello Evelyn Chen, piano PAUSE Quintet for Piano and Strings in A Major, D.667 “Trout” Allegro vivace Andante Scherzo: Presto Andantino – Allegretto Allegro giusto Kathleen Winkler, violin James Dunham, viola Brinton Smith, cello Timothy Pitts, double bass Evelyn Chen, piano The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHIES The New York Times hailed EVELYN CHEN as “a pianist to watch,” praising her “brilliant technique, warm, clear tone, and exacting musical intelligence.” Ms. Chen’s recent engagements have included performances on five continents at venues including Avery Fisher Hall and Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, Carnegie’s Weill Recital Hall, the Dorothy Chan- dler Pavilion, Wolf Trap, the Mozarteum in Salzburg, the National Concert Hall in Taipei, the Central Conservatory Concert Hall in Beijing, the Cul- tural Center of Hong Kong, and the Tchaikovsky Hall in Moscow. -

The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in TESL Department of English 12-2019 The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners Yahui Shi Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/tesl_etds Recommended Citation Shi, Yahui, "The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners" (2019). Culminating Projects in TESL. 17. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/tesl_etds/17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in TESL by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual learners by Yahui Shi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Thesis Committee: Choonkyong Kim, Chairperson John Madden Zengjun Peng 2 Abstract This study investigates Chinese vocabulary acquisition of Chinese language learners in English-Chinese bilingual contexts; the 20 participants in this study were English native speakers, who were enrolled in a Chinese immersion program in central Minnesota. The study used a matching test, and the test contains seven sets of test items. In each set, there were six Chinese vocabulary words and the English translations of three of them. The six words are listed in one column on the left, and the three translations were in another column on the right. -

Transfer of Perceptual Expertise: the Case of Simplified and Traditional Chinese Character Recognition

Cognitive Science (2016) 1–28 Copyright © 2016 Cognitive Science Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0364-0213 print / 1551-6709 online DOI: 10.1111/cogs.12307 Transfer of Perceptual Expertise: The Case of Simplified and Traditional Chinese Character Recognition Tianyin Liu,a Tin Yim Chuk,a Su-Ling Yeh,b Janet H. Hsiaoa aDepartment of Psychology, University of Hong Kong bDepartment of Psychology, National Taiwan University Received 10 June 2014; received in revised form 23 July 2015; accepted 3 August 2015 Abstract Expertise in Chinese character recognition is marked by reduced holistic processing (HP), which depends mainly on writing rather than reading experience. Here we show that, while simpli- fied and traditional Chinese readers demonstrated a similar level of HP when processing characters shared between the simplified and traditional scripts, simplified Chinese readers were less holistic than traditional Chinese readers in perceiving simplified characters; this effect depended mainly on their writing rather than reading performance. However, the two groups did not differ in HP of traditional characters, regardless of their difference in reading and writing performances. Our image analysis showed high visual similarity between the two character types, with a larger vari- ance among simplified characters; this may allow simplified Chinese readers to interpolate and generalize their skills to traditional characters. Thus, transfer of perceptual expertise may be con- strained by both the similarity in feature and the difference in exemplar variance between the cate- gories. Keywords: Holistic processing; Chinese character recognition; Reading; Writing 1. Introduction Holistic processing (i.e., gluing features together into a Gestalt) has been found to be a behavioral visual expertise marker for the recognition of faces (Tanaka & Farah, 1993) and many other nonface objects, such as cars (Gauthier, Curran, Curby, & Collins, 2003), fingerprints (Busey & Vanderkolk, 2005), and greebles (a kind of artificial stimuli; Gau- thier & Tarr, 1997). -

MATTER of WONG in Visa Petition Proceedings

Interim Decision #2165 MATTER OF WONG In Visa Petition Proceedings A-19168778 Decided by Board September 18, 1972. Since a visa petition involving a claimed adoptive relationship must be consid- ered from a factual point of view to determine if the claimed familial relationship is established, the instant visa petition to accord beneficiary fourth preference classification on the basis of her claimed adoption in Hong Kong in 1951 by the U.S. citizen petitioner's wife (allegedly unmarried at the time) is remanded to the District Director to make appropriate findings as to the factual validity of the adoption, with particular attention to the exploration of ques- tions raised by certain factual discrepancies relating to identity of the parties and the existence of the adoptive relationship, and to require the submission of supporting secondary evidence in the form of affidavits executed by petitioner and his wife, by witnesses to the adoption, and by relatives and neighbors. ON BEHALF OF PETITIONER: ON BEHALF OF SERVICE: Z. B. Jackson, Esquire R. A. Vielhaber 580 Washington Street Appellate Trial Attorney San Francisco, California 94111 (Brief filed) (Brief filed) The United States citizen petitioner applied for preference status for the beneficiary as his married adopted stepdaughter under section 203(a)(4) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. The District Director, in an order dated April 16, 1969, denied the application. From that order the petitioner appeals. The case will be remanded. The beneficiary is a female of Chinese ancestry who was born in Canton, China in 1948. She was purportedly adopted in Hong Kong in 1951 by Leung Wai Jun, at a time when Leung Wai Jun was not married. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

PITTSBURGH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WilliAM STEINBERG • Music Director HENRY MAZER • Associate Conductor THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 9th, 1967 at 8:30p.m. BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC 30 Lafayette Avenue 11217 Phone: ST. 3-2434 Seats: Orch: $6.00; Mezz (A-G): $6.00; (H-Q): $5.00 Bale: (A-E): $4.00; (F-K): $3.00 (L-M): $2.00 Boxes: $7.00; $6.00; $4.00; $3.00 Mail orders filled prompt:ly; send self-addressed st:amped envelope /967 ~ 0/?57 WILLIAM STEINBERG, Music Director Photo by Ben Spiegel Considered one of the six leading orchestras of the world, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is now in its forty-first year. Under Dr. Wi IIi am Steinberg's direction, the Orchestra boasts an annual audience of over 1,000,000 persons, in a city noted as well for its sports dedication and industrial prowess. Dr. Steinberg, currently in his 16th season as Music Director, is acclaimed for his inventive programs ranging from world premieres to the finest Qf the classics. The renown of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is wide-spread. There are annual tours to various parts of the United States, and in 1964, the Orchestra toured through Europe and the Middle East under the auspices of the U. S. State Department. By way of its superlative recordings for Command Classics, the Pittsburgh Symphony reaches the farthest corners of the musical world. THE CRITICS SPEAK: New York Times: " Dr. Steinberg and hi s musicians performed like the experts they are." Dallas Times Herald: "Close to the top in the whole world." Kansas City Times: "The finest orchestral program of the season." New Orleans States-Item: "This is a great orchestra." PITTSBURGH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 207 Rockwell-Standard Building, Pittsburgh, Pa.