Oral History Interview with Michael James, 2003 January 4-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Spring 2003 Newsletter

Nel5iasKa Lincoln NEWSLETTER Spring 2 0 0 3 From the Interim Director --Susan Belasco literature, and the workplace. Many of our students and faculty participated in the annual No Limits Conference Serving as the interim director of Women's held this year at UNO. Plans are well underway for No Studies during this semester has been a delightful Limits 2004, which will be held here at UNL and which experience for me-the chance to participate much will feature the experimental documentary filmmaker, more fully in the many activities of our program, get Lourdes Portillo, one of Ms. Magazine's Women of the to know our wonderful and dedicated staff, meet Year for 2002. current and prospective students, and observe first Thanks to the efforts of Joy and our staff, hand the impressive leadership of our director, Joy Women's Studies now has a reading room, adjacent to the Ritchie, who is on Faculty Development Leave this offices in 1214 Oldfather. The Women's Studies reading spring. room and offices (which already feature the artwork of The semester has been a busy one in staff member Glenda Moore) are filled with the artworks Women's Studies. Our Women's Studies of The Nebraska Women's Caucus for Art. The show, Colloquium series included "What Do You Do with "Storefront Window Dressing: Women Dressed/Women a Women's Studies Major?" featuring Kris Gandara, Addressed," opened on March 7 with a reception in the Gretchen Obrist, Cheri sa Price-Wells, Keri Wayne, Women's Studies offices. Rachel West, and moderated by Professor Elizabeth My term as Director ends in May, and I will Suter in Communications Studies. -

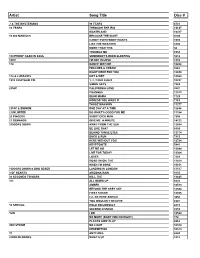

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference

SUMMER 2020 HAYSTACK MOUNTAIN SCHOOL OF CRAFTS Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference Schedule at a Glance 4 SUMMER 2020 Life at Haystack 6 Open Studio Residency 8 Session One 10 Welcome Session Two This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the 14 Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. The decision to start a school is a radical idea in and Session Three 18 of itself, and is also an act of profound generosity, which hinges on the belief that there exists something Session Four 22 so important it needs to be shared with others. When Haystack was founded in 1950, it was truly an experiment in education and community, with no News & Updates 26 permanent faculty or full-time students, a school that awarded no certificates or degrees. And while the school has grown in ways that could never have been Session Five 28 imagined, the core of our work and the ideas we adhere to have stayed very much the same. Session Six 32 You will notice that our long-running summer conference will take a pause this season, but please know that it will return again in 2021. In lieu of a Summer Workshop 36 public conference, this time will be used to hold Information a symposium for the Haystack board and staff, focusing on equity and racial justice. We believe this is vital Summer Workshop work for us to be involved with and hope it can help 39 make us a more inclusive organization while Application broadening access to the field. As we have looked back to the founding years of the Fellowships 41 school, together we are writing the next chapter in & Scholarships Haystack’s history. -

Stjohn-Catholic.Org Fifth Sunday of Lent April 2, 2017 Ninth & Boulevard, P.O. Box 510 Edmond, OK 73083-0510, 405-340-0

stjohn-catholic.org Fifth Sunday of Lent April 2, 2017 MASS TIMES As our season of Lent quickly draws to a close, we are reminded today Saturday Vigil, 5:30 pm* that God's creative and life giving Sunday 7:30 am, 9:00 am*, presence is always at work, bringing 11:30 am*, light out of darkness and new life 5:30 pm* out of death. The prophet Ezekiel Daily & See “Masses For reminds us that God's spirit is within Holy Days The Week” us. Realizing this allows us to endure not only our eventual physical *NURSERY AVAILABLE deaths but any difficulty, disappoint- SACRAMENT SCHEDULE ment or crisis we may encounter. PENANCE Saturday 4:00-5:00 pm St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic School Wednesday 5:00-6:00 pm OPEN HOUSE BAPTISM PREP CLASS ~Readings ~ Contact Dr. Harry Kocurek TODAY, April 2, 2017 Week of April 2, 2017 MATRIMONY Come by anytime between 1:00—3:00 pm Contact priest at least six Sun. Fifth Sunday of Lent We look forward to showing you around. months in advance Ez 37:12-14; Ps 130:1-2, 3-4, 5-6, More information on page 10 or online ANOINTING OF THE SICK 7-8; Rom 8:8-11; Jn 11:1-45 or stelizabethedmond.org First Friday 7:30 am & 5:30 pm 11:3-7, 17, 20-27, 33b-45 Mon. Dn 13:1-9, 15-17, 19-30, 33-62 or PARISH STAFF Music Director CATHOLIC SCHOOL 13:41c-62; Ps 23:1-3a, 3b-4, 5, 6; Office 405-340-0691 Barbara Meiser x117 405-348-5364 • Fax 340-9627 Jn 8:1-11 Fax 405-340-5715 Accountants Principal, Laura Gallagher x137 Tues. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

International 300N.Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Ml 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pagc(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they arc spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning" the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Asma Mohseni, Summer Larson, and Ama Wertz!

SEPTEMBER 2014 NEWSLETTER PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE WHAT’S INSIDE? elcome to our members who joined us recently: Asma Mohseni, WSummer Larson, and Ama Wertz! Please find details to our next th meeting on September 20 in Berkeley in the pages of this newsletter! Our PAGE meeting will be at the home of Master Weaver Jean Pierre Larochette and 1 President’s Message Tapestry Designer and Weaver Yael Larochette’s home for a presentation 2 Next Meeting 3 Reminders on the release of their new book, “The Tree of Lives: Adventures Between 4 Water Water! Warp and Weft.” Thank you to our gracious hosts, Jean Pierre and Yael. 6 Unbroken Web 8 What Happened at THAT Meeting? Hopefully many of you in the area were able to make it to our EBMUD 10 Tapestry Redux Water, Water exhibition this summer. Many thanks to our hard working 12 Member News show committee Alex Friedman, Tricia Goldberg, and Sara Ruddy for 14 Business Info Your TWW Board Members handling all the moving parts, and putting on a wonderful and well attended Membership Dues opening reception! And also a great big thank you to our juror and co- Newsletter Submission Info founding TWW member Joyce Hulbert for curating our work into a lovely exhibition and writing a touching and tasteful text to accompany it. Please Tapestry Weavers West is an organization find Joyce’s words on our show in the pages of this newsletter. with a goal to act as a supporting educational and networking group for tapestry artists. For further details of membership information We will have some business to attend to after Jean Pierre and Yael’s please contact: presentation. -

![Oral History Interview with Kay Sekimachi [Stocksdale], 2001 July 26-August 6](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4108/oral-history-interview-with-kay-sekimachi-stocksdale-2001-july-26-august-6-1364108.webp)

Oral History Interview with Kay Sekimachi [Stocksdale], 2001 July 26-August 6

Oral history interview with Kay Sekimachi [Stocksdale], 2001 July 26-August 6 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project For Craft and Decorative Arts in America The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Kay Sekimachi on July 26 and 30, and August 3 and 6, 2001. The interview took place in Berkeley, California, and was conducted by Suzanne Baizerman for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Kay Sekimachi and Suzanne Baizerman have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MS. SUZANNE BAIZERMAN: This is Suzanne Baizerman interviewing Kay Sekimachi at the artist's home in Berkeley, California, on July 26, 2001. We're going to start today with some questions about Kay's background. So Kay, where were you born, and when was that? MS. KAY SEKIMACHI: I was born in San Francisco in 1926. My parents were first generation Japanese Americans; that is, my father [Takao Sekimachi] never got naturalized, but my mother [Wakuri Sekimachi] did become a naturalized citizen. -

Textiles in Contemporary Art, November 8, 2005-February 5, 2006

Term Limits: Textiles in Contemporary Art, November 8, 2005-February 5, 2006 Early in the twentieth century, artists of many nationalities began to explore the textile arts, questioning and expanding the definition of art to include fabrics for apparel and furnishings as well as unique textile works for the wall. Their work helped blur, for a time, distinctions among the fields of fine art, craft, and design. By the 1950s and 1960s artists working in fiber, influenced both by their studies in ancient textile techniques and by twentieth-century art theory, began to construct sculptural forms in addition to the more conventional two-dimensional planes. The term Fiber Art was coined in the 1960s to classify the work of artists who chose fiber media or used textile structures and techniques. It was joined in the 1970s by Wearable Art, applied to work that moved Fiber Art into the participatory realm of fashion. These labels did not only define and introduce these movements, they also set them apart, outside the mainstream. Some critics, focusing solely on medium and process, and disregarding conceptual values, associated work in fiber automatically with the terms craft and design, a distinction that renewed old and often arbitrary hierarchieswithin the art community. Although categorization sometimes provides valid context, it is important to remember that any given term has a limited capacity to encompass and explain an object, an idea, or a movement. At the same time, it limits one's ability to perceive creative endeavors without the shadow of another's point of view. The boundaries implied by terminology can marginalize or even exclude artists whose work blurs the traditional lines separating art, artisanry, and industry.