Arms and Armour Collections in and Around London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

There and Back Again: Mobilising Tourist Imaginaries at the Tower Of

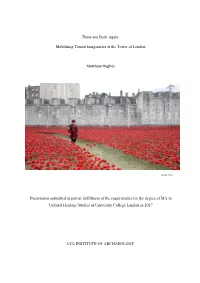

There and Back Again: Mobilising Tourist Imaginaries at the Tower of London Matthew Hughes Ansell 2014 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Cultural Heritage Studies of University College London in 2017 UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ‘Those responsible for the brochure had darkly intuited how easily their readers might be turned into prey by photographs whose power insulted the intelligence and contravened any notions of free will: over-exposed photographs of palm trees, clear skies, and white beaches. Readers who would have been capable of skepticism and prudence in other areas of their lives reverted in contact with these elements to a primordial innocence and optimism. The longing provoked by the brochure was an example, at once touching and bathetic, of how projects (and even whole lies) might be influenced by the simplest and most unexamined images of happiness; of how a lengthy and ruinously expensive journey might be set into motion by nothing more than the sight of a photograph of a palm tree gently inclining in a tropical breeze’ (de Botton 2002, 9). 2 Abstract Tourist sites are amalgams of competing and complimentary narratives that dialectically circulate and imbue places with meaning. Widely held tourism narratives, known as tourist imaginaries, are manifestations of ‘shared mental life’ (Leite 2014, 268) by tourists, would-be tourists, and not-yet tourists prior to, during, and after the tourism experience. This dissertation investigates those specific pre-tour understandings that inform tourists’ expectations and understandings of place prior to visiting. Looking specifically at the Tower of London, I employ content and discourse analysis alongside ethnographic field methods to identify the predominant tourist imaginaries of the Tower of London, trace their circulation and reproduction, and ultimately discuss their impact on visitor experience at the Tower. -

XXX. Notices of the Tower of London Temp. Elizabeth, and the Morse Armoury Temp

XXX. Notices of the Tower of London temp. Elizabeth, and the Morse Armoury temp. Charles I. In a Letter addressed byWu. DTJRRANT COOPER, Esq., F.S.A. to Robert Lemon, Esq., F.8.A. Read February 18, 1858. 81, Guilford Street, Russell Square, London, MY DEAR SIR, 15th February, 1858. THE facilities which you have afforded hy the publication of your Kalendar for the puhlic use of the valuable documents preserved in the State-Paper Office, relating to the first half of Queen Elizabeth's reign, and your kindness in per- mitting me to make extracts from your own book of MSS. on ancient armour, consisting of the scattered Exchequer documents, enable me to send to our Society some notices of the Tower of London and of the armouries there and at Green- wich, which are very interesting in themselves, and are chiefly of a date forty years earlier than the lists communicated by William Bray, Esq. P.S.A. to our Society, and reprinted by Meyrick from the Archseologia.a It was only after Elizabeth's public entry into London from Hatfield and the Charter House, on her accession in Nov. 1558, and her return from Westminster to the Tower on 12th January following, preparatory to her procession to West- minster on the 14th, the day before her coronation, that the Tower of London was used as a royal residence in her reign. It was, however, during all her reign the chief arsenal, the principal depdt for the ordnance and armoury, the depository for the jewels and treasures, the site of the Mint, the place where the public records were preserved, and the most important state prison. -

Teacher's Pack Tudor Cirencester LEARNING FOR

Teacher’s Pack Tudor Cirencester LEARNING FOR ALL Contents 1. Visiting the Museum Essential information about your visit 2. Health and Safety Information 3. Active Learning Session Information about the session booked 4. Pre-visit information Background information 5. Museum Floor Plan 6. Discovery Sheets Activity sheets for use in the galleries (to copy) 7. Evaluation Form What did you think of your visit? Visiting the Corinium Museum SUMMARY • Check , sign and send back the booking form as confirmation of your visit • Photocopy worksheets and bring clipboards and pencils on your visit • Arrive 10 minutes before your session to allow for toilet stop, payment and coats to be hung up • Assemble outside the Lifelong Learning Centre at your allocated session time • Remember pocket money or goody bag orders (if required) for the shop • After your visit please complete an evaluation form Visiting the Corinium Museum IN DEPTH Before your visit You will have arranged a time and booked an active learning session that you feel is most appropriate for your pupils. Check the confirmed time is as expected. Arrange adequate adult support. One adult per 10 children has free admittance but many classes benefit from extra help, especially during the active learning session which will require some adult supervision. The museum is a popular resource for schools and visitors of all ages and our aim is to provide an enjoyable and educational experience so please read our guidance to make the visit as enjoyable as possible. When you arrive Please arrange to arrive 10-15 minutes before your active learning session time. -

The Tower of London Were Written for the ” Daily Telegraph , and They Are Reprinted with the Kin D Permission of Its Proprietors

T H E T O W E R O F L O N D O N BY WALTE R G E OR G E BE LL W I T H E L E V E N D R A W I N G S BY H A N S L I P F L E T C H E R JOH N LANE TH E BODLEY HE AD NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY MCM! ! I C ONTENTS PAGE THE NORMAN KEEP ' THE TRAITORS GATE ' S L PETE R AD V I NCULA BLOODY TOWER AND RE GAL IA THE BEAUCHAM P TOWER ’ THE KI NG S H OUS E ’ S P T. JOHN S CHA EL ENTRANCE TOWERS I LLUSTR ATIONS A RI V ERSIDE GLI M PSE TOWER OF LONDON F ROM THE RIV ER TH E CON! UEROR’S KEEP TH E TRAITORS’ GATE TH E F W LL W CUR E , OR BE , TO ER ST. PETER AD VI NC ULA CHAPEL BLOODY TOWER AND WA KEF IELD TOWER BEAUC HAM P TOWER F RO M AC ROSS THE MOAT ’ TOWER GREEN AND THE KI NG S HOUSE N ’S A L WI I N ST. JOH CH PE TH THE KEEP MIDDLE TOWER AND BYWARD TOWER TH E TOWER PHOTOGRA PHED F ROM AN AEROPLANE I N TH E TE! T PLAN OF THE TOWER STRONG ROOM I N THE BELL TOWER JACOBITE LORDS’ STONE TH E DUDLEY REBUS ! UEEN JANE INSCRI PTION PR E FAC E HESE chapters upon the Tower of London were written for The ” Daily Telegraph , and they are reprinted with the kin d permission of its proprietors . -

Letter, Hubert Schneider To

The original documents are located in Box C41, folder “Presidential Handwriting, 5/28/1976” of the Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. !XHE PRES IDE:i:T HAS SEEN· • •"7 . ' May 28, 1975 Dear Yeoman Ford: The Beefeater Dinner in the Tower of London last week was great. Too bad you couldn't have been with us. Your friend Yeoman Hastings was present and sends his regards. Best wishes, /~ ~~0 ~/ 1;/A' / HUBERT A. SCHNEIDER Digitized from Box C41 of The Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library .. c. .. , ' ~ the:B~'IER CLUJ; oftbe I~tU\PORl\1__ E_D ~CIENT 0}\Q~ of1ht BEEFEK-rE~R. ~ PINING-fW.l thel\OYAL ~T cf F'USIUEJ\$ REGI1v\EN'lro HFADQUJ\RTERS H. .tt. TOWE\_'f LONDON © 1975 by The Beefeater Club (tO~OJt (fQ~OJt ~C.f\orf ~C.f\orf CHIEF~EL CHIEF~EL Whst~I.~nl Whitne_!i I.~nl ~ EJwarot J¥_k.n- Bml<;; UPPER.WAR.PER EMERI'l15 ~~13nms ~~~ lJPPEJtW\RPf!1t 1.\gNTEJ{~ Ei\STERN WUWfCK JOhn-T.~ Can-dt 1"\.Bowman UPPER W\RDER EXERJ.WS Th~~if H.Milm,. -

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries 149 Sir Charles

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES 149 Thursday, i$th January 1953. Sir James Mann, President, in the Chair. The following were elected Fellows of the Society: Dr. C. H. Talbot, Rev. Dom A. Hughes, Mr. H. Duff, Miss J. M. Reynolds, Prof. F. E. Zeuner, Miss M. G. Wilson, Mr. E. H. L. Sexton, Mr. F. B. Gilhespy, Mr. T. A. Lloyd, Mr. N. Walker, Dr. K. P. Oakley, Mr. A. H. Smith. The Birdlip Mirror was exhibited by the Secretary by permission of the Gloucester Museum. Mr. R. F. Jessup, F.S.A., exhibited MS. 723, the notes and correspondence of Rev. Bryan Faussett (F.S.A. 1763-76). Mr. E. M. Jope, F.S. A., exhibited late Saxon pottery from his excavations beneath the Oxford Castle mound. Dr. W. L. Hildburgh, F.S.A., exhibited a bronze vessel from the Middle East. Thursday, iind January 1953. Dr. E. G. Millar, Vice-President, in the Chair. Mr. and Mrs. Leslie Alcock read a paper on Bhambhor: an Arab port in Sind. Thursday, 29th January 1953. Sir James Mann, President, in the Chair. Miss Marion Wilson was admitted a Fellow. Professor Stuart Piggott, F.S.A., and Mr. R. J. C. Atkinson, F.S.A., read a paper on the Early Iron Age horse-mask from Torrs: a critical analysis. SIR CHARLES REED PEERS CHARLES REED PEERS, Knight, C.B.E., F.B.A., F.R.I.B.A., Litt.D., D.Lit., D.C.L., M.A., filled in suc- cession the offices of Secretary (1908-21), Director (1921—9), and President (1929—34) of this Society. -

Beefeaters, British History and the Empire in Asia and Australasia Since 1826

University of Huddersfield Repository Ward, Paul Beefeaters, British History and the Empire in Asia and Australasia since 1826 Original Citation Ward, Paul (2012) Beefeaters, British History and the Empire in Asia and Australasia since 1826. Britain and the World, 5 (2). pp. 240-258. ISSN 2043-8575 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/14010/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Beefeaters, British history and the Empire in Asia and Australasia since 1826 Paul Ward, Academy for British and Irish Studies, University of Huddersfield, UK A revised version of this article is published in Britain and the World. Volume 5, Page 240-258 DOI 10.3366/brw.2012.0056, ISSN 2043-8567 Abstract The Yeoman Warders at the Tower of London (colloquially known as ‘Beefeaters’) have been represented as a quintessential part of British history. -

Download Guide

A cheat sheet for newbies who want to begin their London adventure in full swing Joining our Kingdom in London? 1 For those that go the extra mile We know moving to another country is a life changing decision. That’s why we’ve gathered everything essential in this easy-to-read guide for you, so you don’t have to. This way you can enjoy your time fully when you get there – like digging into a proper fish & chips at the local pub after a game of football, watching EastEnders or hunting for that blue door in Notting Hill. Yes, there are lots of things to do in London, and we want to be there for you! Whether you’d like help finding the right visa or need inspiration for places to eat, live and sleep – King is at hand. 2 Contents A place for everyone and anyone 5 Quintessential London? 7 Out and about 8 Getting around 8 Benefits, vacation and learning how to say stuff in Cockney 11 Where the little monsters go 11 How to keep your health bar full 12 Where you hang your hat 12 In the boroughs 12 Quick guide to some of the most popular areas 14 Ready to play? 15 Five tips before you go 16 London – the bullets 16 Wanna know more? 19 3 4 The city of many greats A place for everyone As a city, London has been around forever. Some findings go back to the Bronze Age, but the first major and anyone settlement was founded by the Romans in 43 AD. -

The Tower of London Mighty Fortress, Royal Palace, Infamous Prison

The Tower of London Mighty Fortress, Royal Palace, Infamous Prison Tiernan Chapman-Apps Before the Tower William the Conqueror was a distant cousin of Edward the Confessor, he wanted to be the King of England. He said he had been promised the throne in 1051 and was meant to be supported by Harold the Earl of Wessex son and heir of the Earl of Godwin in 1064 who swore to uphold his right to be king. However Harold went back on his promise and was an usurper. Edward died having no children and both Harold and William wanted the throne. William invaded the country and Harold was killed in the battle of Hastings by an arrow and then a sword of a knight William was crowned on Christmas Day 1066 Pictures from top to bottom William the Conqueror Edward the Confessor Harold the Earl of Wessex or Harold II The building and construction Building of the Tower of London actually began just after William the Conqueror captured the city in 1066, Immediately after his coronation (Christmas 1066), William I the Conqueror began to erect fortifications on the South East corner of the site to dominate the indigenous mercantile community and to control access to the Upper Pool of London, the major port area before the construction of docks farther downstream in the 19th century. 12 years later the building of the White Tower began to take place and other defenses were developed and made bigger during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. At the end of King Edwards reign in 1307 the Tower of London was a huge and imposing castle. -

The Yeomen of the Guard Or, the Merryman and His Maid

The Yeomen of the Guard or, The Merryman and His Maid THE CAST Colonel Fairfax (under sentence of death) ................................ Josh Kowitz Sergeant Meryll (of the Yeomen of the Guard) ................. Waldyn Benbenek Phoebe Meryll (his daughter) ................................................... Lara Trujillo Leonard Meryll (his son) ...................................................... Michael Burton Jack Point (a strolling jester) ............................................. Jacob Wellington Elsie Maynard (a strolling singer) .......................................... Quinn Shadko Wilfred Shadbolt (Head Jailer and Assistant Tormentor) Stephen Mumbert Sir Richard Cholmondeley (Lieutenant of the Tower) ................. Jim Ahrens Dame Carruthers (Housekeeper to the Tower) ............................... Deb Haas Kate (her niece) ....................................................................... Missy Griffin First Yeoman .................................................................................. Tom Berg Second Yeoman ......................................................................... Wric Larsen First Citizen............................................................................. Anthony Rohr The Headsman / Second Citizen ................................... Christopher Michela Chorus of Citizens: Jonathan Flory Holly MacDonald Noelle French Mary Mescher Benbenek Zach Garcia Christopher Michela Mary Gregory Johna Miller Missy Griffin Charlotte Morrison Shawn Holt Anthony Rohr Kelly Houlehan Rhea -

Hosehold Cavalry

Changing the Guard, Guarding the Change of History 1. INTRODUCTION The Queen's Guard and Queen's Life Guard are the names given to contingents of cavalry and infantry soldiers charged with guarding the official royal residences in London. The British Army has had regiments of both Horse Guards and Foot Guards since before the restoration of King Charles II, and, since 1660, these have been responsible for guarding the Sovereign Palaces. The Queen's Guard and Queen's Life Guard is mounted at the royal residences which come under the operating area of London District, which is responsible for the administration of the Household Division; this covers Buckingham Palace, St James's Palace and the Tower of London, as well as Windsor Castle. The Queen's Guard is also mounted at the sovereign's other official residence, the Palace of Holyroodhouse, but not as regularly as in London. In Edinburgh, the guard is the responsibility of the resident infantry battalion at Redford Barracks. It is not mounted at the Queen's private residences at Sandringham or Balmoral. The Queen's Guard is the name given to the contingent of infantry responsible for guarding Buckingham Palace and St. James's Palace (including Clarence House) in London. The guard is made up of a company of soldiers from a single regiment, which is split in two, providing a detachment for Buckingham Palace and a detachment for St James's Palace. Because the Sovereign's official residence is still St James's, the guard commander (called the 'Captain of the Guard') is based there, as are the regiment's colours. -

William Siborne's New Waterloo Model

WILLIAM SIBORNE’S NEW WATERLOO MODEL William Siborne’s New Waterloo Model PHILIP ABBOTT Royal Armouries, UK Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT William Siborne has played a major role in our understanding of the battle of Waterloo, and has left a lasting legacy in the form of two large models, a collection of eyewitness accounts, and a history of the campaign that has remained in print since it was first published in 1844. But Siborne's history has become clouded in controversy, and as a result his skills as a model maker have gone largely unnoticed. A recent project to conserve his New Waterloo Model at the Royal Armouries in Leeds has presented a unique opportunity to review this aspect of his work, and to appreciate some of the subtleties of this complex piece of art. William Siborne is best known for his History of the War in France and Belgium, which despite being criticised for its over reliance on British sources, remains one of the most cited works on the Waterloo campaign. However, as a young man his interest was in topographical surveying, plan-drawing and modelling, and it was as a result of his published work on these subjects that he was asked to construct a model of the battlefield of Waterloo for the United Services Museum. The project consumed twenty years of his life, and the hundreds of personal accounts from Waterloo veterans that he collected during the course of his research, and the history that he produced were mere bi-products of his model making.