Haarr Silje.Pdf (1.363Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching American Literature: a Journal of Theory and Practice Summer 2013 (6:2) 13

Teaching American Literature: A Journal of Theory and Practice Summer 2013 (6:2) Who Is 'Us' and Who Is 'Them' in Don DeLillo's Cosmopolis? Hossein Pirnajmuddin, University of Isfahan, I. R. Iran Abbasali Borhan, Shiraz University, I. R. Iran Abstract Don DeLillo, in his first post-9/11 novel Cosmopolis, addresses the question of (terrorist) Other as occupying an infiltrating position within the American society as the host community. He purports to make a diagnosis of the deficiencies inherent in the West's global capitalist system which make it "vulnerable" and exposed to the terrorists' violence. Underlying DeLillo's approach toward terrorism in this novel is the discourse of American liberal cosmopolitanism in terms of which American society is portrayed as "the land of the free;" a "hybrid" society constituted by "heterogeneous" ethnicities with different systems of values and beliefs. This dynamic multiculturalism, so is claimed, brings about clashes, gaps, and cracks within the American community as a whole and accordingly jeopardizes the solidity of American culture. What is taken for granted is validity of the governmental account of terrorism. Adopting an ambiguous position toward this discourse, DeLillo both endorses it and subverts, through parody, some of its affiliated precepts. In this article, first DeLillo's insular representation of a "Cosmopolitan" America as a "superpower" is explored and then his subliminal registration of an Orientalized other evoking 9/11 "us/them" paradigm is brought to light. Keywords: Don DeLillo, Cosmopolis, American multiculturalism, us/them, Orientalism, 9/11. 1. Introduction The rippling impact of 9/11 "terrorist"1 events across American fiction has admittedly been far and wide. -

The Polis Artist: Don Delillo's Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Political Science Faculty Research and Scholarship Political Science 2016 The oliP s Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature Joel Alden Schlosser Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/polisci_pubs Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Custom Citation J. Schlosser, “The oP lis Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and Politics of Literature.” Theory & Event 19.1 (2016). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/polisci_pubs/32 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1/30/2016 Project MUSE - Theory & Event - The Polis Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature Access provided by Bryn Mawr College [Change] Browse > Philosophy > Political Philosophy > Theory & Event > Volume 19, Issue 1, 2016 The Polis Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature Joel Alden Schlosser (bio) Abstract Recent work on literature and political theory has focused on reading literature as a reflection of the damaged conditions of contemporary political life. Examining Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis, this essay develops an alternative approach to the politics of literature that attends to the style and form of the novel. The form and style of Cosmopolis emphasize the novel’s own dissonance with the world it criticizes; they moreover suggest a politics of poetic worldmaking intent on eliciting collective agency over the commonness of language. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 289 5th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2018) A Review of Paul Auster Studies* Long Shi Qingwei Zhu College of Foreign Language College of Foreign Language Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan, China Pingdingshan, China Abstract—Paul Benjamin Auster is a famous contemporary Médaille Grand Vermeil de la Ville de Paris in 2010, American writer. His works have won recognition from all IMPAC Award Longlist for Man in the Dark in 2010, over the world. So far, the Critical Community contributes IMPAC Award long list for Invisible in 2011, IMPAC different criticism to his works from varied perspectives in the Award long list for Sunset Park in 2012, NYC Literary West and China. This paper tries to make a review of Paul Honors for Fiction in 2012. Auster studies, pointing out the achievement which has been made and others need to be made. II. A REVIEW OF PAUL AUSTER‘S LITERARY CREATION Keywords—a review; Paul Auster; studies In 1982, Paul Auster published The Invention of Solitude which reflected a literary mind that was to be reckoned with. I. INTRODUCTION It consists of two sections. Portrait of an Invisible Man, the first part, is mainly about his childhood in which there is an Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is a absence of fatherly love and care. His memory of his growth talented contemporary American writer with great is full of lack of fatherly attention: ―for the first years of my abundance of voluminous works. -

Don Delillo and 9/11: a Question of Response

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 5-2010 Don DeLillo and 9/11: A Question of Response Michael Jamieson University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jamieson, Michael, "Don DeLillo and 9/11: A Question of Response" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 28. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DON DELILLO AND 9/11: A QUESTION OF RESPONSE by Michael A. Jamieson A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Marco Abel Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 DON DELILLO AND 9/11: A QUESTION OF RESPONSE Michael Jamieson, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2010 Advisor: Marco Abel In the wake of the attacks of September 11th, many artists struggled with how to respond to the horror. In literature, Don DeLillo was one of the first authors to pose a significant, fictionalized investigation of the day. In this thesis, Michael Jamieson argues that DeLillo’s post-9/11 work constitutes a new form of response to the tragedy. -

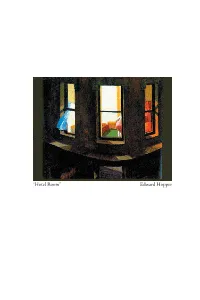

Edward Hopper the Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster

“Hotel Room” Edward Hopper The Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster James Peacock University of Edinburgh Auster contributed an extract from Moon Palace to the collection “Edward Hopper and the American Imagination,” and it is clear that Hopper’s images of alienated individuals have had a profound resonance for him. This paper employs two main ideas to compare them. First, a pivotal moment in American literature: the hotel room drama watched by Coverdale in Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance. Secondly, Aby Warburg’s concept of the “pathos formula” in art, which bypasses the problematic issue of influence, choosing instead to posit sets of inherited cultural memories. It therefore allows discussion of the re-emergence of Hawthorne’s puritan tropes of paranoid specularity and transcendence in the work of Hopper and Auster. I was never able to paint what I set out to paint. (Edward Hopper, quoted in O’Doherty 77) Words are transparent for him, great windows that stand between him and the world, and until now they have never impeded his view, have never even seemed to be there. (G 146) Somewhere in New England in the nineteenth century, a man resumes his “post” (Hawthorne 168) at his hotel room window, there to observe the boarding house opposite. Before long, a “knot of characters” enters one of the rooms, appearing before our observer as if projected onto the physi- cal stage, having been “kept so long upon my mental stage, as actors in a drama.” Longing for “a catastrophe,” some moment of high theatre to fill the epistemological void of his own soul, our voyeur gazes with increasing intensity, fabricating scenarios which, he admits, “might have been alto- gether the result of fancy and prejudice in me.” When, in one of the most compelling and influential moments in all American literature, he is spot- ted by the female protagonist and barred from the scene by the dropping of a curtain, his appetite for narrative resolution remains unsated and he is condemned to brood on his isolation once more. -

Mao II Ebook

MAO II PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Don DeLillo | 256 pages | 01 Jun 2016 | Pan MacMillan | 9781509837847 | English | London, United Kingdom Mao II PDF Book One day, he lets himself be photographed like Salinger it made him popular until he becomes involved as a spokesperson for a Swiss writer being held hostage in Beirut. All rights reserved. Throw in a clairvoyant woman, a terrorist plot, and a brilliantly realized set piece about a mass Moonie marriage, and you've got better, sharper, smarter TV than most TV. The Malleus Maleficarum caused the deaths of thousands of forward thinking women. Open Preview See a Problem? This is DeLillo after all. Only the lethal believer, the person who kills and dies for faith You just got lucky. The way they hate many of the things you hate. Print Word PDF. The novel is also about: the indifference of society personified by crowds, the act of writing as a doppelganger for terrorism, and about "messianic returns" to humanity. This offers him a chance to do what he may or may not have been planning all along: disappear completely. Now bomb-makers and gunmen have taken that territory. The limousine from "Cosmopolis" is employed once again in a blink-and-you'll-miss-it cameo. I would actually like to return to this someday, especially in this new millennium featuring the Global War on Terror and that most horrific and course-changing of days: September 11th, Let's say you do want to read a short book for a long time. Nowadays people watch and listen to terror-dominated news and their mindset and life-choices are affected by what has happened. -

“Then Catastrophe Strikes:” Reading Disaster in Paul Auster's Novels and Autobiographies « Then Catastrophe Strikes

Université Paris-Est Northwestern University École doctorale CS – Cultures et Sociétés Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences Laboratoire d’accueil : IMAGER Institut des Comparative Literary Studies Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman, EA 3958 “T HEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES :” READING DISASTER IN PAUL AUSTER ’S NOVELS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES « THEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES » : LIRE LE DÉSASTRE DANS L’ŒUVRE ROMANESQUE ET AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUE DE PAUL AUSTER Thèse en cotutelle présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Paris- Est, et de Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature de Northwestern University, par Priyanka DESHMUKH Sous la direction de Mme le Professeur Isabelle ALFANDARY et de M. le Professeur Samuel WEBER Jury Mme Isabelle ALFANDARY , Professeur à l’Université Paris-3 Sorbonne Nouvelle (Directrice de thèse) Mme Sylvie BAUER , Professeur à l’Université Rennes-2 (Rapporteur) Mme Christine FROULA , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) Mme Michal GINSBURG , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) M. Jean-Paul ROCCHI , Professeur à l’Université Paris-Est (Examinateur) Mme Sophie VALLAS , Professeur à l’Université d’Aix-Marseille (Rapporteur) M. Samuel WEBER , Professeur à Northwestern University (Co-directeur de thèse) In memory of Matt Acknowledgements I wish I had a more gracious thank-you for: Mme Isabelle Alfandary , who, over the years has allowed me to experience untold academic privileges; whose constant and consistently nurturing presence, intellectual rigor, patience, enthusiasm and invaluable advice are the sine qua non of my growth and, as a consequence, of this work. M. Samuel Weber , whose intellectual generosity, patience and understanding are unparalleled, whose Paris Program in Critical Theory was critical in more ways than one, and without whose participation, the co-tutelle would have been impossible. -

'Little Terrors'

Don DeLillo’s Promiscuous Fictions: The Adulterous Triangle of Sex, Space, and Language Diana Marie Jenkins A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of English University of NSW, December 2005 This thesis is dedicated to the loving memory of a wonderful grandfather, and a beautiful niece. I wish they were here to see me finish what both saw me start. Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One 26 The Space of the Hotel/Motel Room Chapter Two 81 Described Space and Sexual Transgression Chapter Three 124 The Reciprocal Space of the Journey and the Image Chapter Four 171 The Space of the Secret Conclusion 232 Reference List 238 Abstract This thesis takes up J. G. Ballard’s contention, that ‘the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else,’ to show that Don DeLillo uses a particular sexual, cultural economy of adultery, understood in its many loaded cultural and literary contexts, as a model for semantic reproduction. I contend that DeLillo’s fiction evinces a promiscuous model of language that structurally reflects the myth of the adulterous triangle. The thesis makes a significant intervention into DeLillo scholarship by challenging Paul Maltby’s suggestion that DeLillo’s linguistic model is Romantic and pure. My analysis of the narrative operations of adultery in his work reveals the alternative promiscuous model. I discuss ten DeLillo novels and one play – Americana, Players, The Names, White Noise, Libra, Mao II, Underworld, the play Valparaiso, The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, and the pseudonymous Amazons – that feature adultery narratives. -

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity © Anna Khimasia, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privee, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this thesis. -

The Sublime in Don Delillo's Mao II

International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Online: 2015-03-23 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 50, pp 137-145 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.50.137 CC BY 4.0. Published by SciPress Ltd, Switzerland, 2015 The Sublime in Don DeLillo’s Mao II Niloufar Behrooz, Hossein Pirnajmuddin Department of English. University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran Email address: [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Don DeLillo; postmodernism; the sublime; technology; violence; spirituality ABSTRACT The world that DeLillo’s characters live in is often portrayed with an inherent complexity beyond our comprehension, which ultimately leads to a quality of woe and wonder which is characteristic of the concept of the sublime. The inexpressibility of the events that emerge in DeLillo’s fiction has reintroduced into it what Lyotard calls “the unpresentable in presentation itself” (PC 81), or to put it in Jameson’s words, the “postmodern sublime” (38). The sublime, however, appears in DeLillo’s fiction in several forms and it is the aim of this study to examine these various forms of sublimity. It is attempted to read DeLillo’s Mao II in the light of theories of the sublime, drawing on figures like Burke, Kant, Lyotard, Jameson and Zizek. In DeLillo’s novel, it is no longer the divine and magnificent in nature that leads to a simultaneous fear and fascination in the viewers, but the power of technology and sublime violence among other things. The sublime in DeLillo takes many different names, ranging from the technological and violent to the hollow and nostalgic, but that does not undermine its essential effect of wonder; it just means that the sublime, like any other phenomenon, has adapted itself to the new conditions of representation. -

An Examination of Conspiracy and Terror in the Works of Don Delillo

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Spring 5-7-2011 For the Future: An Examination of Conspiracy and Terror in the Works of Don Delillo Ashleigh Whelan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Whelan, Ashleigh, "For the Future: An Examination of Conspiracy and Terror in the Works of Don Delillo." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/104 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOR THE FUTURE: AN EXAMINATION OF CONSPIRACY AND TERROR IN THE WORKS OF DON DELILLO by ASHLEIGH WHELAN Under the Direction of Dr. Christopher Kocela ABSTRACT This thesis is divided into two chapters, the first being an examination of conspiracy and paranoia in Libra, while the second focuses on the relationship between art and terror in Mao II, “In the Ruins of the Future,” Falling Man, and Point Omega. The study traces how DeLillo’s works have evolved over the years, focusing on the creation of counternarratives. Readers are given a glimpse of American culture and shown the power of narrative, ultimately shedding light on the future of our collective consciousness. INDEX -

Cultivated Tragedy: Art, Aesthetics, and Terrorism in Don Delillo's Falling

Bartlett 1 CULTIVATED TRAGEDY: ART, AESTHETICS, AND TERRORISM IN DON DELILLO’S FALLING MAN By Jen Bartlett “We are not free and the sky can still fall on our heads. Above all, theatre is meant to teach us this.” (The Theatre and Its Double, 60) On September 11th 2001, the sky did just that and the photogenic skyline of New York City came tumbling down. In a controversial New York Times article, Karl-Heinz Stockhausen termed these events “the greatest work of art in the whole cosmos” and although this outraged the nation at the time and was quickly suppressed, it does not make the theoretical approach any less valid. Don DeLillo’s works and his ongoing exploration of authorship and terrorism are an encapsulation of Frank Lentricchia and Jody McAuliffe’s observation that “the impulse to create transgressive art and the impulse to commit violence lie perilously close to each other.” Exponents of the 'Gesamtkunstwerk' or 'total art work' advocated an attack on all senses and emotions. Wagner and Runge, amongst others, believed that if one unified the visual, aural and textual arts into one completely integrated whole, the effect on the audience would be of such power that great personal, and consequently social, change or revolution could be effected (Grey 1995). Artaud developed these principles further in his 'Theatre of Cruelty' by moving from representations of an experience to providing the audience with the actual experience. Watching his play Plague, Anaïs Nin found that instead of “an objective conference on the theater [sic] and the plague” the audience members were forced to undergo the experience of “the plague itself” (192).