Student Days (1903-1911)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMES FRASER, LAIRD of BREA —Probed Many Hearts, Beginning with His Own

A LEX AN i:)EF< ‘Dr. Whyte has at last written his “Life of Christ.”’— Expository Times. Large Crown 87jo. Price 35. bd. net. THE WALK, CONVERSATION AND CHARACTER OF JESUS CHRIST OUR LORD ‘ Dr. Alexander Whyte’s book commands, like all its writer’s works, the attention of the reader. The author has great dramatic power, and a marked felicity of expression. Dr. Whyte uses the imagery, and even some of the catchwords, of a Calvinism of the past ; but he manages to put new life into them, and to show, sometimes with startling clearness, the lasting truth within the perishable formula.’—Spectator. ‘ It is distinguished by the exegetical and literary qualities that characterise all Dr. Whyte’s writings. His preaching is always intensely earnest, it is thoroughly evangelical, and Dr. Whyte never fails to enforce its lessons by illustrations drawn from his everyday experience, whether in the study or in pastoral visitation.’—Scotsman. ‘ Will rank with every competent judge of Dr. Whyte’s expositions as his very best book. It represents Dr. Whyte at his best. It is practically a life of Christ—and it is that life on its inner side. The titles of the lectures are expressed in a characteristic way, and the treatment of the subject is fresh and original in every case.’—Christian Leader. JAMES FRASER, LAIRD OF BREA —Probed many hearts, beginning with his own. Yea, this man’s brow, like to a title-leaf, Foretells the nature of a tragic volume: Thou tremblest, and the whiteness in thy cheek Is apter than thy tongue to tell thine errand. -

Angus and Mearns Directory and Almanac, 1846

21 DAYS ALLOWED FOR READING THIS BOOK. Overdue Books Charged at Ip per Day. FORFAR PUBLIC LIBRARY IL©CAIL C©iLILECirD©IN ANGUS - CULTURAL SERVICES lllllllllillllllllllllllllllillllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Presented ^m . - 01:91^ CUStPI .^HE isms AND MSARNS ' DIRECTORY FOR 18^6 couni Digitized by tlie Internet Arcliive in 2010 witli funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/angusmearnsdirec1846unse - - 'ir- AC'-.< u —1 >- GQ h- D >- Q. a^ LU 1*- <f G. O (^ O < CD i 1 Q. o U. ALEX MAC HABDY THE ANGUS AND MEAENS DIRECTORY FOR 1846, CONTAINING IN ADDITION TO THE WHOLE OP THE LISTS CONNECTED WITH THE COUNTIES OP FORFAR AND KINCARDINE, AND THE BURGHS OP DUNDEE, MONTROSE, ARBROATH, FORFAR, KIRRIEMUIR, STONEHAVEN, &c, ALPHABETICAL LISTS 'of the inhabitants op MONTROSE, ARBROATH, FORFAR, BRECBIN, AND KIRRIEMUIR; TOGETHEK WITH A LIST OF VESSELS REGISTERED AT THE PORTS OF MONTROSE, ARBROATH, DUNDEE, PERTH, ABERDEEN AND STONEHAVEN. MONTROSE PREPARED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMUI^ \VATT, STANDARD OFFICE, AND SOIiD BY ALL THE BOOKSELLERS IN THE TWO COUNTIES. EDINBURGH: BLACKWOOD & SON, AND OLIVER &c BOYD, PRINTED AT THE MONTROSE STANDARD 0FFIC5 CONTENTS. Page. Page Arbroath Dfrectory— Dissenting Bodies 178 Alphabetical List of Names 84 Dundee DtRECTORY— Banks, Public Offices, &c. 99 Banks, Public Offices, &c. 117 Burgh Funds . 102 Burgh Funds .... 122 Biiri^h Court 104 Banking Companies (Local) 126 128 Bible Society . • 105 Burgh Court .... Coaches, Carriers, &c. 100 Building Company, Joint-Stock 131 Comraerciiil Associations . 106 Coaches 11« Cliarities . , 106 Carriers 119 Educational Institutions . 104 Consols for Foreign States 121 Fire and Life Insurance Agents 101 Cemetery Company 124 Friendly Societies . -

The Forfar Directory and Yearbook 1909

m. fkJ* ''^,: FORFAR PUBLIC LIBRARY IL©CA[L C©ILILiCTrD©IHI No. Presented by ANGUS - CULTURAL SERVICES 3 8046 00947 097 1 ^c^c^ 21 DAYS ALLOWED FOR READING THIS BOOK. Overdue Books Charged at Ip per Day. of FCWQiti^ed byJbeilKternet Archive in^010,with funding from ational Library oJlScot land http://www.archive.org/details/forfardirectoryy1909unse PATTERSON BROTHERS High-class Bakers, Confectioners and Pastrycooks, 27 WEST HIGH STREET, and 165 EAST HIGH STREET, FORFAR. Our Bread Aw^ards. SILVER MEDAL, London 1904, SILVER CHALLENGE SHIELD of Scotland, 1905, GOLD MEDAL, Edinburgh 1905, DIPLOMA, London 1904. CERTIFICATE of HONOUR for High Excellence of Quality ^ Workmanship in Breadmaking, Glasgow 1906. GOLD MEDAL, for Rolls, London 1908. • ^ m ^ • - - - f0t- A TRIAL ORDER SOLICITED. -«I " f Ladies' Si Gent.'s High-class TAILORING Lo^vcst Cash Prices Jarvis Brothers . FORFAR DIRECTORY: MALE HOUSEHOLDERS. Abel, John R. Druggist 1 Sparrowcroft Aberdein, James Vintner 67 Queen street Adam, Charles Shoemaker 13 Osnaburgh street Adam, David Mason 17 Wellbraehead Adam, James Gardener 32 Glamis Road Adam, James Carter 51 Queen street Adam, James Factory worker 182 East High street Adam, Robert Boots Dundee Road Adam, William Postman 3 1 South street Adams, George Accountant 58-60 Dundee Road Adams, Henry Shuttlemaker 51 North street Adams, Joseph Slater 4 Nursery street Adamson, Alexander Builder 4 Jamieson street Adarason, Alexander, jun. Mason Jamieson street Adamson, David Builder Tarfside, Taylor street Adamson, George Lorryman 48 South street -

Alexander Whyte Lessons to Learn

Alexander Whyte Lessons to Learn What do we make of Alexander Whyte? His books, unlike those of many of his liberal contemporaries, are still in print and are popular with Christians all over the world. Christian Focus publish his famous Bible Characters. Other books of his in print include: Lord Teach Us to Pray, Samuel Rutherford and some of his correspondents, Bunyan Characters and An Exposition of the Shorter Catechism. He was a prolific writer and was widely regarded as the greatest Scottish preacher of his day. And yet there is something troubling about him. And it is to be found in his books. I first heard of Alexander Whyte from my childhood minister in Stornoway, the Rev Kenneth MacRae. He warned us against using Whyte’s Exposition of the Shorter Catechism which provides what is in many ways a helpful explanation of the Westminster Shorter Catechism. I have used it myself along with other books in preaching through the Catechism. Recently I read The Life of Alexander Whyte by G F Barbour which was first published in 1923 shortly after Whyte’s death. To me it was a fascinating and yet shocking and disturbing book. There was so much that was good in the life of Whyte but at the same time there was so much confusion, lack of discernment and dangerous false teaching. It now became clear why Whyte repeatedly and approvingly quoted liberal and Roman Catholic writers in his Exposition of the Shorter Catechism. Whyte’s long active life (1836-1921) spans the second half of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth. -

Dogma and History in Victorian Scotland

Dogma and History in Victorian Scotland Todd Regan Statham Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University Montreal, Quebec February 2011 A Thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Todd Regan Statham Table of Contents Abstract v Résumé vii Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations x Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Scottish Presbyterian Church ‘in’ History 18 1.1. Introduction 18 1.2. Church, Scripture, and Tradition 19 1.2.1. Scripture and Tradition in Roman Catholicism 20 1.2.2. Scripture and Tradition in Protestantism 22 1.2.3. A Development of Dogma? 24 1.3. Church, Doctrine, and History 27 1.3.1. Historical Criticism of Doctrine in the Reformation 29 1.3.2. Historical Criticism of Doctrine in the Enlightenment 32 1.3.3. Historical Criticism of Doctrine in Romanticism and Idealism 35 1.4. Church: Scottish and Reformed 42 1.4.1. The Scottish Church and the Continent 42 1.4.2. Westminster Calvinism 44 1.4.3. The Evangelical Revival 48 1.4.4. Enlightened Legacies 53 1.4.5. Romantic Legacies 56 1.4.6. The Free Church and the United Presbyterians in Victorian Scotland 61 1.5. Conclusion 65 Chapter 2: William Cunningham, John Henry Newman, and the Development of Doctrine 67 2.1. Introduction 67 2.2. William Cunningham 69 2.3. An Essay on the Development of Doctrine 72 2.3.1. Against “Bible Religion” and the Church Invisible 74 2.3.2. Cunningham on Scripture and Church 78 2.3.3. The Theory of Development 82 ii 2.3.4. -

“Boars in God's Vineyard”

THE ROMANS SERIES “BOARS IN GOD’S VINEYARD” Romans 16:17-20 STUDY (45) Rev (Dr) Paul Ferguson Calvary Tengah Bible Presbyterian Church Shalom Chapel, 345 Old Choa Chu Kang Road, Singapore 698923 www.calvarytengah.com 26 February 2012 On the 15 June 1520, Pope Leo X issued a document of excommunication known as a papal bull, which was circulated around Europe. The writing began, “Arise, O Lord and judge Thy cause. A wild boar has invaded Thy vineyard.” The papal bull was issued to condemn the beliefs of a wild boar named Martin Luther, who simply declared that the Bible taught a man was justified by faith by grace alone through faith alone. Pope Leo X likened the Roman Catholic Church to God’s vineyard and argued that Luther was seeking to destroy the church. The irony was that it was Leo X who was seeking to destroy God’s true vineyard. He had almost bankrupted the RCC by his extravagance. This eventually led him to sell off indulgences to sin to raise funds for the church. Such action helped spark of the Protestant Reformation and the greatest revival in the true church since Pentecost. Rather than being a wild boar, Luther became a mighty instrument in God’s hand to reach countless thousands of precious souls with the light of the true Gospel. The NT is full of warnings about wild boars, who rampage through the church of Jesus Christ. Yes, Christ is building the church and the gates of hell will never prevail against it, but that does not mean that Satan will not try. -

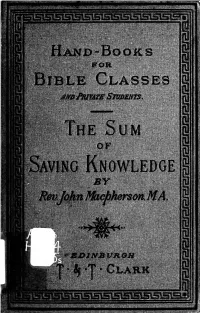

The Sum of Saving Knowledge

BR 45 .H36 v.2A Dickson, David, 15837-1663. The sum of saving knowledge HANDBOOKS BIBLE CLASSES AND PRIVATE STUDENTS. EDITED by/ REV. MARCUS DODS, D.D., AND REV. ALEXANDER WHYTE, D.D. THE SUM OF SAV/NG KNOWLEDGE. BY REV, JOHN MACPHERSON, M.A. EDINBURGH: T. & T. CLARK, 38 GEORGE STREET. PRINTED BY MORRISON AND GIBB, FOR T. & T. CLARK, EDINBURGH. LONDON HAMILTON, ADAMS, AND CO. DUBLIN, .... GEORGE HERBERT. NEW YORK, .... SCRIBNER AND WELFORD. THE SUM OF SAVING KNOWLEDGE. TOttJ KntrotJuction antr Notes, / BY REV. JOHN MACPHERSON, M.A., FINDHORN. EDINBURGH: T. & T. CLARK, 38 GEORGE STREET. v>" '\ '-: JUL \ ,c',5 -^ ><>>: CONTENTS. [ntroduction. 7-8 I. Our Condition by Nature— §1. Preliminary. The Mystery of the Godhead, 9-22 § 2. Doctrine of Creation and Covenant of Works, 23-42 § 3. The Beginnings of Human Sin, 42-53 II. The Remedy Provided in Jesus Christ— § I. The Counsels of Eternity, . , 54-61 § 2. Covenant of Redemption—Election and Incarna- tion, ...... 61-89 § 3. Christ as Prophet, Priest, and King, 90-97 III. Means toward Partaking of the Covenant— §1. The Means of Grace, . 98-113 § 2. Substantial Agreement of Old and New Dis- pensations, . 113-117 IV. Blessings conveyed to the Elect by those Means— § I. Spirit's Work on the Persons of the Elect, 118-125 § 2, Spirit's Work in changing the State of the Elect, . 125-133 INTRODUCTION, The authorship of this short treatise on Christian doctrine, which is made the basis of the following notes, is ascribed to the celebrated Scottish divine, Mr. David Dickson. This able theo- logian and valiant defender of the faith was born in Glasgow in 1583. -

Samuel Rutherford and Some of His Correspondents By

Samuel Rutherford and Some of His Correspondents by Alexander Whyte LECTURES DELIVERED IN ST. GEORGE'S FREE CHURCH EDINBURGH: BY ALEXANDER WHYTE, D.D. Table of Contents I. JOSHUA REDIVIVUS II. SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND SOME OF HIS EXTREMES III. MARION M'NAUGHT IV. LADY KENMURE V. LADY CARDONESS VI. LADY CULROSS VII. LADY BOYD VIII. LADY ROBERTLAND IX. JEAN BROWN X. JOHN GORDON OF CARDONESS, THE YOUNGER XI. ALEXANDER GORDON OF EARLSTON XII. WILLIAM GORDON, YOUNGER OF EARLSTON XIII. ROBERT GORDON OF KNOCKBREX XIV. JOHN GORDON OF RUSCO XV. BAILIE JOHN KENNEDY XVI. JAMES GUTHRIE XVII. WILLIAM GUTHRIE XVIII. GEORGE GILLESPIE XIX. JOHN FERGUSHILL XX. JAMES BAUTIE, STUDENT OF DIVINITY XXI. JOHN MEINE, JUNIOR, STUDENT OF DIVINITY XXII. ALEXANDER BRODIE OF BRODIE XXIII. JOHN FLEMING, BAILIE OF LEITH XXIV. THE PARISHIONERS OF KILMACOLM I JOSHUA REDIVIVUS 'He sent me as a spy to see the land and to try the ford.' - Rutherford. SAMUEL RUTHERFORD, the author of the seraphic Letters, was born in the south of Scotland in the year of our Lord 1600. Thomas Goodwin was born in England in the same year, Robert Leighton in 1611, Richard Baxter in 1615, John Owen in 1616, John Bunyan in 1628, and John Howe in 1630. A little vellum-covered volume now lies open before me, the title-page of which runs thus:—'Joshua Redivivus, or Mr. Rutherford's Letters, now published for the use of the people of God: but more particularly for those who now are, or may afterwards be, put to suffering for Christ and His cause. By a well-wisher to the work and to the people of God. -

Bunyan Characters (2Nd Series)

Bunyan Characters (2nd Series) Alexander Whyte Bunyan Characters (2nd Series) Table of Contents Bunyan Characters (2nd Series)..............................................................................................................................1 Alexander Whyte...........................................................................................................................................2 IGNORANCE................................................................................................................................................3 LITTLE−FAITH............................................................................................................................................6 THE FLATTERER......................................................................................................................................10 ATHEIST.....................................................................................................................................................13 HOPEFUL....................................................................................................................................................17 TEMPORARY.............................................................................................................................................21 SECRET.......................................................................................................................................................25 MRS. TIMOROUS......................................................................................................................................29 -

Heartbeats of the Holy a Philosophy of Ministry Keith E

Heartbeats of the Holy A Philosophy of Ministry Keith E. Knauss www.christlifemin.org DEDICATED To The Exaltation of the Savior and The Encouragement of His Servants Contents INTRODUCTION . 1 1. CALLING AND COMPULSION . 3 2. PREACHER AND PULPIT . 5 3. CHARACTER AND CONDUCT . 7 4. PREACHING AND PRAYER . 9 5. BURDEN AND BLESSING . 12 6. SAINT AND SINNER . 15 7. WEAKNESS AND WANTS . 18 8. DISCOURAGEMENT AND DEPRESSION . 20 9. PERILS AND PRIVILEGES . 23 10. MAN AND MESSAGE . 26 11. THE SPIRIT AND SUCCESS . 29 12. POLLEN AND PREACHING . 32 13. BOOKS AND BUSYNESS . 33 14. COMMITMENT AND COMPROMISE . 35 15. ENTERTAINMENT AND EXHORTATION . 37 16. THE WONDER AND THE WORD . 39 17. HELPMATE AND HOME . 41 18. SCHOLAR AND STUDENT . 44 19. COMFORTER AND COUNSELOR . 47 20. CHURCHES AND CHANGES . 50 21. VITALITY AND VISION . 53 22. PRESENT AND PROSPECT . 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 58 INTRODUCTION What a movement that was when the blessed Holy Spirit, moved with infinite compassion, reached down and gathered up this sin-stricken world in His arms and brooded over it with unspeakable burden. The burden for a dying world has not passed away, it has been passed on, in a measure, to those who have felt the calling hand of God strong upon them. Holy men of God have come walking bowed beneath the immeasurable weight of the Divine Word and a Demanding Work. They have come treading through the tumult of their times, the voice of One crying in the wilderness. Such men have been declared the off-scouring of a word unworthy of them, pouring out upon their own hearts a loathsome load of contempt and condemnation at their own unworthiness and unfitness. -

Books On-Line: Complete List by Title

Books On-line: Complete List by Title COMPLETE LIST BY TITLE List too long? See the main on-line books page to browse it in segments, or search for particular books. Please suggest any additions to [email protected]. Additional titles not locally indexed can be found at the other repositories listed on the main on-line books page. See also listings by author. ● "...For the Hour of His Judgment Is Come..." by Annikki Matthan (HTML in Finland) ● The "B. O. W. C.": A Book for Boys (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1869) by James De Mille (page images at canadiana.org) ● The "Bab" Ballads by William S. Gilbert (Gutenberg text) ● "Both Sides Told," or, Southern California As It Is by Mary C. Vail (HTML at LOC) ● "Bringing the Ranks Up to the Standard" by Emma L. Burnett (page images at canadiana.org) ● "Cato" on Constitutional "Money" and Legal Tender (Charleston: Evans & Cogswell, 1862) by Thomas Jefferson Withers (HTML and TEI at UNC) ● "Dot It Down": a Story of Life in the North-West (Toronto : Hunter, Rose, 1871) by Alexander Begg (page images at canadiana.org) ● "Esmeralda" Waltz-Lanciers by William W. Florence (HTML and page images at LOC) ● "Greenbacks" by Observer (page images at MOA) ● "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder by Vladimir Ilich Lenin, trans. by Julius Katzer (HTML at marxists.org) ● "Little Sheaves" Gathered While Gleaning After Reapers by Caroline M. Nichols Churchill (HTML at LOC) ● "Mademoiselle Miss": Letters from an American Girl Serving with the Rank of Lieutenant in a French Army Hospital at the Front -

Bunyan Characters Online

CLj9Y [Read free] Bunyan Characters Online [CLj9Y.ebook] Bunyan Characters Pdf Free Alexander Whyte ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1588768 in Books 2012-01-21 9.00 x .25 x 6.00l, #File Name: 1469946696108 pages | File size: 43.Mb Alexander Whyte : Bunyan Characters before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Bunyan Characters: 6 of 6 people found the following review helpful. Character CountsBy MarfieinVAHow is character formed and how important is our character? Here's what Alexander Whyte says in his introduction, "For acts, often repeated, gradually become habits, long enough continued, settle and harden and solidify into character." [Loc. 42]. It's not every day that you find a book like this, a collective biography of fictional characters from a fictional book. Next to the Bible, The Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan has stood the test of time. If you've ever wondered from whence came the character of Evangelist who was based on John Gifford, an ex-royalist major, who escaping the gallows after Cromwell's victory at Maidstone, later became a Christian and led Bunyan to Christ. Learn the backgrounds, biblical and biographical behind Obstinate and Pliable, Mr. Worldly- Wise Man, Help, Great-heart and Good Will, the gatekeeper of the little wicket gate where Christian went to be rid of the heavy burden of sin on his back. Alexander Whyte, 1836-1921, was most known for his fiery preaching, but also as Scottish Covenanter and mystic.