Guidance on Part 2 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Full Text In

The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS Future Academy ISSN: 2357-1330 https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.40 UUMILC 2017 9TH UUM INTERNATIONAL LEGAL CONFERENCE THE ONLINE SOCIAL NETWORK ERA: ARE THE CHILDREN PROTECTED IN MALAYSIA? Zainal Amin Ayub (a)*, Zuryati Mohamed Yusoff (b) *Corresponding author (a) School of Law, College of Law, Government & International Studies, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia, [email protected], +604 928 8073 (b) School of Law, College of Law, Government & International Studies, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia, [email protected], +604 928 8089 Abstract The phenomenon of online social networking during the age of the web creates an era known as the ‘Online Social Network Era’. Whilst the advantages of the online social network are numerous, the drawbacks of online social network are also worrying. The explosion of the use of online social networks creates avenues for cybercriminals to commit crimes online, due to the rise of information technology and Internet use, which results in the growth of the Internet society which includes the children. The children, who are in need of ‘extra’ protection, are among the community in the online social network, and they are exposed to the cybercrimes which may be committed against them. This article seeks to explore and analyse the position on the protection of the children in the online society; and the focus is in Malaysia while other jurisdictions are referred as source of critique. The position in Malaysia is looked into before the introduction of the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017. -

Sexual Offences

Sexual Offences Definitive Guideline GUIDELINE DEFINITIVE Contents Applicability of guideline 7 Rape and assault offences 9 Rape 9 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 1) Assault by penetration 13 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 2) Sexual assault 17 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 3) Causing a person to engage in sexual activity without consent 21 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 4) Offences where the victim is a child 27 Rape of a child under 13 27 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 5) Assault of a child under 13 by penetration 33 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 6) Sexual assault of a child under 13 37 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 7) Causing or inciting a child under 13 to engage in sexual activity 41 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 8) Sexual activity with a child 45 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 9) Causing or inciting a child to engage in sexual activity 45 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 10) Sexual activity with a child family member 51 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 25) Inciting a child family member to engage in sexual activity 51 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 26) Engaging in sexual activity in the presence of a child 57 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 11) Effective from 1 April 2014 2 Sexual Offences Definitive Guideline Causing a child to watch a sexual act 57 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 12) Arranging or facilitating the commission of a child sex offence 61 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 14) Meeting a child following sexual grooming 63 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 15) Abuse of position of trust: -

Report Into the Law and Procedures in Serious Sexual Offences in Northern Ireland Part 1 Sir John Gillen

Gillen Review Report into the law and procedures in serious sexual offences in Northern Ireland Part 1 Sir John Gillen gillenreview.org Gillen Review Report into the law and procedures in serious sexual offences in Northern Ireland Part 1 Sir John Gillen Preface And if there may seem to be a weight of tradition against change, at least it is worth remembering that the apparent heresies of one generation become the orthodoxies of the next. The ultimate validity of any social measure will depend not upon its antecedents but upon its current and future utility. Sir Owen Woodhouse1 Sexual crime is one of the worst violations of human dignity. It can deeply traumatise the victims, their family and even whole communities. Serious sexual offences in general and rape in particular are crimes of alarming prevalence. They are unique in the way they strike at the bodily integrity and self-respect of the victim. All genders, children and people of all ages, classes and ethnicities can become victims. It happens across all cultures and in some cultures, including here in Northern Ireland, shame and social pressures will prevent it being reported. These crimes are a blight on our society with profound consequences for victims and for society at large. Deep concerns about how serious sexual offences are processed and determined have been expressed for several years. In the wake of recent trials of such offences both here and in England and Wales, public disquiet about the law and procedures governing serious sexual offences has clearly grown. Hence the Criminal Justice Board, which exists to oversee reform, change and openness in the criminal justice system, commissioned me on 24 April 2018 to undertake an independent review of arrangements around delivery of justice in serious sexual offences. -

1 Child Pornography Alisdair A. Gillespie.* It Would Seem, At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lancaster E-Prints Child Pornography Alisdair A. Gillespie.* It would seem, at one level, to be somewhat gratuitous to include an article on child pornography in a special issue on ‘Dangerous Speech’. Child pornography would seem to obviously meet the criteria of dangerous speech, with no real discussion required. However, as will be seen in this article, this is not necessarily the case. There remain a number of controversial issues that potentially raise both under-criminalisation and over-criminalisation. This article seeks to critique the current law of child pornography using doctrinal methods, to assess its impact and reach. It will do this by breaking down the definition of child pornography into its constituent parts, identifying how the law has constructed these elements and whether they contribute to an effective legislative response to tackling the sexual exploitation of children through sexual images. The article concludes that there are some areas that require adjustment and puts forward the case for limited legislative changes to ensure that exploitative pictures are criminalised but in such a way that innocent pictures are not. DEFINING CHILD PORNOGRAPHY There is no single definition of ‘child pornography’ and indeed the term itself remains controversial.1 In order to understand the interaction between child pornography and dangerous speech, it is necessary to consider the definition of child pornography. The difficulty with this is that there are hundreds of different definitions available. Even international law cannot agree, with different definitions being used in the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography2 (hereafter ‘OPSC’) and the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse3 (hereafter ‘Lanzarote Convention’4). -

Issues Paper on Cyber-Crime Affecting Personal Safety, Privacy and Reputation Including Cyber-Bullying (LRC IP 6-2014)

Issues Paper on Cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying (LRC IP 6-2014) BACKGROUND TO THIS ISSUES PAPER AND THE QUESTIONS RAISED This Issues Paper forms part of the Commission’s Fourth Programme of Law Reform,1 which includes a project to review the law on cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying. The criminal law is important in this area, particularly as a deterrent, but civil remedies, including “take-down” orders, are also significant because victims of cyber-harassment need fast remedies once material has been posted online.2 The Commission seeks the views of interested parties on the following 5 issues. 1. Whether the harassment offence in section 10 of the Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act 1997 should be amended to incorporate a specific reference to cyber-harassment, including indirect cyber-harassment (the questions for which are on page 13); 2. Whether there should be an offence that involves a single serious interference, through cyber technology, with another person’s privacy (the questions for which are on page 23); 3. Whether current law on hate crime adequately addresses activity that uses cyber technology and social media (the questions for which are on page 26); 4. Whether current penalties for offences which can apply to cyber-harassment and related behaviour are adequate (the questions for which are on page 28); 5. The adequacy of civil law remedies to protect against cyber-harassment and to safeguard the right to privacy (the questions for which are on page 35); Cyber-harassment and other harmful cyber communications The emergence of cyber technology has transformed how we communicate with others. -

Post-Release Controls for Sex Offenders in the US and UK

1 Post-Release Controls for Sex Offenders in the U.S. and UK Roxanne Lieb * Associate Director Washington State Institute for Public Policy Olympia, Washington, United States Hazel Kemshall Professor DeMontford University Leicester, United Kingdom Terry Thomas Professor of Criminal Justice Studies School of Social Sciences Leeds Metropolitan University Leeds, United Kingdom *contact author 110 Fifth Ave. SE PO Box 40999 Olympia, WA 98504-0999 [email protected] phone (360) 586-2768 fax (360) 586-2793 2 Key Words: Megan’s Law; sex offender policy; registration and notification laws Abstract In recent years, both the United States and United Kingdom have developed numerous innovations in legal efforts to protect society from sex offenders. Each country has adopted special provisions for sex offenders. In particular, governments have focused on forms of social control after release from incarceration and probation. These policy innovations for this category of offenders have been more far reaching than those for any other offender population. The two jurisdictions have adopted policies with similar goals, but the selected strategies have important differences. Generally speaking, the U.S. has favored an ever-expanding set of policies that place sex offenders into broad categories, with few opportunities that distinguish the appropriate responses for individual offenders. The UK government observed the proliferation of Megan’s Laws1 in the U.S., and deliberately chose to establish carefully controlled releases of information, primarily relying on governmental agencies to work in multi-disciplinary groups and make case-specific decisions about individual offenders. Although the UK policy leaders expressed significant concern that the public’s response to knowing about identified sex offenders living in the community would result in vigilantism, to date the results have not born out this fear. -

Guidance on Review of Indefinite Notification Requirements

GUIDANCE ON REVIEW OF INDEFINITE NOTIFICATION REQUIREMENTS ISSUED UNDER SECTION 91F OF THE SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT 2003 Guidance On Review Of Indefinite Notification Requirements Issued Under Section 91F Of The Sexual Offences Act 2003 2 Guidance On Review Of Indefinite Notification Requirements Issued Under Section 91F Of The Sexual Offences Act 2003 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Current arrangements 5 Aims 6 Principles 6 What is new? 6 Cross-force issues 7 Devolved administration 7 The Process 8 Process Map 8 Eligibility 9 Stage 1: Application and acknowledgment 10 Engagement with relevant offenders 10 Qualifying dates 10 Making an application 10 Acknowledgement and notice to responsible bodies 11 Stage 2: Review and determination 12 Review of application 12 Factors for determination 12 Standard checks 14 Information from responsible bodies 14 Risk assessment tools 14 Stage 3: Decision 16 Determination of review 16 Consulting with victims 16 Stage 4: Appeals Process 18 Stage 5: Further review periods 19 Maintaining records 19 Frequently asked questions 20 Definitions 22 Annexes 24 3 Guidance On Review Of Indefinite Notification Requirements Issued Under Section 91F Of The Sexual Offences Act 2003 INTRODUCTION 1. This statutory guidance is issued by the 5. If you have any queries regarding this Secretary of State under section 91F(1) of guidance, please contact: the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (“the 2003 Act”), which was inserted into the 2003 Act Interpersonal Violence: Policy & Delivery on 30 July 2012 by the Sexual Offences Act Team, Violent and Youth Crime Prevention 2003 (Remedial) Order 2012 (“the remedial Unit, Home Office, 4th Floor, Fry Building, order”). -

Download Thepdf

Volume 59, Issue 5 Page 1395 Stanford Law Review KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Law Review at 59 STAN. L. REV. 1395 (2007). For information visit http://lawreview.stanford.edu. KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker* INTRODUCTION: THE DYNAMICS OF COUNTER-TERRORISM POLICIES AND LAWS................................................................................................ 1395 I. CONTROL ORDERS ..................................................................................... 1403 A. Background to the Enactment of Control Orders............................... 1403 B. The Replacement System..................................................................... 1408 1. Control orders—outline................................................................ 1408 2. Control orders—contents and issuance........................................ 1411 3. Non-derogating control orders..................................................... 1416 4. Derogating control orders............................................................ 1424 5. Criminal prosecution.................................................................... 1429 6. Ancillary issues............................................................................. 1433 7. Review by Parliament and the Executive...................................... 1443 C. Judicial Review.................................................................................. -

Rights of Women from Report to Court a Handbook for Adult Survivors of Sexual Violence Rights of Women Aims to Achieve Equality, Justice and Respect for All Women

Rights of Women From Report to Court A handbook for adult survivors of sexual violence Rights of Women aims to achieve equality, justice and respect for all women. Rights of Women advises, educates and empowers women by: ● Providing women with free, confidential legal advice by specialist women solicitors and barristers. ● Enabling women to understand and benefit from their legal rights through accessible and timely publications and training. ● Campaigning to ensure that women’s voices are heard and law and policy meets all women’s needs. ISBN 10: 0-9510879-6-7 ISBN 13: 978-0-9510879-6-1 Rights of Women, 52-54 Featherstone Street, London EC1Y 8RT For advice on family law, domestic violence and relationship breakdown telephone 020 7251 6577 (lines open Tuesday to Thursday 2-4pm and 7-9pm, Friday 12-2pm). For advice about sexual violence, immigration or asylum law telephone 020 7251 8887 (lines open Monday 11am-1pm and Tuesday 10am-12noon). Alternative formats of this book are available on request. Please contact us for further information. Admin line: 020 7251 6575/6 Textphone: 020 7490 2562 Fax: 020 7490 5377 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rightsofwomen.org.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of Rights of Women. To receive further copies of this publication, please contact Rights of Women. Disclaimer: The guide provides a basic overview of complex terminology, rights, laws, processes and procedures for England and Wales (other areas such as Scotland have different laws and processes). -

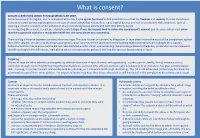

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he/she did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical disabilities, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Increasing the Notification Requirements for Registered Sex Offenders Under Part 2 of the Sexual Offences

Title: Increasing the Notification Requirements of Registered Sex Impact Assessment (IA) Offenders under Part 2 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 Date: 05/03/2012 IA No: HO0051 Stage: Final Lead department or agency: Source of intervention: Domestic Home Office Other departments or agencies: Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Faye Ricketts 0207 035 8430 Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: RPC Opinion Status Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £-8.7m N/A N/A N/A N/A What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Under existing legislation (part 2 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003) registered sex offenders are required to notify name, address, date of birth, national insurance number, and travel outside the UK of a period of 3 days or more to the police annually or whenever their details change. Not notifying foreign travel of less than 3 days has been identified as a loop hole. Police will also be able to more effectively manage offenders if they are required to notify weekly if registered as 'no fixed abode', notify if living in a household with a minor, notify passport and bank account details, and provide proof of identification at each notification. Government intervention is necessary to prevent exploitation of the system and enable robust offender management. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? Public safety will always be a top priority for the Government. -

Cyber-Enabled Crimes – Sexual Offending Against Children

Cyber crime: A review of the evidence Research Report 75 Chapter 3: Cyber-enabled crimes - sexual offending against children Dr. Mike McGuire (University of Surrey) and Samantha Dowling (Home Office Science) October 2013 Cyber crime: A review of the evidence Chapter 3: Cyber-enabled crimes – sexual offending against children Home Office Research Report 75 October 2013 Dr. Mike McGuire (University of Surrey) and Samantha Dowling (Home Office Science) 1 Acknowledgements With thanks to: Andy Feist, Angela Scholes, Ian Caplan, Justin Millar, Steve Bond, Jackie Hoare, Jenny Allan, Laura Williams, Amy Everton, Steve Proffitt, John Fowler, David Mair, Clare Sutherland, Magali Barnoux, Mike Warren, Amanda White, Sam Brand, Prof. Majid Yar, Dr.Steve Furnell, Dr. Jo Bryce, Dr Emily Finch and Dr. Tom Holt. Disclaimer The views expressed in this report are those of the authors, not necessarily those of the Home Office (nor do they represent Government policy). 2 Contents What are cyber-enabled crimes? 4 Key findings: What is known about online grooming? 5 Scale and nature of online grooming 5 Characteristics of Victims 10 Characteristics of Offenders 11 Key findings: What is known about the production, possession and distribution of online indecent images of children? 14 Scale and nature of online indecent images of children 14 Characteristics of Victims 18 Characteristics of Offenders 19 References 22 3 Cyber crime: A review of the evidence Chapter 3: Cyber-enabled crimes – sexual offending against children What are cyber-enabled crimes? Cyber-enabled crimes are traditional crimes, which can be increased in their scale or reach by use of computers, computer networks or other forms of information communications technology (ICT).