Caribbean Cinema Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari Annika McPherson Abstract: While the male focus of early literary representations of Rastafari tends to emphasize the movement’s emergence, goals or specific religious practices, more recent depictions of Rasta women in narrative fiction raise important questions not only regarding the discussion of gender relations in Rastafari, but also regarding the functions of literary representations of the movement. This article outlines a dialogical ‘reasoning’ between the different negotiations of gender in novels with Rastafarian protagonists and suggests that the characters’ individual spiritual journeys are key to understanding these negotiations within the gender framework of Rastafarian decolonial practices. Male-centred Literary Representations of Rastafari Since the 1970s, especially, ‘roots’ reggae and ‘dub’ or performance poetry have frequently been discussed as to their relations to the Rastafari movement – not only based on their lyrical content, but often by reference to the artists or poets themselves. Compared to these genres, the representation of Rastafari in narrative fiction has received less attention to date. Furthermore, such references often appear to serve rather descriptive functions, e.g. as to the movement’s philosophy or linguistic practices. The early depiction of Rastafari in Roger Mais’s “morality play” Brother Man (1954), for example, has been noted for its favourable representation of the movement in comparison to the press coverage of -

Wavelength (April 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1981 Wavelength (April 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1981) 6 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL 1 981 VOLUME 1 NUMBE'J8. OLE MAN THE RIVER'S LAKE THEATRE APRIL New Orleans Mandeville, La. 6 7 8 9 10 11 T,HE THE THIRD PALACE SUCK'S DIMENSION SOUTH PAW SALOON ROCK N' ROLL Baton Rouge, La. Shreveport. La. New Orleans Lalaye"e, La. 13 14 15 16 17 18 THE OLE MAN SPECTRUM RIVER'S ThibOdaux, La. New Orleans 20 21 22 23 24 25 THE LAST CLUB THIRD HAMMOND PERFORMANCE SAINT DIMENSION SOCIAL CLUB OLE MAN CRt STOPHER'S Baton Rouge, La. Hammond, La. RIVER'S New Orleans New Orleans 27 29 30 1 2 WEST COAST TOUR BEGINS Barry Mendelson presents Features Whalls Success? __________________6 In Concert Jimmy Cliff ____________________., Kid Thomas 12 Deacon John 15 ~ Disc Wars 18 Fri. April 3 Jazz Fest Schedule ---------------~3 6 Pe~er, Paul Departments April "Mary 4 ....-~- ~ 2 Rock 5 Rhylhm & Blues ___________________ 7 Rare Records 8 ~~ 9 ~k~ 1 Las/ Page _ 8 Cover illustration by Rick Spain ......,, Polrick Berry. Edllor, Connie Atkinson. -

Classic Caribbean Stage & 2006 Screen Series

March Classic Caribbean Stage & 2006 Screen Series Trevor Rhone Festival :: Trevor Rhone - Film Fest :: Bellas Gate Boy - A Performance of a Lifetime :: When Writers Speak - Trevor Rhone, Collin Channer; Glenville Lovell :: Info & Tickets Greetings An expanded Classic Caribbean Stage and Screen Series pays homage to the groundbreaking work of Jamaican writer, producer, director, and actor Trevor D. Rhone. Best know in the United States for co- writing the internationally acclaimed film The Harder They Come, his 40+ year career in cultural arts has been the backbone of Jamaica’s indigenous film and theatre industry. To properly appreciate the facets of this multi- disciplinary writer, the series kicks off with a look at his film work, moves on to a session Caribbean writing for the ear and eye with acclaimed Caribbean-American writers Collin Channer and Glenville Lovell, and ends with Mr. Rhone performing in his witty yet poignant look at his life as county boy making good! Trevor Rhone - Film Fest Bellas Gate Boy - A Saturday, March Performance of a Lifetime 18, 2005 Wednesday, March 22, 2006 - 7pm Spike Lee Screening St. Johns University Room Marillac Auditorium Long Island 8000 Utopia Pkwy, Jamaica, NY University, Brooklyn Campus Trevor Rhone weaves a compelling, witty, and One University Plaza, poignant tale in this autobiographical account of his Brooklyn, NY (corner path from a rural community to the heights of fame Dekalb Ave & Flatbush Ave Ext) as the preeminent Jamaican dramatist of his generation. 12:30pm Opening “Beach Party” Reception – Sponsored St. John’s University Office of the Provost, the by Grace Kennedy Foods (USA) Multicultural Advisory Committee, Committee on Latin American and Caribbean Studies, and various 1:00pm Smile Orange (1974) student organizations host this community Written and Directed by: Trevor Rhone. -

Tourism and Place in Treasure Beach, Jamaica: Imagining Paradise and the Alternative. Michael J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 Tourism and Place in Treasure Beach, Jamaica: Imagining Paradise and the Alternative. Michael J. Hawkins Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Hawkins, Michael J., "Tourism and Place in Treasure Beach, Jamaica: Imagining Paradise and the Alternative." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7044. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7044 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bteedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

From the Harder They Come to Yardie the Reggae-Ghetto Aesthetics of the Jamaican Urban Crime Film Martens, E

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) From The Harder They Come to Yardie The Reggae-Ghetto Aesthetics of the Jamaican Urban Crime Film Martens, E. DOI 10.1080/1369801X.2019.1659160 Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Published in Interventions : International Journal of Postcolonial Studies License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Martens, E. (2020). From The Harder They Come to Yardie: The Reggae-Ghetto Aesthetics of the Jamaican Urban Crime Film. Interventions : International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 20(1), 71-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2019.1659160 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 FROM THE HARDER THEY COME TO YARDIE The Reggae-Ghetto Aesthetics of the Jamaican Urban Crime Film Emiel Martensa,b aDepartment of Arts and Culture Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands; bDepartment of Media Studies, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands ................. -

Narco-Narratives and Transnational Form: the Geopolitics of Citation in the Circum-Caribbean

Narco-narratives and Transnational Form: The Geopolitics of Citation in the Circum-Caribbean Jason Frydman [email protected] Brooklyn College Abstract: This essay argues that narco-narratives--in film, television, literature, and music-- depend on structures of narrative doubles to map the racialized and spatialized construction of illegality and distribution of death in the circum-Caribbean narco-economy. Narco-narratives stage their own haunting by other geographies, other social classes, other media; these hauntings refract the asymmetries of geo-political and socio-cultural power undergirding both the transnational drug trade and its artistic representation. The circum-Caribbean cartography offers both a corrective to nation- or language-based approaches to narco-culture, as well as a vantage point on the recursive practices of citation that are constitutive of transnational narco-narrative production. A transnational field of narrative production responding to the violence of the transnational drug trade has emerged that encompasses music and film, television and journalism, pulp and literary fiction. Cutting across nations, languages, genres, and media, a dizzying narrative traffic in plotlines, character-types, images, rhythms, soundtracks, expressions, and gestures travels global media channels through appropriations, repetitions, allusions, shoutouts, ripoffs, and homages. While narco-cultural production extends around the world, this essay focuses on the transnational frame of the circum-Caribbean as a zone of particularly dense, if not foundational, narrative traffic. The circum-Caribbean cartography offers 2 both a corrective to nation- or language-based approaches to narco-culture, as well as a vantage point on incredibly recursive practices of citation that are constitutive of the whole array of narco-narrative production: textual, visual, and sonic. -

Community, Family and Youth Resilience (CFYR) Program Annual Report October 1, 2018 to September 30, 2019

Community, Family and Youth Resilience (CFYR) Program Annual Report October 1, 2018 to September 30, 2019 Submission Date: October 30, 2019. Updated December 18, 2019. Submitted by: Creative Associates International 1 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AAA - Action and Advocacy Agenda BLES - Basic Life and Employability Skills CARICOM – Caribbean Community CSWC - Charlotte Street Wesleyan Church COP - Chief of Party CEC - Community Enhancement Committees CFYR - Community, Family and Youth Resilience Program CSP - Community Safety Plan CLC - Critchlow Labour College DQA - Data Quality Assessment DCOP – Deputy Chief of Party DPP - Director of Public Prosecution FACES - Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scales FACT - Family Awareness Consciousness Togetherness FGD – Focus Group Discussion FYCW - Family and Youth Community Worker JJR – Juvenile Justice Reform LOP - life of program MoCD - Ministry of Community Development, Gender Affairs and Social Services (St. Kitts) MoE - Ministry of Equity, Social Justice, Empowerment and Local Government (Saint Lucia) MoPT - Ministry of Public Telecommunications (Guyana) MoSP - Ministry of Social Protection (Guyana) NOC – New Opportunity Corps NIA - Nevis Island Administration PIFSM - Prevention and Intervention Family Systems Model RLE - Regional Learning Exchange 2 RLN - Regional Learning Network RLIC - Ruimveldt Life Improvement Centre SCP - Social Crime Prevention SDCP - Social Development and Crime Prevention SLHTA - Saint Lucia Hospitality & Tourism Association SLS - Social and Leadership Skills SSDF - Saint -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Economic Development in Puerto Rico Faces Unprecedented Challenges

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Economic Development in Puerto Rico faces unprecedented challenges ECONOMIC CONTRACTION IRMA & MARIA HURRICANES The economy of Puerto Rico has been The magnitude of the devastation on the contracting for more than a decade. It has Island caused by the hurricanes Irma and a debt that exceeds 100 percent of its María is historic and demands an annual economic output and has caused extraordinary response for Puerto Rico to get fiscal liquidity and solvency challenges. back on its feet. PROMESA FEDERAL TAX REFORM The approval of PROMESA in 2016 has The federal tax reform (Tax Cuts & Jobs Act) created a certain lack of clarity regarding will have an impact, both on our current governance matters, which in turn may manufacturing base, and on the promotion impact our business climate. Uncertainty is strategies and incentives use to attract not good for local or external investors. foreign investment to the island. EVOLUTION OF PUERTO RICO’s ECONOMY IN THE PAST 70 YEARS ADVANCE MANUFACTURING, KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY, AGRARIAN ECONOMY INDUSTRIAL ECONOMY SERVICES Sugar cane, tobacco & coffee Petro-chemical, electronics, Life Sciences, Aerospace, Technology, apparel & textiles, Agro Tech Industries, Export Services, pharmaceuticals Tourism/Visitor’s Economy < 1950’s 1950-1990’s > 2000’s O U R E C O N O M Y TODAY GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT SHARE BY MAIN ECONOMIC SECTOR GPN $70.1 billion FISCAL YEAR 2017 GDP $105.0 billion Construction & Mining GDP PER CAPITA $30,516 0.9 Utilities 2.1 0.8 Agriculture EXPORTS VALUE $71.9 billion Government IMPORTS -

Understanding the Urgent Need for Subtitling for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in the Spanish-Speaking Greater Antilles

Understanding the Urgent Need for Subtitling for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in the Spanish-Speaking Greater Antilles Adrián Fuentes-Luque Universidad Pablo de Olavide Pabsi Livmar González-Irizarry Universidad Pablo de Olavide _________________________________________________________ Abstract Citation: Fuentes-Luque, A. & González- Even though audiovisual translation (AVT) is growing and flourishing Irizarry, P.L.. (2020). Understanding the throughout the world, it is practically unheard-of in the Caribbean, Urgent Need for Subtitling for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in the Spanish- where accessibility faces an even bleaker existence. The circumstances Speaking Greater Antilles. Journal of of the deaf and hard of hearing (also referred to as D/deaf) are no less Audiovisual Translation, 3(2), 286–309. alarming: social barriers and exclusion are widespread. This paper Editor(s): A. Matamala & J. Pedersen emphasizes the need to make subtitles accessible in the Spanish- Received: February 1, 2020 speaking Caribbean, specifically on the islands of Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Accepted: July 22, 2020 the Dominican Republic, and underscores the challenges faced by the Published: December 21, 2020 D/deaf communities on each island. Our research focuses on issues like Copyright: ©2020 Fuentes-Luque & AVT laws and regulations, the habits of viewers of audiovisual (AV) González-Irizarry. This is an open access products, and literacy and limitations on each island. This paper also article distributed under the terms of the examines the different types of D/deaf audiovisual consumers in the Creative Commons Attribution License. This allows for unrestricted use, Spanish-speaking Caribbean and the difficulties each community faces distribution, and reproduction in any when accessing media and entertainment. -

DIRECTORY a GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY It Is with Great Pleasure I Welcome You to the 2013 ICSC Caribbean Conference Being Held in San Juan, Puerto Rico

DIRECTORY A GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY It is with great pleasure I welcome you to the 2013 ICSC Caribbean Conference being held in San Juan, Puerto Rico. We come from a fantastic region, unique in the world. We are united by a common history, a vibrant present and a bright and promising future. From the Gulf of Mexico, through Central America to the northern area of South America; continuing on our journey, the region is interlaced with heavenly islands which, like pearls emanating from the sea, make up an extraordinary gem, famous in the world for its wealth in cultural diversity. This is Puerto Rico, this is the Caribbean Conference, where there is no other conference like it. Where we are going to feel at home and have the golden opportunity to meet with industry professionals of the most important shopping centers in this region, to network, share experiences, projects and visualize together our future. We look forward to another successful conference this year with great speakers and informative sessions. I hope that you also take advantage of meeting, networking and doing deals with this year’s exhibitors at the Trade Exhibition. I am excited that you can join us and hope to meet you during the conference. Alfredo Cohen ICSC Trustee, 2013 Caribbean Conference Program Planning Committee Chair Director Constructora Sambil Caracas, Venezuela GOLD SPONSORS SILVER SPONSOR BRONZE SPONSOR February 4–6, 2013 • Puerto Rico Convention Center • San Juan, Puerto Rico government finances. Now, signs of revival in economic activity MONday, FEBRuary 4, 2013 in the Caribbean are emerging. Nevertheless, while the recovery continues to move forward, growth globally is moving to a 8:00 am – 7:00 pm weaker, rather than a stronger, performance profile, thereby limiting Caribbean longer-term economic prospects. -

Part I - Updated Estimate Of

Part I - Updated Estimate of Fair Market Value of the S.S. Keewatin in September 2018 05 October 2018 Part I INDEX PART I S.S. KEEWATIN – ESTIMATE OF FAIR MARKET VALUE SEPTEMBER 2018 SCHEDULE A – UPDATED MUSEUM SHIPS SCHEDULE B – UPDATED COMPASS MARITIME SERVICES DESKTOP VALUATION CERTIFICATE SCHEDULE C – UPDATED VALUATION REPORT ON MACHINERY, EQUIPMENT AND RELATED ASSETS SCHEDULE D – LETTER FROM BELLEHOLME MANAGEMENT INC. PART II S.S. KEEWATIN – ESTIMATE OF FAIR MARKET VALUE NOVEMBER 2017 SCHEDULE 1 – SHIPS LAUNCHED IN 1907 SCHEDULE 2 – MUSEUM SHIPS APPENDIX 1 – JUSTIFICATION FOR OUTSTANDING SIGNIFICANCE & NATIONAL IMPORTANCE OF S.S. KEEWATIN 1907 APPENDIX 2 – THE NORTH AMERICAN MARINE, INC. REPORT OF INSPECTION APPENDIX 3 – COMPASS MARITIME SERVICES INDEPENDENT VALUATION REPORT APPENDIX 4 – CULTURAL PERSONAL PROPERTY VALUATION REPORT APPENDIX 5 – BELLEHOME MANAGEMENT INC. 5 October 2018 The RJ and Diane Peterson Keewatin Foundation 311 Talbot Street PO Box 189 Port McNicoll, ON L0K 1R0 Ladies & Gentlemen We are pleased to enclose an Updated Valuation Report, setting out, at September 2018, our Estimate of Fair Market Value of the Museum Ship S.S. Keewatin, which its owner, Skyline (Port McNicoll) Development Inc., intends to donate to the RJ and Diane Peterson Keewatin Foundation (the “Foundation”). It is prepared to accompany an application by the Foundation for the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board. This Updated Valuation Report, for the reasons set out in it, estimates the Fair Market Value of a proposed donation of the S.S. Keewatin to the Foundation at FORTY-EIGHT MILLION FOUR HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-FIVE THOUSAND DOLLARS ($48,475,000) and the effective date is the date of this Report. -

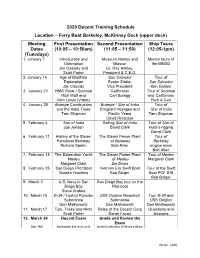

2020 Docent Training Schedule Location – Ferry Boat Berkeley

2020 Docent Training Schedule Location – Ferry Boat Berkeley, McKinney Deck (upper deck) Meeting First Presentation Second Presentation Ship Tours Dates (10:05 – 10:50am) (11:05 – 11:50) (12:05-1pm) (Tuesdays) 1. January 7 Introduction and Museum History and Mentor tours of Orientation Mission the MMSD Jim Cassidy and Dr. Ray Ashley, Scott Porter President & C.E.O. 2. January 14 Age of Maritime San Salvador Tour of Exploration Susan Sirota, San Salvador Jim Cassidy Vice President Ken Golden 3. January 21 HMS Rose / Surprise Californian Tour of Surprise Rich Wolf and Carl Scragg and Californian Kelli Lewis (Video) Rich & Carl 4. January 28 Euterpe Construction Euterpe / Star of India Tour of and the India Trade Emigrant Voyages and Star of India Tom Shipman Pacific Years Tom Shipman David Ringrose 5. February 4 Star of India Sailing Star of India Tour of Star of Joe Jenson David Clark India’s rigging David Clark 6. February 11 History of the Steam The Steam Power Plant Tour of Ferryboat Berkeley of Berkeley Berkeley Richard Spehn Bob Allan engine room Bob Allan 7. February 18 The Edwardian Yacht The Steam Power Plant Tour of Medea Medea of Medea Margaret Clark Margaret Clark Jim Davis 8. February 25 San Diego Pilot Boat Vietnam Era Swift Boat Tour of the Swift Gurden Hutchins Bob Bolger Boat PCF 816 Bob Bolger 9. March 3 U.S. Navy in San San Diego Bay tour on the Diego Bay Pilot boat Steve Andres 10. March 10 B-39 / Foxtrot Russian USS Dolphin Research Tour B-39 and Submarine Submarine USS Dolphin Don Mathiowetz Don Mathiowetz Don Mathiowetz 11.